GWAS Meta-Analysis Reveals Novel Loci and Genetic Correlates for General Cognitive Function: a Report from the COGENT Consortium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hearing Aging Is 14.1±0.4% GWAS-Heritable

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.05.21260048; this version posted July 7, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC 4.0 International license . Predicting age from hearing test results with machine learning reveals the genetic and environmental factors underlying accelerated auditory aging Alan Le Goallec1,2+, Samuel Diai1+, Théo Vincent1, Chirag J. Patel1* 1Department of Biomedical Informatics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, 02115, USA 2Department of Systems, Synthetic and Quantitative Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 02118, USA +Co-first authors *Corresponding author Contact information: Chirag J Patel [email protected] Abstract With the aging of the world population, age-related hearing loss (presbycusis) and other hearing disorders such as tinnitus become more prevalent, leading to reduced quality of life and social isolation. Unveiling the genetic and environmental factors leading to age-related auditory disorders could suggest lifestyle and therapeutic interventions to slow auditory aging. In the following, we built the first machine learning-based hearing age predictor by training models to predict chronological age from hearing test results (root mean squared error=7.10±0.07 years; R-Squared=31.4±0.8%). We defined hearing age as the prediction outputted by the model on unseen samples, and accelerated auditory aging as the difference between a participant’s hearing age and age. We then performed a genome wide association study [GWAS] and found that accelerated hearing aging is 14.1±0.4% GWAS-heritable. -

Y-Chromosome Short Tandem Repeat, Typing Technology, Locus Information and Allele Frequency in Different Population: a Review

Vol. 14(27), pp. 2175-2178, 8 July, 2015 DOI:10.5897/AJB2015.14457 Article Number: 2E48C3F54052 ISSN 1684-5315 African Journal of Biotechnology Copyright © 2015 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB Review Y-Chromosome short tandem repeat, typing technology, locus information and allele frequency in different population: A review Muhanned Abdulhasan Kareem1, Ameera Omran Hussein2 and Imad Hadi Hameed2* 1Babylon University, Centre of Environmental Research, Hilla City, Iraq. 2Department of Molecular Biology, Babylon University, Hilla City, Iraq. Received 29 January, 2015; Accepted 29 June, 2015 Chromosome Y microsatellites seem to be ideal markers to delineate differences between human populations. They are transmitted in uniparental and they are very sensitive for genetic drift. This review will highlight the importance of the Y- Chromosome as a tool for tracing human evolution and describes some details of Y-chromosomal short tandem repeat (STR) analysis. Among them are: microsatellites, amplification using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of STRs, separation and detection and advantages of X-chromosomal microsatellites. Key words: Forensic, population, review, STR, Y- chromosome. INTRODUCTION Microsatellites are DNA regions with repeat units that are microsatellite, but repeats of five (penta-) or six (hexa-) 2 to 7 bp in length or most generally short tandem nucleotides are usually classified as microsatellites as repeats (STRs) or simple sequence repeats (SSRs) well. DNA can be used to study human evolution. (Ellegren, 2000; Imad et al., 2014). The classification of Besides, information from DNA typing is important for the DNA sequences is determined by the length of the medico-legal matters with polymorphisms leading to more core repeat unit and the number of adjacent repeat units. -

Combinatorial Genomic Data Refute the Human Chromosome 2 Evolutionary Fusion and Build a Model of Functional Design for Interstitial Telomeric Repeats

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 8 Print Reference: Pages 222-228 Article 32 2018 Combinatorial Genomic Data Refute the Human Chromosome 2 Evolutionary Fusion and Build a Model of Functional Design for Interstitial Telomeric Repeats Jeffrey P. Tomkins Institute for Creation Research Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings Part of the Biology Commons, and the Genomics Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Tomkins, J.P. 2018. Combinatorial genomic data refute the human chromosome 2 evolutionary fusion and build a model of functional design for interstitial telomeric repeats. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism, ed. J.H. Whitmore, pp. 222–228. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship. Tomkins, J.P. 2018. Combinatorial genomic data refute the human chromosome 2 evolutionary fusion and build a model of functional design for interstitial telomeric repeats. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Creationism, ed. J.H. Whitmore, pp. 222–228. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Creation Science Fellowship. COMBINATORIAL GENOMIC DATA REFUTE THE HUMAN CHROMOSOME 2 EVOLUTIONARY FUSION AND BUILD A MODEL OF FUNCTIONAL DESIGN FOR INTERSTITIAL TELOMERIC REPEATS Jeffrey P. -

