Socio-Cultural Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Week Workshop on Recent Advances in Engineering Science

About INAE About NIT, Sikkim One Week Workshop The Indian National Academy of Engineering (INAE), National Institute of Technology Sikkim, an institute of founded in 1987 comprises India’s most distinguished national importance is one among the ten newly sanctioned engineers, engineer-scientists and technologists covering the on NIT(s) by the Government of India in 2009. The institute is entire spectrum of engineering disciplines. INAE functions as offering B. Tech programs in Computer Science and Engineering, an apex body and promotes the practice of engineering & Electronics and Communication Engineering, Electrical and Recent Advances in technology and the related sciences for their application to Electronics Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, and Civil solving problems of national importance. The Academy also Engineering Engineering. Moreover, the institute offers M.Tech programs in provides a forum for futuristic planning for country’s Microelectronics & VLSI Design, Electrical and Electronics Science and Technology development requiring engineering and technological inputs Engineering, and Computer Science Engineering. The Institute and brings together specialists from such fields as may be also offers M Sc. program in Chemistry and Ph. D program in all necessary for comprehensive solutions to the needs of the ST th departments. (March 1 –to-05 , 2020) country. The Dept. of ECE offers research in the areas of ASIC & Modeling Jointly organized by and Optimization of High Performance Semiconductor Devices, Background Microwave Engineering & Antenna Design, Wireless The current research in Electronics and Communication National Institute of Technology Communication, Signal Processing, Satellite Communication and Engineering has emerged as a very important technology in Navigation. The Dept. has good laboratory facility with modern modern electronics featuring deep sub-micron manufacturing Sikkim equipment to encourage the students to cope up with the latest processes, low voltage operations, exploding speeds and smart (Sponsored by TEQIP-III) technologies. -

Rapid Biodiversity Survey Report-I 1

RAPID BIODIVERSITY SURVEY REPORt-I 1 RAPID BIODIVERSITY SURVEY REPORT - I Bistorta vaccinifolia Sikkim Biodiversity Conservation and Forest Management Project (SBFP) Forest, Environment and Wildlife Management Department Government of Sikkim Rhododendron barbatum Published by : Sikkim Biodiversity Conservation and Forest Management Project (SBFP) Department of Forests, Environment and Wildlife Management, Government of Sikkim, Deorali, Gangtok - 737102, Sikkim, India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Department of Forest, Environment and Wildlife Management, Government of Sikkim, Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Project Director, Sikkim Biodiversity Conservation and Forest Management Project, Department of Forests, Environment and Wildlife Management, Government of Sikkim. 2 RAPID BIODIVERSITY SURVEY REPORt-I Contents Page No. 5 Message 6 Forward 7 Preface 8 Acknowledgement 9 Introduction 12 Rapid Biodiversity Survey. 14 Methodology 16 Sang - Tinjurey sampling path in Fambonglho Wildlife Sanctuary, East Sikkim. 24 Yuksom - Dzongri - Gochela sampling path of Kanchendzonga Biosphere reserve, West Sikkim 41 Ravangla - Bhaleydunga sampling path, Maenam Wildlife Sanctuary, South Sikkim. 51 Tholoung - Kishong sampling path, Kanchendzonga National Park, North Sikkim. -

Government of Sikkim Baluwakhani, Gangtok – 737101

SIKKIM GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRA ORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY GANGTOK FRIDAY 22nd OCTOBER 2010 No. 579 DIRECTORATE OF SIKKIM STATE LOTTERIES FINANCE, REVENUE & EXPENDITURE DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM BALUWAKHANI, GANGTOK – 737101 No. FIN/DSSL/ RESULTS/ 36 Dated: 20th October 2010 NOTIFICATION The Daily Lottery Results from 01st October 2010 to 10th October 2010(no draws were held on 2nd October 2010 being a National Holiday) of the following weekly lottery schemes of the Sikkim State Lotteries marketed through the Distributor, M/S Future Gaming Solutions Pvt. Ltd. are hereby notified for general information as per Annexures 1 to 9 :- 1. Swarnalakshmi set a weekly lotteries (Monday to Sunday) 2. Singtam Evening set of weekly (Monday to Sunday) 3. Dear Evening set of weekly lotteries (Monday to Sunday) The Daily Lottery Results from 11th September 2010 to 15th September 2010 of the following weekly lottery schemes of the Sikkim State Lotteries marketed through the Distributor, M/S/ Future Gaming Solutions India Pvt. Ltd. Are hereby notified for general information as per Annexures 10 to 14:- 1. Singtam Evening set of weekly lotteries (Monday to Sunday) 2. Dear Evening set of lotteries (Monday to Sunday) By Order. Director, Sikkim State Lotteries SIKKIM GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRA ORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY GANGTOK MONDAY 25TH OCTOBER 2010 No. 580 GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM LAND REVENUE & DISASTER MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT NOTIFICATION NO:173/827/LR&DMD(S) DATED:14/10/2010. NOTICE UNDER SECTION 4(1) OF LAND ACQUISITION ACT, 1894 (ACT I OF 1894) Whereas it appears to the Governor that additional land is likely to be needed for the public purpose, not being a purpose of the Union, namely for the construction of Hydel Project by S.P.D.C Ltd. -

