Prepared for the CBB by Peter A. Thompson1, July 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drugs, Guns and Gangs’: Case Studies on Pacific States and How They Deploy NZ Media Regulators

‘BACK TO THE SOURCE’ 7. ‘Drugs, guns and gangs’: Case studies on Pacific states and how they deploy NZ media regulators ABSTRACT Media freedom and the capacity for investigative journalism have been steadily eroded in the South Pacific in the past five years in the wake of an entrenched coup and censorship in Fiji. The muzzling of the Fiji press, for decades one of the Pacific’s media trendsetters, has led to the emergence of a culture of self-censorship and a trend in some Pacific countries to harness New Zealand’s regulatory and self-regulatory media mechanisms to stifle unflattering reportage. The regulatory Broadcasting Standards Authority (BSA) and the self-regulatory NZ Press Council have made a total of four adjudications on complaints by both the Fiji military-backed regime and the Samoan government and in one case a NZ cabinet minister. The complaints have been twice against Fairfax New Zealand media—targeting a prominent regional print journalist with the first complaint in March 2008—and twice against television journalists, one of them against the highly rated current affairs programme Campbell Live. One complaint, over the reporting of Fiji, was made by NZ’s Rugby World Cup Minister. All but one of the complaints have been upheld by the regulatory/self-regulatory bodies. The one unsuccessful complaint is currently the subject of a High Court appeal by the Samoan Attorney-General’s Office and is over a television report that won the journalists concerned an investigative journalism award. This article examines case studies around this growing trend and explores the strategic impact on regional media and investigative journalism. -

Research in the Spotlight What Am I Discovering?

RESEARCH IN THE SPOTLIGHT WHAT AM I DISCOVERING? side of the world to measure the effects of poi on UNINEWS highlights some of the University physical and cognitive function in a clinical trial. research milestones that have hit the I wanted to discover how science and culture headlines in the past couple of months. might meet, and what they might say to each other about a weight orbiting on the end of a FISHING string. A study that exposed six decades of Working between the Centre for Brain widespread under reporting and dumping of Research and Dance Studies, the first round of marine fish has been covered extensively in an assessor-blind randomised control trial has the media. Lead researcher Dr Glenn Simmons just concluded. Forty healthy adults over 60 from the New Zealand Asia Institute at the years old participated in a month of International Business School appeared on Nine To Noon, Poi lessons (treatment group) or Tai Chi lessons Paul Henry, Radio Live, NewsHub and One (control group), and underwent a series of News, and was quoted in print and online. The pre- and post-tests measuring things like research, part of a decade-long, international balance, upper limb range of motion, bimanual project to assess the total global marine catch, coordination, grip strength, and cognitive put the true New Zealand catch at 2.7 times flexibility. Feedback from the participants official figures. after their International Poi lessons has been exciting: “Positive on flexibility, stress release, coordination and concentration. Totally, totally GRADUATION positive. Mental and physical.” “I am able to AGING GRACEFULLY use my left wrist more freely, and I am focusing The story of 84-year-old Nancy Keat, oldest better. -

Palmerston North Radio Stations

Palmerston North Radio Stations Frequency Station Location Format Whanganui (Bastia Hill) Mainstream Radio 87.6 FM and Palmerston rock(1990s- 2018 Hauraki North (Wharite) 2010s) Palmerston Full service iwi 89.8 FM Kia Ora FM Unknown Unknown North (Wharite) radio Palmerston Contemporary 2QQ, Q91 FM, 90.6 FM ZM 1980s North (Wharite) hits ZMFM Palmerston Christian 91.4 FM Rhema FM Unknown North (Wharite) contemporary Palmerston Adult 92.2 FM More FM 1986 2XS FM North (Wharite) contemporary Palmerston Contemporary 93.0 FM The Edge 1998 Country FM North (Wharite) Hit Radio Palmerston 93.8 FM Radio Live Talk Radio Unknown Radio Pacific North (Wharite) Palmerston 94.6 FM The Sound Classic Rock Unknown Solid Gold FM North (Wharite) Palmerston 95.4 FM The Rock Rock Unknown North (Wharite) Palmerston Hip Hop and 97.0 FM Mai FM Unknown North (Wharite) RnB Classic Hits Palmerston Adult 97.8 FM The Hits 1938 97.8 ZAFM, North (Wharite) contemporary 98FM, 2ZA Palmerston 98.6 FM The Breeze Easy listening 2006 Magic FM North (Wharite) Palmerston North Radio Stations Frequency Station Location Format Radio Palmerston 99.4 FM Campus radio Unknown Radio Massey Control North (Wharite) Palmerston 104.2 FM Magic Oldies 2014 Magic FM North (Wharite) Vision 100 Palmerston 105.0 FM Various radio Unknown Unknown FM North (Kahuterawa) Palmerston Pop music (60s- 105.8 FM Coast 2018 North (Kahuterawa) 1970s) 107.1 FM George FM Palmerston North Dance Music Community 2XS, Bright & Radio Easy, Classic 828 AM Trackside / Palmerston North TAB Unknown Hits, Magic, TAB The Breeze Access Triple Access Community Nine, 999 AM Palmerston North Unknown Manawatu radio Manawatu Sounz AM Pop Palmerston 1548 AM Mix music (1980s- 2005 North (Kahuterawa) 1990s) Palmerston North Radio Stations New Zealand Low Power FM Radio Station Database (Current List Settings) Broadcast Area: Palmerston North Order: Ascending ( A-Z ) Results: 5 Stations Listed. -

