The Advocate, Vol. 12, No. 4, July-August 1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Juliana Geran Pilon Education

JULIANA GERAN PILON [email protected] Dr. Juliana Geran Pilon is Research Professor of Politics and Culture and Earhart Fellow at the Institute of World Politics. For the previous two years, she taught in the Political Science Department at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. From January 1991 to October 2002, she was first Director of Programs, Vice President for Programs, and finally Senior Advisor for Civil Society at the International Foundation for Election Systems (IFES), after three years at the National Forum Foundation, a non-profit institution that focused on foreign policy issues - now part of Freedom House - where she was first Executive Director and then Vice President. At NFF, she assisted in creating a network of several hundred young political activists in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. For the past thirteen years she has also taught at Johns Hopkins University, the Institute of World Politics, George Washington University, and the Institute of World Politics. From 1981 to 1988, she was a Senior Policy Analyst at the Heritage Foundation, writing on the United Nations, Soviet active measures, terrorism, East-West trade, and other international issues. In 1991, she received an Earhart Foundation fellowship for her second book, The Bloody Flag: Post-Communist Nationalism in Eastern Europe -- Spotlight on Romania, published by Transaction, Rutgers University Press. Her autobiographical book Notes From the Other Side of Night was published by Regnery/Gateway, Inc. in 1979, and translated into Romanian in 1993, where it was published by Editura de Vest. A paperback edition appeared in the U.S. in May 1994, published by the University Press of America. -

UNEMPLOYMENT Eurostati3?ZI Statistical Telegram

.------------5m-1ll(#-7-. ·{_ UNEMPLOYMENT eurostatI3?ZI Statistical Telegram I I I 14 novembre 1980 MONTHLY STATISTICS OF REGISTERED UNEMPLOYED IN THE COMMUNITY - October 1980 - Unemployment in the Community continues to increase steadily. At the end of October 1980 it amounted to 7.4 million persons, or 6.7% of the civilian working population, compared with 7.1 million or 6.5% at the end of Septem ber. For the Community as a whole unemployment has thus risen by 3 percent in the course of the month. Particularly marked increases were recorded in Denmark and Luxembourg (10% or more) as well as in the F.R. of Germany (8%). Between October 1979 and October 1980 the total number of registered unemployed has risen by 1,281,000 persons or by more than 20% in one year. This increase even exceeded 50% in the United Kingdom and in Denmark and was of the order of 34% in the Netherlands and in Ireland. The smallest increases were noted in Luxem bourg (5.7%), in France (7.1%) and in Italy (8.4%). In those countries having the greatest increase in unemployment during the past year, the proportion of unemployed persons aged under 25 years has tended to increase. This proportion has been estimated at 41.4% at the end of October 1980 for the Community as a whole. The percentage of women in the total of unemployed has declined compared with October of last year in all Community countries with the exception of France where it has remained practically unchanged and of Italy and Luxembourg where it has increased. -

World Development Report, 1980

World Development Report, 1980 Part I Adjustment and growth in the 1980s Part II Poverty and human development Annex World Development Indicators The World Bank August 1950 World Development Report 1980 The World Bank Washington, D.C. August 1980 © 1980 by the international Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20433 U.S.A. All rights reserved. ISBN 0-19-502833-3 cloth ISBN 0-19-502834-1 paperback ISSN 0163-8058 The Library of Congress has cataloged this serial publication as follows: HC59 World development report. 1978- .7 [New York] Oxford University Press. .W659 v.27cm. annual. Published for the World Bank. 1. Underdeveloped areasPeriodicals.2. Economic development Periodicals.I. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. HC59.7.W659 330.9'172'4 78-67086 11 Foreword This third World Development Report reduce poverty, focusing on hu- the converse is true as welldirect is published at a time of difficulty man development, an important steps to reduce poverty do not and uncertainty for the world eco- complement to the approaches to obviate the need for growth. This nomyparticularly for the devel- poverty alleviation emphasized in Report emphasizes that the direct oping countries. They must adjust the two previous World Develop- attack on poverty, if it is ultimately to external payments imbalances, ment Reports. to be successful, must be com- higher energy prices and slower Human developmenteduca- bined with measures to ensure growth in world trade. That ad- tion and training, better health that the economies of the devel- justment will slow their growth and nutrition, and fertility reduc- oping countries continue to ex- for at least the next few years. -