Gene Knockdown of CENPA Reduces Sphere Forming Ability and Stemness of Glioblastoma Initiating Cells

Neuroepigenetics 7 (2016) 6–18 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neuroepigenetics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/nepig Gene knockdown of CENPA reduces sphere forming ability and stemness of glioblastoma initiating cells Jinan Behnan a,1, Zanina Grieg b,c,1, Mrinal Joel b,c, Ingunn Ramsness c, Biljana Stangeland a,b,⁎ a Department of Molecular Medicine, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, The Medical Faculty, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway b Norwegian Center for Stem Cell Research, Department of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway c Vilhelm Magnus Laboratory for Neurosurgical Research, Institute for Surgical Research and Department of Neurosurgery, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway article info abstract Article history: CENPA is a centromere-associated variant of histone H3 implicated in numerous malignancies. However, the Received 20 May 2016 role of this protein in glioblastoma (GBM) has not been demonstrated. GBM is one of the most aggressive Received in revised form 23 July 2016 human cancers. GBM initiating cells (GICs), contained within these tumors are deemed to convey Accepted 2 August 2016 characteristics such as invasiveness and resistance to therapy. Therefore, there is a strong rationale for targeting these cells. We investigated the expression of CENPA and other centromeric proteins (CENPs) in Keywords: fi CENPA GICs, GBM and variety of other cell types and tissues. Bioinformatics analysis identi ed the gene signature: fi Centromeric proteins high_CENP(AEFNM)/low_CENP(BCTQ) whose expression correlated with signi cantly worse GBM patient Glioblastoma survival. GBM Knockdown of CENPA reduced sphere forming ability, proliferation and cell viability of GICs. We also Brain tumor detected significant reduction in the expression of stemness marker SOX2 and the proliferation marker Glioblastoma initiating cells and therapeutic Ki67. -

CD56+ T-Cells in Relation to Cytomegalovirus in Healthy Subjects and Kidney Transplant Patients

CD56+ T-cells in Relation to Cytomegalovirus in Healthy Subjects and Kidney Transplant Patients Institute of Infection and Global Health Department of Clinical Infection, Microbiology and Immunology Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Mazen Mohammed Almehmadi December 2014 - 1 - Abstract Human T cells expressing CD56 are capable of tumour cell lysis following activation with interleukin-2 but their role in viral immunity has been less well studied. The work described in this thesis aimed to investigate CD56+ T-cells in relation to cytomegalovirus infection in healthy subjects and kidney transplant patients (KTPs). Proportions of CD56+ T cells were found to be highly significantly increased in healthy cytomegalovirus-seropositive (CMV+) compared to cytomegalovirus-seronegative (CMV-) subjects (8.38% ± 0.33 versus 3.29%± 0.33; P < 0.0001). In donor CMV-/recipient CMV- (D-/R-)- KTPs levels of CD56+ T cells were 1.9% ±0.35 versus 5.42% ±1.01 in D+/R- patients and 5.11% ±0.69 in R+ patients (P 0.0247 and < 0.0001 respectively). CD56+ T cells in both healthy CMV+ subjects and KTPs expressed markers of effector memory- RA T-cells (TEMRA) while in healthy CMV- subjects and D-/R- KTPs the phenotype was predominantly that of naïve T-cells. Other surface markers, CD8, CD4, CD58, CD57, CD94 and NKG2C were expressed by a significantly higher proportion of CD56+ T-cells in healthy CMV+ than CMV- subjects. Functional studies showed levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α, as well as granzyme B and CD107a were significantly higher in CD56+ T-cells from CMV+ than CMV- subjects following stimulation with CMV antigens. -

