Report on the Progress of Implementing in Bulgaria the White Paper on Corporate Governance in South East Europe – April 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report Amending ITS on Main Indices and Recognised Exchanges

Final Report Amendment to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1646 11 December 2019 | ESMA70-156-1535 Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 4 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 3 Main indices ................................................................................................................... 6 3.1 General approach ................................................................................................... 6 3.2 Analysis ................................................................................................................... 7 3.3 Conclusions............................................................................................................. 8 4 Recognised exchanges .................................................................................................. 9 4.1 General approach ................................................................................................... 9 4.2 Conclusions............................................................................................................. 9 4.2.1 Treatment of third-country exchanges .............................................................. 9 4.2.2 Impact of Brexit ...............................................................................................10 5 Annexes ........................................................................................................................12 -

Portfolio Optimization Analysis of Federation of Euro-Asian Stock Exchances (FEAS)

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2003 Portfolio optimization analysis of federation of Euro-Asian stock exchances (FEAS) Selim Larlar Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Corporate Finance Commons Recommended Citation Larlar, Selim, "Portfolio optimization analysis of federation of Euro-Asian stock exchances (FEAS)" (2003). Theses Digitization Project. 2365. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2365 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PORTFOLIO OPTIMIZATION ANALYSIS OF FEDERATION OF ' EURO-ASIAN STOCK EXCHANGES (FEAS) A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Business Administration Selim Larlar December 2003 PORTFOLIO OPTIMIZATION ANALYSIS OF FEDERATION OF EURO-ASIAN STOCK EXCHANGES (FEAS) i A Project I Presented to the ! Faculty of i California State University, San Bernardino I t I I i by Selim Larlar December 2003 Date ABSTRACT Institutional and individual investors all around the I globe are looking for different ways to diversify their I stock portfolio. This thesis will give them a chance to i understand the difference between Euro-Asian stock market i portfolios and the S&P 500. This thesis will also compare I performance analyses among ten founding members of the Federation of Euro-Asian Stock Exchanges (FEAS), the S&P 500 Indey, the Ten Composite Index and four sample portfolios, consisting of the ten founding member countries of FEAS and S&P 500. -

The List of Approved Stock Exchanges

November 9, 2018 The following stock exchanges are approved by the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority for purposes of the Regulatory Laws pursuant to the Authority’s Regulatory Policy – Approved Stock Exchanges. Note: This list is for illustrative purposes only and is subject to change. To verify whether a stock exchange is approved by the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority, please refer to the Regulatory Policy – Approved Stock Exchanges. Amman Stock Exchange Deutsche Borse Athens Exchange Dusseldorf Stock Exchange Australian Securities Exchange EDX London Barbados Stock Exchange Eurex BATS Exchange Euronext Bayerische Borse AG Fukuoka Stock Exchange* Berlin Stock Exchange Gibraltar Stock Exchange Bermuda Stock Exchange Hong Kong Exchange and Clearing BM&F Bovespa Indonesia Stock Exchange BME Spanish Exchanges Intercontinental Exchange BOAG Borsen AG International Securities Exchange Bolsa de Comercio de Buenos Aires Irish Stock Exchange Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago Istanbul Stock Exchange Bolsa de Valores de Caracas* Jamaica Stock Exchange Bolsa de Valores de Colombia JASDAQ Bolsa de Valores de Lima Johannesburg Stock Exchange Bombay Stock Exchange Korea Stock Exchange Borsa Italiana SPA London Stock Exchange Bratislava Stock Exchange Ljubljana Stock Exchange Bucharest Stock Exchange Luxembourg Stock Exchange Budapest Stock Exchange Madrid Stock Exchange Bulgarian Stock Exchange Malaysia Stock Exchange Cayman Islands Stock Exchange Malta Stock Exchange Channel Islands Stock Exchange* Mexican Stock Exchange Chicago Board Options Exchange -

