RESOURCES in Preparation for Dying, Death and Burial (Inside Front Cover) RESOURCES in Preparation for Dying, Death and Burial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Beyond Death by Swami Abhedananda

Life Beyond Death Lectures of Swami Abhedananda A Great Yogi and Direct Disciple of Sri Ramakrishna Life Beyond Death – lovingly restored by The Spiritual Bee An e-book presentation by For more FREE books visit the website: www.spiritualbee.com Dear Reader, This book has been reproduced here from the Complete Works of Swami Abhedananda, Volume 4. The book is now in the public domain in India and the United States, because its original copyright has expired. “Life beyond Death” is a collection of lectures delivered by Swami Abhedananda in the United States. Unlike most books on the subject which mainly record encounters with ghosts and other kinds of paranormal activities, this book looks at the mystery from a soundly rational and scientific perspective. The lectures initially focus on providing rational arguments against the material theory of consciousness, which states that consciousness originates as a result of brain activity and therefore once death happens, consciousness also ends and so there is no such thing as a life beyond death. Later in the book, Swami Abhedananda also rallies against many dogmatic ideas present in Christian theology regarding the fate of the soul after death: such as the philosophies of eternal damnation to hell, resurrection of the physical body after death and the belief that the soul has a birth, but no death. In doing so Swami Abhedananda who cherished the deepest love and respect for Christ, as is evident in many of his other writings such as, “Was Christ a Yogi” (from the book How to be a Yogi?), was striving to place before his American audience, higher and more rational Vedantic concepts surrounding life beyond the grave, which have been thoroughly researched by the yogi’s of India over thousands of years. -

Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549

“JUST AS THE PRIESTS HAVE THEIR WIVES”: PRIESTS AND CONCUBINES IN ENGLAND, 1375-1549 Janelle Werner A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Advisor: Professor Judith M. Bennett Reader: Professor Stanley Chojnacki Reader: Professor Barbara J. Harris Reader: Cynthia B. Herrup Reader: Brett Whalen © 2009 Janelle Werner ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JANELLE WERNER: “Just As the Priests Have Their Wives”: Priests and Concubines in England, 1375-1549 (Under the direction of Judith M. Bennett) This project – the first in-depth analysis of clerical concubinage in medieval England – examines cultural perceptions of clerical sexual misbehavior as well as the lived experiences of priests, concubines, and their children. Although much has been written on the imposition of priestly celibacy during the Gregorian Reform and on its rejection during the Reformation, the history of clerical concubinage between these two watersheds has remained largely unstudied. My analysis is based primarily on archival records from Hereford, a diocese in the West Midlands that incorporated both English- and Welsh-speaking parishes and combines the quantitative analysis of documentary evidence with a close reading of pastoral and popular literature. Drawing on an episcopal visitation from 1397, the act books of the consistory court, and bishops’ registers, I argue that clerical concubinage occurred as frequently in England as elsewhere in late medieval Europe and that priests and their concubines were, to some extent, socially and culturally accepted in late medieval England. -

35-Burial of the Dead

REGARDING CHRISTIAN DEATH AND BURIAL The burial of a Christian is an occasion of both sorrow and joy—our sorrow in the face of death, and our joy in Jesus’ promise of the resurrection of the body and the life everlasting. As the burial liturgy proclaims, “life is changed, not ended; and when our mortal body lies in death, there is prepared for us a dwelling place eternal in the heavens.” The Christian burial liturgy looks forward to eternal life rather than backward to past events. It does not primarily focus on the achievements or failures of the deceased; rather, it calls us to proclaim the Good News of Jesus and his triumph over death, even as we celebrate the life and witness of the deceased. The readings should always be drawn from the Bible, and the prayers and music from the Christian tradition. A wake preceding the service and a reception following the service are appropriate places for personal remembrances. Where possible, the burial liturgy is conducted in a church, and it is often celebrated within the context of the Eucharist. The Book of Common Prayer has always admonished Christians to be mindful of their mortality. It is therefore the duty of all Christians, as faithful stewards, to draw up a Last Will and Testament, making provision for the well-being of their families and not neglecting to leave bequests for the mission of the Church. In addition, it is important while in health to provide direction for one’s own funeral arrangements, place of burial, and the Scripture readings and hymns of the burial liturgy, and to make them known to the Priest. -