Discovery of the First Genome-Wide Significant Risk Loci for ADHD

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/145581; this version posted June 3, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for ADHD Ditte Demontis,1,2,3† Raymond K. Walters,4,5† Joanna Martin,5,6,7 Manuel Mattheisen,1,2,3,8,9 Thomas D. Als,1,2,3 Esben Agerbo,1,10,11 Rich Belliveau,5 Jonas Bybjerg-Grauholm,1,12 Marie Bækvad-Hansen,1,12 Felecia Cerrato,5 Kimberly Chambert,5 Claire Churchhouse,4,5,13 Ashley Dumont,5 Nicholas Eriksson,14 Michael Gandal,15,16,17,18 Jacqueline Goldstein,4,5,13 Jakob Grove,1,2,3,19 Christine S. Hansen,1,12,20 Mads E. Hauberg,1,2,3 Mads V. Hollegaard,1,12 Daniel P. Howrigan,4,5 Hailiang Huang,4,5 Julian Maller,5,21 Alicia R. Martin,4,5,13 Jennifer Moran,5 Jonatan Pallesen,1,2,3 Duncan S. Palmer,4,5 Carsten B. Pedersen,1,10,11 Marianne G. Pedersen,1,10,11 Timothy Poterba,4,5,13 Jesper B. Poulsen,1,12 Stephan Ripke,4,5,13,22 Elise B. Robinson,4,23 Kyle F. Satterstrom,4,5,13 Christine Stevens,5 Patrick Turley,4,5 Hyejung Won,15,16 ADHD Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC), Early Lifecourse & Genetic Epidemiology (EAGLE) Consortium, 23andMe Research Team, Ole A. -

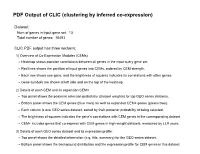

PDF Output of CLIC (Clustering by Inferred Co-Expression)

PDF Output of CLIC (clustering by inferred co-expression) Dataset: Num of genes in input gene set: 13 Total number of genes: 16493 CLIC PDF output has three sections: 1) Overview of Co-Expression Modules (CEMs) Heatmap shows pairwise correlations between all genes in the input query gene set. Red lines shows the partition of input genes into CEMs, ordered by CEM strength. Each row shows one gene, and the brightness of squares indicates its correlations with other genes. Gene symbols are shown at left side and on the top of the heatmap. 2) Details of each CEM and its expansion CEM+ Top panel shows the posterior selection probability (dataset weights) for top GEO series datasets. Bottom panel shows the CEM genes (blue rows) as well as expanded CEM+ genes (green rows). Each column is one GEO series dataset, sorted by their posterior probability of being selected. The brightness of squares indicates the gene's correlations with CEM genes in the corresponding dataset. CEM+ includes genes that co-express with CEM genes in high-weight datasets, measured by LLR score. 3) Details of each GEO series dataset and its expression profile: Top panel shows the detailed information (e.g. title, summary) for the GEO series dataset. Bottom panel shows the background distribution and the expression profile for CEM genes in this dataset. Overview of Co-Expression Modules (CEMs) with Dataset Weighting Scale of average Pearson correlations Num of Genes in Query Geneset: 13. Num of CEMs: 1. 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 Cenpk Cenph Cenpp Cenpu Cenpn Cenpq Cenpl Apitd1 -

