Chapter Four: the BBC Regime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DJ Tiiny, Capital XTRA, Various Dates, 1900

v Issue 424 12 April 2021 DJ Tiiny Type of case Broadcast Standards Outcome Resolved Service Capital XTRA Date & time Various dates, 19:00 Category Commercial communications on radio Summary The presenter played music tracks in return for payment. The Broadcasting Code prohibits any payment that may influence the selection or rotation of music for broadcast. In view of the action taken by the Licensee when it became aware of the presenter’s actions, we considered the matter resolved. Introduction Capital XTRA is a local radio station providing an urban contemporary black music service for African and Afro-Caribbean communities in North London. It is simulcast nationally on DAB, satellite and cable services. Capital XTRA’s licence is held by Capital Xtra Limited, which is owned by Global Media & Entertainment Limited (“Global”). DJ Tiiny was a show broadcast weekly on Friday evenings. A complainant alleged that the presenter played some artists’ music tracks in return for payment. Global contacted Ofcom and confirmed the allegation, saying that it had been alerted to the matter on 27 January 2021 and that the presenter’s contract of employment had been terminated the following day. Ofcom considered the matter raised potential issues under the following Code rule: Rule 10.5: “No commercial arrangement that involves payment, or the provision of some other valuable consideration, to the broadcaster may influence the selection or rotation of music for broadcast”. Issue 424 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 12 April 2021 1 We therefore requested comments from Global on how programmes in which the presenter had played music tracks in return for payment complied with this rule. -

Introduction to Ascential Our Investment Case

INTRODUCTION TO ASCENTIAL OUR INVESTMENT CASE Clear long-term vision. Helping leading global brands connect with their customers in a data-driven world. Structural growth. Demand for information, data & analytics driven by growth of digital commerce. Market leaders. We are leaders, with a unique blend of specialisms, in the high growth areas in which we operate. Robust business model. High recurring and repeat revenue, with more than 50% revenues from digital subscription and platforms, across diverse global customer base. Attractive financial profile. Track record of high single digit revenue growth, strong margins and cash generation, supported by sound capital allocation. Introduction to Ascential 2 OUR CUSTOMER PROPOSITION Our information products and platforms support our customers to do three simple things… CREATE THE RIGHT MAXIMISE THE OPTIMISE DIGITAL PRODUCTS BRAND MARKETING COMMERCE IMPACT Know which products Know how to get Know how to execute the consumer wants maximum creativity with with excellence on the tomorrow. optimised media. winning platforms. 1. 2. 3. Introduction to Ascential 3 SEGMENTAL OVERVIEW –2019 Segment Revenue % Revenue1 Growth1 EBITDA2 Margin Business Model Advisory 10% Digital Subscriptions Product £86m 21% +8% £36m 42% & Platforms 90% Design Digital Subscriptions Advisory & Platforms 11% Marketing £136m 32% +9% £51m 37% 37% Events 52% Advisory 6% Digital Subscriptions & Sales - Platforms 94% Digital £90m 22% +21% £13m 15% Commerce Sales - Digital Subscriptions & Events Platforms 4% Non Digital £68m 16% -

BT Group (WACC Response, Oxera Report)

Quantifying the relative risk differences between FTTP and FTTC Prepared for BT Group plc 14 January 2021 Final: public www.oxera.com Final: public Quantifying the relative risk differences between FTTP and FTTC Oxera Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Summary of main findings 2 1.2 Structure of the report 3 2 Ofcom’s proposals on WACC and relative systematic risk differentials 4 2.1 Theoretical support for differences in systematic risk 4 2.2 Overview of Ofcom’s analysis and proposals 7 3 Income elasticities and asset betas 10 3.1 BT consumer experiment and income elasticities 10 3.2 Calculating the relationship between income elasticity and asset beta 12 3.3 Predicting the asset beta wedge between FTTC and FTTP 13 3.4 Conclusions 15 4 Conclusion 16 A1 Details of consumer choice experiment 17 Boxes, figures and tables Box 2.1 Illustration of the relationship between operating leverage and systematic risk 6 Table 2.1 Summary of Ofcom’s proposals 9 Box 3.1 The field experiment commissioned by BT 10 Table 3.1 FTTP regression coefficients 11 Table 3.2 FTTC regression coefficients 11 Table 3.3 Projection of income elasticity for copper 12 Table 3.4 US panel regression’s results 13 Table 3.5 Estimated asset beta wedge due to income elasticity 14 Table A1.1 FTTC’s products summary statistics 17 Table A1.2 FTTP’s products summary statistics 17 Table A1.3 Respondents’ income in FTTC survey 18 Table A1.4 Respondents’ income in FTTP survey 18 Final: public Quantifying the relative risk differences between FTTP and FTTC 2 Oxera 1 Introduction Oxera has -

