Nantes (Fr) from Cranes to Elephant Laurent Lescop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note on Contributors

Note on Contributors Note on Contributors Sofia Apospori is currently a PhD candidate at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her research, which is supervised by Professor Helen Nicholson and advised by Dr. Colette Conroy, explores theatre for people with visual impairments. More specifically, it engages with the theoretical, aesthetic and ethical challenges that are implicated by the re-evaluation of performance space in reference to visual and non-visual perception respectively. Over the last two years, Sofia has been a visiting tutor in the Department of Drama and Theatre Studies, teaching Writing and Performance and Staging Histories. She holds a BA in Drama and Theatre Studies and an MA in Theatre (Applied Drama), both of which were awarded by Royal Holloway, University of London. Beatriz Cantinho is presently developing practice based research work as a PhD student in Dance/Philsophy at the Edinburgh College of Art. Her work focuses mainly on the mechanisms of image perception within aesthetics and performance art. The academic research as been presented at Edinburgh University, Chelsea College of Art, Cambridge University and the University of Surrey. Beatriz graduated from the Superior School of Dance at Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa. She took an intensive training course in Noh Theatre at the Kyoto Art Centre. She has completed a professional internship in the theatre company Royal de Luxe. Artistically for the past few years she has been developing work as a choreographer in projects such as Parde2, Scch…Um Ensaio Sobre o Silêncio, and Peça Veloz Corpo Volátil. She has also been involved in collaborative projects with artists from different disciplines with work that has been presented in Portugal, France, the UK, Germany, and Austria. -

A Case Study of the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Liverpool

Article The Cultural Legacy of a Major Event: A Case Study of the 2008 European Capital of Culture, Liverpool Yi-De Liu Graduate Institute of European Cultures and Tourism, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei 106, Taiwan; [email protected] Received: 23 June 2019; Accepted: 26 July 2019; Published: 26 July 2019 Abstract: Cultural legacy is a relatively neglected theme in event and sustainability studies, compared to economic or physical legacies with solid evidence. This article focuses on the experience of Liverpool as the 2008 European Capital of Culture. An evaluation ten years on can provide the basis for research on the long-term cultural legacy of a major event, as well as how to achieve sustainability through legacy planning. Five dimensions of cultural legacy are explored, including: Cultural agency and strategies, cultural network, cultural provision, cultural engagement, and cultural image. The results of the study show that the spill-over effect of culture can be achieved through thorough legacy planning. The most important lesson learned from Liverpool is to integrate the event into the city’s long-term and culture-led development, which yields a healthy and productive cultural climate. Keywords: event sustainability; cultural legacy; legacy planning; European Capital of Culture; Liverpool 1. Introduction In view of the economic, social and cultural impacts, more and more cities are competing to host major events. However, due to the short-lived and one-off nature, the event itself may not be sustainable. The sustainability of major events, or their legacy or long-term impact, has been the focus of discussion in recent years. -

