Global University Rankings in the Polish Context: the University of Warsaw, a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESR2 the Role of Culture and Tradition in the Shift Towards Illiberal

Page 1 of 3 Job Description FATIGUE Early Stage Researcher Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Institute of European Studies The Institute of European Studies of the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland is seeking to appoint three high-calibre Early Stage Researchers (ESR) to join the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Innovative Training Network on ‘Delayed Transformational Fatigue in Central and Eastern Europe: Responding to the Rise of Illiberalism/Populism’ (FATIGUE). Position Early Stage Researcher 2: The role of culture and tradition in the shift towards illiberal democracy Location: Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland (Years 1 and 3) and Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic (Year 2) Working Time: Full Time (156 hours per month) Duration: Fixed-Term (1st August 2018 – 31th July 2021) Salary: €28,512.48 (before employer and employee deductions – fixed for period of the appointment) per annum, plus a monthly taxable mobility allowance of €600 – paid in Polish złoty using an appropriate conversion rate. If applicable, an additional taxable monthly family allowance of €500. About FATIGUE Following the collapse of state socialism, the liberalisation of public life, democratisation of politics, abolition of state-run economies and the introduction of markets commenced in the states of the former Soviet bloc. These necessary yet socially costly transformations never ran smoothly and in the same direction in all the post-communist states but by the mid-2000s the most successful countries, clustered in Central Europe and the Baltic, seemed to have managed to consolidate liberal democracy. Then something snapped. The political trajectory veered off in new directions as populist parties started gaining more support. -

MEDICAL UNIVERSITIES in POLAND 1 POLAND Facts and FIGURES MEDICAL UNIVERSITIES in POLAND

MEDICAL UNIVERSITIES IN POLAND 1 POLAND faCTS AND FIGURES MEDICAL UNIVERSITIES IN POLAND OFFICIAL NAME LOCATION TIME ZONE Republic of Poland (short form: Poland is situated in Central CET (UTC+1) PAGE 2 PAGE 5 PAGE 7 Poland, in Polish: Polska) Europe and borders Germany, CALLING CODE the Czech Republic, Slovakia, POPULATION (2019) +48 Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and WHY HIGHER POLISH 38 million Russia INTERNET DOMAIN POLAND? EDUCATION CONTRIBUTION OFFICIAL LANGUAGE .pl ENTERED THE EU Polish 2004 STUDENTS (2017/18) IN POLAND TO MEDICAL CAPITAL 1.29 million CURRENCY (MAY 2019) SCIENCES Warsaw (Warszawa) 1 zloty (PLN) MEDICAL STUDENTS (2017/18) GOVERNMENT 1 PLN = 0.23 € 1 PLN = 0.26 $ 64 thousand parliamentary republic PAGE 12 PAGE 14 PAGE 44 MEDICAL DEGREE ACCREDITATION UNIVERSITIES PROGRAMMES & QUALITY Warsaw ● MINIGUIDE IN ENGLISH ASSURANCE 2 3 WHY POLAND? Top countries of origin among Are you interested in studying medicine abroad? Good, then you have the right brochure in front of foreign medical you! This publication explains briefly what the Polish higher education system is like, introduces Polish students in medical universities and lists the degree programmes that are taught in English. Poland If you are looking for high-quality medical education provided by experienced and inspired teachers – Polish medical universities are some of the best options. We present ten of the many good reasons for Polish medical international students to choose Poland. universities have attracted the interest of students from a wide ACADEMIC TRADITION other types of official documentation for all variety of backgrounds completed courses. If you complete a full degree from all around the Poland’s traditions of academic education go or a diploma programme, you will receive a globe. -

Odo Bujwid — an Eminent Polish Bacteriologist and Professor at the Jagiellonian University