A Catholic Funeral Planning Guide the Church of Christ Our Light

1 A CATHOLIC FUNERAL PLANNING GUIDE THE CHURCH OF CHRIST OUR LIGHT PRINCETON / ZIMMERMAN 12/28/15 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................3 FUNERAL STIPEND GUIDELINES .....................................................................4 PARISH PRAYERS / VISITATION.......................................................................5 FUNERAL MASS / SERVICE ...............................................................................6 LUNCHEON………………………………………………………………………6 CREMATION ..........................................................................................................7 SCRIPTURE READINGS ....................................................... 8-9 & Yellow Inserts MUSIC…………………………………………………………………………9-10 PRAYERS OF THE FAITHFUL (PETITIONS) ..................................................11 GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................12 PLANNING THE FUNERAL LITURGY ...................................................... 13-14 LECTORS .............................................................................................................15 EULOGY ...............................................................................................................16 2 3 INTRODUCTION Dealing with death and grief over the loss of a loved one is very painful. During such an emotional time, it is hard to make decisions, and yet, there are necessary arrangements that must be made. -

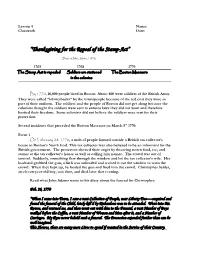

Lesson 4 Name: Classwork Date

Lesson 4 Name: Classwork Date: “Thanksgiving for the Repeal of the Stamp-Act” (Diary of John Adams, 1:316) 1765 1768 1770 The Stamp Act is repealed Soldiers are stationed The Boston Massacre in the colonies By 1770, 16,000 people lived in Boston. About 600 were soldiers of the British Army. They were called “lobsterbacks” by the townspeople because of the red coat they wore as part of their uniform. The soldiers and the people of Boston did not get along because the colonists thought the soldiers were sent to enforce laws they did not want and therefore limited their freedom. Some colonists did not believe the soldiers were sent for their protection. Several incidents that preceded the Boston Massacre on March 5th 1770: Event 1 On February 28, 1770, a mob of people formed outside a British tax collector’s house in Boston’s North End. This tax collector was also believed to be an informant for the British government. The protestors showed their anger by throwing rotten food, ice, and stones at the tax collector’s house as well as calling him names. The crowd was out of control. Suddenly, something flew through the window and hit the tax collector’s wife. Her husband grabbed the gun, which was unloaded and waived it out the window to warn the crowd. When they kept up, he loaded the gun and fired into the crowd. Christopher Seider, an eleven-year-old boy, was shot, and died later that evening. Read what John Adams wrote in his diary about the funeral for Christopher: Feb. -

A Guide to Funeral Planning

St. John the Beloved Catholic Church McLean, Virginia INTRODUCTION On behalf of all your fellow parishioners, the priests and staff of Saint John the Beloved Church extend to your family our prayerful sympathy in this time of loss and grief. There are many people praying for you and with you. The hundreds of members of the St. John Prayer Chain are lifting you up in prayer. At Sunday Mass we all will be praying for your loved one and your family. On the first Saturday after All Souls Day we will be together and pray for all those who passed away in the previous year. You are not alone. When we gather for the Mass of Christian Burial at St. John the Beloved we also transcend time and join the faithful sinners and saints who have offered up the same prayers for their loved ones over the past twenty centuries. In the ancient tradition of the classic Requiem Mass, we can feel our prayers carried aloft by the angels with the Sacred Scriptures and monastic chants that have been used at the burial rites of Christians for far more than one thousand years. In the Sacred Liturgy we experience the consolation of praying with each other, with the whole Church, with all the saints and with Jesus Christ Himself and of having them pray for us. This tangible connection with the Communion of Saints, those who pray for us in heaven and even those who still need us to pray for them, can be a comfort and consolation for us as we mourn the loss of a loved one. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Second Death! Eternal=Immortality

