Mitzva 47 – Capital Punishment Rabbi Ian (Chaim) Pear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAMAOR Pesach 5775 / April 2015 HAMAOR 3 New Recruits at the Federation

PESACH 5775 / APRIL 2015 3 Parent Families A Halachic perspective 125 Years of Edmonton Federation Cemetery A Chevra Kadisha Seuda to remember Escape from Castelnuovo di Garfagnana An Insider’s A Story of Survival View of the Beis Din Demystifying Dinei Torah hamaor Welcome to a brand new look for HaMaor! Disability, not dependency. I am delighted to introduce When Joel’s parents first learned you to this latest edition. of his cerebral palsy they were sick A feast of articles awaits you. with worry about what his future Within these covers, the President of the Federation 06 might hold. Now, thanks to Jewish informs us of some of the latest developments at the Blind & Disabled, they all enjoy Joel’s organisation. The Rosh Beis Din provides a fascinating independent life in his own mobility examination of a 21st century halachic issue - ‘three parent 18 apartment with 24/7 on site support. babies’. We have an insight into the Seder’s ‘simple son’ and To FinD ouT more abouT how we a feature on the recent Zayin Adar Seuda reflects on some give The giFT oF inDepenDence or To of the Gedolim who are buried at Edmonton cemetery. And make a DonaTion visiT www.jbD.org a restaurant familiar to so many of us looks back on the or call 020 8371 6611 last 30 years. Plus more articles to enjoy after all the preparation for Pesach is over and we can celebrate. My thanks go to all the contributors and especially to Judy Silkoff for her expert input. As ever we welcome your feedback, please feel free to fill in the form on page 43. -

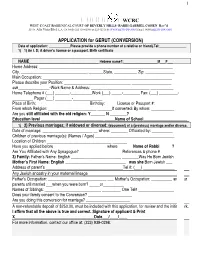

WCRC APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION)

1 WCRC WEST COAST RABBINICAL COURT OF BEVERLY HILLS- RABBI GABRIEL COHEN Rav”d 331 N. Alta Vista Blvd . L.A. CA 90036 323 939-0298 Fax 323 933 3686 WWW.BETH-DIN.ORG Email: INFO@ BETH-DIN.ORG APPLICATION for GERUT (CONVERSION) Date of application: ____________Please provide a phone number of a relative or friend).Tel:_______________ 1) 1) An I. D; A driver’s license or a passport. Birth certificate NAME_______________________ ____________ Hebrew name?:___________________M___F___ Home Address: ________________________________________________________________ City, ________________________________ _______State, ___________ Zip: ______________ Main Occupation: ______________________________________________________________ Please describe your Position: ________________________________ ___________________ ss#_______________-Work Name & Address: ____________________________ ___________ Home Telephone # (___) _______-__________Work (___) _____-________ Fax: (___) _________- __________ Pager (___) ________-______________ Place of Birth: ______________________ ___Birthday:______License or Passport #: ________ From which Religion: _______________________ _______If converted: By whom: ___________ Are you still affiliated with the old religion: Y_______ N ________? Education level ______________________________ _____Name of School_____________________ 1) 2) Previous marriages; if widowed or divorced: (document) of a (previous) marriage and/or divorce. Date of marriage: ________________________ __ where: ________ Officiated by: __________ Children -

Britain's Orthodox Jews in Organ Donor Card Row

UK Britain's Orthodox Jews in organ donor card row By Jerome Taylor, Religious Affairs Correspondent Monday, 24 January 2011 Reuters Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has ruled that national organ donor cards are not permissable, and has advised followers not to carry them Britain’s Orthodox Jews have been plunged into the centre of an angry debate over medical ethics after the Chief Rabbi ruled that Jews should not carry organ donor cards in their current form. London’s Beth Din, which is headed by Lord Jonathan Sacks and is one of Britain’s most influential Orthodox Jewish courts, caused consternation among medical professionals earlier this month when it ruled that national organ donor cards were not permissible under halakha (Jewish law). The decision has now sparked anger from within the Orthodox Jewish community with one prominent Jewish rabbi accusing the London Beth Din of “sentencing people to death”. Judaism encourages selfless acts and almost all rabbinical authorities approve of consensual live organ donorship, such as donating a kidney. But there are disagreements among Orthodox leaders over when post- mortem donation is permissible. Liberal, Reform and many Orthodox schools of Judaism, including Israel’s chief rabbinate, allow organs to be taken from a person when they are brain dead – a condition most doctors consider to determine the point of death. But some Orthodox schools, including London’s Beth Din, have ruled that a person is only dead when their heart and lungs have stopped (cardio-respiratory failure) and forbids the taking of organs from brain dead donors. As the current donor scheme in Britain makes no allowances for such religious preferences, Rabbi Sacks and his fellow judges have advised their followers not to carry cards until changes are made. -

