DISCUSSION Office of the Superintendent of Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

These Locations Are Available for Use Now | Estas Ubicaciones Ya Están Desponibles These Locations Will Be Available for Use By

Montgomery County - Ballot Drop Off Locations for the 2020 Presidential General Election | Condado de Montgomery – Ubicaciones de entrega de papeletas para las elecciones generals presidenciales de 2020 These locations are available for use now | Estas ubicaciones ya están desponibles Montgomery County Board of Elections 18753 North Frederick Avenue Gaithersburg, MD 20879 (Drive-up Box) City of Rockville 111 Maryland Avenue Rockville, MD 20850 (City Hall Parking Lot | Estacionamiento de la Municipalidad) (Drive-up Box) Executive Office Building 101 Monroe Street Rockville, MD 20850 These locations will be available for use by September 28th - 30th | Estas ubicaciones estarán disponibles para su uso entre el 28 al 30 de septiembre Activity Center at Bohrer Park 506 South Frederick Avenue Gaithersburg, MD 20877 Clarksburg High School 22500 Wims Road Clarksburg, MD 20871 Col. Zadok Magruder High School 5939 Muncaster Mill Road Rockville, MD 20855 Damascus Community Recreation Center 25520 Oak Drive Damascus, MD 20872 Germantown Community Recreation Center 18905 Kingsview Road Germantown, MD 20874 Jane E. Lawton Community Recreation Center 4301 Willow Lane Chevy Chase, MD 20815 Marilyn J. Praisner Community Recreation Center 14906 Old Columbia Pike Burtonsville, MD 20866 Mid-County Community Recreation Center 2004 Queensguard Road Silver Spring, MD 20906 Montgomery Blair High School 51 University Boulevard East Silver Spring, MD 20901 Montgomery Co. Conference Center Marriott Bethesda North 5967 Executive Boulevard North Bethesda, MD 20852 -

ARE YOU READY to VOTE in PERSON on ELECTION DAY? Montgomery County Will Open 39 Election Day Vote Centers on November 3, 2020, from 7 A.M

ARE YOU READY TO VOTE IN PERSON ON ELECTION DAY? Montgomery County will open 39 Election Day Vote Centers on November 3, 2020, from 7 a.m. – 8 p.m. On Election Day you may vote at any one of Montgomery County’s 39 Election Day Vote Centers. Most polling places will be closed due to the pandemic. Instead, you may vote at any vote center. Same-day registration is available with proof of residency. Due to the pandemic, we will limit the number of people inside vote centers at one time and distance voting booths at least six feet apart. This will result in longer lines and wait times. For the closest Election Day vote center and wait-times, text VC plus your ZIP code to 77788 (Example: VC 20879). Maryland's voting system offers features for accessibility. Please ask the Election Judge about your options. Before you are given a ballot, an Election Judge will tell you, "You have two ways to mark your ballot - either by hand or with the electronic device. Which do you prefer?" You will choose how to mark your ballot. If you requested a ballot by mail, please vote that ballot. There will be a drop box at every in- person voting center, so you can skip the line and drop off your ballot. For additional drop boxes near you, text BOX plus your ZIP code to 77788 (Example: BOX 20879). You may not “trade in” your by-mail ballot at a vote center. If you requested a ballot by mail and try to vote in person, you will need to apply for a provisional ballot, which adds time to your voting experience. -

2011-12 NISCA/Speedo Swimming and Diving All America All-America Certificates Will Be Mailed Directly to Athletes That Achieved "Top 100" Performances in All Events