Capital Birmingham Should Not Be Allowed to Make the Changes to The

Spence, Mr Consultation question: Should regional radio station Capital FM (Birmingham) be permitted to make the changes to its Character of Service as proposed with particular regard to the statutory criteria as set out in the summary? (The Broadcasting Act 1990 Section 106 (1A) (b) and (d) relating to Format changes). Capital Birmingham should not be allowed to make the changes to the Character of Service as this would essentially change the station from am urban/black music station to a hit music station format which can potentially stop playing urban music if they wanted to if in the future it becomes less mainstream. The format change represents a real danger to the radio landscape in Birmingham as it can so significantly reduce the choice of music available in the area over time. It will make the station sound too similar to it's main competitors in the area on FM. I am not happy with the decision in particular to remove the commitment to listeners of African or Afro-Caribbean origin in terms of content and music. I do not believe the music output of Capital Birmingham should be allowed to be aligned to that of Yorkshire or London without a readvertisement of the license as the change requested is far too significant. I believe that the format must retain the words 'URBAN CONTEMPORARY BLACK MUSIC' and 'REGGAE, RnB AND HIP HOP' in order to be an acceptable request. The new requested format is already provided in much better quality by BBC Radio 1. I am not happy with the way the station has been allowed to gradually change from Choice FM in the mid 90s to the present day Capital FM with such a dramatic change in music output despite only slight changes to the official OFCOM agreed station format, while Choice London and Capital FM co-exist in London providing 2 very different sounding services. -

Ofcom Audio Survey 2021: Questionnaire

Survey name: Ofcom Audio Survey 2021 Timings: 3-7 March 2021 Methodology: Online survey We are conducting research on behalf of the UK's communications regulator Ofcom, who are looking to understand use of and attitudes towards different types of radio and audio services. ASK ALL 1. How often, if at all, do you do any of the following? GRID ROWS – RANDOMISE ORDER 1. A. Listen to radio (at the time of broadcast: not catch-up/podcast) 2. B. Listen to catch-up radio 3. C. Listen to music online 4. D. Listen to music stored or downloaded on a device 5. E. Listen to personal music collection (e.g. CDs, vinyls) 6. F. Listen to podcasts 7. G. Listen to audiobooks (digital/online and physical) 8. H. Use music videos as background listening (i.e. music video channels or sites such as YouTube or MTV) 9. GRID COLUMNS – SINGLE CODE 1. Several times a day 2. About once a day 3. Several times a week 4. About once a week 5. Several times a month 6. About once a month 7. Less often 8. Never ASK ALL (BACK FILTER ANYONE WHO LISTS A STATION HERE BUT DID NOT CODE ‘A RADIO STATION’ IN Q1) 2. Which, if any, of these radio stations have you listened to in the last 7 days? MULTICODE BBC Radio 1 BBC Radio 2 BBC Radio 3 BBC Radio 4 BBC Radio 5 live BBC 6 Music BBC Asian Network BBC Radio 1Xtra BBC Radio 4 Extra BBC Radio 5 live sports extra BBC World Service BBC radio for your nation / region (e.g. -