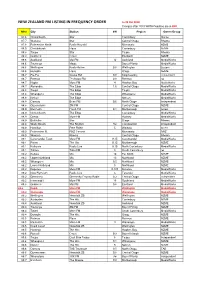

NZL FM Master List to Oct18

NEW ZEALAND FM LISTING IN FREQUENCY ORDER to 29 Oct 2018 Changes after 2019 WRTH Deadline are in RED MHz City Station kW Region Owner/Group 87.6 Christchurch Star Canterbury Rhema 87.7 Wanaka Star Central Otago Rhema 87.8 Palmerston North Radio Hauraki Manawatu NZME 88.0 Christchurch Flava Canterbury NZME 88.3 Taupo Star Taupo Rhema 88.3 Gisborne Coast Eastland NZME 88.6 Auckland Mai FM 10 Auckland MediaWorks 88.6 Tauranga Magic Bay of Plenty MediaWorks 88.6 Wellington Radio Active 0.5 Wellington Student 88.6 Dunedin Flava Otago NZME 88.7 Pio Pio Cruise FM 0.8 King Country Independent 88.7 Rotorua Te Arawa FM 0.8 Rotorua Iwi 88.7 Napier More FM 4 Hawkes Bay MediaWorks 88.7 Alexandra The Edge 1.6 Central Otago MediaWorks 88.8Taupo The Edge Taupo MediaWorks 88.8 Whanganui The Edge Whanganui MediaWorks 88.8 Nelson The Edge Nelson MediaWorks 88.8 Oamaru Brian FM 0.6 North Otago Independent 88.8 Queenstown ZM-FM Central Otago NZME 88.9 Blenheim Fresh FM 0.1 Marlborough Access 88.9 Christchurch The Edge Canterbury MediaWorks 88.9 Orewa More FM Rodney MediaWorks 88.9 Balclutha Star Otago Rhema 89.0 Waihi Beach The Rhythm 8w Coromandel Independent 89.0 Hamilton Free FM89 5 Waikato Access 89.0 Palmerston N. RNZ Concert Manawatu RNZ 89.0 Wanaka Rhema Central Otago Rhema 89.1 Coromandel Town More FM 0.15 Coromandel MediaWorks 89.1 Picton The Hits 0.15 Marlborough NZME 89.1 Kaikoura Radio Live 0.15 North Canterbury MediaWorks 89.1 Timaru Tahu FM 5 South Canterbury Iwi 89.2 Kaitaia Mix 10 Far North NZME 89.2 Upper Northland Mix 10 Northland NZME 89.2 -

