The Display of Self and Others at Chicago's 1893 World Fair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World's Columbian Exposition: Idea, Experience, Aftermath

The World's Columbian Exposition: Idea, Experience, Aftermath Julie Kirsten Rose Morgan Hill, California B.A., San Jose State University, 1993 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia August 1996 L IV\CLslerI s E~A-3 \ ~ \qa,(c, . R_to{ r~ 1 COLOPHON AND DEDICATION This thesis was conceived and produced as a hypertextual project; this print version exists solely to complete the request and requirements of department of Graduate Arts and Sciences. To experience this work as it was intended, please point your World Wide Web browser to: http:/ /xroads.virginia.edu/ ~MA96/WCE/title.html Many thanks to John Bunch for his time and patience while I created this hypertextual thesis, and to my advisor Alan Howard for his great suggestions, support, and faith.,.I've truly enjoyed this year-long adventure! I'd like to dedicate this thesis, and my work throughout my Master's Program in English/ American Studies at the University of Virginia to my husband, Craig. Without his love, support, encouragement, and partnership, this thesis and degree could not have been possible. 1 INTRODUCTION The World's Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, was the last and the greatest of the nineteenth century's World's Fairs. Nominally a celebration of Columbus' voyages 400 years prior, the Exposition was in actuality a reflection and celebration of American culture and society--for fun, edification, and profit--and a blueprint for life in modem and postmodern America. -

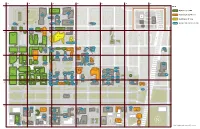

KEY KEY Last Updated: June 15, 2020

Friend Family Health Center Ronald McDonald House A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST KEY 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Building is OPEN Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S Building is COMPLETE AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Building is IN-USE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - DATE EXPECTED READY DATE AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S KIMBARK AVE S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer CollegiumJUNE 19 Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - -

Insider's Guide

ALL THINGS visit.uchicago.edu VALOIS RESTAURANT 1518 E. 53rd St. insider’s valoisrestaurant.com President Obama’s favorite breakfast spot! They serve classic soul food for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Get guide this: they serve breakfast all day! If you forget cash for this cash-only establishment, worry not, there is an ATM Have you ever wondered what Hyde Park does inside. for fun? Sure you have! For a true taste of Hyde Park and its surrounding neighborhoods, check ORIENTAL INSTITUTE LIBRARY 1155 E. 58th St. out these not-to-be-missed South Side gems. Although Harper Memorial Library tends to attract more PROMONTORY POINT tourists and studiers alike, the Oriental Institute is home to 5491 S. South Shore Dr. a smaller, but just as beautiful reading room. Once inside, chicagoparkdistrict.com/parks/Burnham-Park/ head up the stone steps to the second floor and take a If you are looking for a great view of the lake and the right. Open 10am-5pm. Chicago skyline, or maybe just a calming place to sit and read, Promontory Point is the site to visit. A great UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PUB destination for picnics, sunsets, and people-watching, 1212 E. 59th St. “The Point” is located on Chicago’s Lake Front Trail, which Ida Noyes Hall, lower level stretches south to 95th Street and all the way north to leadership.uchicago.edu/orcsas-pub Navy Pier. Long gone are the days of indoor smoking and 50-cent cans of PBR, but “The Pub,” as it’s known on campus, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CAMPUS BOTANY maintains its status as a reliably fun place for students and botanicgarden.uchicago.edu faculty alike. -

City of Chicago Analysis of Its Proposal Related to Jackson Park, Cook County, Illinois Under the Urban Parks and Recreation Recovery Act Program

City of Chicago Analysis of its Proposal Related to Jackson Park, Cook County, Illinois under the Urban Parks and Recreation Recovery Act Program November 2019 [as revised May 2020] Prepared by the City of Chicago Federal Actions In and Adjacent to Jackson Park Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 UPARR .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Statutory and Regulatory Background ....................................................................... 2 1.2.2 UPARR Grants and Program Requirements at Jackson Park ...................................... 2 1.3 Municipal Consideration of and Approval of the Proposal to Locate the OPC in Jackson Park ............................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Jackson Park and Midway Plaisance: Existing Recreation Uses and Opportunities ..................................................................................... 6 2.1 Jackson Park: Overview .......................................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Existing Recreation Facilities....................................................................................... 8 2.1.2 Existing Recreation -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