Municipal Assistance Corporation for the City of New York (MAC) Archive MAC

Municipal Assistance Corporation for the City of New York (MAC) Archive MAC This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on June 14, 2019. Baruch College Archives, William and Anita Newman Library Digital Initiatives Librarian, Baruch College 1 Bernard Baruch Way New York, NY 10010 [email protected] URL: http://www.baruch.cuny.edu/library/alumni/archives.html Municipal Assistance Corporation for the City of New York (MAC) Archive MAC Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 7 Administrative History ................................................................................................................................... 7 Scope and Contents of the Collection ........................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement of the Collection ...................................................................................................................... 8 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 9 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................... 10 Series 2: Board of Directors Meeting Minutes ......................................................................................... 10 June 1975-August 1975 ......................................................................................................................... -

Maps Cited by Congress When Designating Wilderness

Maps Summary Table In 2003 long-time NPS Wilderness Coordinator Wes Henry prepared this table that was intended for inclusion in the updated Reference Manual 41 – Wilderness Management. Wes died soon thereafter. PEER has updated the table to reflect information through 2014. RM 41: Section F: DRAFT January 21, 2003 Maps Cited by Congress when Designating Wilderness. The table lists in: Column 2: maps cited by Congress when designating NPS wilderness (in chronological order by date of enactment); Column 3: date of an official legal description prepared after designation, and Column 4: whether a post-enactment official boundary map was prepared. NPS AREA – CONGRESSIONAL DATE OF DATE OF WILDERNESS MAP NUMBER OFFICIAL OFFICAL MAP DATE AND DATE, CITED LEGAL IN LAW DESCRIPTION Craters of the 131-91,000 December 1970 NPS cited Moon – Oct. 1970 March 1970 legislative map Petrified Forest - NP-PF-3320-O December 1970 NPS cited October 1970 November 1967 legislative map Lava Beds – NM-LB-3227H December 1972 NPS cited October 1972 August 1972 legislative map Lassen Volcanic – NP-LV-9013C June 1973 NPS cited October 1972 August 1972 legislative map Point Reyes – 612-90,000-B May 1978 February 1977 October 1976 September 1976 Bandelier – 315-20,014-B August 1978 August 1978 October 1976 May 1976 Black Canyon of 144-20,017 January 1977 January 1977 the Gunnison – May 1973 October 1976 Chiricahua - 145-20,007-A May 1978 January 1977 October 1976 September 1973 Great Sand Dunes 140-20,006-C December 1976; January 1980 October 1976 February 1976 Revised: -

Investigation of August 1980 Blowout and Fire, Lease OCS-G 2271 Vermilion Block 348, Gulf of Mexico Off the Louisiana Coast

Investigation of August 1980 Blowout and Fire, Lease OCS-G 2271 Vermilion Block 348, Gulf of Mexico Off the Louisiana Coast by Robert H. Darrow Michael J. Hebert Charles J. Schoennagel, Jr Daniel J. Bourgeois U. S. Geological Survey Open File Report 81-712 April 1981 Table of Contents I. Investigation and Report A. Authority ................................................. 1 B. Procedures................................................. 1 II. Introduction A. Background................................................. 1 B. Description of Incident.................................... 2 III. Findings A. Preliminary Activities..................................... 3 B. Loss of Wel1 Control....................................... 3 C. Explosion and Fire......................................... 4 0. Emergency Warning.......................................... 4 E. Abandonment of Platform.................................... 4 F. Injuries and Damage........................................ 4 IV. Conclusions A. Proximate Cause of Incident................................ 4 B. Proximate Cause of Explosion and Fire...................... 5 C. Cause of Injuries.......................................... 5 D. Contributing Causes........................................ 5 E. Evidence of Misconduct or Violations....................... B V. Recommendations A. Issuance of Proposed OCS Order 6........................... 5 B. Issuance of Safety Alert................................... 5 C. Review Maintenance Program................................. fi D. Case Closed............................................... -

