Sudan Case Study 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sudan's Spreading Conflict (II): War in Blue Nile

Sudan’s Spreading Conflict (II): War in Blue Nile Africa Report N°204 | 18 June 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Sudan in Miniature ....................................................................................................... 3 A. Old-Timers Versus Newcomers ................................................................................. 3 B. A History of Land Grabbing and Exploitation .......................................................... 5 C. Twenty Years of War in Blue Nile (1985-2005) ........................................................ 7 III. Failure of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement ............................................................. 9 A. The Only State with an Opposition Governor (2007-2011) ...................................... 9 B. The 2010 Disputed Elections ..................................................................................... 9 C. Failed Popular Consultations ................................................................................... -

The Fall of Al-Bashir: Mapping Contestation Forces in Sudan

Bawader, 12th April 2019 The Fall of al-Bashir: Mapping Contestation Forces in Sudan → Magdi El-Gizouli Protests in Khartoum calling for regime change © EPA-EFE/STR What is the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA) anyway, perplexed commentators and news anchors on Sudan’s government-aligned television channels asked repetitively as if bound by a spell? An anchor on the BBC Arabic Channel described the SPA as “mysterious” and “bewildering”. Most were asking about the apparently unfathomable body that has taken the Sudanese political scene by surprise since December 2018 when the ongoing wave of popular protests against President Omar al-Bashir’s 30-year authoritarian rule began. The initial spark of protests came from Atbara, a dusty town pressed between the Nile and the desert some 350km north of the capital, Khartoum. A crowd of school pupils, market labourers and university students raged against the government in response to an abrupt tripling of the price of bread as a result of the government’s removal of wheat subsidies. Protestors in several towns across the country set fire to the headquarters of the ruling National Congress Party (NCP) and stormed local government offices and Zakat Chamber1 storehouses taking food items in a show of popular sovereignty. Territorial separation and economic freefall Since the independence of South Sudan in 2011, Sudan’s economy has been experiencing a freefall as the bulk of its oil and government revenues withered away almost overnight. Currency depreciation, hyperinflation and dwindling foreign currency reserves coupled with the rise in the prices of good and a banking crisis with severe cash supply shortages, have all contributed to the economic crisis. -

How to Implement Sudan's New Peace Agreement

The Rebels Come to Khartoum: How to Implement Sudan’s New Peace Agreement Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°168 Khartoum/Nairobi/Brussels, 23 February 2021 What’s new? A peace agreement signed on 3 October 2020 paves the way for armed and unarmed opposition groups in Sudan to join the transitional government, dra- matically expanding representation of the country’s peripheries during the interim period before elections. The two most powerful rebel movements remain outside the accord, however. Why does it matter? Clinching the agreement was necessary for the country’s transition but implementation poses challenges. The agreement risks bloating the military and sets up a prospective political alliance between the rebels and Sudanese security forces, which could further sideline the government’s civilian cabinet and threaten to bury its reform agenda. What should be done? The interim government should negotiate with holdout rebels to bring them into the transition. Sudan’s international partners should press for security sector reform that decreases the size and political dominance of a newly expanded military while funding and supporting the authorities’ spending commit- ments in the peripheries. I. Overview Sudan’s October 2020 peace agreement, involving the interim government and rebel movements in Darfur and the Two Areas, among others, is an important step in the country’s transition after the ouster of former President Omar al-Bashir. The deal allows for representatives from armed groups in the country’s peripheries to take government posts and for significant public money to go to these areas. It is a way to rebalance the Nile Valley elites’ decades-long domination of Sudan’s political system. -

Sudan Opposition to the Government, Including

Country Policy and Information Note Sudan: Opposition to the government, including sur place activity Version 2.0 November 2018 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis of COI; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Asessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

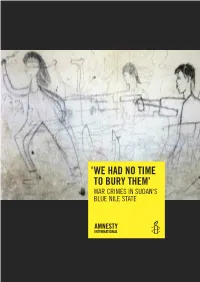

We Had No Time to Bury Them' '

‘we had no time to bury them’ WAR CRImes In sudAn’s Blue nIle stAte amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2013 by amnesty international ltd Peter benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0dw united Kingdom © amnesty international 2013 index: aFr 54/011/2013 english original language: english Printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united Kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: a child’s drawing found in a bombed and abandoned school in blue nile state, sudan, april 2013. many children have been among those killed and injured in recent attacks by sudanese military forces on civilian villages in the state. -