Eternal=Second Death! Eternal=Immortality. Heb. 9:27 And as it is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment: Ps. 89:48 What man is he that liveth, and shall not see death? shall he deliver his soul from the hand of the grave? Selah. Ecc. 3:19 For that which befalleth the sons of men befalleth beasts; even one thing befalleth them: as the one dieth, so dieth the other; yea, they have all one breath; so that a man hath no preeminence above a beast: for all is vanity. 3:20 All go unto one place; all are of the dust, and all turn to dust again. 1 Kings 2:2 I go the way of all the earth: be thou strong therefore, and show thyself a man; Ps. 102:25 Of old hast thou laid the foundation of the earth: and the heavens are the work of thy hands. 102:26 They shall perish, but thou shalt endure: yea, all of them shall wax old like a garment; as a vesture shalt thou change them, and they shall be changed: Rev. 20:6 Blessed and holy is he that hath part in the first resurrection: on such the second death hath no power, but they shall be priests of God and of Christ, and shall reign with him a thousand years. It will be admitted by all that Adam was placed on probation, and that the penalty of death, absolute and irrevocable, was affixed to the violation of the command not to eat of the forbidden tree. -

The Importance of Koliva

24 THURSDAY 16 APRIL 2009 NEWS IN ENGLISH Ï Êüóìïò Pilgrimage tourism initiative by Russia, Greece Promotion of pilgrimage tourism between Markopoulos underlined the nomic crisis. Russia and Greece through the establish- Russian Patriarch's positive response In statements he made after the meeting at the ment of a joint coordinating committee was to the initiative and stated that the Patriarchal residence, Markopoulos stated that the decided here during a meeting between Greek side's intention is to make Patriarch referred to his "warm relation" with Patriarch Kyrill of Moscow and All Russia Russia an attractive tourist destination Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I, adding that "all and visiting Greek Tourism Development for the Greeks adding, at the same indications show that we are entering a new phase in Minister Costas Markopoulos. time, that more Russians are expected the history of the two Churches and Patriarchates," Markopoulos, the first Greek government to visit Greece this year. characterizing it as a positive development. minister to be received by the new Patriarch Welcoming Markopoulos, the Markopoulos had meetings with the local govern- of Russia, stated that the committee will be Russian Patriarch stated that the num- ment in the Russian capital to discuss the promotion of comprised of three Russian Church members, Church ber of Russian tourists visiting Greece is smaller than Greece's tourist campaign in the greater Moscow of Greece representatives as well as a Greek tourism desired and pointed out that Greece offers countless region and attended the first screening of the film "El ministry official. He also stated that the initiative reaf- attractive destinations expressing the wish that bilater- Greco" in Russian cinemas. -