FOLIA MEDICA CRACOVIENSIA 15 Vol. LIV, 4, 2014: 15–20 PL ISSN 0015-5616 KATARZYNA TALAGA1, Małgorzata Bulanda2 ODO BUJWID — AN EMINENT POLISH BACTERIOLOGIST AND PROFESSOR AT THE JAGIELLONIAN UNIVERSITY Abstract: To celebrate the 650th Jubilee of the Jagiellonian University, we would like to give an outline of the life and work of Odo Bujwid, known as the father of Polish bacteriology. The intention of the authors is to recall the beginnings of Polish bacteriology, the doyen of which was Professor Odo Buj- wid, a great Polish scholar who also served as a promoter of bacteriology, a field created in the 19th century. He published about 400 publications, including approx. 200 in the field of bacteriology. He is credited with popularizing the research of the fathers of global bacteriology — Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur — and applying it practically, as well as educating Polish microbiologists who constituted the core of the scientific staff during the interwar period. Key words: Polish bacteriology, Cracow, Odo Bujwid, Jagiellonian University. To celebrate the 650th Jubilee of the Jagiellonian University, we would like to give an outline of the life and work of Odo Bujwid, known as the father of Polish bacteriology. In accordance with the motto accompanying the celebration of this major anniversary, i.e., “Inspired by the past, we are creating the future 1364– 2014” and as employees of the Jagiellonian University, where this great Polish scholar was teaching and promoting the field formed in the 19th century — bacteriology — by looking back at the life and scientific work of Bujwid, we would like to draw inspiration and willingness to do academic work. -

POLAND 7 Institutions Ranked in at Least One Subject 3 Institutions in World's Top 200 for at Least One Subject

QS World University Rankings by Subject 2014 COUNTRY FILE 2222 7 3institutions cited by academics in at least one subject POLAND 7 institutions ranked in at least one subject 3 institutions in world's top 200 for at least one subject INSTITUTIONAL REPRESENTATION BY SUBJECT TOP INSTITUTIONS BY SUBJECT ARTS & HUMANITIES ENGLISH English Language & Literature History Linguistics Modern Languages HISTORY 1 Jagiellonian University [101-150] 1 University of Warsaw 1 University of Warsaw [101-150] 1 Jagiellonian University [51-100] 2 University of Warsaw [101-150] 2 Jagiellonian University 2 Jagiellonian University 2 University of Warsaw [101-150] LINGUISTICS 3 University of Wroclaw [201-250] 3 University of Wroclaw 3 University of Wroclaw 3 University of Gdansk [301-400] 4 University of Rzeszów 4 Polytechnic University, Cracow 4 Lodz University 4 University of Wroclaw LANGUAGES 5 Warsaw University of Life Sciences 5 University of Rzeszów 5 University of Silesia 5 Lodz University ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY PHILOSOPHY Philosophy Computer Science & Information Systems Engineering - Chemical Engineering - Civil & Structural 1 University of Warsaw [101-150] 1 University of Warsaw [201-250] 1 Warsaw University of Technology 1 Warsaw University of Technology COMPUTER SCIENCE 2 Jagiellonian University 2 Warsaw University of Technology [201-250] 2 Polytechnic University, Cracow 2 Polytechnic University, Cracow 3 University of Wroclaw 3 Jagiellonian University 3 Polish Academy of Sciences 3 Wroclaw University of Technology CHEMICAL ENGINEERING 4 Poznan School -

Jagiellonian University

NJUsletter ISSN: 1689-037X TWO PRESIDENTIAL VISITS 69 SPRING/ SUMMER RECTORIAL ELECTIONS 2020 IN RESPONSE TO COVID-19 JAGIELLONIAN UNIVERSITY Faculty of Law and Administration Faculty of Philosophy Faculty of History Faculty of Philology Faculty of Polish Studies Faculty of Physics, Astronomy and Applied Computer Science Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science Faculty of Chemistry Faculty of Biology Faculty of Geography and Geology Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology Faculty of Management and Social Communication Faculty of International and Political Studies Faculty of Medicine Faculty of Pharmacy Faculty of Health Sciences Founded in 1364 3 16 faculties campuses 35,922 students, including 4,743 international, over 90 nationalities PhD students Each = 2,000 students = International students 2,356 94 158 8,342 study specialities employees, including programmes 4,509 academics USOS data as of 31.07.2020 In this issue... UNIVERSITY NEWS 2 French President Emmanuel Macron visits the Jagiellonian University Editor: 4 Education means being a complete person JU International 2 Relations Office – Maltese President lecturing at JU 4 6 New JU authorities © Dział Współpracy 7 100th Anniversary of Pope John Paul II’s Międzynarodowej UJ, 2020 birth Publications Officer: FEATURES Agnieszka Kołodziejska-Skrobek 9 JU in touch with the world 10 Coimbra Group 3-Minute Thesis Language consultant: 11 UNA.TEN Maja Nowak-Bończa 6 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Design: Dział Współpracy 14 UNA EUROPA 1Europe kick-off meeting Międzynarodowej UJ 16 International Students 2020 Gala 17 Polish-Brazilian botanical co-operation Translation: 19 DIGIPASS in Amsterdam Agnieszka Kołodziejska-Skrobek 20 From an ex-native speaker: On Becoming Polish 11 Edited in Poland by: Towarzystwo Słowaków STUDENT LIFE w Polsce www.tsp.org.pl 21 Bonjour – Hi. -