Industry Outlook

Industry outlook 39 Resilience, recovery, acceleration by Sir Martin Sorrell S4Capital Annual Report and Accounts 2020 37 Industry outlook 38 S4Capital Annual Report and Accounts 2020 2 Digital adoption has accelerated On the whole, covid-19 didn’t create Resilience, new trends; it accelerated existing ones. Digital adoption was stepped up by consumers. During the early days of the pandemic some 30% of US households recover y, went online for groceries for the first time; online education took off; and streaming went through the roof. Disney+ was targeting 70-80 million consumers by 2024, but it acceleration rapidly went to 100 million (and forecasts 240 million for 2024) and found itself competing with Netflix. By Sir Martin Sorrell Alan Jope tells the story that when he was running Unilever in China during the SARS outbreak, there was this massive surge among You have to find the silver linings Chinese online; in 2020 we saw a similarity The nature of our client base contributed when Nike gave away their fitness app to significantly to our resilience during the the Chinese consumer for free – it sparked a pandemic. Technology and healthcare significant uptick in online activity. together account for more than half of our The tech giants, whether Google, Facebook client spend and those were sectors that and Amazon, or Alibaba, Tencent and Tik- didn’t stop their marketing and in some Tok are all set to emerge from the pandemic cases reinforced it. Our people played a huge stronger than ever. Digital adoption has part; they are entrepreneurial and can turn also been stepped up at enterprise level. -

Public Investment Memorandum

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA PUBLIC SCHOOL EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT SYSTEM Public Investment Memorandum LBC - PSERS Credit Fund, L.P. High Yield Commitment James F. Del Gaudio Senior Investment Professional November 20, 2015 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA PUBLIC SCHOOL EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT SYSTEM Recommendation: Staff, together with Portfolio Advisors, recommends the Board commit up to $350 million to LBC - PSERS Credit Fund, L.P. (the “Fund”). The Fund will be structured as a separately managed account and is being raised in conjunction with LBC Credit Partners IV, L.P. (“Fund IV”), a commingled fund. The Fund will continue the investment strategy of LBC Credit Management, L.P. (“LBC” or the “Firm”). It is anticipated that the Fund will co-invest with Fund IV and its future successor funds on a pro-rata basis. Firm Overview: LBC was co-founded in 2005 by John Brignola, Christopher Calabrese, Nathaniel Cohen and Ira M. Lubert to provide financing solutions to North American middle market companies. The Firm is headquartered in Philadelphia, and employs 21 investment professionals. Today, LBC manages over $1.75 billion of capital commitments and has invested ~$3.5 billion (including leverage) across three investments funds: Commitments Fund Vintage ($mm) LBC Credit Partners, L.P. (“Fund I”) 2005 $300 LBC Credit Partners II, L.P. (“Fund II”) 2008 $642 LBC Credit Partners III, L.P. (“Fund III”) 2013 $839 Investment Strategy: The Fund will originate and manage a diversified portfolio of secured, middle market loans to North American borrowers. LBC defines middle market companies as those with revenues of typically less than $750 million and EBITDA of $5 million to $50 million. -

New York City, the Podcasting Capital

NEW YORK CITY, THE PODCASTING CAPITAL TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 INTRODUCTION 9 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PODCAST 11 NATIONAL LANDSCAPE OF PODCASTING 12 PODCAST GROWTH 14 ADVERTISING 15 THE IMPACT OF PODCAST ADVERTISING 16 ADVERTISING MODELS IN PODCASTING 17 PRICING MODEL 18 ADVERTISING TECHNOLOGY 19 NEW YORK CITY, THE CAPITAL OF PODCASTING 20 NEW YORK CITY’S PODCAST NETWORKS 22 NEW YORK CITY PODCAST INDUSTRY GROWTH 23 THE NEW YORK CITY PODCAST COMMUNITY 24 INCREASING DIVERSITY IN NEW YORK CITY PODCASTING 26 TECHNOLOGY 28 THE FUTURE OF PODCASTING 30 CONCLUSION 31 PODCASTERS’ FAVORITE PODCASTS 32 REFERENCES 33 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Podcasts are the newest form of the oldest entertainment medium: storytelling. Today’s podcasts are a major forum for the exchange of ideas, and many are calling this time the “renaissance of podcasting.” Born out of the marriage of public radio and the internet, podcasting has adapted to follow modern consumption patterns and the high demand for readily accessible entertainment. Podcasts are making New York City their home. The density of advertising firms, technology companies, major brands, digital media organizations, and talent has established New York City as the epicenter of the burgeoning podcast industry. New York City is home to the fastest growing podcast startups, which have doubled, tripled, and quadrupled their size in the past several years – in employment, office space, and listenership. New York City’s podcast networks are growing rapidly, reflecting the huge national audience of 42 million weekly listeners. Employment at the top New York City podcast networks has increased over the past several years, from about 450 people in 2015 to about 600 people in early 2017. -