YOUNG LEADERS PROGRAM October 16-19, 2019 Chicago, Illinois TABLE of CONTENTS

YOUNG LEADERS PROGRAM October 16-19, 2019 Chicago, Illinois TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE FRENCH-AMERICAN FOUNDATION 2 AND THE YOUNG LEADERS PROGRAM OUR SUPPORTERS & SPONSORS 3 PROGRAM AGENDA 6 BIOGRAPHIES OF YOUNG LEADERS 11 BIOGRAPHIES OF SPEAKERS 32 BIOGRAPHIES OF FOUNDATION LEADERSHIP AND STAFF 39 THINGS TO SEE, DO, & EAT IN CHICAGO 46 FRENCH-AMERICAN FOUNDATION 1 SUPPORTERS & SPONSORS THE FRENCH-AMERICAN FOUNDATION—UNITED STATES WOULD LIKE TO THANK THE FOLLOWING SUPPORTERS: ABOUT THE FRENCH-AMERICAN FOUNDATION We are grateful for the leading partnership of the Since their founding in 1976, the French-American Foundation—United States AMERICAN EXPRESS FOUNDATION and the French-American Foundation—France have been committed to enriching in support of the 2019 Young Leaders Program. We would like to thank the a transatlantic relationship that is essential in today’s world. The Foundations Board of Directors for their generosity and support. Special thanks also go to bring together French and American leaders, policymakers and a wide range of the individual and corporate contributors to our 2019 Gala. professionals to exchange views on common problems and to create productive, lasting links between people which have a far-reaching effect in both countries. WE WOULD ALSO LIKE TO THANK THE FOLLOWING IN-KIND To accomplish these objectives, the Foundations arrange a wide variety of CONTRIBUTORS TO THE YOUNG LEADERS PROGRAM: programs, including conferences, lectures, prizes, and its principal Young Leaders Theory and Siddhartha Shukla ‘16 program, -

The Cairo Street at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

Nabila Oulebsir et Mercedes Volait (dir.) L’Orientalisme architectural entre imaginaires et savoirs Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 István Ormos DOI: 10.4000/books.inha.4915 Publisher: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art Place of publication: Paris Year of publication: 2009 Published on OpenEdition Books: 5 December 2017 Serie: InVisu Electronic ISBN: 9782917902820 http://books.openedition.org Electronic reference ORMOS, István. The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 In: L’Orientalisme architectural entre imaginaires et savoirs [online]. Paris: Publications de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, 2009 (generated 18 décembre 2020). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/ inha/4915>. ISBN: 9782917902820. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.inha.4915. This text was automatically generated on 18 December 2020. The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 1 The Cairo Street at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 István Ormos AUTHOR'S NOTE This paper is part of a bigger project supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA T048863). World’s fairs 1 World’s fairs made their appearance in the middle of the 19th century as the result of a development based on a tradition of medieval church fairs, displays of industrial and craft produce, and exhibitions of arts and peoples that had been popular in Britain and France. Some of these early fairs were aimed primarily at the promotion of crafts and industry. Others wanted to edify and entertain: replicas of city quarters or buildings characteristic of a city were erected thereby creating a new branch of the building industry which became known as coulisse-architecture. -

