Border Rivers Community Profile: Irrigation Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Namoi River Salinity

Instream salinity models of NSW tributaries in the Murray-Darling Basin Volume 3 – Namoi River Salinity Integrated Quantity and Quality Model Publisher NSW Department of Water and Energy Level 17, 227 Elizabeth Street GPO Box 3889 Sydney NSW 2001 T 02 8281 7777 F 02 8281 7799 [email protected] www.dwe.nsw.gov.au Instream salinity models of NSW tributaries in the Murray-Darling Basin Volume 3 – Namoi River Salinity Integrated Quantity and Quality Model April 2008 ISBN (volume 2) 978 0 7347 5990 0 ISBN (set) 978 0 7347 5991 7 Volumes in this set: In-stream Salinity Models of NSW Tributaries in the Murray Darling Basin Volume 1 – Border Rivers Salinity Integrated Quantity and Quality Model Volume 2 – Gwydir River Salinity Integrated Quantity and Quality Model Volume 3 – Namoi River Salinity Integrated Quantity and Quality Model Volume 4 – Macquarie River Salinity Integrated Quantity and Quality Model Volume 5 – Lachlan River Salinity Integrated Quantity and Quality Model Volume 6 – Murrumbidgee River Salinity Integrated Quantity and Quality Model Volume 7 – Barwon-Darling River System Salinity Integrated Quantity and Quality Model Acknowledgements Technical work and reporting by Perlita Arranz, Richard Beecham, and Chris Ribbons. This publication may be cited as: Department of Water and Energy, 2008. Instream salinity models of NSW tributaries in the Murray-Darling Basin: Volume 3 – Namoi River Salinity Integrated Quantity and Quality Model, NSW Government. © State of New South Wales through the Department of Water and Energy, 2008 This work may be freely reproduced and distributed for most purposes, however some restrictions apply. Contact the Department of Water and Energy for copyright information. -

Dubbo Zirconia Project

Dubbo Zirconia Project Aquatic Ecology Assessment Prepared by Alison Hunt & Associates September 2013 Specialist Consultant Studies Compendium Volume 2, Part 7 This page has intentionally been left blank Aquatic Ecology Assessment Prepared for: R.W. Corkery & Co. Pty Limited 62 Hill Street ORANGE NSW 2800 Tel: (02) 6362 5411 Fax: (02) 6361 3622 Email: [email protected] On behalf of: Australian Zirconia Ltd 65 Burswood Road BURSWOOD WA 6100 Tel: (08) 9227 5677 Fax: (08) 9227 8178 Email: [email protected] Prepared by: Alison Hunt & Associates 8 Duncan Street ARNCLIFFE NSW 2205 Tel: (02) 9599 0402 Email: [email protected] September 2013 Alison Hunt & Associates SPECIALIST CONSULTANT STUDIES AUSTRALIAN ZIRCONIA LTD Part 7: Aquatic Ecology Assessment Dubbo Zirconia Project Report No. 545/05 This Copyright is included for the protection of this document COPYRIGHT © Alison Hunt & Associates, 2013 and © Australian Zirconia Ltd, 2013 All intellectual property and copyright reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1968, no part of this report may be reproduced, transmitted, stored in a retrieval system or adapted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to Alison Hunt & Associates. Alison Hunt & Associates RW CORKERY & CO. PTY. LIMITED AUSTRALIAN ZIRCONIA LTD Dubbo Zirconia Project Aquatic Ecology Final September 2013 SPECIALIST CONSULTANT STUDIES AUSTRALIAN ZIRCONIA LTD Part 7: Aquatic Ecology Assessment Dubbo Zirconia Project Report No. 545/05 SUMMARY Alison Hunt & Associates Pty Ltd was commissioned by RW Corkery & Co Pty Limited, on behalf of Australian Zirconia Limited (AZL), to undertake an assessment of aquatic ecology for the proposed development of the Dubbo Zirconia Project (DZP), which would be located at Toongi, approximately 25 km south of Dubbo in Central West NSW. -

Ken Hill and Darling River Action Group Inc and the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group

