The Great Gatsby: from Novel Into Opera Laura Ann Storm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

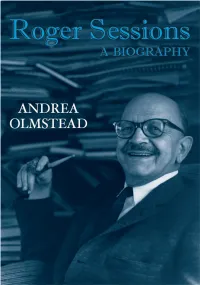

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

Now Again New Music Music by Bernard Rands Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor with Guest Janice Felty, Mezzo-Soprano Now Again

Network for Now Again New Music Music by Bernard Rands Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor with guest Janice Felty, mezzo-soprano Now Again Music by Bernard Rands Network for New Music Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor www.albanyrecords.com TROY1194 albany records u.s. 915 broadway, albany, ny 12207 with guest Janice Felty, tel: 518.436.8814 fax: 518.436.0643 albany records u.k. box 137, kendal, cumbria la8 0xd mezzo-soprano tel: 01539 824008 © 2010 albany records made in the usa ddd waRning: cOpyrighT subsisTs in all Recordings issued undeR This label. The story is probably apocryphal, but it was said his students at Harvard had offered a prize to anyone finding a wantonly decorative note or gesture in any of Bernard Rands’ music. Small ensembles, single instrumental lines and tones convey implicitly Rands’ own inner, but arching, songfulness. In his recent songs, Rands has probed the essence of letter sounds, silence and stress in a daring voyage toward the center of a new world of dramatic, poetic expression. When he wrote “now again”—fragments from Sappho, sung here by Janice Felty, he was also A conversation between composer David Felder and filmmaker Elliot Caplan about Shamayim. refreshing his long association with the virtuosic instrumentalists of Network for New Music, the Philadelphia ensemble marking its 25th year in this recording. These songs were performed in a 2009 concert for Rands’ 75th birthday — and offer no hope for winning the prize for discovering extraneous notes or gestures. They offer, however, an intimate revelation of the composer’s grasp of color and shade, his joy in the pulsing heart, his thrill at the glimpse of what’s just ahead. -

An Analysis and Performance Considerations for John

AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN (Under the Direction of D. RAY MCCLELLAN) ABSTRACT John Harbison is an award-winning and prolific American composer. He has written for almost every conceivable genre of concert performance with styles ranging from jazz to pre-classical forms. The focus of this study, his Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, was premiered in 1985 as a product of a Consortium Commission awarded by the National Endowment of the Arts. The initial discussions for the composition were with oboist Sara Bloom and clarinetist David Shifrin. Harbison’s Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings allows the clarinet to finally be introduced to the concerto grosso texture of the Baroque period, for which it was born too late. This document includes biographical information on John Harbison including his life and career, compositional style, and compositional output. It also contains a brief history of the Baroque concerto grosso and how it relates to the Harbison concerto. There is a detailed set-class analysis of each movement and information on performance considerations. The two performers as well as the composer were interviewed to discuss the commission, premieres, and theoretical/performance considerations for the concerto. INDEX WORDS: John Harbison, Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, clarinet concerto, oboe concerto, Baroque concerto grosso, analysis and performance AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN B.M., Tennessee Technological University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Katherine Belvin All Rights Reserved AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN Major Professor: D. -

The New York Virtuoso Singers

Merkin Concert Hall at Kaufman Center Presents The New York Virtuoso Singers Announcing the 25th Anniversary Season Merkin Concert Hall Performances – 2012-13 Concerts Feature 25 Commissioned Works by Major American Composers The New York Virtuoso Singers, Harold Rosenbaum, Conductor and Artistic Director, have announced Merkin Concert Hall dates for their 2012-13 concert season. This will be the group’s 25th anniversary season. To celebrate, they will present concerts on October 21, 2012 and March 3, 2013 at Kaufman Center’s Merkin Concert Hall, 129 West 67th St. (btw Broadway and Amsterdam) in Manhattan, marking their return to the hall where they presented their first concert in 1988. These concerts will feature world premieres of commissioned new works from 25 major American composers – Mark Adamo, Bruce Adolphe, William Bolcom, John Corigliano, Richard Danielpour, Roger Davidson, David Del Tredici, David Felder, John Harbison, Stephen Hartke, Jennifer Higdon, Aaron Jay Kernis, David Lang, Fred Lerdahl, Thea Musgrave, Shulamit Ran, Joseph Schwantner, Steven Stucky, Augusta Read Thomas, Joan Tower, George Tsontakis, Richard Wernick, Chen Yi, Yehudi Wyner and Ellen Taaffe Zwilich. Both concerts will also feature The Canticum Novum Youth Choir, Edie Rosenbaum, Director. The Merkin Concert Hall dates are: Sunday, October 21, 2012 at 3 pm - 25th Anniversary Celebration Pre-concert discussion with the composers at 2:15 pm World premieres by Jennifer Higdon, George Tsontakis, John Corigliano, David Del Tredici, Shulamit Ran, John Harbison, Steven Stucky, Stephen Hartke, Fred Lerdahl, Chen Yi, Bruce Adolphe and Yehudi Wyner – with Brent Funderburk, piano. More about this concert at http://kaufman-center.org/mch/event/the-new-york-virtuoso- singers. -

