The World of Putting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alpine the Monument

THE ALPINE THE ALPINE Hole 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Out 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Total Brown 413 372 175 412 506 451 177 577 415 3498 404 178 514 420 411 457 423 178 562 3547 7045 Purple 403 366 170 397 498 433 177 563 415 3422 404 178 514 412 411 423 412 161 538 3453 6875 Orange 377 340 164 382 479 403 169 552 369 3235 390 146 499 404 387 403 387 145 505 3266 6501 Blue 377 340 164 364 479 387 147 552 350 3160 390 146 499 338 357 381 344 145 505 3105 6265 ANDICAP INITIALS H Green 365 314 152 364 448 387 147 511 350 3038 376 138 472 338 357 381 344 135 462 3003 6041 NET SCORE Silver 256 238 132 298 416 286 110 457 259 2452 342 138 445 319 319 325 239 121 383 2631 5083 Par 4 4 3 4 5 4 3 5 4 36 4 3 5 4 4 4 4 3 5 36 72 +/- THE ALPINE Stroke Men 5 13 17 1 15 7 11 9 3 6 16 14 2 8 10 4 18 12 Index Women 15 5 11 7 1 9 17 3 13 6 14 12 2 10 8 18 16 4 THE MONUMENT Scorer_________________________________ Attest__________________ Date____________________ Tees Brown Purple Orange Blue Green Silver Josh Richter Played Director of Golf Kurt Fisher Golf Course PIN PLACEMENT Casey Powers Superintendent Head PGA Professional RED = FRONT | WHITE = CENTER | YELLOW = BACK 20M / 20 THE MONUMENT THE MONUMENT The Monument Hole 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Out 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 In Total This course pays tribute to some of America's most 553 370 170 395 517 314 428 440 198 3385 551 386 454 227 557 415 350 232 407 3579 6964 Brown accomplished and memorable golfers. -

2200 Year Old Mathematical Theory Combines with Space Age Computer ® Design and CNC Manufacturing to Produce the Putting Arc

2200 year old mathematical theory combines with space age computer ® design and CNC manufacturing to produce The Putting Arc . Now you can feel, see and learn the Perfect Putting Stroke. Learn the 'arc type' stroke used by the vast majority of the modern day touring pros. For a 'Quick Start' and simple instructions, go to the back page. The Putting Arc works because… 1. It is based on a natural body movement which can be quickly learned and repeated. Results can be seen in several days ... thousands of repetitions are not required. 2. The clubhead travels in a perfect circle of radius R, on an inclined plane. The projection (or shadow) of this circle on the ground is a curved line called an ellipse, and this is the curve found on The Putting Arc . 3. The putter is always on plane (the sweet spot/spinal pivot plane). The intersection of this plane with the ground is a straight line, the ball/target line. (See Iron Archie - page 11) 4. The clubface is always square to the above plane. It is only square to the ball/target line at the center line on The Putting Arc . You are learning an inside to square to inside putting stroke. (See Iron Archie - page 11) 5. The lines on the top of The Putting Arc show the correct club face angle throughout the stroke, including a square initial alignment. This concept is as important as the arc itself , and it is a patented feature of The Putting Arc . 6. In this perfect putting stroke, there is only one moving part. -

