Feathers to Fur the Ecological Transformation of Aotearoa/New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entomology of the Aucklands and Other Islands South of New Zealand: Lepidoptera, Ex Cluding Non-Crambine Pyralidae

Pacific Insects Monograph 27: 55-172 10 November 1971 ENTOMOLOGY OF THE AUCKLANDS AND OTHER ISLANDS SOUTH OF NEW ZEALAND: LEPIDOPTERA, EX CLUDING NON-CRAMBINE PYRALIDAE By J. S. Dugdale1 CONTENTS Introduction 55 Acknowledgements 58 Faunal Composition and Relationships 58 Faunal List 59 Key to Families 68 1. Arctiidae 71 2. Carposinidae 73 Coleophoridae 76 Cosmopterygidae 77 3. Crambinae (pt Pyralidae) 77 4. Elachistidae 79 5. Geometridae 89 Hyponomeutidae 115 6. Nepticulidae 115 7. Noctuidae 117 8. Oecophoridae 131 9. Psychidae 137 10. Pterophoridae 145 11. Tineidae... 148 12. Tortricidae 156 References 169 Note 172 Abstract: This paper deals with all Lepidoptera, excluding the non-crambine Pyralidae, of Auckland, Campbell, Antipodes and Snares Is. The native resident fauna of these islands consists of 42 species of which 21 (50%) are endemic, in 27 genera, of which 3 (11%) are endemic, in 12 families. The endemic fauna is characterised by brachyptery (66%), body size under 10 mm (72%) and concealed, or strictly ground- dwelling larval life. All species can be related to mainland forms; there is a distinctive pre-Pleistocene element as well as some instances of possible Pleistocene introductions, as suggested by the presence of pairs of species, one member of which is endemic but fully winged. A graph and tables are given showing the composition of the fauna, its distribution, habits, and presumed derivations. Host plants or host niches are discussed. An additional 7 species are considered to be non-resident waifs. The taxonomic part includes keys to families (applicable only to the subantarctic fauna), and to genera and species. -

Common Pathways by Which Non-Native Forest Insects Move

Journal of Pest Science (2019) 92:13–27 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-0990-0 REVIEW Common pathways by which non‑native forest insects move internationally and domestically Nicolas Meurisse1 · Davide Rassati2 · Brett P. Hurley3 · Eckehard G. Brockerhof4 · Robert A. Haack5 Received: 18 February 2018 / Revised: 29 April 2018 / Accepted: 12 May 2018 / Published online: 30 May 2018 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract International trade and movement of people are largely responsible for increasing numbers of non-native insect introductions to new environments. For forest insects, trade in live plants and transport of wood packaging material (WPM) are considered the most important pathways facilitating long-distance invasions. These two pathways as well as trade in frewood, logs, and processed wood are commonly associated with insect infestations, while “hitchhiking” insects can be moved on cargo, in the conveyances used for transport (e.g., containers, ships), or associated with international movement of passengers and mail. Once established in a new country, insects can spread domestically through all of the above pathways. Considerable national and international eforts have been made in recent years to reduce the risk of international movement of plant pests. International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures (ISPMs) No. 15 (WPM), 36 (plants for planting), and 39 (wood) are examples of phytosanitary standards that have been adopted by the International Plant Protection Convention to reduce risks of invasions of forest pests. The implementation of ISPMs by exporting countries is expected to reduce the arrival rate and establishments of new forest pests. However, many challenges remain to reduce pest transportation through international trade, given the ever-increasing volume of traded goods, variations in quarantine procedures between countries, and rapid changes in distribution networks. -

Protection of Pandora Moth (Coloradia Pandora Blake) Eggs from Consumption by Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrels (Spermophilus Lateralis Say)

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Elizabeth Ann Gerson for the degree of Master of Science in Forest Science presented on 10 January, 1995. Title: Protection of Pandora Moth (Coloradia pandora Blake) Eggs From Consumption by Golden-mantled Ground Squirrels (Spermophilus lateralis Say) Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy William C. McComb Endemic populations of pandora moths (Coloradia pandora Blake), a defoliator of western pine forests, proliferated to epidemic levels in central Oregon in 1986 and increased dramatically through 1994. Golden-mantled ground squirrels (Spermophilus lateralis Say) consume adult pandora moths, but reject nutritionally valuable eggs from gravid females. Feeding trials with captive S. lateralis were conducted to identify the mode of egg protection. Chemical constituents of fertilized eggs were separated through a polarity gradient of solvent extractions. Consumption of the resulting hexane, dichloromethane, and water egg fractions, and the extracted egg tissue residue, was evaluated by randomized 2-choice feeding tests. Consumption of four physically distinct egg fractions (whole eggs, "whole" egg shells, ground egg shells, and egg contents) also was evaluated. These bioassays indicated that C. pandora eggs are not protected chemically, however, the egg shell does inhibit S. lateralis consumption. Egg protection is one mechanism that enables C. pandora to persist within the forest food web. Spermophilus lateralis, a common and often abundant rodent of central Oregon pine forests, is a natural enemy of C. pandora -