Visiting Astronomers March 1981: 1I0vaisky/Chevalier, Veron, M

Visiting Astronomers March 1981: 1I0vaisky/Chevalier, Veron, M. P./Collin-Souffrin, Veron, P., Benvenuti, Simon/Kudritzki, Ahlin/ (October 1, 1980-ApriI1, 1981) Sundman, Ferlet/Bouchet, Gahm, de Loore/ Burger/van den Heuvel/van Paradijs. Observing time has now been allocated for period 26 (October 1, 1980 to April 1, 1981). As usual, the demand for telescope 1 m Photometrie Teleseope time was much greater than the time actually available. Oe!. 1980: AzzopardilVigneau/Lequeux/Maeder, Wlerick/ The following list gives the names of the visiting astronomers, Bouchet, ThelAlcaino, FitzGerald/Harris/Reed, by telescope and in chronological order. The complete list, with Koornneef, Schmidt/Engels/Schultz, Bouchet, dates, equipment and programme titles, is available from ESO/ Chincarini. Garehing. Nov. 1980: Chincarini, Westerlund/Lundgren, Wlerick/Bou chet, Koornneef, Fridlund/Nordh/Olofsson, Sol. 3.6 m Teleseope Dec. 1980: Sol, Schoembs/Stolz, Schnur/Mattila, van Woer Oct. 1980: D'Odorico, Swings/Surdej/Osmer, Tarenghi/ den/Danks, Bouchet, Groote/Kaufman n, Koes ter/Weidemann. Crane/Ellis/Kibblewhite/Peterson/Malin, Valen tijn, Wlerick/Bouchet, Lequeux/West/Schuster/ Jan. 1981: Koester/Weidemann, Wlerick/Bouchet, Petters Laustsen, Lindblad/Athanassou la/Jörsäter, The/ son, Geyer/Hänel/Nelles, Barbier/Remijn/The, Alcaino, Alcaino, Moorwood/Salinari/Shaver, Reipurth, FitzGerald/Harris/Reed, Dubois/Philip. Danks/Wamsteker, Fricke/Kollatschny/Schlei- eher. Feb. 1981: Dubois/Philip, Bastien, Bouchet, Epchtein/Gui bert/Q-Rieu/Turon/Lepine, Ap-Workgroup, Mel Nov. 1980: Fricke/Kollatschny/Schleicher, Pakull/Zuider nick/Terlevich. wijk, Westerlund/Lundgren/Richer, Lindblad/ Athanassoula/Jörsäter, Möllenhoff, Westerlund/ March 1981: Melnick/Terlevich, Ardeberg/Maurice, Veron, M. Lundgren/Richer, The/Alcaino, Alcaino, Denne P., Gahm, Moorwood/Salinari, Mauder. -

Country Term # of Terms Total Years on the Council Presidencies # Of

Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council Elected Members Algeria 3 6 4 2004 - 2005 December 2004 1 1988 - 1989 May 1988, August 1989 2 1968 - 1969 July 1968 1 Angola 2 4 2 2015 – 2016 March 2016 1 2003 - 2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 9 18 15 2013 - 2014 August 2013, October 2014 2 2005 - 2006 January 2005, March 2006 2 1999 - 2000 February 2000 1 1994 - 1995 January 1995 1 1987 - 1988 March 1987, June 1988 2 1971 - 1972 March 1971, July 1972 2 1966 - 1967 January 1967 1 1959 - 1960 May 1959, April 1960 2 1948 - 1949 November 1948, November 1949 2 Australia 5 10 10 2013 - 2014 September 2013, November 2014 2 1985 - 1986 November 1985 1 1973 - 1974 October 1973, December 1974 2 1956 - 1957 June 1956, June 1957 2 1946 - 1947 February 1946, January 1947, December 1947 3 Austria 3 6 4 2009 - 2010 November 2009 1 1991 - 1992 March 1991, May 1992 2 1973 - 1974 November 1973 1 Azerbaijan 1 2 2 2012 - 2013 May 2012, October 2013 2 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998 - 1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000 - 2001 March 2000, June 2001 2 Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council 1979 - 1980 October 1979 1 Belarus1 1 2 1 1974 - 1975 January 1975 1 Belgium 5 10 11 2007 - 2008 June 2007, August 2008 2 1991 - 1992 April 1991, June 1992 2 1971 - 1972 April 1971, August 1972 2 1955 - 1956 July 1955, July 1956 2 1947 - 1948 February 1947, January 1948, December 1948 3 Benin 2 4 3 2004 - 2005 February 2005 1 1976 - 1977 March 1976, May 1977 2 Bolivia 3 6 7 2017 - 2018 June 2017, October -