Bauer Media Group Phase 1 Decision

Completed acquisitions by Bauer Media Group of certain businesses of Celador Entertainment Limited, Lincs FM Group Limited and Wireless Group Limited, as well as the entire business of UKRD Group Limited Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition ME/6809/19; ME/6810/19; ME/6811/19; and ME/6812/19 The CMA’s decision on reference under section 22(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 given on 24 July 2019. Full text of the decision published on 30 August 2019. Please note that [] indicates figures or text which have been deleted or replaced in ranges at the request of the parties or third parties for reasons of commercial confidentiality. SUMMARY 1. Between 31 January 2019 and 31 March 2019 Heinrich Bauer Verlag KG (trading as Bauer Media Group (Bauer)), through subsidiaries, bought: (a) From Celador Entertainment Limited (Celador), 16 local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences (the Celador Acquisition); (b) From Lincs FM Group Limited (Lincs), nine local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences, a [] interest in an additional local radio station and associated licences, and interests in the Lincolnshire [] and Suffolk [] digital multiplexes (the Lincs Acquisition); (c) From The Wireless Group Limited (Wireless), 12 local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences, as well as digital multiplexes in Stoke, Swansea and Bradford (the Wireless Acquisition); and (d) The entire issued share capital of UKRD Group Limited (UKRD) and all of UKRD’s assets, namely ten local radio stations and the associated local 1 FM radio licences, interests in local multiplexes, and UKRD’s 50% interest in First Radio Sales (FRS) (the UKRD Acquisition). -

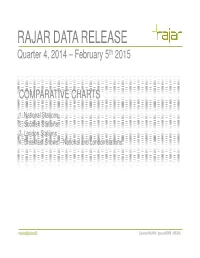

Comparative Data Chartspdf

RAJAR DATA RELEASE Quarter 4, 2014 – February 5 th 2015 COMPARATIVE CHARTS 1. National Stations 2. Scottish Stations 3. London Stations 4. Breakfast Shows – National and London stations Source RAJAR / Ipsos MORI / RSMB RAJAR DATA RELEASE Quarter 4, 2014 – February 5 th 2015 NATIONAL STATIONS SAMPLE SIZE: TERMS WEEKLY The number in thousands of the UK/area adult population w ho listen to a station for at least 5 minutes in the Survey period - Q4 2014 REACH: course of an average w eek. SHARE OF Code Q (Quarter): 25,124 Adults 15+ The percentage of total listening time accounted for by a station in the area (TSA) in an average w eek. LISTENING: TOTAL Code H (Half year): 49,369 Adults 15+ The overall number of hours of adult listening to a station in the UK/area in an average w eek. HOURS: TOTAL HOURS (in thousands): ALL BBC Q4 13 568433 Q3 14 545934 Q4 14 536759 TOTAL HOURS (in thousands): ALL COMMERCIAL Q4 13 433520 Q3 14 445056 Q4 14 450398 STATIONS SURVEY REACH REACH REACH % CHANGE % CHANGE SHARE SHARE SHARE PERIOD '000 '000 '000 REACH Y/Y REACH Q/Q % % % Q4 13 Q3 14 Q4 14 Q4 14 vs. Q4 13 Q4 14 vs. Q3 14 Q4 13 Q3 14 Q4 14 ALL RADIO Q 48375 47614 47851 -1.1% 0.5% 100.0 100.0 100.0 ALL BBC Q 36219 34845 34798 -3.9% -0.1% 55.2 53.6 52.8 15-44 Q 15948 15116 14840 -6.9% -1.8% 42.2 41.7 38.6 45+ Q 20271 19729 19958 -1.5% 1.2% 63.8 61.3 61.7 ALL BBC NETWORK RADIO Q 33126 31686 31798 -4.0% 0.4% 46.8 45.7 45.3 BBC RADIO 1 Q 10969 10550 10433 -4.9% -1.1% 6.9 6.9 6.6 BBC RADIO 2 Q 15513 15014 15283 -1.5% 1.8% 17.6 17.0 17.8 BBC RADIO 3 Q 1992 1912 2030 1.9% 6.2% 1.1 1.1 1.1 BBC RADIO 4 Q 11205 10621 10760 -4.0% 1.3% 12.5 11.9 11.9 BBC RADIO 4 (including 4 EXTRA) Q 11494 10916 11033 -4.0% 1.1% 13.5 12.8 12.9 BBC RADIO 4 EXTRA Q 1646 1629 1721 4.6% 5.6% 1.0 0.9 1.1 BBC RADIO 5 LIVE Q 6285 5809 5610 -10.7% -3.4% 4.2 3.8 3.5 BBC RADIO 5 LIVE (inc. -