Doing Data Differently

General Company Overview Doing data differently V.14.9. Company Overview Helping the global financial community make informed decisions through the provision of fast, accurate, timely and affordable reference data services With more than 20 years of experience, we offer comprehensive and complete securities reference and pricing data for equities, fixed income and derivative instruments around the globe. Our customers can rely on our successful track record to efficiently deliver high quality data sets including: § Worldwide Corporate Actions § Worldwide Fixed Income § Security Reference File § Worldwide End-of-Day Prices Exchange Data International has recently expanded its data coverage to include economic data. Currently it has three products: § African Economic Data www.africadata.com § Economic Indicator Service (EIS) § Global Economic Data Our professional sales, support and data/research teams deliver the lowest cost of ownership whilst at the same time being the most responsive to client requests. As a result of our on-going commitment to providing cost effective and innovative data solutions, whilst at the same time ensuring the highest standards, we have been awarded the internationally recognized symbol of quality ISO 9001. Headquartered in United Kingdom, we have staff in Canada, India, Morocco, South Africa and United States. www.exchange-data.com 2 Company Overview Contents Reference Data ............................................................................................................................................ -

Over 100 Exchanges Worldwide 'Ring the Bell for Gender Equality in 2021' with Women in Etfs and Five Partner Organizations

OVER 100 EXCHANGES WORLDWIDE 'RING THE BELL FOR GENDER EQUALITY IN 2021’ WITH WOMEN IN ETFS AND FIVE PARTNER ORGANIZATIONS Wednesday March 3, 2021, London – For the seventh consecutive year, a global collaboration across over 100 exchanges around the world plan to hold a bell ringing event to celebrate International Women’s Day 2021 (8 March 2020). The events - which start on Monday 1 March, and will last for two weeks - are a partnership between IFC, Sustainable Stock Exchanges (SSE) Initiative, UN Global Compact, UN Women, the World Federation of Exchanges and Women in ETFs, The UN Women’s theme for International Women’s Day 2021 - “Women in leadership: Achieving an equal future in a COVID-19 world ” celebrates the tremendous efforts by women and girls around the world in shaping a more equal future and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Women leaders and women’s organizations have demonstrated their skills, knowledge and networks to effectively lead in COVID-19 response and recovery efforts. Today there is more recognition than ever before that women bring different experiences, perspectives and skills to the table, and make irreplaceable contributions to decisions, policies and laws that work better for all. Women in ETFs leadership globally are united in the view that “There is a natural synergy for Women in ETFs to celebrate International Women’s Day with bell ringings. Gender equality is central to driving the global economy and the private sector has an important role to play. Our mission is to create opportunities for professional development and advancement of women by expanding connections among women and men in the financial industry.” The list of exchanges and organisations that have registered to hold an in person or virtual bell ringing event are shown on the following pages. -

List of Approved Regulated Stock Exchanges

Index Governance LIST OF APPROVED REGULATED STOCK EXCHANGES The following announcement applies to all equity indices calculated and owned by Solactive AG (“Solactive”). With respect to the term “regulated stock exchange” as widely used throughout the guidelines of our Indices, Solactive has decided to apply following definition: A Regulated Stock Exchange must – to be approved by Solactive for the purpose calculation of its indices - fulfil a set of criteria to enable foreign investors to trade listed shares without undue restrictions. Solactive will regularly review and update a list of eligible Regulated Stock Exchanges which at least 1) are Regulated Markets comparable to the definition in Art. 4(1) 21 of Directive 2014/65/EU, except Title III thereof; and 2) provide for an investor registration procedure, if any, not unduly restricting foreign investors. Other factors taken into account are the limits on foreign ownership, if any, imposed by the jurisdiction in which the Regulated Stock Exchange is located and other factors related to market accessibility and investability. Using above definition, Solactive has evaluated the global stock exchanges and decided to include the following in its List of Approved Regulated Stock Exchanges. This List will henceforth be used for calculating all of Solactive’s equity indices and will be reviewed and updated, if necessary, at least annually. List of Approved Regulated Stock Exchanges (February 2017): Argentina Bosnia and Herzegovina Bolsa de Comercio de Buenos Aires Banja Luka Stock Exchange -

Public Listed Company in Bulgaria

Public Listed Company in Bulgaria The Bulgaria Stock Exchange operates in Sofia and was originally founded as Sofia Stock Exchange on April 1914 and it was re-established in 1991, after ceasing its operations during World War II. A Joint Stock Company (JSC) in Bulgaria is registered on the Register of the Public Companies as a Public Listed Company, the founders of which may be physical or legal persons of any nationality. Its Board of Directors must consist of at least 3 and not more than 9 persons. Its shares are traded on the Bulgarian Stock Exchange and are always dematerialized, registered and managed by the Central Depository. The minimum estimated value of the assets of a JSC in Bulgaria should 500.000 BGN. In the event where the estimated value falls below of this amount, then the Company ceases to be Public. Public Listed Companies, in general, enjoy the benefit of limited scrutiny due to their status of being listed in Stock Exchanges and in certain cases they can receive exemptions from reporting requirements under local regulations. The majority of Money Laundering Legislation around the world categorizes them as low-risk clients and the Due Diligence and KYC requirements for Public Listed Companies are very limited: in some instances may not even exist. Our Services: • Set up of a Public Bulgarian Company, according to the requirements of the legislation, in order for it to be listed on the Bulgaria Stock Exchange. • Drafting the constitutional documentation and the memorandum. • Assistance for completing and preparing the application, according to the current legislation and regulations. -