BSA DECISIONS ISSUED SUMMARY for the Quarter July to September

BSA DECISIONS ISSUED SUMMARY for the Quarter July to September Upheld No. Complainant Broadcaster Programme Nature of the complaint Standards Finding 2008-036 Hammond TVNZ Eyes Wide Shut Movie containing sex scenes, language, drug use Children's interests Upheld 2008-032 Findlay TVNZ Rome Historical drama contained course language Good taste and decency Upheld 2007-138 LM TVNZ Skin Doctors Woman undergoing breast augmentation Privacy Upheld 2008-040 Pryde RNZ Nine to Noon Update on situation in Fiji Accuracy, balance Upheld (accuracy) 2008-066 Harrison TVNZ Ugly Betty Contained sexual themes Programme classification, Upheld promo children's interests, good (programme taste and decency classification and children's interests) 2008-039A Nudds TVNZ Wolf Creek Horror film with disturbing violence Violence, Children's Upheld (violence) interests, good taste and decency 2008-039B McIntosh TVNZ Wolf Creek Horror film with disturbing violence Violence, Children's Upheld (violence) interests, good taste and decency Not Upheld No. Complainant Broadcaster Programme Nature of the complaint Standards Finding 2008-041 Scott TVWorks Ltd 3 News Report that celebrity had obtained diversion for Privacy Not Upheld shoplifting 2008-030 Blazey TVWorks Ltd 3 News Item showed clothed body of dead teenager Good taste and decency Not Upheld 2008-017 South Pacific RadioWorks Radio Live Host disclosed address of house used in TV Privacy Not Upheld Pictures Ltd programme 2008-027 FitzPatrick TVNZ Close Up Discussion about ASA ruling Balance Not Upheld 2008-042 Clancy -

Damian Golfinopoulos

Damian Golfinopoulos. Phone: 021-023-95075 Email: [email protected] Website: damian.pictures Work History • News Video Editor at Mediaworks New Zealand • Freelance Sound Technician / Stage Management March 2013 - Present (3 years 6 months) 2006 - 2012 News and current affairs video editing for all of TV3/NewsHub News Corporate to mayhem - Ive done the lot. I have worked as a venue Programmes: Firstline, 12News, 6 O Clock, Nightline, Campbell Live, technician for Mainline Music (2006), The International Comedy Fes- The Nation, 360 and The Nation. tival (2007 /2008), Kings Arms, Bacco & Monte Cristo Room,Wham- my Bar, Wine Cellar, The Powerstation, Leigh Sawmill, DogsBollix, Big • Media Exchange Operator at Mediaworks New Zealand Day Out (2010) and more! I have worked with international perform- ers, bankers through to Tool Cover bands. March 2012 - Present (1 year 1 month) General ingest and data wrangling duties for TV3/NewsHub News. Honors and Awards • Director/Writer at Candlelit Pictures • The Sun Hates Me - Vimeo Staff Pick 2014 January 2013 - Present (3 years 8 months) • Show Me Shorts - Semi Finalist ‘Best Music Video’ I joined Candlelit Productions in 2013 to help edit and Direct ‘The Sun Hates Me’ which was staff picked on Vimeo and since then have gone through the Candlelit ‘Emerging Directors Program’ where I pitched for, and won 4 NZ On Air Music Video projects. From this ex- Education perience I have been lucky to work as a Director with many profes- sional film crews. Candlelit is currently helping me develop a short • AUT - 1 year Communications film to go into production. -

THE PACIFIC-ASIAN LOG January 2019 Introduction Copyright Notice Copyright 2001-2019 by Bruce Portzer

THE PACIFIC-ASIAN LOG January 2019 Introduction Copyright Notice Copyright 2001-2019 by Bruce Portzer. All rights reserved. This log may First issued in August 2001, The PAL lists all known medium wave not reproduced or redistributed in whole or in part in any form, except with broadcasting stations in southern and eastern Asia and the Pacific. It the expressed permission of the author. Contents may be used freely in covers an area extending as far west as Afghanistan and as far east as non-commercial publications and for personal use. Some of the material in Alaska, or roughly one half of the earth's surface! It now lists over 4000 this log was obtained from copyrighted sources and may require special stations in 60 countries, with frequencies, call signs, locations, power, clearance for anything other than personal use. networks, schedules, languages, formats, networks and other information. The log also includes longwave broadcasters, as well as medium wave beacons and weather stations in the region. Acknowledgements Since early 2005, there have been two versions of the Log: a downloadable pdf version and an interactive on-line version. My sources of information include DX publications, DX Clubs, E-bulletins, e- mail groups, web sites, and reports from individuals. Major online sources The pdf version is updated a few a year and is available at no cost. There include Arctic Radio Club, Australian Radio DX Club (ARDXC), British DX are two listings in the log, one sorted by frequency and the other by country. Club (BDXC), various Facebook pages, Global Tuners and KiwiSDR receivers, Hard Core DXing (HCDX), International Radio Club of America The on-line version is updated more often and allows the user to search by (IRCA), Medium Wave Circle (MWC), mediumwave.info (Ydun Ritz), New frequency, country, location, or station. -