1 Supporting Information for a Microrna Network Regulates

Supporting Information for A microRNA Network Regulates Expression and Biosynthesis of CFTR and CFTR-ΔF508 Shyam Ramachandrana,b, Philip H. Karpc, Peng Jiangc, Lynda S. Ostedgaardc, Amy E. Walza, John T. Fishere, Shaf Keshavjeeh, Kim A. Lennoxi, Ashley M. Jacobii, Scott D. Rosei, Mark A. Behlkei, Michael J. Welshb,c,d,g, Yi Xingb,c,f, Paul B. McCray Jr.a,b,c Author Affiliations: Department of Pediatricsa, Interdisciplinary Program in Geneticsb, Departments of Internal Medicinec, Molecular Physiology and Biophysicsd, Anatomy and Cell Biologye, Biomedical Engineeringf, Howard Hughes Medical Instituteg, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA-52242 Division of Thoracic Surgeryh, Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada-M5G 2C4 Integrated DNA Technologiesi, Coralville, IA-52241 To whom correspondence should be addressed: Email: [email protected] (M.J.W.); yi- [email protected] (Y.X.); Email: [email protected] (P.B.M.) This PDF file includes: Materials and Methods References Fig. S1. miR-138 regulates SIN3A in a dose-dependent and site-specific manner. Fig. S2. miR-138 regulates endogenous SIN3A protein expression. Fig. S3. miR-138 regulates endogenous CFTR protein expression in Calu-3 cells. Fig. S4. miR-138 regulates endogenous CFTR protein expression in primary human airway epithelia. Fig. S5. miR-138 regulates CFTR expression in HeLa cells. Fig. S6. miR-138 regulates CFTR expression in HEK293T cells. Fig. S7. HeLa cells exhibit CFTR channel activity. Fig. S8. miR-138 improves CFTR processing. Fig. S9. miR-138 improves CFTR-ΔF508 processing. Fig. S10. SIN3A inhibition yields partial rescue of Cl- transport in CF epithelia. -

Supplementary Table S5. Differentially Expressed Gene Lists of PD-1High CD39+ CD8 Tils According to 4-1BB Expression Compared to PD-1+ CD39- CD8 Tils

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) J Immunother Cancer Supplementary Table S5. Differentially expressed gene lists of PD-1high CD39+ CD8 TILs according to 4-1BB expression compared to PD-1+ CD39- CD8 TILs Up- or down- regulated genes in Up- or down- regulated genes Up- or down- regulated genes only PD-1high CD39+ CD8 TILs only in 4-1BBneg PD-1high CD39+ in 4-1BBpos PD-1high CD39+ CD8 compared to PD-1+ CD39- CD8 CD8 TILs compared to PD-1+ TILs compared to PD-1+ CD39- TILs CD39- CD8 TILs CD8 TILs IL7R KLRG1 TNFSF4 ENTPD1 DHRS3 LEF1 ITGA5 MKI67 PZP KLF3 RYR2 SIK1B ANK3 LYST PPP1R3B ETV1 ADAM28 H2AC13 CCR7 GFOD1 RASGRP2 ITGAX MAST4 RAD51AP1 MYO1E CLCF1 NEBL S1PR5 VCL MPP7 MS4A6A PHLDB1 GFPT2 TNF RPL3 SPRY4 VCAM1 B4GALT5 TIPARP TNS3 PDCD1 POLQ AKAP5 IL6ST LY9 PLXND1 PLEKHA1 NEU1 DGKH SPRY2 PLEKHG3 IKZF4 MTX3 PARK7 ATP8B4 SYT11 PTGER4 SORL1 RAB11FIP5 BRCA1 MAP4K3 NCR1 CCR4 S1PR1 PDE8A IFIT2 EPHA4 ARHGEF12 PAICS PELI2 LAT2 GPRASP1 TTN RPLP0 IL4I1 AUTS2 RPS3 CDCA3 NHS LONRF2 CDC42EP3 SLCO3A1 RRM2 ADAMTSL4 INPP5F ARHGAP31 ESCO2 ADRB2 CSF1 WDHD1 GOLIM4 CDK5RAP1 CD69 GLUL HJURP SHC4 GNLY TTC9 HELLS DPP4 IL23A PITPNC1 TOX ARHGEF9 EXO1 SLC4A4 CKAP4 CARMIL3 NHSL2 DZIP3 GINS1 FUT8 UBASH3B CDCA5 PDE7B SOGA1 CDC45 NR3C2 TRIB1 KIF14 TRAF5 LIMS1 PPP1R2C TNFRSF9 KLRC2 POLA1 CD80 ATP10D CDCA8 SETD7 IER2 PATL2 CCDC141 CD84 HSPA6 CYB561 MPHOSPH9 CLSPN KLRC1 PTMS SCML4 ZBTB10 CCL3 CA5B PIP5K1B WNT9A CCNH GEM IL18RAP GGH SARDH B3GNT7 C13orf46 SBF2 IKZF3 ZMAT1 TCF7 NECTIN1 H3C7 FOS PAG1 HECA SLC4A10 SLC35G2 PER1 P2RY1 NFKBIA WDR76 PLAUR KDM1A H1-5 TSHZ2 FAM102B HMMR GPR132 CCRL2 PARP8 A2M ST8SIA1 NUF2 IL5RA RBPMS UBE2T USP53 EEF1A1 PLAC8 LGR6 TMEM123 NEK2 SNAP47 PTGIS SH2B3 P2RY8 S100PBP PLEKHA7 CLNK CRIM1 MGAT5 YBX3 TP53INP1 DTL CFH FEZ1 MYB FRMD4B TSPAN5 STIL ITGA2 GOLGA6L10 MYBL2 AHI1 CAND2 GZMB RBPJ PELI1 HSPA1B KCNK5 GOLGA6L9 TICRR TPRG1 UBE2C AURKA Leem G, et al. -