Gc(28)/Inf/220

GC(XXVIII)/INF/220 29 August 1984 International Atomic Energy Agency GENERAL Distr. GENERAL CONFERENCE Original: ENGLISH Item 12 of the provisional agenda (GC(XXVIII)/711) THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON THE PHYSICAL PROTECTION OF NUCLEAR MATERIAL Report of the Director General 1. In October 1983, at its twenty-seventh regular session, the General Conference adopted resolution GC(XXVII)/RES/415, in which it: (a) ex pressed the hope that the International Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material would enter into force at the earliest possible date and that it would obtain the widest possible adherence; and (b) requested the Director General to report to the General Conference at its next regular session on the signature and ratification status of the Convention. This report is being submitted to the Conference in response to that request. 2. By 31 August 1984, the Convention had been signed by 37 States and one international organization (EURATOM) and ratified by ten States (see Annex); since the twenty-seventh regular session of the General Conference, the Convention has been signed by Australia and ratified by Bulgaria and Hungary. For the Convention's entry into force 21 ratifications, acceptances or approvals are necessary. 3. On 15 June 1984, the Director General addressed a note verbale (N5.92.21 Circ.) to those Member States which had not yet become parties 84-04002 GC(XXVIII)/INF/ 220 page 2 to the Convention requesting information regarding the action which those Governments might take or were already taking with respect to the Convention. From the replies to the note verbale so far received, it is evident that a number of Governments are taking steps in accordance with their internal laws towards becoming parties to the Convention. -

GOVERNOR:Quie, Albert H

MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY Minnesota State Archives GOVERNOR: Quie, Albert H.: An Inventory of His Audio-Visual Materials OVERVIEW Agency: Minnesota. Governor (1979-1983 : Quie). Series Title: Audio-Visual Materials. Dates: 1978-1983. Abstract: Videotapes, audio tapes, photo albums, cassette recordings, and loose photographs, negatives, and slides documenting Quie’s inauguration and various activities as governor, particularly speeches, attendance at special events and governors’ conferences, public service announcements and forums, and Republican Party politics. Also a series of oral history interviews with Governor Quie and members of his staff. Quantity: 5.75 cubic feet (6 boxes). Location: See Detailed Description section for box locations. SCOPE AND CONTENTS The videotapes include coverage of Quie's 1979 inaugural address and a speech at Hamline University's 150th anniversary celebration (1979), an interview concerning the 1980 U. S. presidential election, highlights from the 1982 Midwest Governors' Conference, a Meet the Governor presentation (1979), and a guest appearance on a 1981 Duluth news program. There are also two "Reports to the People" (1980) and public service announcements for highway safety (1979), Indochinese refugee support (1979), the Independent Republican Party (1981), and 1982 governor's forums on crime, housing, mental health, soil conservation, and education. The audio tapes include a February 1980 press conference, while the cassette recordings include remarks by Quie and others at special events. The photograph albums cover the 1979 and 1980 National Governors' conferences, the 1980 Republican Governors Convention, and the 1980 and 1981 Midwest Governors' conferences. The loose photographs, negatives, and slides include a number of portraits of Governor Quie, Gretchen Quie, and Lieutenant Governor Lou Wangberg, including their "official" portraits and swearing-in ceremonies photographs; numerous publicity shots covering milk promotion, awards dinners and groundbreaking celebrations, and tours; Republican Party activities, with U. -