Report of the Regulatory Board of Brit Milah in South Arica

REPORT OF THE REGULATORY BOARD OF BRIT MILAH IN SOUTH AFRICA (“THE REGULATORY BOARD”) 2016 - 2018 1 Background The Regulatory Board of Brit Milah in South Africa was established by Chief Rabbi Dr Warren Goldstein in 2016. The Regulatory Board acts in terms of the delegated authority of the Chief Rabbi and Head of the Beth Din (Court of Jewish Law), Rabbi Moshe Kurtstag. This report covers the activities of the Regulatory Board since inception in April 2016. The number of Britot reported are for the calendar years 2016 and 2017. The Regulatory Board is responsible for: 1.1 Ensuring the very highest standards of care and safety for all infants undergoing a Brit Milah and ensuring that this sacred and holy procedure is conducted according to strict Halachic principles (Jewish law); 1.2 The development of standardised guidelines, policies and procedures to ensure that the highest standards of safety in the performance of Brit Milah are maintained in South Africa; 1.3 Ensuring the appropriate registration, training, accreditation and continuing education of practising Mohalim (plural for Mohel, a person who is trained to perform a circumcision according to Jewish law); 1.4 Maintaining all records of Brit Milahs performed in South Africa; and 1.4 Fully investigating any concerns or complaints raised regarding Brit 1 Milah with the authority to recommend and to institute the appropriate remedial action. The current members of the Regulatory Board are: Dr Richard Friedland (Chairperson). Rabbi Dr Pinhas Zekry (Expert Mohel). Rabbi Anton Klein (Beth Din Representative). Dr Reuven Jacks (Medical Officer). Dr Joseph Spitzer (Mohel and Medical Adviser). -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

Jewish Estate Planning Handout Materials Are Available for Download Or Printing on the HANDOUT TAB on the Gotowebinar Console

Jewish Estate Planning Handout materials are available for download or printing on the HANDOUT TAB on the gotowebinar console. If the tab is not open click on that tab to open it and view the materials. 1 Jewish Estate Planning By: Mathew Hoffman, Esq.; Dr. Rabbi Henry Hasson; Rabbi Shlomo Weissmann; Jonathan I. Shenkman, MBA and Martin M. Shenkman, Esq. 2 Thank you to our sponsors InterActive Legal – Vanessa Kanaga – (321) 252-0100 – [email protected] 3 Thank you to our sponsors Halachic Organ Donor Society - “HODS” – For more information see www.hods.org – 521 5th Ave, New York, NY 10175 – (212) 213-5087 – To obtain a form donor card see https://hods.org/registration/ Bet Din of America – For more information see https://bethdin.org/ – 305 7th Ave 12th floor, New York, NY 10001 – (212) 807-9042 – For forms see http://bethdin.org/forms/ 4 General Disclaimer The information and/or the materials provided as part of this program are intended and provided solely for informational and educational purposes. None of the information and/or materials provided as part of this power point or ancillary materials are intended to be, nor should they be construed to be the basis of any investment, legal, tax or other professional advice. Under no circumstances should the audio, power point or other materials be considered to be, or used as independent legal, tax, investment or other professional advice. The discussions are general in nature and not person specific. Laws vary by state and are subject to constant change. Economic developments could dramatically alter the illustrations or recommendations offered in the program or materials. -