1 AGING Supplementary Table 2

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLES Supplementary Table 1. Details of the eight domain chains of KIAA0101. Serial IDENTITY MAX IN COMP- INTERFACE ID POSITION RESOLUTION EXPERIMENT TYPE number START STOP SCORE IDENTITY LEX WITH CAVITY A 4D2G_D 52 - 69 52 69 100 100 2.65 Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ B 4D2G_E 52 - 69 52 69 100 100 2.65 Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ C 6EHT_D 52 - 71 52 71 100 100 3.2Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ D 6EHT_E 52 - 71 52 71 100 100 3.2Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ E 6GWS_D 41-72 41 72 100 100 3.2Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ F 6GWS_E 41-72 41 72 100 100 2.9Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ G 6GWS_F 41-72 41 72 100 100 2.9Å PCNA X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ H 6IIW_B 2-11 2 11 100 100 1.699Å UHRF1 X-RAY DIFFRACTION √ www.aging-us.com 1 AGING Supplementary Table 2. Significantly enriched gene ontology (GO) annotations (cellular components) of KIAA0101 in lung adenocarcinoma (LinkedOmics). Leading Description FDR Leading Edge Gene EdgeNum RAD51, SPC25, CCNB1, BIRC5, NCAPG, ZWINT, MAD2L1, SKA3, NUF2, BUB1B, CENPA, SKA1, AURKB, NEK2, CENPW, HJURP, NDC80, CDCA5, NCAPH, BUB1, ZWILCH, CENPK, KIF2C, AURKA, CENPN, TOP2A, CENPM, PLK1, ERCC6L, CDT1, CHEK1, SPAG5, CENPH, condensed 66 0 SPC24, NUP37, BLM, CENPE, BUB3, CDK2, FANCD2, CENPO, CENPF, BRCA1, DSN1, chromosome MKI67, NCAPG2, H2AFX, HMGB2, SUV39H1, CBX3, TUBG1, KNTC1, PPP1CC, SMC2, BANF1, NCAPD2, SKA2, NUP107, BRCA2, NUP85, ITGB3BP, SYCE2, TOPBP1, DMC1, SMC4, INCENP. RAD51, OIP5, CDK1, SPC25, CCNB1, BIRC5, NCAPG, ZWINT, MAD2L1, SKA3, NUF2, BUB1B, CENPA, SKA1, AURKB, NEK2, ESCO2, CENPW, HJURP, TTK, NDC80, CDCA5, BUB1, ZWILCH, CENPK, KIF2C, AURKA, DSCC1, CENPN, CDCA8, CENPM, PLK1, MCM6, ERCC6L, CDT1, HELLS, CHEK1, SPAG5, CENPH, PCNA, SPC24, CENPI, NUP37, FEN1, chromosomal 94 0 CENPL, BLM, KIF18A, CENPE, MCM4, BUB3, SUV39H2, MCM2, CDK2, PIF1, DNA2, region CENPO, CENPF, CHEK2, DSN1, H2AFX, MCM7, SUV39H1, MTBP, CBX3, RECQL4, KNTC1, PPP1CC, CENPP, CENPQ, PTGES3, NCAPD2, DYNLL1, SKA2, HAT1, NUP107, MCM5, MCM3, MSH2, BRCA2, NUP85, SSB, ITGB3BP, DMC1, INCENP, THOC3, XPO1, APEX1, XRCC5, KIF22, DCLRE1A, SEH1L, XRCC3, NSMCE2, RAD21. -