Television Current Affairs Programmes on New Zealand Public Television

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AUT Scholarly Commons Death of a Genre? 1 The Death of a Genre?: Television Current Affairs Programmes on New Zealand Public Television Sarah Baker School of Communication Studies, Auckland University of Technology Abstract “We need the angry buzz of current affairs programmes” (Professor Sylvia Harvey in Holland, 2006, p. iv) “In a public system, television producers acquire money to make programmes. In a commercial system they make programmes to acquire money” (Tracey, 1998, p.18). Television current affairs programmes have from their inception been a flagship genre in the schedules of public service broadcasters. As a television form they were to background, contextualise and examine in depth issues which may have appeared in the news. They clearly met the public broadcasters' brief to 'inform and educate' and contribute to the notional 'public sphere'. Over the past two decades policies of deregulation and the impact of new media technologies have arguably diminished the role of public broadcasting and profoundly affected the resources available for current or public affairs television with subsequent impacts on its forms and importance. This paper looks at the output of one public broadcaster, Television New Zealand (TVNZ), and examines its current affairs programming through this period of change Communications, Civics, Industry – ANZCA2007 Conference Proceedings Death of a Genre? 2 Introduction From their inception current affairs programmes have played an important part in the schedules of public broadcasters offering a platform for citizens to debate and assess issues of importance. They are part of the public sphere in which the audience is considered to be made up of thoughtful, participating citizens who use the media to help them learn about the world and debate their responses and reach informed decisions about what courses of action to adopt (Dahlgren & Sparks, 1991). -

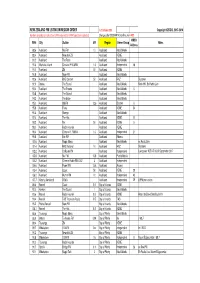

NZL FM List in Regional Order Oct19.Xlsx

NEW ZEALAND FM LISTING IN REGION ORDER to 1 October 2019 Copyright NZRDXL 2017-2019 Full-time broadcasters plus their LPFM relays (other LPFM operators excluded) Changes after 2020 WRTH Deadline are in RED WRTH MHz City Station kW Region Owner/Group Notes Address 88.6 Auckland Mai FM 10 Auckland MediaWorks 89.4 Auckland Newstalk ZB Auckland NZME 90.2 Auckland The Rock Auckland MediaWorks 90.6 Waiheke Island Chinese R 90.6FM 1.6 Auckland Independent 18 91.0 Auckland ZM 50 Auckland NZME 91.8 Auckland More FM Auckland MediaWorks 92.6 Auckland RNZ Concert 50 Auckland RNZ Skytower 92.9 Orewa The Sound Auckland MediaWorks Moirs Hill. Ex Radio Live 93.4 Auckland The Breeze Auckland MediaWorks 5 93.8 Auckland The Sound Auckland MediaWorks 94.2 Auckland The Edge Auckland MediaWorks 95.0 Auckland 95bFM 12.6 Auckland Student 6 95.8 Auckland Flava Auckland NZME 34 96.6 Auckland George Auckland MediaWorks 97.4 Auckland The Hits Auckland NZME 10 98.2 Auckland Mix 50 Auckland NZME 5 99.0 Auckland Radio Hauraki Auckland NZME 99.4 Auckland Chinese R. FM99.4 1.6 Auckland Independent 21 99.8 Auckland Life FM Auckland Rhema 100.6 Auckland Magic Music Auckland MediaWorks ex Radio Live 101.4 Auckland RNZ National 10 Auckland RNZ Skytower 102.2 Auckland OnRoute FM Auckland Independent Low power NZTA Trial till September 2017 103.8 Auckland Niu FM 15.8 Auckland Pacific Media 104.2 Auckland Chinese Radio FM104.2 3 Auckland Independent 104.6 Auckland Planet FM 15.8 Auckland Access 105.4 Auckland Coast 50 Auckland NZME 29 106.2 Auckland Humm FM 10 Auckland Independent -