The Chief Minister of Sikkim Mr. Pawan Cham of the Bhairon Singh

The Chief Minister Of Sikkim Mr. Pawan Chamling is the first r of the Bhairon Singh Shekhawat Lifetime Achiev Service 28 june.indd 1 10/08/17 5:07 pm er Of Sikkim Mr. Pawan Chamling is the first recipient on Singh Shekhawat Lifetime Achievement Award in Public Service 28 june.indd 2 10/08/17 5:07 pm 28 june.indd 3 10/08/17 5:07 pm Printed By: The Prism, © Khangchendzonga Falls, West Sikkim by, Aita bdr. Gurung Deorali, Gangtok 28 june.indd 4 10/08/17 5:07 pm From The Editor’s Desk he second issue of Sikkim Today is a testimony of the continued combined effort of our team at the Information and Public TRelations Department. Therefore, it ills me with delight and gratiication both in bringing out this issue. The focus of the magazine for this month is the environment and the natural marvels that Sikkim has been abundantly blessed with. It is a serious and a signiicant topic because there is an absolute need for everyone to fathom how every action and activity of ours has a direct impact on the environment. We need to acknowledge and accept that the damage that we cause to nature is a damage we cause to ourselves. The month of June is especially signiicant for a biodiversity rich State like Sikkim, as numerous environment sustaining activities conceptualized by our environmentally cognizant Hon’ble Chief Minister, Mr. Pawan Chamling, is held and actively participated in by the people of the State. Sikkim, guided by the Hon’ble Chief Minister is becoming both clairvoyant and cautious. -

Government Initiatives on Environment

Chapter 11 GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES ON ENVIRONMENT STATE GREEN MISSION A Unique Innovative Environment Programme Launched in Sikkim The Government of Sikkim launched a Sikkim being a Green State. The Hon’ble Chief unique and innovative programme called “State Green Minister Dr. Pawan Chamling formally launched this Mission” with the view to raise avenue plantation along Mission on 27th February 2006 in the presence of all the roads and beautification of all vacant and waste Ministers, officers and the public of Sikkim. lands to further reinforce wide spread recognition of Launching of Sikkim Green Mission on 27th February 2006 Aims and Objectives The major objectives of the programme are to The greenery generated out of this programme will create green belt and avenues for meeting aesthetic also reduce noise pollution to the neighboring recreational needs of the people and beautify the areas household population; attract the avifauna, butterflies, for tourist attraction. This programme is expected to squirrels etc and their shelter. Sikkim becoming a provide fringe benefits like reduction in the surface run- Garden State, the mission will also work with objective off discharge and checking erosion in the downhill side to promote tourism as a sustainable and eco friendly and will also create a store house of genetic diversity by activity in the state of Sikkim. The programme is also planting all the indigenous trees, shrubs, herbs, expected to generate awareness on environment & climbers, creepers, conifers and green foliages forests and bringing in sense of participation and including fruits and medicinal plants. ownership among people in the whole process. Implementing Mechanism A State level committee under the chairmanship officer for each constituency. -