Role of the Transcriptional Regulator SP140 in Resistance

RESEARCH ARTICLE Role of the transcriptional regulator SP140 in resistance to bacterial infections via repression of type I interferons Daisy X Ji1†, Kristen C Witt1†, Dmitri I Kotov1,2, Shally R Margolis1, Alexander Louie1, Victoria Cheve´ e1, Katherine J Chen1,2, Moritz M Gaidt1, Harmandeep S Dhaliwal3, Angus Y Lee3, Stephen L Nishimura4, Dario S Zamboni5, Igor Kramnik6, Daniel A Portnoy1,7,8, K Heran Darwin9, Russell E Vance1,2,3* 1Division of Immunology and Pathogenesis, Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, United States; 2Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, United States; 3Cancer Research Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, United States; 4Department of Pathology, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, United States; 5Department of Cell Biology, Ribeira˜ o Preto Medical School, University of Sa˜ o Paulo, Sa˜ o Paulo, Brazil; 6The National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratory, Department of Medicine (Pulmonary Center), and Department of Microbiology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, United States; 7Division of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Structural Biology, Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, United States; 8Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, United States; 9Department of Microbiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, United States *For correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Type I interferons (IFNs) are essential for anti-viral immunity, but often impair †These authors contributed protective immune responses during bacterial infections. An important question is how type I IFNs equally to this work are strongly induced during viral infections, and yet are appropriately restrained during bacterial infections. -

Análise Integrativa De Perfis Transcricionais De Pacientes Com

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE MEDICINA DE RIBEIRÃO PRETO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM GENÉTICA ADRIANE FEIJÓ EVANGELISTA Análise integrativa de perfis transcricionais de pacientes com diabetes mellitus tipo 1, tipo 2 e gestacional, comparando-os com manifestações demográficas, clínicas, laboratoriais, fisiopatológicas e terapêuticas Ribeirão Preto – 2012 ADRIANE FEIJÓ EVANGELISTA Análise integrativa de perfis transcricionais de pacientes com diabetes mellitus tipo 1, tipo 2 e gestacional, comparando-os com manifestações demográficas, clínicas, laboratoriais, fisiopatológicas e terapêuticas Tese apresentada à Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências. Área de Concentração: Genética Orientador: Prof. Dr. Eduardo Antonio Donadi Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Geraldo A. S. Passos Ribeirão Preto – 2012 AUTORIZO A REPRODUÇÃO E DIVULGAÇÃO TOTAL OU PARCIAL DESTE TRABALHO, POR QUALQUER MEIO CONVENCIONAL OU ELETRÔNICO, PARA FINS DE ESTUDO E PESQUISA, DESDE QUE CITADA A FONTE. FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA Evangelista, Adriane Feijó Análise integrativa de perfis transcricionais de pacientes com diabetes mellitus tipo 1, tipo 2 e gestacional, comparando-os com manifestações demográficas, clínicas, laboratoriais, fisiopatológicas e terapêuticas. Ribeirão Preto, 2012 192p. Tese de Doutorado apresentada à Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo. Área de Concentração: Genética. Orientador: Donadi, Eduardo Antonio Co-orientador: Passos, Geraldo A. 1. Expressão gênica – microarrays 2. Análise bioinformática por module maps 3. Diabetes mellitus tipo 1 4. Diabetes mellitus tipo 2 5. Diabetes mellitus gestacional FOLHA DE APROVAÇÃO ADRIANE FEIJÓ EVANGELISTA Análise integrativa de perfis transcricionais de pacientes com diabetes mellitus tipo 1, tipo 2 e gestacional, comparando-os com manifestações demográficas, clínicas, laboratoriais, fisiopatológicas e terapêuticas.