Letter from Fofnc President, Ron Eggleston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Blocked Titles - Academic and Public Library Markets Factiva

Blocked Titles - Academic and Public Library Markets Factiva Source Name Source Code Aberdeen American News ABAM Advocate ADVO Akron Beacon Journal AKBJ Alexandria Daily Town Talk ADTT Allentown Morning Call XALL Argus Leader ARGL Asbury Park Press ASPK Asheville Citizen-Times ASHC Baltimore Sun BSUN Battle Creek Enquirer BATL Baxter County Newspapers BAXT Belleville News-Democrat BLND Bellingham Herald XBEL Brandenton Herald BRDH Bucryus Telegraph Forum BTF Burlington Free Press BRFP Centre Daily Times CDPA Charlotte Observer CLTO Chicago Tribune TRIB Chilicothe Gazette CGOH Chronicle-Tribune CHRT Cincinnati Enquirer CINC Clarion-Ledger (Jackson, MS) CLDG Cochocton Tribune CTOH Columbus Ledger-Enquirer CLEN Contra Costa Times CCT Courier-News XCNW Courier-Post CPST Daily Ledger DLIN Daily News Leader DNLE Daily Press DAIL Daily Record DRNJ Daily Times DTMD Daily Times Adviser DTA Daily World DWLA Democrat & Chronicle (Rochester, NY) DMCR Des Moines Register DMRG Detroit Free Press DFP Detroit News DTNS Duluth News-Tribune DNTR El Paso Times ELPS Florida Today FLTY Fort Collins Coloradoan XFTC Fort Wayne News Sentinel FWNS Fort Worth Star-Telegram FWST Grand Forks Herald XGFH Great Falls Tribune GFTR Green Bay Press-Gazette GBPG Greenville News (SC) GNVL Hartford Courant HFCT Harvard Business Review HRB Harvard Management Update HMU Hattiesburg American HATB Herald Times Reporter HTR Home News Tribune HMTR Honolulu Advertiser XHAD Idaho Statesman BSID Iowa City Press-Citizen PCIA Journal & Courier XJOC Journal-News JNWP Kansas City Star -

Newspaper Distribution List

Newspaper Distribution List The following is a list of the key newspaper distribution points covering our Integrated Media Pro and Mass Media Visibility distribution package. Abbeville Herald Little Elm Journal Abbeville Meridional Little Falls Evening Times Aberdeen Times Littleton Courier Abilene Reflector Chronicle Littleton Observer Abilene Reporter News Livermore Independent Abingdon Argus-Sentinel Livingston County Daily Press & Argus Abington Mariner Livingston Parish News Ackley World Journal Livonia Observer Action Detroit Llano County Journal Acton Beacon Llano News Ada Herald Lock Haven Express Adair News Locust Weekly Post Adair Progress Lodi News Sentinel Adams County Free Press Logan Banner Adams County Record Logan Daily News Addison County Independent Logan Herald Journal Adelante Valle Logan Herald-Observer Adirondack Daily Enterprise Logan Republican Adrian Daily Telegram London Sentinel Echo Adrian Journal Lone Peak Lookout Advance of Bucks County Lone Tree Reporter Advance Yeoman Long Island Business News Advertiser News Long Island Press African American News and Issues Long Prairie Leader Afton Star Enterprise Longmont Daily Times Call Ahora News Reno Longview News Journal Ahwatukee Foothills News Lonoke Democrat Aiken Standard Loomis News Aim Jefferson Lorain Morning Journal Aim Sussex County Los Alamos Monitor Ajo Copper News Los Altos Town Crier Akron Beacon Journal Los Angeles Business Journal Akron Bugle Los Angeles Downtown News Akron News Reporter Los Angeles Loyolan Page | 1 Al Dia de Dallas Los Angeles Times -

![Curriculum Vitae [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6002/curriculum-vitae-pdf-1726002.webp)

Curriculum Vitae [PDF]

October 23, 2020 ALICE JO RAINVILLE, PhD, RD, CHE, SNS, FAND [email protected] EDUCATION Degrees University of Texas Houston Health Science Center, School of Public Health, Ph.D. in Community Health Sciences, December, 1996. Discipline: Biological Sciences. Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois, Master of Science in Home Economics, August, 1981. Concentration: Foods and Nutrition. University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, Bachelor of Science in Human Resources and Family Studies, May, 1979. Major: Institution Management. Credentials and Certification Fellow, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Registered Dietitian, Commission on Dietetic Registration, 708395 Certified Hospitality Educator, Educational Institute of American Hotel and Motel Association School Nutrition Specialist, School Nutrition Association WORK EXPERIENCE AS UNIVERSITY FACULTY August, 1997 to present Eastern Michigan University Professor with Tenure teaching undergraduate and graduate courses on campus and online Human Nutrition and Dietetics Programs Currently Graduate Coordinator of M.S. in Human Nutrition Program September, 1989 to August, 1997 University of Texas Houston Health Science Center, School of Public Health and School of Allied Health Instructor, Faculty Associate, and Assistant Professor, Admissions Chair September, 1982-1984 North Harris County College, Houston, Texas Part-time Instructor, Continuing Education August, 1981 to December, 1981 Illinois State University, Home Economics Department, Normal, Illinois Lecturer 1 WORK -