NISCA All-America Swimming and Diving 2011 - 2012 Page 1 of 1 2011-12 NISCA/Speedo Swimming and Diving All America All-America Certificates will be mailed directly to athletes that achieved "Top 100" performances in all events. Please check events, times and spelling for accuracy. Boys Swimming contact: [email protected] Girls Swimming contact: [email protected] Boys and Girls Diving contact: [email protected] National Interscholastic Swimming Coaches Association 2010-2011 All-America Swimmers and Divers 200 Med Rel 200 Free 200 Ind Med 50 Free Dive 100 Fly Boys Events in 100 Free 400 Fr Yards 500 Free 200 Fr Rel 100 Back 100 Breast Re1 Girls Events in 200 Med Rel 200 Free 200 Ind Med 50 Free Dive 100 Fly Yards 100 Free 500 Free 200 Fr Rel 100 Back 100 Breast 400 Fr Rel All-America Final Standings by State and Gender Statistics All-America Applications by Event and Gender 2012-13 Yard Time Standards 2012-13 Standard Seven Years of Time Standards 2012-13 Meter Time Determinations Standards Guidelines Back to IHSSCA Back to NISCA http://www.inswim.net/allam12.html 6/27/2012 2011-2012 NISCA Boys All-America 200 Yard Medley Relay Page 1 of 7 2011-12 NISCA/Speedo Boys High School Swimming All-America 200 Yard Medley Relay - Automatic AA 1:35.11 NATIONAL RECORD: 1:31.10 - Mercersburg Academy (Zasha Robles, Mike Kidd, Brian Craft and Greg Gipson) Mercersburg, PA - February 21, 1992 Place Time Swimmers (Yrs) School City State Preston Jenkins (12), Matteus Martini 1 1:30.17 (12), Joseph Schooling (10), Ryan The Bolles School -

MLS DEIS Appendix E

APPENDIX E COMMUNITY EFFECTS ASSESSMENT AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE ANALYSIS May 2020 COMMUNITY EFFECTS ASSESSMENT AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Overview ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Study Corridors ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Study Purpose and Need ............................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Alternatives Evaluated .................................................................................................................. 4 2 METHODOLOGY..........................................................................................................................9 2.1 CEA Analysis Area .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Data Collection ............................................................................................................................ 10 2.3 Analysis of Environmental Consequences .................................................................................. 15 3 EXISTING CONDITIONS AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES ................................................ 16 3.1 Land -

Team Scores Place School Points 1 the Holton-Arms School the Holton-Arms School 451

RMSC - MCRD HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - 10:44 AM 2/10/2019 Page 1 2019 WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN INTERSCHOLASTIC SWIMMING AND DIVING CHAMPIONSHIPS Team Rankings - Through Event 24 Girls - Team Scores Place School Points 1 The Holton-Arms School The Holton-Arms School 451 . 50 2 Bethesda-Chevy Chase HS Bethesda-Chevy Chase HS 282 3 Sherwood Warriors Sherwood Warriors 274 . 50 4 Stone Ridge Stone Ridge 256 5 Our Lady of Good Counsel Our Lady of Good Counsel 217 . 50 6 Walter Johnson High School Walter Johnson High School 193 . 50 7 Quince Orchard High School Quince Orchard High School 189 . 50 8 Walt Whitman Swim & Dive Team Walt Whitman Swim & Dive Team 189 9 Churchill High School Churchill High School 169 10 Montgomery Blair High School Montgomery Blair High School 120 11 Georgetown Visitation Georgetown Visitation 115 12 Magruder High School Magruder High School 97 13 Potomac School Swim Team Potomac School Swim Team 95 14 Poolesville High School Poolesville High School 87 15 St. John's College High School St. John's College High School 82 16 Wootton High School Wootton High School 77 16 Damascus High School Damascus High School 77 18 Einstein High School Einstein High School 70 19 Richard Montgomery High School Richard Montgomery High School 63 20 Academy of the Holy Cross Academy of the Holy Cross 51 21 Northwest High School Northwest High School 49 22 Washington Christian Acadamy Washington Christian Acadamy 45 23 St. Vincent Pallotti HS St. Vincent Pallotti HS 34 24 National Cathedral School National Cathedral School 33 25 Clarksburg High School Clarksburg High School 31 25 Maret School Maret School 31 27 Springbrook High School Springbrook High School 22 28 St. -