Jagiellonian University Ul. Gołębia 24 31-007 Kraków, Poland Phone +48 12 663 11 42, +48 12 663 12 50 Fax + 48 12 422 66 65 E-Mail: [email protected]

1. Research institution data: Jagiellonian University Ul. Gołębia 24 31-007 Kraków, Poland Phone +48 12 663 11 42, +48 12 663 12 50 Fax + 48 12 422 66 65 e-mail: [email protected] Faculty of Biology, Jagiellonian University ul. Gronostajowa 7 30-387 Kraków, Poland Phone +48 12 664 67 55, +48 664 60 47 Fax +48 12 664 69 08 e-mail [email protected] 2. Type of research institution: 1) basic organisational unit of higher education institution 3. Head of the institution: Prof. dr hab. Stanisław Kistryn, Vice-Rector for Research and Structural Funds 4. Contact information of designated person(s) for applicants and the NCN: first and last name, position, e-mail address, phone number, correspondence address): Prof. dr hab. Wiesław Babik Scientific Director, Institute of Environmental Sciences Email: [email protected] Phone: +48 12 664 51 71 Institute of Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Jagiellonian University Gronostajowa 7 30-387 Kraków Poland 5. Research discipline in which the strong international position of the institution ensures establishing a Dioscuri Centre: Life sciences Evolutionary and environmental biology 1 6. Description of important research achievements from the selected discipline from the last 5 years including a list of the most important publications, patents, other in Evolutionary and environmental biology): Ecotoxicology: A model explaining the equilibrium concentration of toxic metals in an organism as the net result of gut cell death and replacement rates [1]. Evolution of the Major Histocompatibility genes: critical evaluation of the role of MHC supertypes in promoting trans-species polymorphism [2]; modeling showed that both Red Queen dynamics and sexual selection drive the adaptive evolution of the MHC genes [3,4]. -

Improvement of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function and Left Heart

CLINICAL CARDIOLOGY Cardiology Journal 2018, Vol. 25, No. 1, 97–105 DOI: 10.5603/CJ.a2017.0059 Copyright © 2018 Via Medica ORIGINAL ARTICLE ISSN 1897–5593 Improvement of left ventricular diastolic function and left heart morphology in young women with morbid obesity six months after bariatric surgery Katarzyna Kurnicka1, Justyna Domienik-Karłowicz1, Barbara Lichodziejewska1, Maksymilian Bielecki2, Marta Kozłowska1, Sylwia Goliszek1, Olga Dzikowska-Diduch1, Wojciech Lisik3, Maciej Kosieradzki3, Piotr Pruszczyk1 1Department of Internal Medicine and Cardiology, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland 2Department of Psychology, SWPS University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Warsaw, Poland 3Department of General Surgery and Transplantology, Medical University of Warsaw, Poland Abstract Background: Obesity contributes to left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction (LVDD) and may lead to diastolic heart failure. Weight loss (WL) after bariatric surgery (BS) may influence LV morphology and function. Using echocardiography, this study assessed the effect of WL on LV diastolic function (LVDF) and LV and left atrium (LA) morphology 6 months after BS in young women with morbid obesity. Methods: Echocardiography was performed in 60 women with body mass index ≥ 40 kg/m², aged 37.1 ± ± 9.6 years prior to and 6 months after BS. In 38 patients, well-controlled arterial hypertension was present. Heart failure, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation and mitral stenosis were exclusion criteria. Parameters of LV and LA morphology were obtained. To evaluate LVDF, mitral peak early (E) and atrial (A) velocities, E-deceleration time (DcT), pulmonary vein S, D and A reversal velocities were measured. Peak early diastolic mitral annular velocities (E’) and E/E’ were assessed. Results: Mean WL post BS was 35.7 kg (27%). -