The Great Gatsby – Opening of Chapter 3

The Great Gatsby – Opening of Chapter 3 The Great Gatsby is a novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, set in 1920s America. It is narrated by Nick Carraway, a man in his late 20s, who has moved to Long Island to commute to his job in New York City trading bonds. He moves next door to Jay Gatsby, a man who has earned a reputation for an extravagant lifestyle but is a somewhat enigmatic figure. At this point in the novel, Nick hasn’t even met Gatsby, despite hearing a lot about him. There was music from my neighbor’s house through the summer nights. In his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars. At high tide in the afternoon I watched his guests diving from the tower of his raft, or taking the sun on the hot sand of his beach while his two motor-boats slit the waters of the Sound, drawing aquaplanes over cataracts of foam. On week-ends his Rolls- Royce became an omnibus, bearing parties to and from the city between nine in the morning and long past midnight, while his station wagon scampered like a brisk yellow bug to meet all trains. And on Mondays eight servants, including an extra gardener, toiled all day with mops and scrubbing-brushes and hammers and garden-shears, repairing the ravages of the night before. Every Friday five crates of oranges and lemons arrived from a fruiterer in New York — every Monday these same oranges and lemons left his back door in a pyramid of pulpless halves. -

Program Notes and Translations for a Graduate Voice Recital Sara Arias Ruiz Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 6-4-2004 Program notes and translations for a graduate voice recital Sara Arias Ruiz Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14032343 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Arias Ruiz, Sara, "Program notes and translations for a graduate voice recital" (2004). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1060. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1060 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida PROGRAM NOTES AND TRANSLATIONS FOR A GRADUATE VOICE RECITAL A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by Sara Arias Ruiz 2004 To: Dean R. Bruce Dunlap College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Sara Arias Ruiz, and entitled Program Notes and Translations for a Graduate Voice Recital, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Linda M. Considine Nancy Rao Robert B. Dundas, Major Professor Date of Defense: June 4, 2004 The thesis of Sara Arias Ruiz is approved. Dean R. Bre Dunlap College of Arts and Sciences ean Douo rtzok University Graduate School Florida International University, 2004 ii ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS PROGRAM NOTES AND TRANSLATIONS FOR A GRADUATE VOICE RECITAL by Sara Arias Ruiz Florida International University, 2004 Miami, Florida Professor Robert B. -

2005 Distinguished Faculty, John Hall

The Complete Recitalist June 9-23 n Singing On Stage June 18-July 3 n Distinguished faculty John Harbison, Jake Heggie, Martin Katz, and others 2005 Distinguished Faculty, John Hall Welcome to Songfest 2005! “Search and see whether there is not some place where you may invest your humanity.” – Albert Schweitzer 1996 Young Artist program with co-founder John Hall. Songfest 2005 is supported, in part, by grants from the Aaron Copland Fund for Music and the Virgil Thomson Foundation. Songfest photography courtesy of Luisa Gulley. Songfest is a 501(c)3 corporation. All donations are 100% tax-deductible to the full extent permitted by law. Dear Friends, It is a great honor and joy for me to present Songfest 2005 at Pepperdine University once again this summer. In our third year of residence at this beautiful ocean-side Malibu campus, Songfest has grown to encompass an ever-widening circle of inspiration and achievement. Always focusing on the special relationship between singer and pianist, we have moved on from our unique emphasis on recognized masterworks of art song to exploring the varied and rich American Song. We are once again privileged to have John Harbison with us this summer. He has generously donated a commission to Songfest – Vocalism – to be premiered on the June 19 concert. Our singers and pianists will be previewing his new song cycle on poems by Milosz. Each time I read these beautiful poems, I am reminded why we love this music and how our lives are enriched. What an honor and unique opportunity this is for Songfest. -