Appendix G Media List for STIP Press Release

2008-2011 State Transportation Improvement Program Page 64 Appendix G Media Outlets (Numbers in parenthesis indicate the number of contacts within the media outlet that received the press release.) AAA Michigan (3) CITO-TV Albion Recorder City Pulse Alcona County Review Clare County Review Alegria Latina CMU Public Broadcasting Network Allegan County News (2) Coldwater Reporter Allegan County News/Union Enterprise Commercial Express-Vicksburg Alma Latina Radio Connection, The Ann Arbor News (4) Courier-Leader-Paw-Paw Antrim County News Crain's Detroit Business Arab American News Crawford County Avalanche Argus-Press Daily Globe Associated Press (2) Daily Press Bailey, John Daily Reporter Battle Creek Enquirer (4) Daily Telegram (2) Bay City Times (2) Daily Tribune (2) Beattie, Dan Detroit Free Press (3) Benzie County Record Patriot Detroit News (4) Berrien County Record Dowagiac Daily News Berrien Springs Journal-Era Ecorse Telegram Blade El Tiempo Boers, Dan El Vocero Hispano Bowman, Joan Elkhart Truth (6) Building Tradesman Evening News Bureau of National Affairs Flint Journal Burton News Fordyce, Jim Business Direct Weekly Fox 47 C & G Newspapers Frankenmuth News Cadillac News Fremont Times-Indicator Caribe Serenade Gladwin County Record & Beaverton Clarion Carson City Gazette Gongwer News Service Cass City Chronicle Grand Haven Tribune Cassopolis Vigilant/Edwardsburg Argus Grand Rapids Business Journal (3) Catholic Connector Grand Rapids Press (8) Charlevoix Courier Graphic CHAS-FM Hamtramck Citizen Cheboygan Daily Tribune Harbor Beach -

Blankenship Is a ENDURANCE and a PASSION for Competitive Person

MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training five years of exploration TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Introduction 5 Letter from the Principal Investigator 6 About MSU BEST 8 Guest Speakers 9 Accomplishments 12 Externships 15 Profiles 82 Trainees 84 Acknowledgments 87 Reflection An experimental program dedicated to empowering biomedical trainees to develop professional skills and experiences. At the root of our field is curiosity. 3 As scientists, we have an innate For five years, we’ve empowered desire to explore. We question the graduate students and postdoctoral norm. We pioneer new terrain. scholars to explore new paths We fail fast and fail often but, across a number of sectors: at the end of the day, we come innovation, legal, regulatory out with a solution backed by government, public affairs empirical truths. and academe. We aim to lead trainees to careers that are both So it’s only natural that we’d be personally and professionally drawn to the unending horizon meaningful, with potential to spark of diverse career opportunities— widespread change. and here at MSU Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training Now more than ever, it’s important (BEST), we give students to go forth and apply our research opportunities to do just that. from the lab to real-world contexts, and share our inventive Research in the lab is critical. But minds. Here’s to five more years it’s those real-world experiences— of embracing curiosity. Rolling connecting with professional up our sleeves. Shifting mindsets. partners, helping communities live Exploring. healthier or safer lives, inspiring the next generation of innovators—that help make a scientist the best they can be. -

Newsletter JUNIOR LEAGUE of LANSING 2012 Kids in the Kitchen Event a Success! Karissa Chabot-Purchase