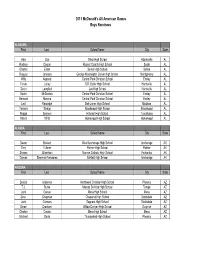

2011 Combined Nominee List

2011 McDonald's All American Games Boys Nominees ALABAMA First Last School Name City State Alex Carr Minor High School Adamsville AL Rodney Cooper Russell County High School Seale AL Charles Eaton Selma High School Selma AL Roquez Johnson George Washington Carver High School Montgomery AL Willy Kouassi Central Park Christian School Ensley AL Trevor Lacey S.R. Butler High School Huntsville AL Devin Langford Lee High School Huntsville AL Kevin McDaniels Central Park Christian School Ensley AL Bernard Morena Central Park Christian School Ensley AL Levi Randolph Bob Jones High School Madison AL Tavares Sledge Brookwood High School Brookwood AL Reggie Spencer Hillcrest High School Tuscaloosa AL Marvin Whitt Homewood High School Homewood AL ALASKA First Last School Name City State Devon Bookert West Anchorage High School Anchorage AK Trey Fullmer Palmer High School Palmer AK Shayne Gilbertson Monroe Catholic High School Fairbanks AK Damon Sherman-Newsome Bartlett High School Anchorage AK ARIZONA First Last School Name City State Dakota Anderson Northwest Christian High School Phoenix AZ T.J. Burke Marcos De Niza High School Tempe AZ Jahii Carson Mesa High School Mesa AZ Zeke Chapman Chaparral High School Scottsdale AZ Jack Connors Saguaro High School Scottsdale AZ Deion Crockom Willow Canyon High School Surprise AZ Charles Croxen Mesa High School Mesa AZ Michael Davis Thunderbird High School Phoenix AZ 2011 McDonald's All American Games Boys Nominees Conor Farquharson Shadow Mountain High School Phoenix AZ Cameron Forte McClintock High School -

Election Day Vote Centers Each Vote Center Will Be Open November 3, 2020 from 7 Am to 8 Pm

2020 General Election Election Day Vote Centers Each vote center will be open November 3, 2020 from 7 am to 8 pm. Voters in line at 8 pm will be able to vote. County Location Address City State Zip Allegany Allegany County Office Complex, Room 100 701 Kelly Road Cumberland MD 21502 Allegany Allegany High School 900 Seton Drive Cumberland MD 21502 Allegany Flintstone Volunteer Fire Dept 21701 Flintstone Drive NE Flintstone MD 21530 Allegany Fort Hill High School 500 Greenway Avenue Cumberland MD 21502 Allegany Mountain Ridge High School 100 Dr. Nancy S Grasmick Lane Frostburg MD 21532 Allegany Westmar Middle School 16915 Lower Georges Creek Road SW Lonaconing MD 21539 Anne Arundel Annapolis High School 2700 Riva Road Annapolis MD 21401 Anne Arundel Arnold Elementary School 95 E Joyce Lane Arnold MD 21012 Anne Arundel Arundel High School 1001 Annapolis Road Gambrills MD 21054 Anne Arundel Bates Middle School 701 Chase Street Annapolis MD 21401 Anne Arundel Broadneck High School 1265 Green Holly Drive Annapolis MD 21409 Anne Arundel Brock Bridge Elementary School 405 Brock Bridge Road Laurel MD 20724 Anne Arundel Brooklyn Park Middle School 200 Hammonds Lane Baltimore MD 21225 Anne Arundel Chesapeake High School 4798 Mountain Road Pasadena MD 21122 Anne Arundel Chesapeake Science Point Charter School 7321 Parkway Drive South Hanover MD 21076 Anne Arundel Corkran Middle School 7600 Quarterfield Road Glen Burnie MD 21061 Anne Arundel Crofton Elementary School 1405 Duke of Kent Drive Crofton MD 21114 Anne Arundel Crofton Middle School 2301 -

ACTION Office of the Superintendent of Schools MONTGOMERY

ACTION Office of the Superintendent of Schools MONTGOMERY COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Rockville, Maryland July 15, 2021 MEMORANDUM To: Members of the Board of Education From: Monifa B. McKnight, Interim Superintendent of Schools Subject: Retirement of Montgomery County Public Schools Personnel WHEREAS, The persons on the attached list are retiring or have retired from Montgomery County Public Schools; and WHEREAS, Each person, through outstanding performance of duties and dedication to the education of our youth, has made a significant contribution to the school system, which is worthy of special commendation; now therefore be it Resolved, That the members of the Board of Education express their sincere appreciation to each person for faithful service to the school system and to the children of the county, and also extend to each one best wishes for the future; and be it further Resolved, That a copy of this resolution is published on the Employee and Retiree Service Center web page and available to each retiree. MBM:DKM:KT:sy Attachment Name and Latest Assignment Montgomery County Years of Service Mrs. Linda M. Abadia Bus Route Supervisor Department of Transportation, effective, 6/1/2021 15.2 Ms. Joy A. Abiodun Teacher Newport Mill Middle School, effective, 7/1/2021 17.7 Mrs. Laura D. Acuna Paraeducator, Special Education Damascus High School, effective, 2/1/2021 30.0 Mr. Joseph Addo Building Service Assistant Manager IV Shift 2 Paint Branch High School, effective, 2/1/2021 27.4 Mr. Ohannes A. Aghguiguian Bus Operator I Department of Transportation, effective, 7/1/2021 15.8 Mr. Luis G. -