Molecular Basis of Pheromonogenesis Regulation in Moths

Chapter 8 Molecular Basis of Pheromonogenesis Regulation in Moths J. Joe Hull and Adrien Fónagy Abstract Sexual communication among the vast majority of moths typically involves the synthesis and release of species-specifc, multicomponent blends of sex pheromones (types of insect semiochemicals) by females. These compounds are then interpreted by conspecifc males as olfactory cues regarding female reproduc- tive readiness and assist in pinpointing the spatial location of emitting females. Studies by multiple groups using different model systems have shown that most sex pheromones are synthesized de novo from acetyl-CoA by functionally specialized cells that comprise the pheromone gland. Although signifcant progress was made in identifying pheromone components and elucidating their biosynthetic pathways, it wasn’t until the advent of modern molecular approaches and the increased avail- ability of genetic resources that a more complete understanding of the molecular basis underlying pheromonogenesis was developed. Pheromonogenesis is regulated by a neuropeptide termed Pheromone Biosynthesis Activating Neuropeptide (PBAN) that acts on a G protein-coupled receptor expressed at the surface of phero- mone gland cells. Activation of the PBAN receptor (PBANR) triggers a signal trans- duction cascade that utilizes an infux of extracellular Ca2+ to drive the concerted action of multiple enzymatic steps (i.e. chain-shortening, desaturation, and fatty acyl reduction) that generate the multicomponent pheromone blends specifc to each species. In this chapter, we provide a brief overview of moth sex pheromones before expanding on the molecular mechanisms regulating pheromonogenesis, and con- clude by highlighting recent developments in the literature that disrupt/exploit this critical pathway. J. J. Hull (*) USDA-ARS, US Arid Land Agricultural Research Center, Maricopa, AZ, USA e-mail: [email protected] A. -

Pu'u Wa'awa'a Biological Assessment

PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A, NORTH KONA, HAWAII Prepared by: Jon G. Giffin Forestry & Wildlife Manager August 2003 STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF FORESTRY AND WILDLIFE TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE ................................................................................................................................. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. ii GENERAL SETTING...................................................................................................................1 Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Land Use Practices...............................................................................................................1 Geology..................................................................................................................................3 Lava Flows............................................................................................................................5 Lava Tubes ...........................................................................................................................5 Cinder Cones ........................................................................................................................7 Soils .......................................................................................................................................9 -

Contribution to the Lepidoptera Fauna of the Madeira Islands Part 2

Beitr. Ent. Keltern ISSN 0005 - 805X 51 (2001) 1 S. 161 - 213 14.09.2001 Contribution to the Lepidoptera fauna of the Madeira Islands Part 2. Tineidae, Acrolepiidae, Epermeniidae With 127 figures Reinhard Gaedike and Ole Karsholt Summary A review of three families Tineidae, Epermeniidae and Acrolepiidae in the Madeira Islands is given. Three new species: Monopis henderickxi sp. n. (Tineidae), Acrolepiopsis mauli sp. n. and A. infundibulosa sp. n. (Acrolepiidae) are described, and two new combinations in the Tineidae: Ceratobia oxymora (MEYRICK) comb. n. and Monopis barbarosi (KOÇAK) comb. n. are listed. Trichophaga robinsoni nom. n. is proposed as a replacement name for the preoccupied T. abrkptella (WOLLASTON, 1858). The first record from Madeira of the family Acrolepiidae (with Acrolepiopsis vesperella (ZELLER) and the two above mentioned new species) is presented, and three species of Tineidae: Stenoptinea yaneimarmorella (MILLIÈRE), Ceratobia oxymora (MEY RICK) and Trichophaga tapetgella (LINNAEUS) are reported as new to the fauna of Madeira. The Madeiran records given for Tsychoidesfilicivora (MEYRICK) are the first records of this species outside the British Isles. Tineapellionella LINNAEUS, Monopis laevigella (DENIS & SCHIFFERMULLER) and M. imella (HÜBNER) are dele ted from the list of Lepidoptera found in Madeira. All species and their genitalia are figured, and informa tion on bionomy is presented. Zusammenfassung Es wird eine Übersicht über die drei Familien Tineidae, Epermeniidae und Acrolepiidae auf den Madeira Inseln gegeben. Die drei neuen Arten Monopis henderickxi sp. n. (Tineidae), Acrolepiopsis mauli sp. n. und A. infundibulosa sp. n. (Acrolepiidae) werden beschrieben, zwei neue Kombinationen bei den Tineidae: Cerato bia oxymora (MEYRICK) comb. -