CRL Mediaworks

IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 AND Notices of Requirement by AUCKLAND TRANSPORT pursuant to section 168 of the Act to the Auckland Council relating to the proposed City Rail Link in Auckland ______________________________________________________________ EVIDENCE OF PETER CROSSAN ON BEHALF OF MEDIAWORKS NZ LIMITED (IN RECEIVERSHIP) AND TVWORKS LIMITED (IN RECEIVERSHIP) Dated: 26 July 2013 ______________________________________________________________ CEK-100742-1-31-V4 INTRODUCTION My full name is PETER GARY CROSSAN and I am the Chief Financial Officer at MediaWorks NZ Limited (in receivership). 1. I joined MediaWorks NZ Limited in December 1999 following a 15 year career in various manufacturing industries. After 13 years at MediaWorks NZ Limited, I believe I have insight and in-depth knowledge of the wider television industry. 2. I am a qualified Chartered Accountant and have a B Comm from Auckland University. 3. I am authorised to give evidence on behalf of MediaWorks NZ Limited and TVWorks Limited (in receivership) (collectively referred to in this statement as “MediaWorks”) in relation to the City Rail Link Project (“the Project”). TVWorks Limited is a wholly owned subsidiary of MediaWorks NZ Limited. MEDIAWORKS 4. MediaWorks is an independent commercial (non-state funded) broadcaster. It provides TV, Radio and Interactive services: a. MediaWorks TV encompasses the national stations TV3 and FOUR. b. MediaWorks Radio operates out of 23 markets and consists of the nationwide brands MORE FM, RadioLIVE, The Sound, The Edge, The Breeze, The Rock, Mai FM, George FM, LiveSPORT and Kiwi FM, as well as Times FM in Orewa, Radio Dunedin and Coromandel FM. c. -

Epochality, Temporality and Media-Communication Ownership in Aotearoa-New Zealand

MEDIANZ VOL 17 NO 1 • 2017 https://DOI.org/10.11157/medianz-vol17iss1id179 - ARTICLE - Epochality, Temporality and Media-Communication Ownership in Aotearoa-New Zealand Wayne Hope Abstract Amidst academic policy debates over the proposed Fairfax-NZME and Sky-Vodafone mergers, the historical patterns of media-communication ownership received little mention. The purpose of this article is to explain, firstly, how the very possibility of such mergers eventuated and, secondly, why associated epochal reconfigurations in the political economy of New Zealand capitalism eluded public depiction. Initially I examine the repercussions which arose from: the restructuring of Radio New Zealand and Television New Zealand into State-Owned Enterprises (1987); the arrival of TV3 (1989); the formation of pay-subscription Sky Television (1990); and the abolition of all legal restrictions on foreign media ownership (1991). Together these events signalled the hollowing out of New Zealand’s media-communication system and the unfolding ownership patterns of conglomeration, transnationalisation and financialisation. Behind this critical narrative, I explore how the simultaneous restructuring of the national political economy, mediated public life and the vocabulary of economics obfuscated the epochal shift that was taking place. An ongoing lack of public awareness about this shift has debilitated normatively-grounded critiques of the contemporary media landscape and the ownership patterns which came to prevail. Prologue: From National to Transnational Media Ownership in Epochal Context In simple terms, an epoch is an identifiable period of history marked by special events. Natural-scientific conceptions of evolutionary epochal change can be distinguished from the idea that epochs are brought into historical being by manifestations of collective self- consciousness. -

Reaching the Community Through Community Radio

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UC Research Repository REACHING THE COMMUNITY THROUGH COMMUNITY RADIO Readjusting to the New Realities A Case Study Investigating the Changing Nature of Community Access and Participation in Three Community Radio Stations in Three Countries New Zealand, Nepal and Sri Lanka __________________________________________________________________________ A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Ahmed Zaki Nafiz University of Canterbury 2012 _____________________________________________________________________________ Dedicated to my beloved parents: Abdulla Nafiz and Rasheeda Mohammed Didi i ABSTRACT Community radio is often described as a medium that celebrates the small community life and where local community members plan, produce and present their own programmes. However, many believe that the radio management policies are now increasingly sidelining this aspect of the radio. This is ironic given the fact that the radio stations are supposed to be community platforms where members converge to celebrate their community life and discuss issues of mutual interest. In this case study, I have studied three community radio stations- RS in Nepal, KCR in Sri Lanka and SCR in New Zealand- investigating how the radio management policies are positively or negatively, affecting community access and participation. The study shows that in their effort to stay economically sustainable, the three stations are gradually evolving as a ‘hybrid’; something that sits in-between community and commercial radio. Consequently, programmes that are produced by the local community are often replaced by programmes that are produced by full-time paid staff; and they are more entertaining in nature and accommodate more advertisements.