R. A .G TO THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN MURRAY DARLING BASIN ROYAL COMMISSION SUBMISSION BY: The Broken Hill and Darling River Action Group Inc and the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group. With the permission of the Executive and Members of these Groups. Prepared by: Mark Hutton on behalf of the Broken Hill and Darling River Action Group Inc and the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group. Chairman of the Broken Hill and Darling River Action Group and Co Administrator of the Broken Hill Menindee Lakes We Want Action Facebook Group Mark Hutton NSW Date: 20/04/2018 Index The Effect The Cause The New Broken Hill to Wentworth Water Supply Pipeline Environmental health Floodplain Harvesting The current state of the Darling River 2007 state of the Darling Report Water account 2008/2009 – Murray Darling Basin Plan The effect on our communities The effect on our environment The effect on Indigenous Tribes of the Darling Background Our Proposal Climate Change and Irrigation Extractions – Reduced Flow Suggestions for Improvements Conclusion References (Fig 1) The Darling River How the Darling River and Menindee Lakes affect the Plan and South Australia The Effect The flows along the Darling River and into the Menindee Lakes has a marked effect on the amount of water that flows into the Lower Murray and South Australia annually. Alought the percentage may seem small as an average (Approx. 17% per annum) large flows have at times contributed markedly in times when the Lower Murray River had periods of low or no flow. This was especially evident during the Millennium Drought when a large flow was shepherded through to the Lower Lakes and Coorong thereby averting what would have been a natural disaster and the possibility of Adelaide running out of water. -

Government Gazette of the STATE of NEW SOUTH WALES Number 112 Monday, 3 September 2007 Published Under Authority by Government Advertising

6835 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 112 Monday, 3 September 2007 Published under authority by Government Advertising SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT EXOTIC DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACT 1991 ORDER - Section 15 Declaration of Restricted Areas – Hunter Valley and Tamworth I, IAN JAMES ROTH, Deputy Chief Veterinary Offi cer, with the powers the Minister has delegated to me under section 67 of the Exotic Diseases of Animals Act 1991 (“the Act”) and pursuant to section 15 of the Act: 1. revoke each of the orders declared under section 15 of the Act that are listed in Schedule 1 below (“the Orders”); 2. declare the area specifi ed in Schedule 2 to be a restricted area; and 3. declare that the classes of animals, animal products, fodder, fi ttings or vehicles to which this order applies are those described in Schedule 3. SCHEDULE 1 Title of Order Date of Order Declaration of Restricted Area – Moonbi 27 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Woonooka Road Moonbi 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Anambah 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Muswellbrook 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Aberdeen 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – East Maitland 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Timbumburi 29 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – McCullys Gap 30 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Bunnan 31 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area - Gloucester 31 August 2007 Declaration of Restricted Area – Eagleton 29 August 2007 SCHEDULE 2 The area shown in the map below and within the local government areas administered by the following councils: Cessnock City Council Dungog Shire Council Gloucester Shire Council Great Lakes Council Liverpool Plains Shire Council 6836 SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT 3 September 2007 Maitland City Council Muswellbrook Shire Council Newcastle City Council Port Stephens Council Singleton Shire Council Tamworth City Council Upper Hunter Shire Council NEW SOUTH WALES GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No. -

Government Gazette No 63 of 16 June 2017 Government Notices GOVERNMENT NOTICES

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE – 16 June 2017 Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales Number 63 Friday, 16 June 2017 The New South Wales Government Gazette is the permanent public record of official notices issued by the New South Wales Government. It also contains local council and other notices and private advertisements. The Gazette is compiled by the Parliamentary Counsel’s Office and published on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) under the authority of the NSW Government. The website contains a permanent archive of past Gazettes. To submit a notice for gazettal – see Gazette Information. By Authority ISSN 2201-7534 Government Printer 2503 NSW Government Gazette No 63 of 16 June 2017 Government Notices GOVERNMENT NOTICES WaterNSW Prices for rural bulk water services from 1 July 2017 Determination Water Charge (Infrastructure) Rules 2010 (Cth) Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal Act 1992 (NSW) Determination June 2017 Water 2504 NSW Government Gazette No 63 of 16 June 2017 Government Notices © Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal of New South Wales 2017 This work is copyright. The Copyright Act 1968 permits fair dealing for study, research, news reporting, criticism and review. Selected passages, tables or diagrams may be reproduced for such purposes provided acknowledgement of the source is included. ISBN 978-1-76049-083-6 Deter 17-01 The Tribunal members for this review are: Dr Peter J Boxall AO, Chair Mr Ed Willett Ms Deborah Cope Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal of New South Wales -