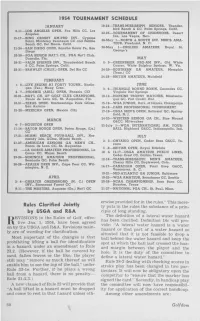

1954 TOURNAMENT SCHEDULE Rules Clarified Jointly by USGA and R&A

1954 TOURNAMENT SCHEDULE JANUARY 19-24—TRANS-MISSISSIPPI SENIORS, Thunder- bird Ranch & CC, Palm Springs, Calif. 8-11—LOS ANGELES OPEN, Fox Hills CC, Los Angeles 22-25—TOURNAMENT OF CHAMPIONS, Desert Inn, Las Vegas, Nev. 15-17—BING CROSBY AM-PRO INV., Cypress Point, Monterey Peninsula CC and Pebble 26-May 1-—NORTH & SOUTH INV. MEN'S AMA- Beach GC, Del Monte, Calif. TEUR, Pinehurst, N. C. 21-24—SAN DIEGO OPEN, Rancho Santa Fe, San 26-May 1—ENGLISH AMATEUR, Royal St. Diego George's 28-30—PGA SENIOR NAT'L CH., PGA Nat'l Club, Dunedin, Fla. MAY 28-31—PALM SPRINGS INV., Thunderbird Ranch 6- 9—GREENBRIER PRO-AM INV., Old White & CC, Palm Springs, Calif. Course, White Sulphur Springs, W. Va. 28-31—BRAWLEY (CALIF.) OPEN, Del Rio CC 24-29—SOUTHERN GA AMATEUR, Memphis (Tenn.) CC 24-29—BRITISH AMATEUR, Muirfield FEBRUARY 1- 6—LIFE BEGINS AT FORTY TOURN., Harlin- JUNE gen (Tex.) Muny Crse. 3- 6—TRIANGLE ROUND ROBIN, Cascades CC. 4- 7—PHOENIX (ARIZ.) OPEN, Phoenix CCi Virginia Hot Springs 16-21—NAT'L CH. OF GOLF CLUB CHAMPIONS, 10-12—HOPKINS TROPHY MATCHES, Mississau- Ponce de Leon GC, St. Augustine, Fla. gua GC, Port Credit, Ont. 18-21—TEXAS OPEN, Brackenridge Park GCrs®, 15-18—WGA JUNIOR, Univ. of Illinois, Champaign San Antonio 16-18—DAKS PROFESSIONAL TOURNAMENT 25-28—MEXICAN OPEN, Mexico City 17-19—USGA MEN S OPEN, Baltusrol GC, Spring- field, N. J. 24-25—WESTERN SENIOR GA CH., Blue Mound MARCH G&CC, Milwaukee 4- 7—HOUSTON OPEN 25-July 1—WGA INTERNATIONAL AM. -

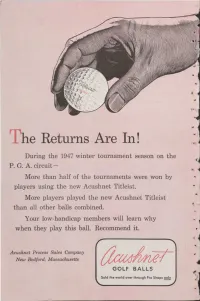

The Returns Are In!

The Returns Are In! During the 1947 winter tournament season on the P. G. A. circuit — More than half of the tournaments were won by players using the new Acushnet Titleist. More players played the new Acushnet Titleist than all other balls combined. Your low-handicap members will learn why when they play this ball. Recommend it. Acushnet Process Sales Company New Bedford, Massachusetts GOLF BALLS Sold fhe world over through Pro Shops onl' Frank Strafaci, NY Met district amateur star, has been partially crippled by recur- rence of a jungle infection he contracted when he was a GI in the Pacific. Club- houses made of used army and navy build- ings are being erected at a number of small town and muny courses. Long Beach, Calif., Meadowlark fee course is in a new men's clubhouse, lockerroom and shower- room converted from former Army bar- racks. Golf practice range business generaiiy keeping up at record figure. Goif range pros are selling pretty fair aniount of high- priced equipment. Columbus (Ga.) CC NEWS OF THE GOLF WORLD IN BRIEF B«/ IIERB GRAFFIS lets contraet for $200,000 clubhohse im- provements... American Legion opens new Smiley Quick, one of the young men who 9-hole sandgreen course at McPherson, Ks. break faithless putters says Carnoustie is ... Buddy Troyer in San Jose (Calif.) News the toughest course he played abroad. junior tournament had 30 one putt greens Windom, Minn., establishing a golf club. in 54 holes. E. W. Harbert, Chick's dad and pro at Stockton, Calif., considering new 18 hole Hamilton (O.) Elks club, says Chick was so muny course. -