1 Master of Arts Thesis Euroculture Uppsala University (Home)

Master of Arts Thesis Euroculture Uppsala University (Home) Jagiellonian University (Host) July 2015 Intangible heritage in multicultural Brussels: A case study of identity and performance. Submitted by: Catherine Burkinshaw 850107P248 1110545 [email protected] Supervised by: Dr Annika Berg, Uppsala University Dr Krzysztof Kowalski, Jagiellonian University Uppsala, 27 July, 2015 1 Master of Arts Programme Euroculture Declaration I, Catherine Burkinshaw, hereby declare that this thesis, entitled “Intangible heritage in multicultural Brussels: A case study of identity and performance”, submitted as partial requirement for the MA Programme Euroculture, is my own original work and expressed in my own words. Any use made within this text of works of other authors in any form (e.g. ideas, figures, texts, tables, etc.) are properly acknowledged in the text as well as in the bibliography. I hereby also acknowledge that I was informed about the regulations pertaining to the assessment of the MA thesis Euroculture and about the general completion rules for the Master of Arts Programme Euroculture. 27 July 2015 2 Acknowledgements My deepest thanks to all of the following people for their kind assistance, input and support Dr Annika Berg and Dr Krzysztof Kowalski, my enthusiastic supervisors My inspirational classmates, Emelie Milde Jacobson, Caitlin Boulter and Magdalena Cortese Coelho All the dedicated Euroculture staff at Uppsala University and Jagiellonian University All the friends and family who supported me in the writing of -

Planning Education in Poland

Planning Education in Poland Andrea Frank and Izabela Mironowicz Case study prepared for Planning Sustainable Cities: Global Report on Human Settlements 2009 Available from http://www.unhabitat.org/grhs/2009 Dr. Andrea I. Frank is a lecturer, School of City and Regional Planning, Cardiff University. She is also the Deputy Director (Planning, Housing & Transport) of the Centre for Education in the Built Environment, which has a UK-wide remit to work with relevant university departments to enhance teaching and student learning experiences and disseminate good pedagogical practice through work- shops and conferences. Her recent publications include the annotated ‘CPL Bibliography 376: Three decades of Thought on Planning Education’ in the Journal of Planning Literature (2006) and articles on skills and internationalization in planning education provision. Comments may be sent to the author by email: [email protected]. Dr. Izabela Mironowicz is Assistant Professor, Department of Spatial Planning (Faculty of Architec- ture), Wrocław University of Technology. She is a member of the Polish Task Force for Planning Education and Career Development, which has a remit to facilitate the cooperation of Polish planning schools. Her research focuses on urban development and urban transformations. She is a practicing urban planner and consultant, and a board member of the Commission on Architecture and Town Planning in Wrocław, an advisory body to the mayor and local authority representatives. Comments may be sent to the author by email: [email protected]. -