Preservation Chicago

Preservation Chicago Citizens advocating for the preservation of Chicago’s historic architecture Preservation Chicago Citizens advocating for theJune preservation 9, 2011 of Chicago’s historic architecture Andrew Mooney Commissioner, Department of Housing and Economic Development City Hall – 121 N. LaSalle, 10th Floor JanuaryChicago, 04, 2018IL 60602 Brad Suster June 9, 2011 PresidentPresident Re: Support for St. Boniface church adaptive reuse plan Ward Miller* Ms. EleanorAndrew Gorski, Mooney Deputy Commissioner, Department of Planning and Development,Dear Commissioner Historic Mooney, Preservation Division JacobVice KaplanPresident Commissioner, Department of Housing and Economic Development Jack Spicer* Vice President Mr.I Johnam Citywriting Sadler, Hall in supportChicago– 121 ofN. Departmentthe LaSalle, proposed 10th adaptiveof Transportation Floor reuse plan for the former St. Boniface Church, Secretary locatedChicago, at 1328 W.IL Chestnut60602 and 921 N. Noble, presented to us by IMP Development earlier this ! Debbie Dodge* Ms.week. Abby TheMonroe, latest proposalCoordinating incorporates Planner the, adaptiveDepartment reuse ofof anPlanning existing andhistoric structure coupled Development DebbieTreasurer Dodge with new construction. PresidentGreg Brewer* Re: Support for St. Boniface church adaptive reuse plan SecretaryWard Miller* City of Chicago Board of Directors Efforts to preserve and repurpose this important neighborhood structure date to 1998 and Preservation ! Beth Baxter 121 N. LaSalleDear Commissioner Street Mooney, -

Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago's Parks

Daniel H. Burnham and Chicago’s Parks by Julia S. Bachrach, Chicago Park District Historian In 1909, Daniel H. Burnham (1846 – 1912) and Edward Bennett published the Plan of Chicago, a seminal work that had a major impact, not only on the city of Chicago’s future development, but also to the burgeoning field of urban planning. Today, govern- ment agencies, institutions, universities, non-profit organizations and private firms throughout the region are coming together 100 years later under the auspices of the Burnham Plan Centennial to educate and inspire people throughout the region. Chicago will look to build upon the successes of the Plan and act boldly to shape the future of Chicago and the surrounding areas. Begin- ning in the late 1870s, Burnham began making important contri- butions to Chicago’s parks, and much of his park work served as the genesis of the Plan of Chicago. The following essay provides Daniel Hudson Burnham from a painting a detailed overview of this fascinating topic. by Zorn , 1899, (CM). Early Years Born in Henderson, New York in 1846, Daniel Hudson Burnham moved to Chi- cago with his parents and six siblings in the 1850s. His father, Edwin Burnham, found success in the wholesale drug busi- ness and was appointed presidet of the Chicago Mercantile Association in 1865. After Burnham attended public schools in Chicago, his parents sent him to a college preparatory school in New England. He failed to be accepted by either Harvard or Yale universities, however; and returned Plan for Lake Shore from Chicago Ave. on the north to Jackson Park on the South , 1909, (POC). -

A Week at the Fair; Exhibits and Wonders of the World's Columbian

; V "S. T 67>0 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ""'""'"^ T 500.A2R18" '""''''^ "^"fliiiiWi'lLi£S;;S,A,.week..at the fair 3 1924 021 896 307 'RAND, McNALLY & GO'S A WEEK AT THE FAIR ILLUSTRATING THE EXHIBITS AND WONDERS World's Columbian Exposition WITH SPECIAL DESCRIPTIVE ARTICLES Mrs. Potter Palmer, The C6untess of Aberdeen, Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer, Mr. D. H. Burnh^m (Director of Works), Hon. W. E. Curtis, Messrs. Adler & Sullivan, S. S. Beman, W. W. Boyington, Henry Ives Cobb, W, J. Edbrooke, Frank W. Grogan, Miss Sophia G. Havden, Jarvis Hunt, W. L. B. Jenney, Henry Van Brunt, Francis Whitehouse, and other Architects OF State and Foreign Buildings MAPS, PLANS, AND ILLUSTRATIONS CHICAGO Rand, McNally & Company, Publishers 1893 T . sod- EXPLANATION OF REFERENCE MARKS. In the following pages all the buildings and noticeable features of the grounds are indexed in the following manner: The letters and figures following the names of buildings in heavy black type (like this) are placed there to ascertain their exact location on the map which appears in this guide. Take for example Administration Building (N i8): 18 N- -N 18 On each side of the map are the letters of the alphabet reading downward; and along the margin, top and bottom, are figures reading and increasing from i, on the left, to 27, on the right; N 18, therefore, implies that the Administration Building will be found at that point on the map where lines, if drawn from N to N east and west and from 18 to 18 north and south, would cross each other at right angles. -