2019 MASSACHUSETTS OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP June 10-12, 2019 Vesper Country Club Tyngsborough, MA

2019 MASSACHUSETTS OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP June 10-12, 2019 Vesper Country Club Tyngsborough, MA MEDIA GUIDE SOCIAL MEDIA AND ONLINE COVERAGE Media and parking credentials are not needed. However, here are a few notes to help make your experience more enjoyable. • There will be a media/tournament area set up throughout the three-day event (June 10-12) in the club house. • Complimentary lunch and beverages will be available for all media members. • Wireless Internet will be available in the media room. • Although media members are not allowed to drive carts on the course, the Mass Golf Staff will arrange for transportation on the golf course for writers and photographers. • Mass Golf will have a professional photographer – David Colt – on site on June 10 & 12. All photos will be posted online and made available for complimentary download. • Daily summaries – as well as final scores – will be posted and distributed via email to all media members upon the completion of play each day. To keep up to speed on all of the action during the day, please follow us via: • Twitter – @PlayMassGolf; #MassOpen • Facebook – @PlayMassGolf; #MassOpen • Instagram – @PlayMassGolf; #MassOpen Media Contacts: Catherine Carmignani Director of Communications and Marketing, Mass Golf 300 Arnold Palmer Blvd. | Norton, MA 02766 (774) 430-9104 | [email protected] Mark Daly Manager of Communications, Mass Golf 300 Arnold Palmer Blvd. | Norton, MA 02766 (774) 430-9073 | [email protected] CONDITIONS & REGULATIONS Entries Exemptions from Local Qualifying Entries are open to professional golfers and am- ateur golfers with an active USGA GHIN Handi- • Twenty (20) lowest scorers and ties in the 2018 cap Index not exceeding 2.4 (as determined by Massachusetts Open Championship the April 15, 2019 Handicap Revision), or who have completed their handicap certification. -

Memorial's 2010 Honoree Award

MEMORIAL’S 2010 HONOREE AWARD BACKGROUND The Memorial Tournament was founded by Jack Nicklaus in 1976 with the purpose of hosting a Tournament in recognition and honor of those individuals who have contributed to the game of golf in conspicuous honor. Since 1996 and the Memorial’s inaugural honoree, Bobby Jones, the Event has recognized many of the game’s greatest contributors. PAST HONOREES 1976 Robert T. Jones, Jr. 1993 Arnold Palmer 2005 Betsy Rawls & 1977 Walter Hagen 1994 Mickey Wright Cary Middlecoff 1978 Francis Ouimet 1995 Willie Anderson – 2006 Sir Michael Bonalack – 1979 Gene Sarazen John Ball – James Charlie Coe – William 1980 Byron Nelson Braid – Harold Lawson Little, Jr. - Henry 1981 Harry Vardon Hilton – J.H. Taylor Picard – Paul Runyan – 1982 Glenna Collett Vare 1996 Billy Casper Densmore Shute 1983 Tommy Armour 1997 Gary Player 2007 Mae Louise Suggs & 1984 Sam Snead 1998 Peter Thomson Dow H. Finsterwald, Sr. 1985 Chick Evans 1999 Ben Hogan 2008 Tony Jacklin – Ralph 1986 Roberto De Vicenzo 2000 Jack Nicklaus Guldahl – Charles Blair 1987 Tom Morris, Sr. & 2001 Payne Stewart MacDonald – Craig Wood Tom Morris, Jr. 2002 Kathy Whitworth & 2009 John Joseph Burke, Jr. & 1988 Patty Berg Bobby Locke JoAnne (Gunderson) 1989 Sir Henry Cotton 2003 Bill Campbell & Carner 1990 Jimmy Demaret Julius Boros 1991 Babe Didrikson Zaharias 2004 Lee Trevino & 1992 Joseph C. Dey, Jr Joyce Wethered SELECTION Each year the Memorial Tournament’s Captain Club membership selects the upcoming Tournament honoree. The Captains Club is comprised of a group of dignitaries from the golf industry who have helped grow and foster the professional and amateur game. -