Weekly Bulletin

WEEKLY BULLETIN SAINT ELIA THE PROPHET ORTHODOX CHURCH A Parish of the Orthodox Church in America 64 West Wilbeth Road, Akron, Ohio 44301 Church Hall: 330-724-7129 Office: 330-724-7009 www.saintelia.com www.facebook.com/sainteliaakron His Eminence Alexander, Archbishop of Toledo, Bulgarian Diocese, OCA Very Rev. Mitred Archpriest Father Don Anthony Freude, Parish Rector Rev. Protodeacon James M. Gresh, Attached March 10, 2019 Vol. 36 No. 10 SCHEDULE OF DIVINE SERVICES 4th Pre-Lenten Sunday CHEESEFARE SUNDAY-Tone 8 - FORGIVENESS SUNDAY. The Expulsion of Adam from Paradise Saturday, March 9 - 5:00 pm Great Vespers and Confessions Sunday, March 10 9:45 am Hours: Reader Aaron Gray 10:00 am Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom Vespers and Mutual Forgiveness Service Epistle Reader: Reader Aaron Gray EPISTLE: Romans 13:11-14:4 GOSPEL: Matt. 6:14-21 BEGINNING OF GREAT LENT Let us set out with joy upon the season of the Fast…and with prayers and tears let us seek our Lord and Savior. FIRST WEEk of GREAT LENT Monday, March 11 – 6:00 pm- Great Canon of Repentance of St. Andrew of Crete – 1st Section Tuesday, March 12 – 6:00 pm Great Canon of Repentance of St. Andrew of Crete –2nd Section REMEMBER THOSE SERVING IN THE ARMED FORCES Subdeacon Anthony Freude, son of Fr, Don and Popadia Donna Freude Egor Cravcenco, son of Serghei and Ludmila Cravcenco REMEMBER OUR SICK AND SHUT-INS Mickey Stokich Leonora Evancho Larissa Freude Anastasia Haymon Joseph Boyle, (Kathy Gray’s brother) Phyllis George, (Rose Marie Vronick’s sister) Connie Pysell Lisa Nastoff Elaine Pedder Sandra Dodovich, (mother of Tony Dodovich) Angelo and Florence Lambo Carl Palcheff Gary Turner (father of Joseph Turner) Infant Child Aria COFFEE HOUR: Church School Fundraiser PROSPHORA: Veronica Bilas OUR STEWARDSHIP: March 3, 2019 Sunday Offering: $706.78 PARKING LOT Candles: 25.50 To Date: $17,450.00 Improvement Fund: 70.00 Bookstore: 8.00 FURNACE/AC TOTAL $810.28 To Date: $8,150.00 QUARTER AUCTION: $1,700.00 AMAZON SMILE – Support St. -

Baptized Christians Who Have Died and Are Now with God in Glory Are Considered Saints

Father’s Corner Dear Loving parishioners, Love and Peace of Christ! The feast and its objectives: All baptized Christians who have died and are now with God in glory are considered saints. All Saints Day is intended to honor the memory of countless unknown and uncanonized saints who have no feast days. Today we thank God for giving ordinary men and women a share in His holiness and Heavenly glory as a reward for their Faith. This feast is observed to teach us to honor the saints, both by imitating their lives and by seeking their intercession for us before Christ, the only mediator between God and man (I Tm 2:5). The Church reminds us today that God’s call for holiness is universal, that all of us are called to live in His love and to make His love real in the lives of those around us. Holiness is related to the word wholesomeness. We grow in holiness when we live wholesome lives of integrity, truth, justice, charity, mercy, and compassion, sharing our blessings with others. We can take the shortcuts practiced by the three T(h)eresas: i) St. Teresa of Avila: Recharge your spiritual batteries every day by prayer, namely, listening to God and talking to Him ii) St. Therese of Lisieux: Convert every action into prayer by offering it to God for His glory and for the salvation of souls and by doing God’s will to the best of your ability. iii) St. Teresa of Calcutta (Mother Teresa): Do ordinary things with great love. -

Forgetting Oblivion: the Demise of the Legislative Pardon

Cornell Law Library Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Working Papers Faculty Scholarship 3-31-2011 Forgetting Oblivion: The eD mise of the Legislative Pardon Bernadette A. Meyler Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clsops_papers Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Legal History, Theory and Process Commons Recommended Citation Meyler, Bernadette A., "Forgetting Oblivion: The eD mise of the Legislative Pardon" (2011). Cornell Law Faculty Working Papers. Paper 83. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clsops_papers/83 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. * BERNADETTE MEYLER FORGETTING OBLIVION : THE DEMISE OF THE LEGISLATIVE PARDON TABLE OF CONTENTS : I INTRODUCTION ...........................................................1 II FROM KLEIN TO KNOTE ...............................................6 III OBLIVION ENTERS ENGLAND ......................................13 IV COLONIAL AND STATE OBLIVIONS ..............................27 V PRAGMATICS OF PARDONING ......................................45 VI CONCLUSION ...............................................................49 I INTRODUCTION Despite several bouts of attempted reinterpretation,