Intensified Agriculture Favors Evolved Resistance to Biological Control

Intensified agriculture favors evolved resistance to biological control Federico Tomasettoa,1, Jason M. Tylianakisb,c, Marco Realed, Steve Wrattene, and Stephen L. Goldsona,e aAgResearch Ltd., Christchurch 8140, New Zealand; bCentre for Integrative Ecology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Canterbury, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand; cDepartment of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Silwood Park Campus, Ascot, Berkshire SL5 7PY, United Kingdom; dSchool of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Canterbury, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand; and eBio-Protection Research Centre, Lincoln University, Lincoln 7647, New Zealand Edited by May R. Berenbaum, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL, and approved February 14, 2017 (received for review November 6, 2016) Increased regulation of chemical pesticides and rapid evolution of source–sink evolutionary dynamics whereby vulnerable genotypes pesticide resistance have increased calls for sustainable pest are maintained by immigration from refuges (16). In addition, management. Biological control offers sustainable pest suppres- combinations of different enemy species may exert separate se- sion, partly because evolution of resistance to predators and lective pressures, and thereby prevent the pest from evolving re- parasitoids is prevented by several factors (e.g., spatial or tempo- sistance to any single enemy across its entire range (17). ral refuges from attacks, reciprocal evolution by control agents, However, these mechanisms that prevent resistance to biological and contrasting selection pressures from other enemy species). control could in theory be undermined in large-scale homoge- However, evolution of resistance may become more probable as neous agricultural systems, which may have few refuges to sustain agricultural intensification reduces the availability of refuges and susceptible strains of the pest, low variability in attack rates, and diversity of enemy species, or if control agents have genetic low biodiversity of enemy species (9). -

The Painted Apple Moth Eradication Programme (B)

CASE PROGRAM 2006-10.2 The Painted Apple Moth Eradication Programme (B) In late August 2002, Murray Sherwin, Director-General of the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) had to decide whether to reverse his department’s recommendation, made to Cabinet barely a month before, for the future management of the Painted Apple Moth (PAM) incursion. The fast-breeding moth, discovered three years earlier, threatened New Zealand’s plantation forests as well as its native bush, potentially robbing the economy of $356 million in exports. Despite eradication efforts, including the controversial use of aerial sprays, new areas of infestation were still being discovered. Murray Sherwin had become chief executive less than a year ago, arriving at MAF as controversy was building around his Forest Biosecurity Group’s management of PAM. MAF’s recommendation to Cabinet in July 2002, based on the weight of internal and external advice, and concern about the $90 million estimated cost of an all-out eradication attempt, was to continue with containment activities while further investigating other means of managing the pest. Government’s response was to allocate $11 million in immediate resources and call for more detailed information on the options of long-term management, or a renewed attempt at full eradication. Sherwin realised there was substantial political support, despite the odds, for eradication. He now needed to know whether his department, besieged by media and community criticism, could believe in and commit to the task. This case was developed by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG) and funded by the New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF). -

Yellow Admiral (Vanessa Itea)

Yellow Admiral (Vanessa itea) Wingspan ~50mm Photo: Tony Morton Note 1: The upper side of wings shown in butterfly on the left. The underside of the wings shown in the butterfly on the left. Males and females are similar. Note 2: The plant name on the bottom right refers to the plants upon which the butterfly larvae (caterpillars) feed. Other Common Names: Australian Admiral, Admiral Family of Butterflies: Nymphalidae (Browns and Nymphs) Tony Morton’s documented records of Yellow Admiral from the local area (between 2000 to 2013): Seven Date Location Notes 21-Sep-2000 Vaughan 28-Sep-2000 Irishtown Track, Irishtown 17-Oct-2003 Vaughan 5-Sep-2005 Vaughan walk fresh 1 Butterflies of the Mount Alexander Shire – A Castlemaine Field Naturalists Club publication Date Location Notes Between Jan 2005 to Oct 2006 Kalimna Park 27-Mar-2012 Kalimna Point on sap oozing from Small Sugar Gum(?) 29-Aug-2013 Vaughan garden Other documented local observations: None Distribution Across Victoria (from Field 2013): Observations from across Victoria. Larval Host Plants (Field 2013): Shade Pellitory (Parietaria debilis) and nettles, including the introduced Stinging Nettle (Urtica urens) Larval association with ants (Field 2013): None. Adult Flight Times in Victoria (from Field 2013): Adults have been recorded during all months in Victoria, with a peak from September to January. Usually one of the first spring butterflies in Victoria.F Fly fast, and close to ground. Bask with wings open. Several generations completed each year. Conservation Status: National Butterfly Action Plan (2002): No conservation status Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: Not listed Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988: Not listed Advisory List of Threatened Victorian Invertebrates (DSE 2009): Not listed Other Notes: Likely to be resident and moderately common the Mount Alexander Shire, particular in urban areas and wetter locations supporting nettles. -