December 12 2015 SB.Pub

The Jewish Center SHABBAT BULLETIN DECEMBER 12, 2015 • PARSHAT MIKETZ , S HABBAT ROSH CHODESH AND CHANUKAH • 30 K ISLEV 5776 Mazal Tov to the Kaplan family on the occasion of Einav’s Bat Mitzvah EREV SHABBAT CHANUKAH V WELCOME TO OUR COMMUNITY SCHOLAR 4:11PM Candle lighting DR. E RICA BROWN 4:15PM Minchah (3 rd floor) 7:30-9:00PM Community Chanukah Oneg WHO IS JOINING US THIS SHABBAT Teen Chanukah Lounge Seudah Shlishit: Have the Hellenists Won? Dr.Jekyll and Rabbi Hyde SHABBAT Sunday Morning 9:30am ROSH CHODESH AND CHANUKAH VI When Yaakov Met Pharaoh: Genesis 47 as a Metaphor 7:30AM Hashkama Minyan (The Max and Marion Grill Beit Midrash) for Exile and Redemption Please note earlier time. 8:30AM Rabbi Israel Silverstein Mishnayot Class with Rabbi Yosie Levine YACHAD SHABBTON 9:00AM Shacharit (3 rd floor) 9:15AM Hashkama Shiur with Rabbi Noach Goldstein (Lower Level) SHABBAT , DECEMBER 18 9:15AM Young Leadership Minyan (The Max Stern Auditorium) The JC is proud to partner with Manhattan Day 9:30AM Sof Zman Kriat Shema School and the Orthodox Union as they host their 10:00AM Youth Groups, Under age 3, 3-4-year-olds and 5-6-year-olds: annual Yachad Shabbaton. Participants will join us Geller Youth Center; 2 nd -3rd graders, 4 th -6th graders: 7 th floor Special Chanukah Programs in Youth Groups for Kabbalat Shabbat followed by a com- Community Kiddush (The Max Stern Auditorium) munal Shabbat Dinner. Sponsorship and hospitality opportunities available. For WITH THANKS TO OUR KIDDUSH SPONSORS : more information and to get involved, Chaviva, Andrew, Barak & Vered Kaplan, in honor of their contact [email protected]. -

Nieuw Israelietisch Weekblad,—Op- Pede in Zinspeling Middelbare Scholiere, Wil in Tjespolitiek Tenach

Losse nrs. f 2,50 IN DIT NUMMER PAG. Arabische joden 2 Vrede Nu-concert 3 Opinie 5 niwneiuwisraelietischweekblad Inwijding Bussurn 7 Vrede in Cairo 8 Kunst 10 9 december 1983 / 3 tewet 5744 jrg. 119 nr. 14 Economie 11 meer verkoelden de relaties in juni 1982 na de inval van Israël in Liba- non. PRAGMATISCH Shamir wil explosie Premier Jitschak Shamir heeft de betrekkingen tijdens zijn bezoek In al haar verschrikkingen aan Washington gerepareerd. „Is- heeft de PLO weer bloedig toe- raël is een vrij en democratisch land. geslagen. De organisatie die als bus wreken Het is gevestigd in een belangrijk hoogste doel heeft de verdwij- Jeruzalem van Daar helpt het deel de wereld. ning van Israël, heeft duidelijk liet over de strategische samenwer- ons", zei de Amerikaanse minister laten weten zelf niet van het to- king tussen Israël en de Verenigde George Shultz van buitenlandse za- neel te zijn verdwenen, ondanks Staten en ondanks dat president ken in antwoord op de kritiek van de verwoestende uitwerking Hosni Mubarak van Egypte op- Arabische staten op het strategisch die Israël in Libanon op haar in- merkte dat het akkoord „verschrik- akkoord. En het State Department frastructuur heeft gehad. On- kelijk isvoor het vredesproces in het liet naar buiten brengen dat aan Jit- danks de verbanninguit Beiroet. Midden Oosten en het de vrienden schak Shamir en aan Moshe Arens Ondanks de maand na maand van de Verenigde Staten in een onder de aandacht is gebracht dat voordurende PLO-burgeroorlog plaatst", lijken moeilijke positie er het strategische akkoord ook van in de Bekaa-vallei en in Tripoli. -

To Download As A

DEPARTURES World Mizrachi runs several leadership programs to prepare rabbis, educators and shlichim to serve in communities around the world. Here we profile some of the families who are starting their shlichut, and some who have recently returned. Rav Ilan & Chana Brownstein Rav Chaim & Shira Metzger Rav Nechemya & Batya Rosenfeld White Plains, NY Toronto, Canada Nashville, Tennessee “We are so excited to be heading Chaim and Shira have just arrived for “We landed in Nashville, Tennessee, with our daughter, Emunah Shirah, for shlichut in Toronto, Canada. Chaim just a few weeks ago. During our shlichut as Directors of Youth Pro- will be a member of the Beit Midrash shlichut with Torah MiTzion, we will gramming at the Young Israel of White Zichron Dov (affiliated with YU and teach at the local school which serves Plains, in White Plains, NY. Although Torah MiTzion) and he will also serve all streams and promotes academic youth activities look a little different as Rabbinic Assistant at the BAYT excellence as well as a love for Israel. now with Corona, we’re excited to (Beth Avraham Yoseph of Toronto) in We also plan to hold chavrutas with make the best of our situation and Thornhill. Shira will be running informal adults in the community and to run create fun and engaging experiences education activities at Ulpanat Orot of small learning groups and classes in for our shul. Additionally, Chana will be Bnei Akiva Schools and coordinating the various synagogues. working as the Program Coordinator the women’s Beit Midrash for OU- “We are especially excited and looking at the Jewish Renaissance Experi- JLIC. -