Self-Guided Tours

ALL THINGS visit.uchicago.edu IF YOU HAVE 4 HOURS self-guided BOTANY POND 57th St. (west of Hutchinson Court) Located in the middle of campus, Botany Pond is the university’s tours biodiversity hotspot, hosting a remarkable variety of animals including ducks, four species of turtles, and a dozen species of dragonflies. For over a century, the pond has served as a tranquil IF YOU HAVE 1 HOUR outdoor study space, relaxation destination, and nexus of intel- lectual life on campus. Plus, rumor has it, if a couple kisses on the MAIN QUAD bridge over Botany Pond, they will get married. 57th St. – 59th St. Between University Ave. and Ellis Ave. architecture.uchicago.edu ROCKEFELLER MEMORIAL CHAPEL 5850 S. Woodlawn Ave. (at E. 59th St.) The centerpiece of the University of Chicago campus rockefeller.uchicago.edu/events is without question its main quadrangle. Designed in 1891 by famed Chicago architect Henry Ives Cobb, Rockefeller Memorial Chapel is a hub for ceremonies, the Neo-Gothic style of the Quad lends itself to theater, orchestral performances, chorus groups, classrooms, laboratories, and libraries alike. At vari- concerts, and even circus acts. While you’re there, ous points in the year, the Main Quad is the site of make sure to walk up the 271 steps to the top for 360 everything from quiet study and relaxation to the degree views of Chicago, Lake Michigan, northern bustling Spring Convocation ceremony. Indiana and the port, the Michigan shoreline, and of course, the University itself. Visit the Rockefeller Memorial Chapel website for information on daily Car- HARPER MEMORIAL LIBRARY READING ROOM illon tours, nondenominational religious services, and 1116 E. -

Chicago No 16

CLASSICIST chicago No 16 CLASSICIST NO 16 chicago Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 20 West 44th Street, Suite 310, New York, NY 10036 4 Telephone: (212) 730-9646 Facsimile: (212) 730-9649 Foreword www.classicist.org THOMAS H. BEEBY 6 Russell Windham, Chairman Letter from the Editors Peter Lyden, President STUART COHEN AND JULIE HACKER Classicist Committee of the ICAA Board of Directors: Anne Kriken Mann and Gary Brewer, Co-Chairs; ESSAYS Michael Mesko, David Rau, David Rinehart, William Rutledge, Suzanne Santry 8 Charles Atwood, Daniel Burnham, and the Chicago World’s Fair Guest Editors: Stuart Cohen and Julie Hacker ANN LORENZ VAN ZANTEN Managing Editor: Stephanie Salomon 16 Design: Suzanne Ketchoyian The “Beaux-Arts Boys” of Chicago: An Architectural Genealogy, 1890–1930 J E A N N E SY LV EST ER ©2019 Institute of Classical Architecture & Art 26 All rights reserved. Teaching Classicism in Chicago, 1890–1930 ISBN: 978-1-7330309-0-8 ROLF ACHILLES ISSN: 1077-2922 34 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Frank Lloyd Wright and Beaux-Arts Design The ICAA, the Classicist Committee, and the Guest Editors would like to thank James Caulfield for his extraordinary and exceedingly DAVID VAN ZANTEN generous contribution to Classicist No. 16, including photography for the front and back covers and numerous photographs located throughout 43 this issue. We are grateful to all the essay writers, and thank in particular David Van Zanten. Mr. Van Zanten both contributed his own essay Frank Lloyd Wright and the Classical Plan and made available a manuscript on Charles Atwood on which his late wife was working at the time of her death, allowing it to be excerpted STUART COHEN and edited for this issue of the Classicist.