Contribution to the Lepidopterans of Visakhapatnam Region, Andhra Pradesh, India

ANALYSIS Vol. 21, Issue 68, 2020 ANALYSIS ARTICLE ISSN 2319–5746 EISSN 2319–5754 Species Contribution to the Lepidopterans of Visakhapatnam Region, Andhra Pradesh, India Solomon Raju AJ1, Venkata Ramana K2 1Department of Environmental Sciences, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam 530 003, India 2Department of Botany, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam 530 003, India Corresponding author: A.J. Solomon Raju, Department of Environmental Sciences, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam 530 003, India Mobile: 91-9866256682, email: [email protected] Article History Received: 28 June 2020 Accepted: 02 August 2020 Published: August 2020 Citation Solomon Raju AJ, Venkata Ramana K. Contribution to the Lepidopterans of Visakhapatnam Region, Andhra Pradesh, India. Species, 2020, 21(68), 275-280 Publication License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. General Note Article is recommended to print as color digital version in recycled paper. ABSTRACT The butterflies Byblia ilithyia (Nymphalidae), Pieris canidia (Pieridae) and Azanus jesous (Lycaenidae) and the day-flying moth, Nyctemera adversata (Erebidae) are oligophagous. Previously, only B. ilithyia has been reported to be occurring in this region while the other three species are being reported for the first time from this region. The larval host plants include Jatropha gossypiifolia and Tragia involucrata for B. ilithyia, Brassica oleracea var. oleracea and B. oleracea var. botrytis for P. canidia, and Acacia auriculiformis for Azanus jesous. The nectar plants include Tragia involucrata, Euphorbia hirta and Jatropha gossypiifolia for B. ilithyia, Premna latifolia and Cleome viscosa for P. canidia, Lagascea mollis, Tridax procumbens and Digera muricata for A. jesous and Bidens pilosa for 275 N. adversata. The study recommends extensive field investigations to find out more larval plants and nectar plants for each Page lepidopteran species now reported. -

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

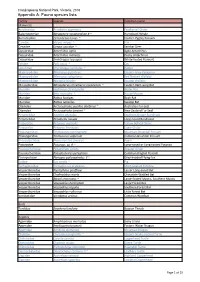

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus -

Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and Evolutionary Correlates of Novel Secondary Sexual Structures

Zootaxa 3729 (1): 001–062 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3729.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:CA0C1355-FF3E-4C67-8F48-544B2166AF2A ZOOTAXA 3729 Phylogeny of the tribe Archipini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and evolutionary correlates of novel secondary sexual structures JASON J. DOMBROSKIE1,2,3 & FELIX A. H. SPERLING2 1Cornell University, Comstock Hall, Department of Entomology, Ithaca, NY, USA, 14853-2601. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, T6G 2E9 3Corresponding author Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by J. Brown: 2 Sept. 2013; published: 25 Oct. 2013 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 JASON J. DOMBROSKIE & FELIX A. H. SPERLING Phylogeny of the tribe Archipini (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae: Tortricinae) and evolutionary correlates of novel secondary sexual structures (Zootaxa 3729) 62 pp.; 30 cm. 25 Oct. 2013 ISBN 978-1-77557-288-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-289-3 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2013 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2013 Magnolia Press 2 · Zootaxa 3729 (1) © 2013 Magnolia Press DOMBROSKIE & SPERLING Table of contents Abstract . 3 Material and methods . 6 Results . 18 Discussion . 23 Conclusions . 33 Acknowledgements . 33 Literature cited . 34 APPENDIX 1. 38 APPENDIX 2. 44 Additional References for Appendices 1 & 2 . 49 APPENDIX 3. 51 APPENDIX 4. 52 APPENDIX 5.