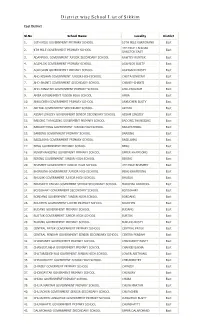

District Wise School List of Sikkim

District wise School List of Sikkim East District Sl.No School Name Locality District 1. 10TH MILE GOVERNMENT PRYMARY SCHOOL 10TH MILE KARPONANG East 4TH MILE J.N ROAD 2. 4TH MILE GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL East GANGTOK EAST 3. ADAMPOOL GOVERNMENT JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL RAWTEY-RUMTEK East 4. AGAMLOK GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL AGAMLOK BUSTY East 5. AGRIGAON GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL AGRIGAON BUSTY East 6. AHO-KISHAN GOVERNMENT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL CHOTA-SINGTAM East 7. AHO-SHANTI GOVERNMENT SECONDARY SCHOOL CHANEY-SHANTI East 8. AHO-YANGTAM GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL AHO-YANGTAM East 9. AMBA GOVERNMENT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL AMBA East 10. ANKUCHEN GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL ANKUCHEN BUSTY East 11. ARITAR GOVERNMENT SECONDARY SCHOOL ARITAR East 12. ASSAM LINGZEY GOVERNMENT SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL ASSAM LINGZEY East 13. BADONG THANGSING GOVERMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL BADONG THANGSING East 14. BARAPATHING GOVERNMENT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL BARAPATHING East 15. BARBING GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL BARBING East 16. BASILAKHA GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL BASILAKHA East 17. BENG GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL BENG East 18. BENGTHANGSING GOVERMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL UPPER KHAMDONG East 19. BERING GOVERNMENT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL BERING East 20. BHASMEY GOVERNMENT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL 4TH MILE BHASMEY East 21. BHIRKUNA GOVERNMENT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL BENG KHAMDONG East 22. BHUSUK GOVERNMENT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL BHUSUK East 23. BIRASPATI PARSAI GOVERMENT SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL MARCHAK RANIPOOL East 24. BOJOGHARI GOVERNMENT SECONDARY SCHOOL BOJOGHARI East 25. BORDANG GOVERNMENT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL BORDANG East 26. BOUCHEN GOVERNMENT LOWER PRIMARY SCHOOL BOUCHEN East 27. BUDANG GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL BUDANG East 28. BURTUK GOVERNMENT JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL BURTUK East 29. BURUNG GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOL BURUNG BUSTY East 30. -

Sikkim Government Gazette Extraordinary Number 56 Dated the 28 Th April 1997

SIKKIM GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRA ORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Gangtok, Friday, 7 th January , 2005 No. 1 LABOUR DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM GANGTOK No.17/DL Dated: 6/01/2005. NOTIFICATION The draft of the Sikkim Minimum Wages Rules, 2004 which the State Government proposes to issue in exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) of Section 30 of the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, ( 11 of 1948 ), is hereby published as required under sub- Section (1) of Section 30 of the said Act for information of all persons likely to be affected thereby and notice is hereby given that the said draft rules would be taken into consideration after expiry of a period of 45 (forty five) days from the date on which the notification is published in the Official Gazette. Any objections or suggestions which may be received from any person with respect to the said draft before the expiry of the period so specified will be considered by the State Government. DRAFT RULES Short title and 1. (1) These rules may be called the Sikkim Minimum Wages Rules,2004. commencement (2) They shall be deemed to have come into force on the 1st day of October, 2004 Definition 2. In these rules, unless the context otherwise requires,— (1) (a) “ Act” means the Minimum Wages Act, 1948; (b) “ Authority” means the authority appointed under sub- section (1) of section 20; (c) “ Board” means the Advisory Board appointed under section 7; (d) “ Chairman” means the Chairman of the Advisory Board or the Committee, as the case may be, appointed under section 9; (e) “ Committee” means a Committee appointed under clause (a) of sub- section (1) of section 5 and includes a Sub- committee appointed under that section; (f) “ form “ means a form appended to these rules; (g) “ Inspector” means a person appointed as Inspector under section 19; (h) “ Section” means a section of the Act; (2) All other words and expressions used herein and not defined shall have the meanings respectively assigned to them under the Act. -

Aaron Marketing Services Pvt Ltd

+91-9007638888 Aaron Marketing Services Pvt Ltd https://www.indiamart.com/aaron-group-kolkata/ Brief History on Sikkim Not much is known about Sikkim's ancient history, except for the fact that the first inhabitants were the Lepchas or Rong (ravine folk). Lepchas are said to have come from to the region from the Assam and Myanmar ... About Us Brief History on Sikkim Not much is known about Sikkim's ancient history, except for the fact that the first inhabitants were the Lepchas or Rong (ravine folk). Lepchas are said to have come from to the region from the Assam and Myanmar side. During 1200 AD Sikkim was absorbed by other clans from Tibet which included the Namgyal clan, who arrived in the 1400's and steadily won political control over Sikkim. In 1642, Phuntsog Namgyal (1604-1670) became the Chogyal (king). He presided over a social system based on Tibetan Lamaistic Buddhism. His descendants of Phuntsog Namgyal ruled Sikkim for more than 330 years. During the 1700's, Sikkim suffered continuous attacks from Nepal and Bhutan, after which it lost much of its territory. Nepalese also came to Sikkim and settled there as farmers. By the 1800's, Sikkim's population was culturally very complicated, and internal conflict resulted. In 1814-1815, Sikkim backed the British in a successful war against Nepal, and won back some of its territory, once lost. In 1835, the British East India Company acquired the health resort of Darjeeling from Sikkim. During the mid-1800's, Sikkim violently withstand attempts to bring it under British rule, but in 1861 it finally became a British colony. -