Maryland Players Selected in Major League Baseball Free-Agent Drafts

Maryland Players selected in Major League Baseball Free-Agent Drafts Compiled by the Maryland State Association of Baseball Coaches Updated 16 February 2021 Table of Contents History .............................................................................. 2 MLB Draft Selections by Year ......................................... 3 Maryland First Round MLB Draft Selections ................. 27 Maryland Draft Selections Making the Majors ............... 28 MLB Draft Selections by Maryland Player .................... 31 MLB Draft Selections by Maryland High School ........... 53 MLB Draft Selections by Maryland College .................. 77 1 History Major League Baseball’s annual First-Year Player Draft began in June, 1965. The purpose of the draft is to assign amateur baseball players to major league teams. The draft order is determined based on the previous season's standings, with the team possessing the worst record receiving the first pick. Eligible amateur players include graduated high school players who have not attended college, any junior or community college players, and players at four-year colleges and universities three years after first enrolling or after their 21st birthdays (whichever occurs first). From 1966-1986, a January draft was held in addition to the June draft targeting high school players who graduated in the winter, junior college players, and players who had dropped out of four-year colleges and universities. To date, there have been 1,170 Maryland players selected in the First-Year Player Drafts either from a Maryland High School (337), Maryland College (458), Non-Maryland College (357), or a Maryland amateur baseball club (18). The most Maryland selections in a year was in 1970 (38) followed by 1984 (37) and 1983 (36). The first Maryland selection was Jim Spencer from Andover High School with the 11th overall selection in the inaugural 1965 June draft. -

2015 WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN INTERSCHOLASTIC, Sanction #: PVO-15-207 SWIMMING and DIVING CHAMPIONSHIPS Team Rankings

RMSC - MCRD HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 5.0 - 12:43 PM 2/8/2015 Page 1 2015 WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN INTERSCHOLASTIC, Sanction #: PVO-15-207 SWIMMING AND DIVING CHAMPIONSHIPS Team Rankings - Through Event 24 Girls - Team Scores Place School Points 1 Churchill High School Churchill High School 412 .50 2 The Holton-Arms School The Holton-Arms School 245 3 Montgomery Blair Montgomery Blair 236 .50 4 Sherwood High School Sherwood High School 221 5 Walter Johnson High School Walter Johnson High School 216 6 Northwest High School Northwest High School 209 7 Stone Ridge Stone Ridge 181 .50 8 Richard Montgomery High School Richard Montgomery High School 172 9 Madeira Varsity Swim Team Madeira Varsity Swim Team 154 10 Poolesville High School Poolesville High School 152 11 Wootton High School Wootton High School 148 12 Bethesda-Chevy Chase HS Bethesda-Chevy Chase HS 131 12 Our Lady of Good Counsel Our Lady of Good Counsel 131 14 St. John's College High School St. John's College High School 116 .50 15 Walt Whitman Walt Whitman 103 16 Academy of the Holy Cross Academy of the Holy Cross 84 17 Sidwell Friends School Sidwell Friends School 83 18 Quince Orchard High School Quince Orchard High School 58 19 Blake High School Blake High School 56 20 Potomac School Swim Team Potomac School Swim Team 47 21 National Cathedral/W National Cathedral/W 38 22 Springbrook High School Springbrook High School 31 22 Albert Einsten H. S. Swim Albert Einsten H. S. Swim 31 24 Gaithersburg High School Gaithersburg High School 27 25 Holy Child Holy Child 24 26 Damascus High School -