In Strictest Confidence

In strictest confidence BT‘s response to Ofcom‘s cost of capital proposals contained in recent Charge Control consultations April 2011 NON-CONFIDENTIAL VERSION BT welcomes comments on the content of this document Comments should be addressed to: Felipe Florez Duncan ([email protected]) or James Tickel ([email protected]) BT Group Regulatory Affairs, BT Centre, London, EC1A 7AJ BT‘s response to Ofcom‘s cost of capital proposal Contents Page 1 Introduction and summary of BT’s position 3 2 Our detailed views on individual WACC parameters 6 2.1 Nominal Risk-free rate 6 2.1.1 Real risk-free rate 6 2.1.2 Inflation 8 2.1.3 Conclusion on the nominal risk-free rate 8 2.2 Equity risk premium (ERP) 9 2.3 Equity beta, asset beta and gearing 9 2.4 Debt premium and the overall cost of debt 14 3 An appropriate WACC range for 2013/14 16 4 Response to specific consultation questions 18 Page 2 of 19 BT‘s response to Ofcom‘s cost of capital proposal 1 Introduction and summary of BT‘s position Ofcom‘s consultation on the charge controls to apply to BT in the provision of Wholesale Broadband Access services in geographic ―market 1‖ published in January 2011 proposed – among other things – to reduce BT Group‘s pre-tax nominal WACC by 170bp (from 10.6% to 8.9%). The proposals for the separate disaggregated WACCs for ―Openreach‖ and ―Rest of BT‖ reflected similar reductions. These same proposals were then set out in the separate consultations published at the end of March/start of April on the charge controls to be applied to BT‘s provision of LLU, WLR and ISDN30 services. -

Oxford Street to Launch Brand New Christmas Lights Scheme to Celebrate 60 Years of Lighting up the Capital

OXFORD STREET TO LAUNCH BRAND NEW CHRISTMAS LIGHTS SCHEME TO CELEBRATE 60 YEARS OF LIGHTING UP THE CAPITAL • Saving the best until last, Oxford Street will kick off Christmas on Thursday 21 November as it illuminates the West End • Oxford Street to launch a brand new digital lighting scheme with 27 LED light curtains that will be draped over Oxford Street this Christmas displaying curated, dynamic content while providing energy savings of up to 90% against traditional lighting • Oxford Street has partnered with Capital XTRA, the UK’s leading hip-hop, grime and R&B station, to bring some of the best homegrown talent to the street for the switch-on evening Thursday 21 November will see Oxford Street, the UK’s most iconic shopping street, revolutionising 60 years of magical Christmas switch-ons as it reveals a brand new digital lighting scheme. With anticipation higher than ever before, visitors from around the globe are expected in their thousands to be the first to snap and share this brand new Christmas lighting experience, ensuring that once again, the world leading destination is first in mind for all things festive. As traditional static displays illuminate town centres up and down the country from early November, this year, Oxford Street will save the best until last as it unveils an innovative, brand new scheme featuring 27 spectacular LED light curtains draped over the length of the street, made up of 220,000 sparkling lights. Not only visually compelling, the new lighting scheme utilises the latest in progressive LED technology which provides energy savings of up to 90% against conventional lighting.