The London Gazette, Hth December 1980 17235

THE LONDON GAZETTE, HTH DECEMBER 1980 17235 DAVIES, Jeffrey, of 26 Heol Morfa, Briton Ferry, Neath BRENCH, Charles William, of no fixed abode, lately - in the county of West Glamorgan, Water Jet Operator, residing at 97 Oatlands Drive, Slough, Berks, and formerly Self Employed as a SUB-CONTRACTING previously at 55 Wexham Road, Slough aforesaid, Self- PAINTER. Court—NEATH AND PORT TALBOT. Employed LABOURER (described in the Receiving No. of Matter—& of 1975. Date of Order—8th July Order as C. W. Brench (male)). Court—SLOUGH. No. 1980. Nature of Order Made—Discharge granted. of Matter—40 of 1975. Date of Order—1st August 1980. Nature of Order Made—Bankrupt's discharge BAILEY, Gerald Anthony John (described in the Receiv- suspended one month, discharged 1st September 1980. ing Order as G. A. Bailey (male)), of 172 Gladstone Road, Northampton, Northamptonshire, unemployed, COLES, Georgina (married woman), 21 Gleneagles Tower, lately carrying on business under the style of "North- Flemming Road, Southall, Middlesex, housewife, lately ampton Building and Garden Construction", BUILDER. residing at 30 Frampton Court, Trowbridge, Wiltshire; Court—NORTHAMPTON. No. of Matter—33 of 1975. Court—SLOUGH. No. of Matter—63 of 1975. Date Date of Order—28th August 1980. Nature of Order of Order—1st August 1980. Nature of Order Made- Made—Discharge refused. Bankrupt discharged. BARNES, Jack, of Longham Cottage, Longham, Dereham, COLLINS, Christopher Maurice, 47 Grove Road, Windsor, Norfolk, ELECTRONICS ENGINEER. Court—NOR- Berkshire, VAN DRIVER, lately carrying on business WICH. No. of Matter—52 of 1975. Date of Order—12th under the name or style of "W. -

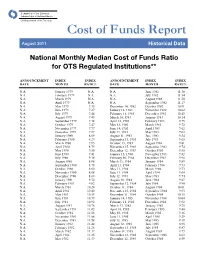

Historical Data

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks US Department of the Treasury Cost of Funds Report August 2011 Historical Data National Monthly Median Cost of Funds Ratio for OTS Regulated Institutions** ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX ANNOUNCEMENT INDEX INDEX DATE MONTH RATE% DATE MONTH RATE% N.A. January 1979 N.A. N.A. June 1982 11.38 N.A. February 1979 N.A. N.A. July 1982 11.54 N.A. March 1979 N.A. N.A. August 1982 11.50 N.A. April 1979 N.A. N.A. September 1982 11.17 N.A. May 1979 7.35 December 14, 1982 October 1982 10.91 N.A. June 1979 7.27 January 12, 1983 November 1982 10.62 N.A. July 1979 7.44 February 11, 1983 December 1982 10.43 N.A. August 1979 7.49 March 14, 1983 January 1983 10.14 N.A. September 1979 7.38 April 12, 1983 February 1983 9.75 N.A. October 1979 7.47 May 13, 1983 March 1983 9.72 N.A. November 1979 7.77 June 14, 1983 April 1983 9.62 N.A. December 1979 7.87 July 13, 1983 May 1983 9.62 N.A. January 1980 8.09 August 11, 1983 June 1983 9.54 N.A. February 1980 8.29 September 13, 1983 July 1983 9.65 N.A. March 1980 7.95 October 13, 1983 August 1983 9.81 N.A. April 1980 8.79 November 15, 1983 September 1983 9.74 N.A. May 1980 9.50 December 12, 1983 October 1983 9.85 N.A.