Northern Trust Emea Order Execution Policy

NORTHERN TRUST EMEA ORDER EXECUTION POLICY For Professional Clients of the following Northern Trust entities: • Northern Trust Global Services SE, and its branches • Northern Trust Securities LLP, and its branches • The Northern Trust Company, London branch Publication date: 1 January 2021 Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 A. Purpose of this policy .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 B. What is Best Execution? ............................................................................................................................................................................... 3 POLICY SCOPE ..................................................................................................................................................................... 4 A. Northern Trust entities subject to this Policy ................................................................................................................................................. 4 B. Types of Clients ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 C. Activities ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Herefore Need to Recognise and Congratulate Them on Their Successes to Date

Press Release, Brussels, 9 June 2021 Launch of the European Small and Mid-Cap Awards 2021 The 9th edition of the European Small and Mid-Cap Awards will take place in November 2021 during the European Commission’s SME Week in Portorož, Slovenia. Small and mid-cap companies are vitally important in supporting the European economy. Equity is needed to buffer exogenous shocks and will be needed more than ever following the recent crisis so that public equity capital markets can perform to the best of their ability in helping businesses refinance their growth once the situation has subsided. Our Awards this year are even more significant as it is exactly these types of companies that will be key to re-equitising the European economy. We therefore need to recognise and congratulate them on their successes to date. EuropeanIssuers, the Federation of European Securities Exchanges (FESE) and the European Commission are delighted to announce that the following companies have been recognised within their national jurisdictions as the most outstanding listed companies across five categories: Nominations for the category Rising Star: • Almagro Capital listed on BME • Bilot PLC listed on Nasdaq Helsinki • Dadelo SA listed on Warsaw Stock Exchange • Ecomiam listed on Euronext • FOM Technologies listed on Nasdaq First North Growth Market Nominations for the category Star of 2021: • Aluflexpack AG listed on SIX Swiss Exchange • Compleo Charging Solutions AG listed on Deutsche Börse AG • eMan AS listed on Prague Stock Exchange • Entersoft SA listed on Athens Stock Exchange • Labomar SPA listed on Borsa Italiana • LeadDesk Oyj listed on Nasdaq Helsinki • Making Science listed on BME • Nacon SA listed on Euronext Nominations for the category International Star: • CZG - Česká zbrojovka Group SE listed on Prague Stock Exchange • Meritus ulaganja d.d. -

Presented by Capital Lounge Gmbh

PRESENTED BY CAPITAL LOUNGE GMBH dated April 2020 THE STOCK EXCHANGES OF THE BALKANS 3 THE STOCK EXCHANGES OF THE BALKANS 3 THE BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE 6 DEVELOPMENT 8 SET-UP 13 BGBX40 19 BEAM 61 PERFORMANCE 74 INDUSTRY SECTORS 70 COSTS 74 APPENDIX 76 76 THE BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE presented by Capital Lounge SET-UP : THE STRUCTURE OF THE BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE THE STOCK EXCHANGES OF THE BALKANS THE BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE presented by Capital Lounge 3 OVERVIEW : THE STOCK EXCHANGES OF THE BALKANS EXCHANGE BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA BULGARIA CROATIA GREECE HUNGARY FOUNDATION 2001 1991/1918 1907 1876 1864 EQUITIES 863 310 101 296 46 EXCHANGE MACEDONIA MONTENEGRO ROMANIA SERBIA SLOVENIA FOUNDATION 1995 1993 1839 1894 1989 EQUITIES 368 296 400 488 89 THE BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE presented by Capital Lounge 4 OVERVIEW : THE STOCK EXCHANGES OF THE BALKANS The accumulated Market Capitalization of all included Stock Exchanges sums up to 113,2 billion Euro. Bulgaria ranks with a Market Capitalization of almost 13 billion Euro in the centre (rank five) of all ten Stock Exchanges. The biggest exchange is the Athens Exchange Group (Greece) with a Market Capitalization of more than 30 billion Euro. Romania is on rank two with a Market Capitalization of close to 20 billion Euro. 35.000.000.000 € 30.000.000.000 € 25.000.000.000 € 20.000.000.000 € 15.000.000.000 € 10.000.000.000 € 5.000.000.000 € 0 € BOSNIA & BULGARIA CROATIA GREECE HUNGARY MACEDONIA MONTENEGRO ROMANIA SERBIA SLOVENIA HERZEGOVINA THE BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE presented by Capital Lounge 5 SET-UP : THE STRUCTURE OF THE BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE THE BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE THE BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE presented by Capital Lounge 6 INTRODUCTION : THE BULGARIAN STOCK EXCHANGE The history of the Bulgarian capital market dates back from the beginning of the 20th century. -