THE BETH DIN: Jewish Law in the UK

THE BETH DIN: Jewish Law in the UK The Centre for Social Cohesion THE BETH DIN JEWISH COURTS IN THE UK The Centre for Social Cohesion Clutha House 10 Storey’s Gate London SW1P 3AY Tel: +44 (0)20 7222 8909 Fax: +44 (0)5 601527476 Email: [email protected] www.socialcohesion.co.uk The Centre for Social Cohesion Limited by guarantee. Registered in England and Wales: No. 06609071 2009 THE CENTRE FOR SOCIAL COHESION Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 Background 4 THE BETH DIN AND THE ARBITRATION ACT (1996) 6 Rules applicable to Arbitration tribunals 7 Arbitration awards 8 Safeguards under the Arbitration Act – 9 Consent Impartiality Enforcement by civil courts Remit of arbitration tribunals Recognition of religious courts 12 THE BETH DIN AS A RELIGIOUS AUTHORITY 13 Religious functions of the Beth Din 13 The Beth Din, Divorce and Family Law – 13 Divorce The Divorce (Religious Marriages) Act 2002 Mediation INTERPRETATIONS OF JEWISH LAW IN THE UK 18 Positions on key issues – 18 Divorce Conversion Jewish status Conclusion 21 Glossary 22 THE BETH DIN: JEWISH LAW IN THE UK 1 Executive Summary What is the Beth Din and what does it do? The Beth Din is a Jewish authority which offers members of the Jewish communities two separate services – civil arbitration and religious rulings. The Beth Din provides civil arbitration as an alternative to court action under the Arbitration Act (1996), which grants all British citizens the right to resolve civil disputes through arbitration. They also provide religious rulings on personal issues of faith which are voluntary, non-binding and limited to an individual‘s private status. -

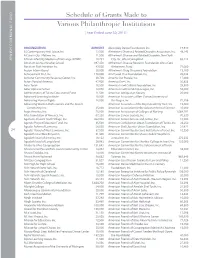

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

`P` Xb `P` “Ana Ger Ana: May a Convert to Judaism Serve on a Bet Din?” Rabbi Joseph H

`p` xb `p` “Ana Ger Ana: May a Convert to Judaism Serve on a Bet Din?” Rabbi Joseph H. Prouser Approved by the CJLS on May 30, 2012 by a vote of 19 in favor, none opposed and none abstaining. In favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, David Booth, Elliot Dorff, Baruch Frydman-Kohl, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Joshua Heller, David Hoffman, Adam Kligfeld, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jane Kanarek, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Jonathan Lubliner, Daniel Nevins, Paul Plotkin, Avram Reisner and Elie Spitz. She’eilah: Our colleague, Rabbi Shlomo Zacharow, a Mesader Gittin and Instructor at the Conservative Yeshiva in Jerusalem, has turned to the Joint Bet Din of the Conservative Movement1 for instructions regarding the permissibility of including a convert to Judaism among its members when he convenes a Bet Din for divorce proceedings. The question is occasioned by restrictive approaches to this matter recently articulated by the Orthodox Beth Din of America and, with particular force, by Beth Din member Rabbi Michael Broyde. May a convert to Judaism serve on a Bet Din? Teshuvah: Countless Gerei Tzedek -- sincere and devoted converts to Judaism -- labor daily on behalf of their fellow Jews as congregational and community leaders, as Jewish educators, as rabbis and cantors, as cherished, fully empowered members of the Jewish People, and as exemplars of Jewish religious practice. The blessings represented by the presence and active participation of converts in our communities is a powerful force in contemporary Judaism, but is hardly unique to the 21st Century.2 A significant percentage of the Tannaim, for example, were themselves converts or descended from converts.