Tiburón Golf Academy

Tiburón Golf Academy At Tiburon Golf Academy, we believe everyone can reach their fullest potential with their golf game. In order to do so, you need coaching, a process, and training. Coaching: In all sports, especially golf, the “quick fix” is never the solution. Instead, a long term approach is needed along with a trusting relationship with a coach. Here at Tiburon Golf Academy, we provide a team of coaches to help achieve your goals. Process: In order to get from where you are now to where you want to be, there is a process everyone experiences. Tiburón’s certified team first identifies the particular strengths and weaknesses through a physical screening assessment. This allows our team to tailor the best process to suit each student. Training: Upon completion of this process, your instructor will train you through all aspects of the game; short game, full swing, mental approach and on course management. These steps will enable each student to reach their full potential. Lead instructor- Tom O’Brien, PGA Born in Chelmsford, Massachusetts Tom graduated from Bentley University where he played collegiate golf. A former Head Golf Professional he valued the time he spent teaching the game. He turned that experience into full time. The last 16 years Tom has been providing exceptional golf instruction to our members, guests and local golf enthusiast. Utilizing the latest in game improvement technology Tom provides to his students all the necessary resources to improve their game. PGA / LPGA Instructor- Ellen Ceresko, LPGA Originally from Scranton, Pennsylvania Ellen is a graduate of Penn State University where she was a 4year starter for the Nittany Lions women’s golf team. -

Scoring Records for AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am

2/7/2021 PGA TOUR Statistical Inquiry Scoring Records for AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am Best 18 Hole Score: 60 Player Round Year Sung Kang 2 2016 Best Round 1 Score: 61 Player Year Charlie Wi 2012 Best Round 2 Score: 60 Player Year Sung Kang 2016 Best Round 3 Score: 62 Player Year Tom Kite 1983 David Duval 1997 Jeff Maggert 2011 Scott Brown 2015 Ted Potter, Jr. 2018 Best Round 4 Score: 63 Player Year Davis Love III 2001 Best 36 Holes: 129 Player Year Phil Mickelson 2005 Nick Taylor 2020 Best 54 Holes: 196 Player Year Phil Mickelson 2005 Dustin Johnson 2010 Paul Goydos 2010 Best 72 Holes: 265 Player Year Brandt Snedeker 2015 Holes in One Player Round Hole Year Lou Graham 2 7 1984 Hal Sutton 2 3 1985 Hubert Green 2 7 1985 John Mahaffey 3 7 1985 Rex Caldwell 1 7 1986 Brett Upper 3 5 1988 Nick Price 4 17 1988 Billy Mayfair 2 17 1989 Gil Morgan 2 3 1989 Tom Watson 2 15 1989 Carl Cooper 3 5 1990 John Joseph 3 12 1991 Rocco Mediate 2 15 1991 Greg Hickman 4 12 1992 Olin Browne 3 12 1994 Vijay Singh 2 7 1994 https://statanalysis.pgatourhq.com/inquiry/prod/index.cfm 1/3 2/7/2021 PGA TOUR Statistical Inquiry David Graham 1 7 1995 Sam Randolph 3 5 1998 Brad Fabel 2 15 2000 David Morland IV 2 5 2000 Notah Begay III 1 6 2000 John Senden 1 11 2003 Mike Heinen 2 7 2003 Robert Gamez 1 17 2003 Bill Glasson 3 5 2005 Derek Fathauer 3 15 2009 James Oh 3 15 2009 Troy Matteson 3 17 2009 Adam Scott 3 7 2010 Derek Lamely 1 14 2010 Nick O'Hern 2 12 2011 Sung Kang 3 12 2011 Boo Weekley 3 5 2012 Nick O'Hern 3 14 2012 Jim Herman 1 12 2013 Steven Alker 3 14 2015 Ryan Palmer 2 3 2016 Patrick Cantlay 1 11 2018 Anirban Lahiri 3 3 2020 Viktor Hovland 2 14 2020 Low Finish by a Winner: 63 Player Round Year Davis Love III 4 2001 High Finish by a Winner: 77 Player Round Year Ken Venturi 4 1960 Lon Hinkle 4 1979 Low Start by a Winner: 62 Player Year Phil Mickelson 2005 High Start by a Winner: 75 Player Year Jack Burke, Jr. -