Studies in International Performance Published in Association with The

Studies in International Performance Published in association with the International Federation of Theatre Research General Editors: Janelle Reinelt and Brian Singleton Culture and performance cross borders constantly, and not just the borders that define nations. In this new series, scholars of performance produce interactions between and among nations and cultures as well as genres, identities and imaginations. Inter-national in the largest sense, the books collected in the Studies in International Performance series display a range of historical, theoretical and critical approaches to the pan- oply of performances that make up the global surround. The series embraces ‘Culture’ which is institutional as well as improvised, underground or alternate, and treats ‘Performance’ as either intercultural or transnational as well as intracultural within nations. Titles include: Khalid Amine and Marvin Carlson THE THEATRES OF MOROCCO, ALGERIA AND TUNISIA Performance Traditions of the Maghreb Patrick Anderson and Jisha Menon (editors) VIOLENCE PERFORMED Local Roots and Global Routes of Conflict Elaine Aston and Sue-Ellen Case STAGING INTERNATIONAL FEMINISMS Matthew Isaac Cohen PERFORMING OTHERNESS Java and Bali on International Stages, 1905–1952 Susan Leigh Foster (editor) WORLDING DANCE Helen Gilbert and Jacqueline Lo PERFORMANCE AND COSMOPOLITICS Cross-Cultural Transactions in Australasia Helena Grehan PERFORMANCE, ETHICS AND SPECTATORSHIP IN A GLOBAL AGE Susan C. Haedicke CONTEMPORARY STREET ARTS IN EUROPE Aesthetics and Politics James Harding and Cindy Rosenthal (editors) THE RISE OF PERFORMANCE STUDIES Rethinking Richard Schechner’s Broad Spectrum Silvija Jestrovic and Yana Meerzon (editors) PERFORMANCE, EXILE AND ‘AMERICA’ Silvija Jestrovic PERFORMANCE, SPACE, UTOPIA Ola Johansson COMMUNITY THEATRE AND AIDS Ketu Katrak CONTEMPORARY INDIAN DANCE New Creative Choreography in India and the Diaspora Sonja Arsham Kuftinec THEATRE, FACILITATION, AND NATION FORMATION IN THE BALKANS AND MIDDLE EAST Daphne P. -

PRESS Releaseана16th AUGUST St Paul's Cathedral, Tate Modern

PRESS RELEASE 16TH AUGUST St Paul’s Cathedral, Tate Modern and the National Theatre join lineup of landmark locations and events for London’s Burning Artichoke’s contemporary art and ideas festival marking 350th anniversary of Great Fire of th th London 30 August 4 September 2016 Three more London landmarks, a live digital broadcast presented by Lauren Laverne and a talks programme inspired by major themes across the festival have been announced as part of LONDON’S BURNING, Artichoke’s contemporary art and ideas festival marking the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire of London. The series of spectacular art events, which are all free to the public, will take place in key th th sites across the City, Southbank and Bankside from 30 August 4 September 2016, marking this momentous event in London’s history and addressing its contemporary resonance with themes including displacement, disaster and the resilience of the urban metropolis. Artist Martin Firrell presents Fires of London, two new commissions either side of the River Thames. Fires Ancient will light up the south and east sides of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral with a fiery projection echoing both the catastrophic impact of the Great Fire of London on the Cathedral itself and the birth of the building designed by Christopher Wren that emerged, phoenixlike from the ashes. The projection will be visible from across the river and with a unique view from the terrace of One New Change. (Supported by Cheapside Business Alliance, RSA Insurance and Land Securities) On the other side of the river, Firrell’s Fires Modern will be projected onto the flytower of the National Theatre’s (NT’s) iconic Grade II listed building. -

Secours Aux Colons De Saint-Domingue. Indemnisation Des Colons Spoliés

Secours aux colons de Saint-Domingue. Indemnisation des colons spoliés Inventaire analytique (F/12/2740-F/12/2790, F/12/7627-F/12/7632/1) Par Ch. Douyère-Demeulenaere Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 2002 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_000199 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2012 par l'entreprise Numen dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) Sommaire Secours aux colons de Saint-Domingue. Indemnisation des colons spoliés. 422 A 427 ABBADIE, voir : DABBADIE. 427 ABBAYE (de L'), voir : L'ABBAYE (de). 427 ABBAYE-QUENIOT (de L'), voir : L'ABBAYE-QUENIOT (de). 427 ABEILLE (François Louis Honoré Barthélémy) colon réfugié de Saint-Domingue. 427 ABEILLE (Honoré Jean Adolphe) né à La Ciotat (Bouches-du-Rhône). ayant droit 427 de colon de Saint-Domingue. (dossier ABEILLE Jean Antoine) ABEILLE (Jean Antoine) né vers 1770, à La Ciotat (Bouches-du-Rhône) ; décédé 427 le 27 août 1826, à Lausanne (Suisse). colon réfugié de Saint-Domingue. ABEILLE (Jean Joseph André) né le 23 août 1756, à La Ciotat (Bouches-du- 427 Rhône). colon réfugié de Saint-Domingue. ABEL (Jean Baptiste) né le 13 mars 1762, au Cap-Français (Saint-Domingue) ; 427 décédé le 15 février 1834, à Paris. colon réfugié de Saint-Domingue. ABNOUR, voir : RICHARD d'ABNOUR. 427 ABZAC (Mme d') ayant droit de colon de Saint-Domingue. -