Sikkim 2016 648422

648422 DRA TF SIKKIM 2016 648422 State of Environment Report Sikkim 2016 Message from Honourable Chief Minister iii Message from Honourable Chief Minister iii Message from Honourable Minister of Forest v Message from Honourable Minister of Forest v Foreword Principal Secretary-PCCF Rhododendron forest along Tholung – Kishong Trail vii Foreword Principal Secretary-PCCF Rhododendron forest along Tholung – Kishong Trail vii Preface ENVIS Coordinator R. mekongense var. mekongense ix Preface ENVIS Coordinator R. mekongense var. mekongense ix Acknowledgement ENVIS SIKKIM, Sikkim Forest Department xi Acknowledgement ENVIS SIKKIM, Sikkim Forest Department xi Glossary of Terms Agricultural Labourers: A person who works on another person's land for wages in cash or kind or share is regarded as an agricultural labourer. She or he has no risk in the cultivation, but merely works on another person's land for wages. An agricultural labourer has no right of lease or contract on land on which she/he works. Biodiversity: Is the term given to the variety of life on Earth. It is the variety within and between all species of plants, animals and microorganisms and the ecosystems within which they live and interact. Climate Change: A change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties, and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. Cultivator: A person is classified as cultivator if he or she is engaged in cultivation of land owned or held from Government or held from private persons or institutions for payment in money, kind or share. -

SIKKIM- DRAFT ANNUAL PLAN 1988-89-D04393.Pdf

S i l K K l i U - 54161 S O S J25- £ S I K C - D PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT C30VERNMENT OF SIKKIM GANGTOK : SIKKIM DRAFT ANNUAL PLAN 19^8 - 89 ._te ox ■ t- painist^ CONTENTS- It •k -k^-k-k 'k/k ★ * * i/-‘ No..- 1 1. INTRODUCTION AND S T A T E M E N T .... 2. AGRICULTURE AND ALLIED SERVrCES ; 6 Agriculture Research & Education/ .. Crop Husbandry, Storage & Ware 7 housing, Marketing .& Quality Contro 6^^ Soil Conse r\ration 25 00® 2 ©^0 Animal Husbandry & Dairy Dev'elopmen 30 Fisheries 38 01" Forest Sc Wild Life 43 Cooperation 54 00^ 3. RURAL DEVELOPMENT s , f IRDP, IREP, NREP, RLEGP, Community Development 65- C V Land Reforms 73 030 4. IRRIGATION AND FLOOD CONTROL s 76 0?5@ 81 5. ENERGY s v_- Power ^82 Non-Conventional Sources of Energy ^^93 0*0 6. INDUSTRY AND MINERALS ; "lOO Village & Small Scale Industries^ Medium Industries 104 .114 @S0 Mines and Geology @i§0 118 7. TRANSPORT s 0 10 Roads Sc Bridges 119 Road Transport including Helicopter Services 142 c o @0^ 8. SCIENCE^ TECHNOLOGY AND 000 ENVIRONMENT : 150 planri'-— ---- - V • • • ^ ‘ pOC. j3ENB.RA'L''EC0N0MIC s e r vic e s ; 159 Qate— S®^‘ '■ Secretariat Economic Services^ Weights and Measures and General 0®@ Services 159 see Tourism 167 Civil Supplies 173' 00* 000 10. e d u c a t i o n / SPORTS^ ART AND CULTURE s- 000 0@0 General Education, Sports and Youth 000 Welfare ,177 00® «0® Art and Culture 192 000 000 11. -

Tourism of Namchi, South District of Sikkim: an Overview

Science, Technology and Development ISSN : 0950-0707 TOURISM OF NAMCHI, SOUTH DISTRICT OF SIKKIM: AN OVERVIEW Amrita SardarPramanick Research Scholar, Dept. of. Geography, C.M.J. University, Jorabat, Meghalaya, India. Dr.Harsha Kumar Das Gupta Research Guide, Dept. of. Geography, C.M.J. University, Jorabat, Meghalaya, India. Abstract: Needless to say, Sikkim is a wonderful tourist destination of our country. South district of Sikkim is comparatively smaller than three other districts of this state. However, it has some of the most amazing places to visit. The nature lovers, adventurists, as well as the other tourists who are very much interested for angling, rafting, camping, trekking, wildlife exploration etc. find this South district as the most ideal destination for their complete enjoyment as it really acts as a healing agent. The present study deals with the infrastructure, scope and possibility of Namchi as the main tourist focus of South Sikkim. This area has the high natural potential of being an excellent tourist attraction of South Sikkim. But in the field of tourism over grooming is taking place because of the huge investment of private business houses and religious trust foundation. Keywords: tourist destination, trekking, rafting, tourism infrastructure. Introduction In terms of Gross Domestic Product, tourism is the second largest contributory sector in Sikkim. This state provides a wide potential in tourism that has yet largely remained unexploited. The perennially snow-capped mountains, lush green tropical and temperate forests, gurgling streams and the rich flora and fauna are all present there for the tourists to savor. The State Government aims at promoting sustainable tourism and simultaneously encourages the private sectors to develop tourism related infrastructure and services without disturbing ecology and environment and also to reduce the tourist pressure at Gangtok, the capital city of Sikkim.