JULY 2012 Focus Newsletter JUNIOR LEAGUE OF LANSING 2012 Kids in the Kitchen Event a Success! Karissa Chabot-Purchase he Junior League of Lansing’s 2011-12 New Member class Finally, we were thrilled to welcome Todd ‘TJ’ Duckett as our special guest. was proud to host an extremely successful seventh annual Duckett, a Michigan native, was the lead running back for MSU from 1999-2001 ‘Kids in the Kitchen’ event this April. and played in the NFL from 2002-2009. Now back in East Lansing, Duckett is passionately focused on working to better the community. He spoke to For the first time ever, the JLL partnered with Lansing Westside’s YMCA during participants about the importance of making responsible life choices, helped Ttheir national ‘Healthy Kids Day’ to deliver an exciting set of free health education raffle off a wide array of giveaways, and helped arrange for donation of our extra services to the nearly 300 children and families food items to a local children’s school. who participated in the day’s event (which was free and open to the public). Each year, Healthy Kids The 2011-2012 New Member class would like to extend Day encourages children and families to commit a special thank you to the following JLL Members who to nurturing an active body and mind by providing volunteered their time and talents before, during, and after opportunities for free health screenings, interaction KITK to make the event so successful: Christina Carr, with trainers, and exercise programming. The JLL Alexis Derrossett, Jennifer Edmonds, Yvonne Fleener, expanded upon the event tremendously by offering Susan Lupo, Becky Paalman, Kate Powers, Torye attendees the chance to put together nutritious snacks Santucci, Meghan Sifuentes, Betsy Svanda, (yogurt parfaits, vegetables with hummus, trail mix, Sarah Triplett, and Ann Vogelsang. -

Stanley Hollander Papers UA.17.287

Stanley Hollander Papers UA.17.287 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on April 02, 2019. Finding aid written in . Describing Archives: A Content Standard Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collections Conrad Hall 943 Conrad Road, Room 101 East Lansing , MI 48824 [email protected] URL: http://archives.msu.edu/ Stanley Hollander Papers UA.17.287 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Electronic Resources ................................................................................................................................... 5 - Page 2 - Stanley Hollander Papers UA.17.287 Summary Information Repository: -

KEVIN WALL SAUNDERS Michigan State University College of Law East Lansing, MI 48824-1300 (517) 432-6911 [email protected]

KEVIN WALL SAUNDERS Michigan State University College of Law East Lansing, MI 48824-1300 (517) 432-6911 [email protected] EDUCATION: J.D. University of Michigan, Magna Cum Laude (1984). Order of the Coif. Articles Editor, Michigan Law Review. Ph.D. (Philosophy) University of Miami (1978). Dissertation Title: A Method for the Construction of Modal Probability Logics. M.A. (Philosophy) University of Miami (1976). M.S. (Mathematics) University of Miami (1970). A.B. (Mathematics) Franklin and Marshall College (1968). EMPLOYMENT/ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS: Current Charles Clarke Chair in Constitutional Law, Michigan State University (2010- ); Acting Dean (October, 2006-February, 2007); Senior Associate Dean for Academic Affairs (2006-07), Professor of Law (2002- ), Visiting Professor of Law (2001-02). Courses taught: Constitutional Law I & II, First Amendment, Free Expression Seminar, Comparative Free Expression Seminar, Constitutional Theory Seminar, Jurisprudence, Criminal Law. Director of the King Scholars (Honors) Program, Adjunct Professor, Department of Communications, Fellow of the Quello Center for Telecommunications Management & Law. Visiting Scholar, Wolfson College and the Centre for Socio-Legal Studies, University of Oxford, Hillary Term (January-March), 2008. 1986-2002 Professor of Law, University of Oklahoma (Asst. Prof., 1986-88, Assoc. Prof., 1988-91, Prof. since 1991). On leave 1997-98, 2001-02. Courses taught: Constitutional Law, First Amendment, Constitutional Theory Seminar, Free Speech Seminar, Jurisprudence, Criminal Law, Criminal Procedure, Logic and Expert Systems Seminar, Federal Criminal Law, Corporate Criminal Liability, and Professional Ethics. Member of the Graduate Faculty, College of Liberal Studies Faculty, and Film and Video Studies Faculty. 1997-98 Visiting James Madison Chair in Constitutional Law and Acting Director of the Constitutional Law Resource Center, Drake University Law School. -