Notes on the Oedipus Works

Notes on the Oedipus Works Matthew Aucoin The Orphic Moment a dramatic cantata for high voice (countertenor or mezzo-soprano), solo violin, and chamber ensemble (15 players) The story of Orpheus is music’s founding myth, its primal self-justification and self-glorification. On Orpheus’s wedding day, his wife, Eurydice, is fatally bitten by a poisonous snake. Orpheus audaciously storms the gates of Hell to plead his case, in song, to Hades and his infernal gang. The guardians of death melt at his music’s touch. They grant Eurydice a second chance at life: she may follow Orpheus back to Earth, on the one condition that he not turn to look at her until they’re above ground. Orpheus can’t resist his urge to glance back; he turns, and Eurydice vanishes. The Orpheus myth is typically understood as a tragedy of human impatience: even when a loved one’s life is at stake, the best, most heroic intentions are helpless to resist a sudden instinctive impulse. But that’s not my understanding of the story. Orpheus, after all, is the ultimate aesthete: he’s the world’s greatest singer, and he knows that heartbreak and loss are music’s favorite subjects. In most operas based on the Orpheus story – and there are many – the action typically runs as follows: Orpheus loses Eurydice; he laments her loss gorgeously and extravagantly; he descends to the underworld; he gorgeously and extravagantly begs to get Eurydice back; he is granted her again and promptly loses her again; he laments even more gorgeously and extravagantly than before. -

"A Fragment of Lost Words": Narrative Ellipses in the Great Gatsby. Matthew J

"A Fragment of Lost Words": Narrative Ellipses in The Great Gatsby. Matthew J. Bolton As a great short novel. The Great Gatsby gathers force and power not only from what it says, but also from what it chooses not to say. Nick Carraway, Fitzgerald's enigmatic narrator, relates Jay Gatsby's story in a manner that is at once concise and elliptical. These two quali- ties are not at odds with each other; in fact, the more concise one is, the more one must leave out. Such narrative elisions—the places in the text where Nick omits important information or jumps over some event in Gatsby's life or his own—might draw the reader's attention to the process of selection that is at work in the novel as a whole. Every narra- tive has elisions. Wolfgang Iser terms these moments "gaps," and ar- gues that differences in interpretations arise from readers filling the narrative's gaps in different ways: One text is potentially capable of several different realizations, and no reading can ever exhaust the flill potential, for each individual reader will fill in the gaps in his own way, thereby excluding the various other possi- bilities; as he reads, he will make his own decision as to how the gap is to be filled. (280) Such gaps are of particular importance in The Great Gatsby, for the novel's brevity (180 pages in the Scribner edition) is predicated on its narrator's selectivity, on his readiness to leave some things unsaid. Nick has powers of concentration and elimination that one might more readily associate with the lyric poet than with the novelist. -

The Art of Fugue

Emmanuel Music’s Bach Signature Season: The Art of Fugue Emmanuel Music’s 2007-08 Bach Signature Season switches into an intimate chamber mode on Wednesday evening, October 10. But there will also be a buzz of excitement, as history is made once again by this 37-year-old arts organization. Top pianists—a baker’s dozen of them from Boston and beyond—will share the spotlight in Bach’s The Art of Fugue. The Emmanuel Music concert will find these pianists bringing their own interpretative genius to the individual fugues that they play. Each fugue is a complex, textural piece of music that weaves a variety of voices together. The Art of Fugue promises to provide another unforgettable Emmanuel Music night, since this complex, mysterious and infrequently performed study of fugal counterpoint has fascinated scholars, historians, performers and audiences for nearly 260 years. Bach worked on the piece for more than a decade, probably from the late 1730s to his death in 1750, and it was published the following year. Its formal title is Die Kunst der Fuge, BWV 1080. As a youth, Bach had already started experimenting with the fugal form, and The Art of Fugue stands as the pinnacle of his keyboard genius. Craig Smith, Emmanuel Music Conductor and Artistic Director, is the creative force behind The Art of Fugue concert. Among the pianists are John Harbison, distinguished composer and Emmanuel Music Principal Guest Conductor; Robert Levin, a performer known around the globe; and Emmanuel Music regulars, husband and wife, Randall Hodgkinson and Leslie Amper. Other familiar musicians who have participated in Emmanuel Music Chamber Series and other collaborations over the years will be on hand, along with some exciting new pianists. -