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin Animals and Habitat the Basin Supports a Diverse Range of Plants and the Murray–Darling Basin Is Australia’S Largest Animals

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin animals and habitat The Basin supports a diverse range of plants and The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest animals. Over 350 species of birds (35 endangered), and most diverse river system — a place of great 100 species of lizards, 53 frogs and 46 snakes national significance with many important social, have been recorded — many of them found only in economic and environmental values. Australia. The Basin dominates the landscape of eastern At least 34 bird species depend upon wetlands in 1. 2. 6. Australia, covering over one million square the Basin for breeding. The Macquarie Marshes and kilometres — about 14% of the country — Hume Dam at 7% capacity in 2007 (left) and 100% capactiy in 2011 (right) Narran Lakes are vital habitats for colonial nesting including parts of New South Wales, Victoria, waterbirds (including straw-necked ibis, herons, Queensland and South Australia, and all of the cormorants and spoonbills). Sites such as these Australian Capital Territory. Australia’s three A highly variable river system regularly support more than 20,000 waterbirds and, longest rivers — the Darling, the Murray and the when in flood, over 500,000 birds have been seen. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth, Murrumbidgee — run through the Basin. Fifteen species of frogs also occur in the Macquarie and despite having one of the world’s largest Marshes, including the striped and ornate burrowing The Basin is best known as ‘Australia’s food catchments, river flows in the Murray–Darling Basin frogs, the waterholding frog and crucifix toad. bowl’, producing around one-third of the are among the lowest in the world. -

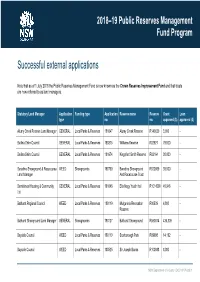

Successful External Applications

2018–19 Public Reserves Management Fund Program Successful external applications Note that as of 1 July 2018 the Public Reserves Management Fund is now known as the Crown Reserves Improvement Fund and that trusts are now referred to as land managers. Statutory Land Manager Application Funding type Application Reserve name Reserve Grant Loan type no. no. approved ($) approved ($) Alumy Creek Reserve Land Manager GENERAL Local Parks & Reserves 181647 Alumy Creek Reserve R140020 3,600 - Ballina Shire Council GENERAL Local Parks & Reserves 180875 Williams Reserve R82927 79,000 - Ballina Shire Council GENERAL Local Parks & Reserves 181674 Kingsford Smith Reserve R82164 30,000 - Baradine Showground & Racecourse WEED Showgrounds 180790 Baradine Showground R520059 38,500 - Land Manager And Racecourse Trust Barriekneal Housing & Community GENERAL Local Parks & Reserves 181646 Ella Nagy Youth Hall R1014508 40,946 - Ltd Bathurst Regional Council WEED Local Parks & Reserves 180119 Mulgunnia Recreation R80539 4,800 - Reserve Bathurst Showground Land Manager GENERAL Showgrounds 180127 Bathurst Showground R590074 435,309 - Bayside Council WEED Local Parks & Reserves 180110 Scarborough Park R69998 14,192 - Bayside Council WEED Local Parks & Reserves 180525 Sir Joseph Banks R100088 8,000 - NSW Department of Industry | DOC18/176333| 1 2018–19 Public Reserves Management Fund Program Statutory Land Manager Application Funding type Application Reserve name Reserve Grant Loan type no. no. approved ($) approved ($) Bayside Council WEED Local Parks & Reserves -

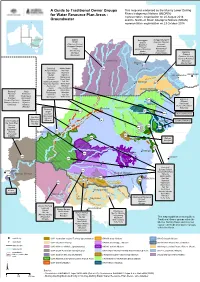

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti -

2019-20 Annual Statistics

Dumaresq-Barwon Border Rivers Commission Annual Statistics 2019-20 This report is a collation of statistical data provided by the New South Wales’ Department of Planning, Industry and Environment and WaterNSW; and Queensland’s Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy and Sunwater Ltd. The information contained has not been verified against independent sources. Dumaresq-Barwon Borders Rivers Commission – 2019-20 Annual Statistics Contents Water Infrastructure .............................................................................................................................. 1 Table 1 - Key features of Border Rivers Commission works ......................................................................... 1 Table 2 - Glenlyon Dam monthly storage volumes (megalitres) ................................................................... 3 Table 3 - Glenlyon Dam monthly releases / spillway flows (megalitres) ...................................................... 4 Table 4 - Glenlyon Dam recreation statistics ................................................................................................ 4 Resource allocation, sharing and use ...................................................................................................... 5 Table 5 – Supplemented / regulated1 and Unsupplemented / supplementary2 water entitlements and off- stream storages ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Table 6 - Water use from -