Artistic File L'enfant

L’ENFANT ©Christophe Loiseau [Animated materials, immersives installations] [Stage form, creation November 2018] [In situ form, creation February 2019] ©Christophe Loiseau L’Enfant (The Child) plunges us physically and substantially into the mystery at the heart of La mort de Tintagiles (The Death of Tintagiles), STATEMENT OF a play written by Maurice Maeterlinck in the late 19th century. Still very much engulfed in his immateriality, the «infant», from the Latin Infans, INTENT meaning «not having the faculty of speech», sits between worlds. He makes no distinction between the real and the imaginary, life and FOR death, and knows that the real is «merely one of the most transient ALL AGES aspects of infinite reality» as according to Artaud. OVER 14 The unexpected return of the infant, Tintagiles, to the devastated island strikes both joy and fear into the heart of his sister, Ygraine. Ygraine Duration 1h lives a life of subjection to an omnipresent yet invisible Queen, a figure who is preceded by a sense of imminent danger. Ygraine resolves to confront the dull and distant rumble (the dull and distant menace?) that destroys everything in its wake and threatens the child. In an act of rebellion, she upsets the established order, breaks down boundaries and enters that space impenetrable to the living, wherein she glimpses the infinite world of the shadow realm. « He is asleep in the other room. He was a little pale, he did not seem A funereal ode of cosmic proportions, the play is tantamount to well. The journey had tired him—he an act of regeneration, where the dynamic balance of existence is was a long time on the sea. -

Report ISACS Audience Research

Report into audiences for Street Arts, Circus and Spectacle in Ireland between June and September 2014 Kath Gorman Independent Consultant and Adviser Contents Pages 1. Background to the project 3 2. Purpose of the research 4 3. Research methodology 4 - 5 4. ISACS audience research 2014 5 5. Key findings 5 - 7 6. Interpretation of the findings 8 - 11 7. Recommendations 11 8. Appendices 12 - 14 2 1. Background to the project 1.1 Very little specific recent research has been carried out into audiences in the Street Arts, Circus and Spectacle sector in Ireland. The last published figures for attendances into people attending Circus, Street Arts or Spectacle can be found in the Arts Council Ireland’s 2006 survey The Public and the Arts. 1 The CASCAS report – Experiment Diversity with the Street Arts and Circus: An Overview of Circus and Street Arts in the UK and ROI provides an in-depth overview of the sector, with some reference to audiences for specific festivals (St Patrick’s Festival). 2 1.2 In April 2014 ISACS received a grant from Arts Council Ireland to support research into audiences for Street Arts, Circus and Spectacle in Ireland. Throughout 2015 – 2016 ISACS intend to enhance this research through gathering additional qualitative data on audiences. 1.3 The grant has enabled ISACS to work with Arts Audiences Ireland and the Arts Agency UK, who provided support and guidance. Debbie Wright in association with the University of Limerick, with input from Lucy Medlycott created a Street Arts Handbook, Audience Aware. 3 Audience Aware is a guide for collecting, understanding and using audience information. -