The Problem with European Stock Markets

THE PROBLEM WITH EUROPEAN STOCK MARKETS Analysis of the fragmented stock exchange landscape in Europe, how it is holding back growth in capital markets – and what we can do about it March 2021 by William Wright & Eivind Friis Hamre SUMMARY It is not new news that Europe has a complex patchwork of equity markets, stock exchanges and post-trade infrastructure, but this short paper paints this problem in particularly stark terms. The genesis of this paper came from two simple thought experiments: first, can we draw a diagram of the structure of European equity markets on one page? And second, what would the US stock market look like if every state has its own stock exchange? If you read nothing else in this report, please look at the map of the US market on page three and the diagram of European equity markets on page six. Here is a quick summary of this paper: > The elephant in the room The complex patchwork of European equity markets is a huge obstacle to building bigger and better capital markets at a time when the European economy needs them more than ever. We can tinker at the edges with the detail of regulation, but so as long as Europe has 22 different stock exchange groups operating 35 different exchange for listings, 41 exchanges for trading, and nearly 40 different CCPs and CSDs, not much will change. > Punching below its weight The European equity market is less than half the size of the US but has three times as many exchange groups; more than 10 times as many exchanges for listings; more than twice as many exchanges for trading; and roughly 20 times as many post-trade infrastructure providers. -

List of Trading Floor Identifier for Emissions

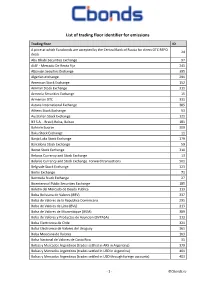

List of trading floor identifier for emissions Trading floor ID A price at which Eurobonds are accepted by the Central Bank of Russia for direct OTC REPO 24 deals Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange 97 AIAF - Mercado De Renta Fija 241 Albanian Secuities Exchange 395 Algerian exchange 291 American Stock Exchange 152 Amman Stock Exchange 311 Armenia Securities Exchange 15 Armenian OTC 331 Astana International Exchange 385 Athens Stock Exchange 53 Australian Stock Exchange 121 B3 S.A. - Brasil, Bolsa, Balcao 181 Bahrain Bourse 309 Baku Stock Exchange 11 Banja Luka Stock Exchange 179 Barcelona Stock Exchange 59 Beirut Stock Exchange 310 Belarus Currency and Stock Exchange 13 Belarus Currency and Stock Exchange. Forward transactions 501 Belgrade Stock Exchange 123 Berlin Exchange 71 Bermuda Stock Exchange 27 Bicentennial Public Securities Exchange 185 Boletin del Mercado de Deuda Publica 113 Bolsa Boliviana de Valores (BBV) 337 Bolsa de Valores de la Republica Dominicana 295 Bolsa de Valores de Lima (BVL) 213 Bolsa de Valores de Mozambique (BVM) 389 Bolsa de Valores y Productos de Asuncion (BVPASA) 313 Bolsa Electronica de Chile 321 Bolsa Electronica de Valores del Uruguay 361 Bolsa Mexicana de Valores 103 Bolsa Nacional de Valores de Costa Rica 31 Bolsas y Mercados Argentinos (trades settled in ARS in Argentina) 379 Bolsas y Mercados Argentinos (trades settled in USD in Argentina) 401 Bolsas y Mercados Argentinos (trades settled in USD through foreign accounts) 403 - 1 - ©Cbonds.ru Trading floor ID BondSpot 69 Borsa Istanbul (International Bonds