Best Use of Newspaper Art Service

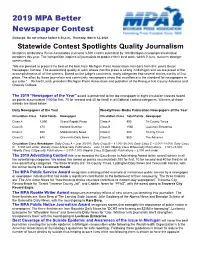

2019 MPA Better Newspaper Contest Embargo: Do not release before 6:30 p.m., Thursday, March 12, 2020 Statewide Contest Spotlights Quality Journalism Members of Montana Press Association reviewed 3,500 entries submitted by 106 Michigan newspapers/Individual members this year. The competition inspires all journalists to produce their best work, which in turn, nurtures stronger communities. “We are pleased to present the best of the best from Michigan Press Association members from this year's Better Newspaper Contest. The outstanding quality of work shows that the press is strong in Michigan and we are proud of the accomplishments of all the winners. Based on the judge’s comments, many categories had several entries worthy of first place. The effort by these journalists and community newspapers show that excellence is the standard for newspapers in our state.” —Richard Lamb, president Michigan Press Association and publisher of the Presque Isle County Advance and Onaway Outlook. The 2019 “Newspaper of the Year” award is presented to the top newspaper in eight circulation classes based on points accumulated (100 for first, 70 for second and 40 for third) in all Editorial contest categories. Winners of those awards are listed below. Daily Newspapers of the Year Weekly/News Media Publication Newspapers of the Year Circulation Class Total Points Newspaper Circulation Class Total Points Newspaper Class A 1,090 Grand Rapids Press Class A 990 Tri-County Times Class B 670 Holland Sentinel Class B 1580 Leelanau Enterprise Class C 940 Midland Daily News Class C 900 Tri-City Times Class D 840 Greenville Daily News Class D 950 The Advance Circulation Class Breakdown: Daily Class A – over 20,000; Daily Class B – 11,001-20,000; Daily Class C – 5,001-11,000; Daily Class D – 5,000 and under; Weekly Class A/Specialty Publications – over 15,000; Weekly Class B/Specialty Publications – 7,001-15,000; Weekly Class C/Specialty Publications – 3,001-7,000; Weekly Class D/Specialty Publications – 3,000 and under. -

State of Michigan Before the Michigan Public Service

STATE OF MICHIGAN BEFORE THE MICHIGAN PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION In the Matter of the Application of ) DTE ELECTRIC COMPANY for ) Reconciliation of its Transitional ) Reconciliation Mechanism associated with the ) Case No. U-18005 Disposition of the City of Detroit Public ) Lighting System for the Period of ) January 1, 2015 through December 31, 2015 ) AFFIDAVITS OF PUBLICATION Ann Arbor News 5/19/2016 Bay City Times 5/19/2016 Daily Tribune – Royal Oak 5/19/2016 Detroit Free Press 5/18/2016 Detroit News 5/18/2016 Flint Journal 5/19/2016 Huron Daily Tribune 5/20/2016 Lansing State Journal 5/19/2016 Macomb Daily – Mt. Clemens 5/19/2016 Monroe Evening News 5/19/2016 Oakland Press – Pontiac 5/19/2016 Port Huron Times Herald 5/19/2016 Saginaw News 5/19/2016 A6 / THURSDAY, MAY 19, 2016 / THE ANN ARBOR NEWS Local ANN ARBOR ANN ARBOR Police 229 Main Street apartments get initial approval ID fugitive By Ryan Stanton public use, as well as two [email protected] Zipcar spaces for exclusiVe who killed For a while Tuesday use by tenants. night, it was uncertain Brandt Stiles, a repre- whether a new apart- sentatiVe of Collegiate himself ment building proposed DeVelopment Group, said for South Main Street there will be a public bike- By Darcie Moran had enough Votes to get share program. [email protected] the Ann Arbor Planning The new deVelopment Police haVe identified Commission’s blessing. would include 6,200 the fugitiVe who shot and “It’s a tossup right square feet of ground- killed himself at an Ann now,” Commissioner Ken floor retail space, so there Arbor apartment complex Clein said more than an would be no loss of neigh- last week. -

2012 Better Newspaper Contest Awards

EMBARGO: Do not release before 12:01 a.m., Sunday, October 7, 2012. 2012 Better Newspaper Contest Awards Members of North Carolina Press Association reviewed 2,776 entries submitted by 109 Michigan newspapers when they judged the 2012 Michigan Press Association Better Newspaper Contest. Judges’ decisions and comments are listed on the following pages. Complete results are available online at www.michiganpress.org. The 2012 “Newspaper of the Year” award is presented to the top newspaper in eight circulation classes based on points accumulated (100 for first, 70 for second and 40 for third – points are doubled in the General Excellence contest) in all Editorial contest categories. Winners of those awards are listed below. Daily Newspapers of the Year Weekly Newspapers of the Year Circulation Total Circulation Total Class Points Newspaper Class Points Newspaper Class A 2060 Detroit Free Press Class A 850 The News-Herald Class B 2580 Lansing State Journal Class B 860 Tri-County Times Class C 3160 Traverse City Record-Eagle Class C 1000 Leelanau Enterprise Class D 500 Livingston County Daily Press & Argus Class D 1320 State Line Observer Circulation Class Breakdown: Daily Class A – 70,000 or more; Daily Class B – 30,000-69,999; Daily Class C – 15,000-29,999; Daily Class D – under 15,000; Weekly Class A – 25,000 or more; Weekly Class B – 10,000 – 24,999; Weekly Class C – 4,000-9,999; Weekly Class D – under 4,000. The MPA Public Service Award recognizes a distinguished example of meritorious public service by a newspaper or newspaper individual that has made a significant contribution to the betterment of their community.