The Practice of Art and AI

Gerfried Stocker, Markus Jandl, Andreas J. Hirsch The Practice of Art and AI ARS ELECTRONICA Art, Technology & Society Contents Gerfried Stocker, Markus Jandl, Andreas J. Hirsch 8 Promises and Challenges in the Practice of Art and AI Andreas J. Hirsch 10 Five Preliminary Notes on the Practice of AI and Art 12 1. AI–Where a Smoke Screen Veils an Opaque Field 19 2. A Wide and Deep Problem Horizon– Massive Powers behind AI in Stealthy Advance 25 3. A Practice Challenging and Promising– Art and Science Encounters Put to the Test by AI 29 4. An Emerging New Relationship–AI and the Artist 34 5. A Distant Mirror Coming Closer– AI and the Human Condition Veronika Liebl 40 Starting the European ARTificial Intelligence Lab 44 Scientific Partners 46 Experiential AI@Edinburgh Futures Institute 48 Leiden Observatory 50 Museo de la Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero Centro de Arte y Ciencia 52 SETI Institute 54 Ars Electronica Futurelab 56 Scientific Institutions 59 Cultural Partners 61 Ars Electronica 66 Activities 69 Projects 91 Artists 101 CPN–Center for the Promotion of Science 106 Activities 108 Projects 119 Artists 125 The Culture Yard 130 Activities Contents Contents 132 Projects 139 Artists 143 Zaragoza City of Knowledge Foundation 148 Activities 149 Projects 155 Artists 159 GLUON 164 Activities 165 Projects 168 Artists 171 Hexagone Scène Nationale Arts Science 175 Activities 177 Projects 182 Artists 185 Kersnikova Institute / Kapelica Gallery 190 Activities 192 Projects 200 Artists 203 LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial 208 Activities -

CS LAB#6 May 25-26, 2021

CS LAB#6 May 25-26, 2021 C O - O R G A N I S E D B Y W I T H T H E S U P P O R T O F Introduction For the past year, the world and environment we were living in has been severely shaken by the global pandemic. We have been deprived of our reference points, of fundamental liberties, challenged in our capacity to endure, stand, accept and cope with an unprecedented situation impacting both the professional and personal realms. In the end, we had no choice but to adapt, reinvent ourselves, our ways of life and our working practices in order to move forward. More than ever over the course of the 21st century, we have been drawn to adapt to new circumstances, realities and, ultimately, to venture into some unknown grounds and face uncertainty, along with the anxiety and doubts it brought about. But concretely how did we navigate through this upheaval? What does it say about our resilience? Looking at the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS), from Hungarian- Canadian endocrinologist Hans Selye, we’ve tried in the framework of the CS LAB#6, to reproduce its stages: Alarm-Reaction, Resistance and Exhaustion, as a way to conduct experiences and stimulate thoughts on how our body and mind adapt to the stress labyrinth we are now crossing, as a deeply impacted sector, and as individuals. During two days, we invite you to experiment collectively this process and to reflect on the notions of adaptability, mental health and care. Let's observe the way our bodies and minds react to such stimuli, let's learn from it to better apprehend how we function and respond as human beings. -

26 Ship-Breaking.Com

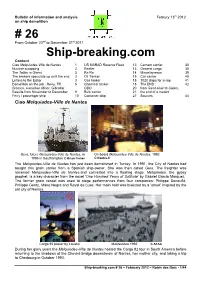

Bulletin of information and analysis Februry 13th 2012 on ship demolition # 26 From October 22nd to December 31st 2011 Ship-breaking.com Content Ciao Melquiades-Ville de Nantes 1 US MARAD Reserve Fleet 13 Cement carrier 30 Nuclear scrapping 2 Reefer 13 General cargo 30 The Tellier in Ghent 3 Ro Ro 14 Miscellaneous 39 The brokers speculate up until the end 3 Oil Tanker 15 Car carrier 40 Letters to the Editor 3 Gas tanker 18 1020 ships for scrap 41 Demolition on the job : Rena, TK 5 Chemical tanker 18 The END : 42 Bremen, Canadian Miner, Gibraltar OBO 20 from Saint-Clair to Salam, Results from November to December 9 Bulk carrier 21 the end of a mutant Ferry / passenger ship 10 Container ship 27 Sources 44 Ciao Melquiades-Ville de Nantes Gera, future Melquiades-Ville de Nantes, in On board Melquiades-Ville de Nantes, 1992 1986 in Southampton © Brian Fisher © Nantes.fr The Melquiades-Ville de Nantes has just been demolished in Turkey. In 1991, the City of Nantes had bought this grain carrier from a Spanish ship-owner. She was then called Gera. The freighter was renamed Melquiades-Ville de Nantes and converted into a floating stage. Melquiades, the gypsy prophet, is a key character from the novel 'One Hundred Years of Solitude’ by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The former grain vessel was used to stage performances from four companies: Philippe Decouflé, Philippe Genty, Mano Negra and Royal de Luxe. Her main hold was bisected by a ‘street’ inspired by the old city of Nantes. Cargo 92 poster by Loustal Montevideo 1992 © AFAA During her glory years the Melquiades-Ville de Nantes hosted the Cargo 92 tour in South America before returning to the shadows of the Cheviré bridge downstream of Nantes, her mother city, and taking a trip to Cherbourg in October 1993. -