Ensemble Parallèle Presents the Great Gatsby by John Harbison February 10, 11 and 12, 2012 at San Francisco’S Yerba Buena Center for the Arts

ENSEMBLE PARALLÈLE PRESENTS THE GREAT GATSBY BY JOHN HARBISON FEBRUARY 10, 11 AND 12, 2012 AT SAN FRANCISCO’S YERBA BUENA CENTER FOR THE ARTS WORLD PREMIERE OF CHAMBER ORCHESTRATION BY JACQUES DESJARDINS FEATURES MARCO PANUCCIO, JASON DETWILER AND SUSANNAH BILLER San Francisco, September 19, 2011 -- Ensemble Parallèle will present the world premiere of Jacques Desjardins’ chamber orchestration of John Harbison’s The Great Gatsby on February 10, 11 and 12, 2012 at San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Novellus Theater. Artistic Director Nicole Paiement again collaborates with Stage Director and Production Designer Brian Staufenbiel to create their most ambitious project to date. Jacques Desjardins, a well-known Bay Area composer and orchestrator retains the rich sound of Harbison’s score while enhancing the story and providing the audience a more intimate and intense experience with this American literary classic. Based on the famed novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald, composer John Harbison’s The Great Gatsby was originally commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera and premiered in 1999 with subsequent performances at the Lyric Opera in Chicago. Ensemble Parallèle’s world premiere presentation of the chamber orchestration of The Great Gatsby marks the first time in ten years that this literary masterpiece will be given a musical life onstage. Lyric tenor Marco Panuccio, who portrayed Des Grieux in Massenet’s Manon for Lyric Opera of Chicago, heads the eleven member cast in the role of Jay Gatsby. Baritone Jason Detwiler, St. Plan in Ensemble Parallèle’s summer 2011 production of Four Saints in Three Acts, is Nick Carraway and soprano Susannah Biller, who portrayed Eurydice in Ensemble Parallèle’s spring 2011 production of Philip Glass’ Orphée, is featured as Daisy Buchanan. -

Introduction to the Great Gatsby F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 Novel The

Introduction to The Great Gatsby F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel The Great Gatsby is a tragic love story, a mystery, and a social commentary on American life. Although it was not a commercial success for Fitzgerald during his lifetime, this lyrical novel has become an acclaimed masterpiece read and taught throughout the world. Unfolding in nine concise chapters, The Great Gatsby concerns the wasteful lives of four wealthy characters as observed by their acquaintance, narrator Nick Carraway. Like Fitzgerald himself, Nick is from Minnesota, attended an Ivy League university, served in the U.S. Army during World War I, moved to New York after the war, and questions— even while participating in—high society. Having left the Midwest to work in the bond business in the summer of 1922, Nick settles in West Egg, Long Island, among the nouveau riche epitomized by his next-door neighbor Jay Gatsby. A mysterious man of thirty, Gatsby is the subject of endless fascination to the guests at his lavish all-night parties. He is rumored to be a hero of the Great War. Others say he served as a German spy. Gatsby claims to have attended Oxford University, but the evidence is suspect. As Nick learns more about Gatsby, every detail about him seems questionable, except his love for the charming Daisy Buchanan. Jay Gatsby's decadent parties are thrown with one goal: to attract Daisy, who lives across the bay in the more fashionable East Egg. From the lawn of his sprawling mansion, Gatsby can see the green light glowing on her dock, which becomes a symbol in the novel of an unreachable treasure, the "future that year by year recedes before us." Though Daisy is a married socialite and a mother, Gatsby still worships her as his "golden girl." They first met when she was a young lady from an affluent family and he was a working-class military officer.