Functioning and Changes in the Streamflow Generation of Catchments

Ecohydrology in space and time: functioning and changes in the streamflow generation of catchments Ralph Trancoso Bachelor Forest Engineering Masters Tropical Forests Sciences Masters Applied Geosciences A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Earth and Environmental Sciences Trancoso, R. (2016) PhD Thesis, The University of Queensland Abstract Surface freshwater yield is a service provided by catchments, which cycle water intake by partitioning precipitation into evapotranspiration and streamflow. Streamflow generation is experiencing changes globally due to climate- and human-induced changes currently taking place in catchments. However, the direct attribution of streamflow changes to specific catchment modification processes is challenging because catchment functioning results from multiple interactions among distinct drivers (i.e., climate, soils, topography and vegetation). These drivers have coevolved until ecohydrological equilibrium is achieved between the water and energy fluxes. Therefore, the coevolution of catchment drivers and their spatial heterogeneity makes their functioning and response to changes unique and poses a challenge to expanding our ecohydrological knowledge. Addressing these problems is crucial to enabling sustainable water resource management and water supply for society and ecosystems. This thesis explores an extensive dataset of catchments situated along a climatic gradient in eastern Australia to understand the spatial and temporal variation -

Border Rivers and Moonie River Basins Healthy Waters

Healthy Waters Management Plan Queensland Border Rivers and Moonie River Basins Prepared to meet accreditation requirements under the Water Act 2007- Basin Plan 2012 Healthy Waters Management Plan: Queensland Border Rivers and Moonie River Basins Acknowledgement of the Traditional Owners of the Queensland Border Rivers and Moonie region The Department of Environment and Science (the department) would like to acknowledge and pay respect to the past and present Traditional Owners of the region and their Nations, and thank the representatives of the Aboriginal communities, including the Elders, who provided their knowledge of natural resource management throughout the consultation process. The department acknowledges that the Traditional Owners of the Queensland Border Rivers and Moonie basins have a deep cultural connection to their lands and waters. The department understands the need for recognition of Traditional Owner knowledge and cultural values in water quality planning. Prepared by: Department of Environment and Science. © State of Queensland, 2019. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. -

New South Wales Government Gazette No. 41 of 12 October

4321 Government Gazette OF THE STATE OF NEW SOUTH WALES Number 107 Friday, 12 October 2012 Published under authority by the Department of Premier and Cabinet LEGISLATION Online notification of the making of statutory instruments Week beginning 1 October 2012 THE following instruments were officially notified on the NSW legislation website (www.legislation.nsw.gov.au) on the dates indicated: Proclamations commencing Acts City of Sydney Amendment (Central Sydney Traffic and Transport Committee) Act 2012 No 47 (2012-498) — published LW 5 October 2012 Crime Commission Act 2012 No 66 (2012-499) — published LW 5 October 2012 Government Advertising Act 2011 No 35 (2012-500) — published LW 5 October 2012 Water Management Act 2000 No 92 (2012-495) — published LW 4 October 2012 Regulations and other statutory instruments Crime Commission Regulation 2012 (2012-501) — published LW 5 October 2012 Criminal Assets Recovery Amendment Regulation 2012 (2012-502) — published LW 5 October 2012 Government Advertising Regulation 2012 (2012-503) — published LW 5 October 2012 Police Amendment (Legal Advice Disclosure) Regulation 2012 (2012-504) — published LW 5 October 2012 Police Amendment (Targeted Tests) Regulation 2012 (2012-505) — published LW 5 October 2012 Water Management (Application of Act to Certain Water Sources) Proclamation (No 2) 2012 (2012-496) — published LW 4 October 2012 Water Management (General) Amendment (Water Sharing Plans) Regulation 2012 (2012-497) — published LW 4 October 2012 Water Sharing Plan for the Barwon-Darling Unregulated and