Scholar Athletes

2018-2019 Potomac Valley Scholar Athletes First Name Last Name High School Graduation Year USA Swimming Club Sarah Boyle Westfield High School 2019 Machine Aquatics Ryan Bracewell Chantilly 2019 Potomac Marlins Grace Burgett Walter Johnson High School 2019 Rockville Montgomery Swim Club Alexus Kate Chua Oakton 2019 Machine Aquatics Sean Conway Loudoun Valley High School 2019 Nation's Capital Diego Cruzado The Potomac School 2019 Machine Aquatics Alexa Cuomo Centreville High School 2019 Mason Makos Kyrsten Davis South County High School 2019 Nation's Capital Gilbert Diaz Homeschool high school 2019 Occoquan Swimming Timothy Ellett Walter Johnson High School 2019 Rockville Montgomery Swim Club Rita Frie Woodgrove High School 2019 Snow Swimming Elias Griffin West Springfield 2019 Mason Makos Gabriel Laracuente Our Lady of Good Counsel High School 2019 Nation's Capital William Lewis Walt Whitman High School 2019 Nation's Capital Katie Mack Homeschool High School 2019 Nation's Capital Megan Mastropaolo Patriot 2019 Nation's Capital Olivia McCarthy Osbourn Park High School 2019 Nation's Capital Jackson McCummings Riverside High School 2019 Nation's Capital Elise Mozeleski Chantilly 2019 Machine Aquatics Andrew Munson Our Lady of Good Counsel High School 2019 Rockville Montgomery Swim Club Alaina Park Lake Braddock Secondary 2019 Potomac Marlins Michael Penafiel St. John's College High School 2019 Rockville Montgomery Swim Club D. Harrison Rehr Yorktown High School 2019 York Swim Club Sean Reilly Robinson 2019 Nation's Capital Sophie Reilly Walt Whitman High School 2019 Nation's Capital Allison Ritter Mount Hebron High School 2019 Maryland Suburban Swim Club Sophia Ryan Sherwood 2019 Rockville Montgomery Swim Club Olivia Santee Patriot High School 2019 Nation's Capital Andrei Schwartz Saint Albans School 2019 Rockville Montgomery Swim Club Mary (Teddy) Segmuller Foxcroft 2019 Occoquan Swimming Connor Smith The Potomac School 2019 Machine Aquatics Sunil Surprenant James H. -

Of 217 11:45:20AM Club Information Report CUS9503 09/01/2021

Run Date: 09/22/2021 Key Club CUS9503 Run Time: 11:53:54AM Club Information Report Page 1 of 217 Class: KCCLUB Districts from H01 to H99 Admin. Start Date 10/01/2020 to 09/30/2021 Club Name State Club ID Sts Club Advisor Pd Date Mbr Cnt Pd Amount Kiwanis Sponsor Club ID Div H01 - Alabama Abbeville Christian Academy AL H90124 Debbie Barnes 12/05/2020 25 175.00 Abbeville K04677 K0106 Abbeville High School AL H87789 Valerie Roberson 07/06/2021 9 63.00 Abbeville K04677 K0106 Addison High School AL H92277 Mrs Brook Beam 02/10/2021 19 133.00 Cullman K00468 K0102 Alabama Christian Academy AL H89446 I Page Clayton 0 Montgomery K00174 K0108 Alabama School Of Mathematics And S AL H88720 Derek V Barry 11/20/2020 31 217.00 Azalea City, Mobile K10440 K0107 Alexandria High School AL H89049 Teralyn Foster 02/12/2021 29 203.00 Anniston K00277 K0104 American Christian Academy AL H94160 I 0 Andalusia High School AL H80592 I Daniel Bulger 0 Andalusia K03084 K0106 Anniston High School AL H92151 I 0 Ashford High School AL H83507 I LuAnn Whitten 0 Dothan K00306 K0106 Auburn High School AL H81645 Audra Welch 02/01/2021 54 378.00 Auburn K01720 K0105 Austin High School AL H90675 Dawn Wimberley 01/26/2021 36 252.00 Decatur K00230 K0101 B.B. Comer Memorial School AL H89769 Gavin McCartney 02/18/2021 18 126.00 Sylacauga K04178 K0104 Baker High School AL H86128 0 Mobile K00139 K0107 Baldwin County High School AL H80951 Sandra Stacey 11/02/2020 34 238.00 Bayside Academy AL H92084 Rochelle Tripp 11/01/2020 67 469.00 Daphne-Spanish Fort K13360 K0107 Beauregard High School AL H91788 I C Scott Fleming 0 Opelika K00241 K0105 Benjamin Russell High School AL H80742 I Mandi Burr 0 Alexander City K02901 K0104 Bessemer Academy AL H90624 I 0 Bob Jones High School AL H86997 I Shari Windsor 0 Booker T.