Sudan's Bloody Periphery

VIKTOR PESENTI VIKTOR Sudan’s Bloody Periphery The Toll on Civilians from the War in Blue Nile State By Matthew LeRiche WWW.ENOUGHPROJECT.ORG Sudan’s Bloody Periphery The Toll on Civilians from the War in Blue Nile State By Matthew LeRiche COVER PHOTO Civilians in Sudan’s Blue Nile state flee their homes and go to refugee camps. VIKTOR PESENTI Introduction Since September 2011, the Sudanese government’s campaign of repression against opposition groups in its Blue Nile state has developed into an armed conflict between the Sudan Armed Forces, or SAF, and a coalition of rebel groups, the Sudan Revolutionary Forces, or SRF. This war has exacted a severe humanitarian toll on Blue Nile’s civilian population, due in large part to the SAF’s indiscriminate aerial bombing of civilian areas, a ground offensive that does not distinguish between civilian and military targets, and repression of groups in government-controlled areas suspected of supporting the rebels.1 In early 2013, the SAF and associated armed groups launched attacks with increasing frequency in areas of Blue Nile state. For most of 2012, a consistent aerial-bombardment campaign terrorized the state’s popu- lation, causing the majority to flee to refugee camps in Ethiopia, South Sudan, and informal settlements for internally displaced persons, or IDPs. SAF ground attacks during the dry season in early 2013—while maintaining aerial bombing—marked a shift in tactics, causing even more civilians to flee the violence. This report is based on visits to the front lines in central Blue Nile in late 2012 and early 2013, and details the current situation of the armed conflict there and its effect on the civilian population. -

Sudan's Spreading Conflict (II): War in Blue Nile

Sudan’s Spreading Conflict (II): War in Blue Nile Africa Report N°204 | 18 June 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Sudan in Miniature ....................................................................................................... 3 A. Old-Timers Versus Newcomers ................................................................................. 3 B. A History of Land Grabbing and Exploitation .......................................................... 6 C. Twenty Years of War in Blue Nile (1985-2005) ........................................................ 7 III. Failure of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement ............................................................. 10 A. The Only State with an Opposition Governor (2007-2011) ...................................... 10 B. The 2010 Disputed Elections ..................................................................................... 10 C. Failed Popular Consultations ................................................................................... -

SUDAN Humanitarian Situation Report

d1744 and 1661: ©UN ICEF Sudan/2017/D ismasJuniorBIRARONDERWA PlPl SUDAN Humanitarian Situation Report First Quarter 2020 A girl child shows her classmate how to properly wash hands using soap and water at Ban Jadid Primary School in El-Fasher, North Darfur, Credit: © UNICEF/UNI233846/Noorani SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 5.39 million children among • Inter-tribal conflict in West Darfur during the last days of 2019 displaced around 40,000 people into El-Geneina town. UNICEF mobilized an intersec- 9.3 million people who need toral response that included emergency latrines, education supplies for Humanitarian Assistance 3,250 children, safe access to water for 31,000 people, 760 baby blankets, (Source: Sudan Humanitarian Needs Overview 20201) measles immunization for 1,298 babies, four temporary primary health cen- tres, training for 70 government staff on running Child-Friendly Spaces and 1 million2 children among providing psychosocial support to IDP children. • COVID-19 arose as an imminent humanitarian threat to Sudan. During Feb- 1.8 million internally displaced ruary and March, UNICEF determined and initiated its response, aligned into (Source: Sudan Humanitarian Needs Overview 2020) the Transitional Government and wider UN response strategy. UNICEF has 425,600 children3 among taken the national lead on Risk Communication and Community Education, country level coordination, provision of WASH services to critical facilities, 818,462 South Sudanese refugees and provision of Personal Protective Equipment. • UNICEF provided support through NCCW to reunify 2000 Khartoum based UNICEF Appeal 2020 Khalwa students with their families in other states following the implemen- US$ 147.11 million tation of COVID-19 movement restrictions. -

Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF)

Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF) Origins/composition On 13 November 2011, following lengthy negotiations, four Darfurian rebel groups— the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), and the Sudan Liberation Army factions of Minni Minawi (SLA-MM) and Abdul Wahid (SLA-AW)—joined together in an alliance with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N) to form the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF). The SRF has the potential to put an end to the fragmentation of rebel groups by uniting them under Abdul Aziz al Hilu. It also challenges the GoS’s strategy of isolation by introducing a national agenda, including regime change. It provides the Darfur groups with access to the Nuba Mountains for rear bases for possible attacks on Khartoum. The alliance also improves Darfurian groups’ links with Juba through the SPLM-N. 1 But for the alliance to be successful, it must overcome the persistent power struggles and philosophical differences between the Darfur factions, as well as the challenges of increased military cooperation. Leadership The Leadership Council of the SRF was announced on 20 February 2012. The alliance is dominated at the top tier by the SPLM-N: • Malik Agar, chairman • Abdel Aziz al Hilu, commander in chief of the joint military forces • Yasser Arman, secretary for external affairs The three Darfur rebel groups share vice-chairman positions with separate portfolios: • Abdel Wahid al Nur, vice-chairmen of political affairs • Minni Minnawi, vice-chairman of finance • Jibril Ibrahim, vice-chairman of external affairs In addition: • Buthaina Ibrahim Dinar (SPLM-N), Elryaih Mahmoud (SLM-MM), Ahmed Adam Bakheit (JEM), and Mustafa Sharif Mohamed (SLM-AW) serve in the political affairs office under Abdel Wahid. -