1950-1959 Section History

A Chronicle of the Philadelphia Section PGA and its Members by Peter C. Trenham 1950 to 1959 Contents 1950 Ben Hogan won the U.S. Open at Merion and Henry Williams, Jr. was runner-up in the PGA Championship. 1951 Ben Hogan won the Masters and the U.S. Open before ending his eleven-year association with Hershey CC. 1952 Dave Douglas won twice on the PGA Tour while Henry Williams, Jr. and Al Besselink each won also. 1953 Al Besselink, Dave Douglas, Ed Oliver and Art Wall each won tournaments on the PGA Tour. 1954 Art Wall won at the Tournament of Champions and Dave Douglas won the Houston Open. 1955 Atlantic City hosted the PGA national meeting and the British Ryder Cup team practiced at Atlantic City CC. 1956 Mike Souchak won four times on the PGA Tour and Johnny Weitzel won a second straight Pennsylvania Open. 1957 Joe Zarhardt returned to the Section to win a Senior Open put on by Leo Fraser and the Atlantic City CC. 1958 Marty Lyons and Llanerch CC hosted the first PGA Championship contested at stroke play. 1959 Art Wall won the Masters, led the PGA Tour in money winnings and was named PGA Player of the Year. 1950 In early January Robert “Skee” Riegel announced that he was turning pro. Riegel who had grown up in east- ern Pennsylvania had won the U.S. Amateur in 1947 while living in California. He was now playing out of Tulsa, Oklahoma. At that time the PGA rules prohibited him from accepting any money on the PGA Tour for six months. -

PGA of America Awards

THE 2006 PGA MEDIA GUIDE – 411 PGA of America Awards ¢ PGA Player of the Year The PGA Player of the Year Award is given to the top PGA Tour player based on his tournament wins, official money standing and scoring average. The point system for selecting the PGA Player of the Year was amended in 1982 and is as follows: 30 points for winning the PGA Championship, U.S. Open, British Open or Masters; 20 points for winning The Players Championship; and 10 points for winning all other designated PGA Tour events. In addition, there is a 50-point bonus for winning two majors, 75-point bonus for winning three, 100-point bonus for winning four. For top 10 finishes on the PGA Tour’s official money and scoring average lists for the year, the point value is: first, 20 points, then 18, 16, 14, 12, 10, 8, 6, 4, 2. Any incomplete rounds in the scoring average list will result in a .10 penalty per incomplete round. 1948 Ben Hogan 1960 Arnold Palmer 1972 Jack Nicklaus 1984 Tom Watson Tiger Woods 1949 Sam Snead 1961 Jerry Barber 1973 Jack Nicklaus 1985 Lanny Wadkins 1950 Ben Hogan 1962 Arnold Palmer 1974 Johnny Miller 1986 Bob Tway 1996 Tom Lehman 1951 Ben Hogan 1963 Julius Boros 1975 Jack Nicklaus 1987 Paul Azinger 1997 Tiger Woods 1952 Julius Boros 1964 Ken Venturi 1976 Jack Nicklaus 1988 Curtis Strange 1998 Mark O’Meara 1953 Ben Hogan 1965 Dave Marr 1977 Tom Watson 1989 Tom Kite 1999 Tiger Woods 1954 Ed Furgol 1966 Billy Casper 1978 Tom Watson 1990 Nick Faldo 2000 Tiger Woods 1955 Doug Ford 1967 Jack Nicklaus 1979 Tom Watson 1991 Corey Pavin 2001 Tiger Woods 1956 Jack Burke Jr. -