Art Throughout the City, Exhibitions, Performances, Celebrations

AA SUMMERSUMMER ININ LELE HAVREHAVRE 20172017 ART THROUGHOUT THE CITY, EXHIBITIONS, PERFORMANCES, CELEBRATIONS PRESS KIT © OTAH PRESS KIT 2 PRESS KIT TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Foreword 5 PART 1 1517-2017: THE 500TH ANNIVERSARY OF LE HAVRE From the birth of Le Havre through its opening toward the world 7 From reconstruction to its World Heritage designation by UNESCO, Le Havre: Modern City 9 A Le Havre to (re)discover 11 A growing cultural influence 14 A bold city undergoing transformation 18 PART 2 A SUMMER IN LE HAVRE 2017 A Summer in Le Havre - Artists play the city 24 A Summer in Le Havre - The call from abroad 36 An ambitious global approach to a sustainable and environmentally responsible event 38 The dynamism of economic actors from the surrounding territory 40 PART 3 PRACTICAL INFORMATION Accessibility 42 Press Images 44 Contacts 45 A SUMMER A SUMMER IN LE HAVRE IN LE HAVRE 2017 2017 PRESS KIT 4 PRESS KIT 5 FOREWORD The chance to celebrate a 500th anniversary is a rare one — and in 2017, Le Havre has this chance! A chance to take a new look at our city — a look that will perhaps prove sur- prising. A chance to tell the world what we are and what we can do. 2017 will also mark a celebration of our identity. A happy identity, which does not revel in regrets of the past; an identity built from courage; an identity that looks lucidly on the glories and the shadows of the past; on the powers as well as the challenges of the present — but an optimistic identity, the porter of future projects. -

La Scène Artistique Nantaise, Levier De Son Développement Économique Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux

La scène artistique nantaise, levier de son développement économique Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux To cite this version: Dominique Sagot-Duvauroux. La scène artistique nantaise, levier de son développement économique. Nantes, la Belle Eveillée, le pari de la culture, Les éditions de l’attribut, pp.95-107, 2010. halshs- 00456982 HAL Id: halshs-00456982 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00456982 Submitted on 16 Feb 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. La scène artistique nantaise, levier de son développement économique « En vingt ans, Nantes est devenue une ville majeure au développement impressionnant. À l’origine de ce succès, une activité culturelle bouillonnante qui a su redonner vie à toute une cité ». C’est ainsi que le magazine Le Point du 24 avril 2008 introduisait son classement des villes « où l’on vit le mieux en France » qui plaçait Nantes, pour la troisième fois, en tête du palmarès. Depuis les années deux mille, Nantes apparaît en effet au premier rang de nombreux classements censés mesurer l’attractivité d’une ville ou le bien-être de ses habitants. De fait, de l’extérieur, Nantes donne l’image d’une ville dynamique, agréable à vivre (malgré un climat… humide et un patrimoine architectural moins riche (malgré son château) que ses consoeurs de Bordeaux, Toulouse, Montpellier ou Strasbourg.