Why Sudan's Popular Consultation Matters

UNIteD StAteS INStItUte of Peace www.usip.org SPeCIAL RePoRt 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Jason Gluck This report examines Sudan’s popular consultation, an ongoing process whereby the people of the Sudanese states of Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile will democratically and popularly assess the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement and determine whether it satisfactorily reflects the aspirations of the people. Why Sudan’s Popular If not, the two states will negotiate with the government of Sudan to remedy any defects in the agreement in order to reach a final settlement of the decades-long Sudanese civil war. This report seeks to explain what popular consultation is, Consultation Matters how it is likely to unfold, what the metrics are for measuring success, and what roles the international community might play. In addition, the report describes how a successful process Summary could transform Sudanese politics and governance, and how a neglected or mismanaged process could destabilize not • Largely unnoticed outside the region, the Sudanese states of Southern Kordofan and Blue just Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile, but all Sudan. In other Nile have begun the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA)–mandated process of popular words, it explains why popular consultation matters. consultation, which permits Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile to either adopt the CPA as the Jason Gluck is a senior rule of law adviser in USIP’s Rule of Law final settlement between the two states and the Government of Sudan (GoS) or renegotiate Center of Innovation. -

Conflict in the Two Areas Describing Events Through 29 January 2015

Conflict in the Two Areas Describing events through 29 January 2015 The conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile, the so-called Two Areas, between the Government of Sudan (GoS) and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army- North (SPLM/A-N), has entered its fourth year. While the conflict has reached a military stalemate, all efforts to bring about a negotiated settlement to the conflicts have failed, and a dry season offensive has already begun in South Kordofan and to a lesser extent in Blue Nile. The seventh round of African Union High Implementation Panel (AUHIP)-sponsored talks between the rebels and the GoS began on 12 November in Addis Ababa, but the ‘one process, two tracks’ (Darfur, Two Areas) negotiations ended on 8 December without major progress. While negotiations were officially ongoing, on 1 December fighting erupted in South Kordofan, followed by heavy aerial bombardments. In January 2015, the Sudan Humanitarian and Aid Commission said some 145,000 people are expected to flee from SPLA-N areas in South Kordofan into government areas ahead of an expected GoS offensive. According to the SPLM/A-N, almost one million people in the Two Areas live under dire humanitarian conditions. On 23 November, peace negotiations between the government and the two main Sudanese rebel factions—the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) and the Sudan Liberation Army led by Minni Minnawi (SLA-MM)—started in Addis Ababa (the other armed group in the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF), SLA-Abdul Wahid al- Nur (SLA-AW) did not participate). The two-track approach is supported by the international community and endorsed in the African Union Peace and Security Council Communiqué 456 of 12 September 2014. -

A View from Blue Nile

A View from Blue Nile November 29, 2011 By Nenad Marinkovic Blue Nile, Sudan - Enough has recently documented that Sudanese military forces in Blue Nile state have engaged in the killing and raping of civilians, resulting in tens of thousands of refugees and displaced persons fleeing for safety in neighboring Ethiopia and South Sudan, and within Blue Nile. The civilian toll from an indiscriminate aerial bombardment campaign is rising. In addition to these devastating effects on civilians, Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, in September, used the violence in Blue Nile as a pretext to declare a state of emergency in the state and remove its democratically elected governor, Malik Agar, forcing him into hiding. On a trip to a location near Kurmuk in Blue Nile close to the Ethiopian border, Enough Project staff spoke to Agar about the current situation and his aspirations for Sudan’s future. ______________________________________ On the evening of September 1, 2011, the Sudan Armed Forces, or SAF, attacked Damazin, the capital of Blue Nile state. One of the first targets of this operation was the residence of Malik Agar, the elected governor of the state and the chairman of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement- North, or SPLM-N. As a result, Agar was ousted from his governorship and the Sudan government appointed a military administration in his place. He fled Damazin with forces of the SPLM-N’s military wing, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North, or SPLA-N, to an area close to the town of Kurmuk, near the Ethiopian border. The fighting in Blue Nile has, from the start, followed the pattern of previous clashes in South Kordofan, using frequent aerial bombardments that have repeatedly fallen on the civilian population.