PPCO Twist System

Welcome to the April issue of digital Golf Range Magazine! Inside the April issue, you will find the following features: • Business of Teaching: Marketing to the Serious Golfer – The high- income, high-frequency golfer who says that score is important to enjoyment of the game is—or could be—a cornerstone of your instruction program. • Clubfitting: Making Demo Day More about the Pro – Major golf gear brands deliver excitement during Demo Day events, but increasingly they’re turning the spotlight back onto on-site professionals. • Resort Range Profile: Four Seasons Dallas – The glory days of corporate golf schools ended abruptly several years ago—except at Four Seasons in Dallas. In case you forgot the formula, here’s how they spell success. • Range Marketing: Catching Golfers in Your Website – Ranges like Man O’War Golf Learning Center take a workhorse approach to their websites—making sure that customer data, engagement and revenue are top priorities. Keep it fun and thanks for supporting the GRAA. Best Regards, Rick Summers, CEO GRAA [email protected] VIDEO: SUSAN ROLL • GOLF RANGE NEWS • CREATE A CUSTOMER SURVEY Golf RangeVolume 20, No. 4 MAGAZINE April 2012 Teaching the Serious Player Stats Reveal What That Golfer Wants Now Also in this issue: • Websites That Work • Get More out of Demo Day • GRAA Awards: How to Enter • Corporate Golf Hideaway TEEINGOFF Page 22 A Demo Day Facelift WWW.GOLFRANGE.ORG APRIL 2012 | GOLF RANGE MAGAZINE | 3 TEEINGOFF Page 26 Where Corporate Golf Lives On WWW.GOLFRANGE.ORG APRIL 2012 | GOLF RANGE MAGAZINE | 5 CONTENTS Golf Range MAGAZINE Volume 20, Number 4 April 2012 Features 20 Business of Teaching: Marketing to the Serious Golfer The high-income, high-frequency golfer who says that score is important to enjoyment of the game is—or could be—a cornerstone of your instruction program By David Gould 22 22 Clubfitting: Making Demo Day More about the Pro Major golf gear brands deliver excitement during Demo Day events, but increasingly they’re turning the spotlight back onto on-site professionals. -

Courage Award for Gene Littler” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 6, folder “3/26/76 - Courage Award for Gene Littler” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Date Issued 3/19/ 76 Bys. Porter Revised---- FACT SHEET Mrs. Ford's Office Event ______P_r_e_s_e_n_t_l_9_7_6_c_o_u_r_a...:.g~e_A_w_a_r_d_f_o_r_c_a_n_c_e_r_t_o __ G_e_n_e_L_i_t_t_l_e_r ________ _ Group _____~Am_:_::e_r~i~c~a~n.::_C~a~n~c~e~r __ s_o_c_i_e_t;y ____ ~-------------------- DATE/TIME __=F=r=i=d=a~yL,-=M=a~r~ch=-~2~6~,...:.l=.9~7~6=-<--,...:.3~·~·0~0:__.iP~·=m~.=------------------- Contact _____:Mr:.:=..:.· _:::I.::.r..:.v--=.R::::im=e==r=--------------------- Phone (212) 371-2900 Number of guests: Total 11 Women X Men x Children ------ ·------ ----- Place Diplomatic Reception Room Principals involved Mr==s..:.·-=.F-=o-=r:..::d=--------------------------------- Participation by Principal Present Award; Photos (Receiving line)--------------- Remarks required No; background material only ~ Background The Courage Award is presented annually by the American Cancer Society to someone of distinction who has had cancer and who has courageously faced the disease and who is an example to others.