Facing History's Poland Study Tour Confirmed Speakers and Tour Guides

Facing History’s Poland Study Tour Confirmed Speakers and Tour Guides Speakers Jolanta Ambrosewicz-Jacobs, Director Center for Holocaust Studies at the Jagiellonian University Dr. Jolanta Ambrosewicz-Jacobs is the Director of the Center for Holocaust Studies at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. She received her Ph.D. in Humanities from Jagiellonian University. Dr. Ambrosewicz-Jacobs was a fellow at several institutions. She was a Pew Fellow at the Center for the Study of Human Rights at Columbia University, a visiting fellow at Oxford University and at Cambridge University, and a DAAD fellow at the Memorial and Educational Site House of the Wannsee Conference. She is also the author of Me – Us – Them. Ethnic Prejudices and Alternative Methods of Education: The Case of Poland and has published more than 50 articles on anti-Semitism in Poland, memory of the Holocaust, and education about the Holocaust. Anna Bando, President Association of Polish Righteous Among Nations The Association of Polish Righteous Among Nations was founded in 1985. Its members are Polish citizens who have been honored with the title and medal of Righteous Among the Nations. The goals of the society are to disseminate information about the occupation, the Holocaust and the actions of the Righteous, and to fight against anti-Semitism and xenophobia. Anna Bando, nee Stupnicka, together with her mother, Janina Stupnicka, were honored in 1984 as Righteous Among the Nations for their rescue of Liliana Alter, an eleven year old Jewish girl, from the Warsaw ghetto. The two smuggled her out of the ghetto as well as provided her false papers and sheltered her until the end of the war. -

AEN Secretariat General Update

AGM – 27 April 2017 Agenda Item 12 (i) Action required – for information AEN Secretariat General Update Secretariat Update The AEN Secretariat is situated within Western Sydney University, having transitioned from Deakin University in late 2015. The current Secretariat Officer is Rohan McCarthy-Gill, having taken over this role upon the departure of Caroline Reid from Western Sydney University in August 2016. There has been some impact upon the AEN Secretariat’s business operations due to staffing changes and shortages within Western Sydney University’s international office. However, as at March 2017, operations have largely normalised. The Secretariat is scheduled to move to Edith Cowan University in November 2017 and very preliminary discussions have started between Western Sydney University and Edith Cowan University around this transition. AEN-UN Agreement After the process of renewal, the AEN-UN Agreement renewal was finalised on 4 July 2016, upon final signature by the President of the Utrecht Network. AEN Website The AEN website continues to pose some challenges and due to technical problems and resourcing issues in the AEN Secretariat there is still some work that needs to be done to enhance it. This is scheduled for the second half of 2017. A superficial update of the website was conducted in late 2016, including an update of process instructions and tools for AEN members, contact details and FAQs. Macquarie University The AEN Secretariat was notified by Macquarie University on 31 October 2016 that, due to a realignment of the University’s mobility partnerships with its strategic priorities, that it would withdraw from the AEN consortium, with effect from 1 January 2017. -

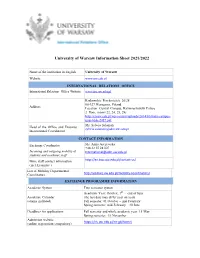

University of Warsaw Information Sheet 2021/2022

University of Warsaw Information Sheet 2021/2022 Name of the institution in English University of Warsaw Website www.uw.edu.pl INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS OFFICE International Relations Office Website www.iro.uw.edu.pl Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28 00-927 Warszawa, Poland Address Location: Central Campus, Kazimierzowski Palace 2. floor, rooms 22, 24, 28, 29c http://en.uw.edu.pl/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/main-campus- map-blok-2017.pdf Ms. Sylwia Salamon Head of the Office and Erasmus [email protected] Institutional Coordinator CONTACT INFORMATION Exchange Coordinator Ms. Anna Jarczewska +48 22 55 24 007 Incoming and outgoing mobility of [email protected] students and academic staff More staff contact information http://en.bwz.uw.edu.pl/contact-us/ (incl. Erasmus+) List of Mobility Departmental Coordinators http://en.bwz.uw.edu.pl/mobility-coordinators/ EXCHANGE PROGRAMME INFORMATION Academic System Two semester system Academic Year: October, 1st - end of June Academic Calendar (the last date may differ year on year) (exams included) Fall semester: 01 October – mid February Spring semester: mid-February – 30 June Deadlines for applications: Fall semester and whole academic year: 15 May Spring semester: 15 November Admission website (online registration compulsory) https://irk.uw.edu.pl/en-gb/home/ Fall semester: last week of September (exact dates may Orientation week differ from year on year) Spring semester: first week of semester First cycle – Bachelor level (3 years) Second cycle – Master level (2 years; 5 years only