How Australia's Leading Women's Magazines Portray the Postpartum 'Body'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australia 2017 Contents

DIGITAL NEWS REPORT: AUSTRALIA 2017 CONTENTS FOREWORD Jerry Watkins 2 ABOUT: METHODOLOGY 3 RESEARCH TEAM 4 1 KEY FINDINGS Sora Park 6 COMMENTARY: A BRITISH VIEW OF THE AUSTRALIAN LANDSCAPE David Levy 16 2 AUSTRALIA BY COMPARISON Jerry Watkins 18 COMMENTARY: “YOU ARE FAKE NEWS!” Natasha Eves 25 COMMENTARY: FOCUS: EAST ASIA MARKETS Francis Lee 26 3 NEWS ACCESS & CONSUMPTION R. Warwick Blood and Jee Young Lee 28 COMMENTARY: GOING WHERE THE AUDIENCE GOES Dan Andrew 34 4 SOCIAL DISCOVERY OF NEWS Glen Fuller 36 5 FOLLOWING POLITICIANS ON SOCIAL MEDIA Caroline Fisher 42 COMMENTARY: BEYOND THE ECHO CHAMBER Andrew Leigh MP 48 6 PAYING FOR ONLINE NEWS Franco Papandrea 50 COMMENTARY: PAYING FOR NEWS IN A WORLD OF CHOICE Richard Bean 57 7 TRUST IN NEWS: AUSTRALIA Caroline Fisher and Glen Fuller 58 COMMENTARY: A BROKEN RELATIONSHIP Karen Barlow 68 SPECIAL SECTION: GENDER AND NEWS 70 COMMENTARY: A VESSEL FOR FRUIT Jacqueline Maley 72 8 GENDERED SPACES OF NEWS CONSUMPTION Michael Jensen and Virginia Haussegger 74 9 ESSAY: ‘WHAT’S GENDER GOT TO DO WITH IT?’ Virginia Haussegger 80 COMMENTARY: GENDER AND NEWS: MYTHS AND REALITY Pia Rowe 83 DIGITAL NEWS REPORT: AUSTRALIA 2017 by Jerry Watkins, Sora Park, Caroline Fisher, R. Warwick Blood, Glen Fuller, Virginia Haussegger, Michael Jensen, Jee Young Lee and Franco Papandrea. NEWS & MEDIA RESEARCH CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA NEWS & MEDIA RESEARCH CENTRE FOREWORD Jerry Watkins Director, News & Media Research Centre, University of Canberra Lead author, Digital News Report: Australia 2017 At time of writing, the Australian terrestrial TV player So both broadcast and print players are under TEN Network faces financial insolvency. -

Stephen Harrington Thesis

PUBLIC KNOWLEDGE BEYOND JOURNALISM: INFOTAINMENT, SATIRE AND AUSTRALIAN TELEVISION STEPHEN HARRINGTON BCI(Media&Comm), BCI(Hons)(MediaSt) Submitted April, 2009 For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology, Australia 1 2 STATEMENT OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made. _____________________________________________ Stephen Matthew Harrington Date: 3 4 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the changing relationships between television, politics, audiences and the public sphere. Premised on the notion that mediated politics is now understood “in new ways by new voices” (Jones, 2005: 4), and appropriating what McNair (2003) calls a “chaos theory” of journalism sociology, this thesis explores how two different contemporary Australian political television programs (Sunrise and The Chaser’s War on Everything) are viewed, understood, and used by audiences. In analysing these programs from textual, industry and audience perspectives, this thesis argues that journalism has been largely thought about in overly simplistic binary terms which have failed to reflect the reality of audiences’ news consumption patterns. The findings of this thesis suggest that both ‘soft’ infotainment (Sunrise) and ‘frivolous’ satire (The Chaser’s War on Everything) are used by audiences in intricate ways as sources of political information, and thus these TV programs (and those like them) should be seen as legitimate and valuable forms of public knowledge production. -

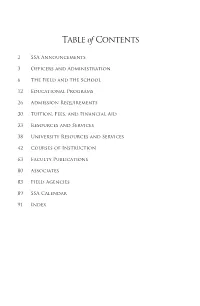

Social Service Administration 2019-2020

Table of Contents 2 SSA Announcements 3 Officers and Administration 6 The Field and the School 12 Educational Programs 26 Admission Requirements 30 Tuition, Fees, and Financial Aid 33 Resources and Services 38 University Resources and Services 42 Courses of Instruction 63 Faculty Publications 80 Associates 83 Field Agencies 89 SSA Calendar 91 Index 2 SSA Announcements SSA Announcements Please use the left-hand navigation bar to access the individual pages for the SSA Announcements. In keeping with its long-standing traditions and policies, the University of Chicago considers students, employees, applicants for admission or employment, and those seeking access to University programs on the basis of individual merit. The University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national or ethnic origin, age, status as an individual with a disability, protected veteran status, genetic information, or other protected classes under the law (including Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972). For additional information regarding the University of Chicago’s Policy on Harassment, Discrimination, and Sexual Misconduct, please see: http://harassmentpolicy.uchicago.edu/page/policy. The University official responsible for coordinating compliance with this Notice of Nondiscrimination is Bridget Collier, Associate Provost and Director of the Office for Equal Opportunity Programs. Ms. Collier also serves as the University’s Title IX Coordinator, Affirmative Action Officer, and Section 504/ADA Coordinator. You may contact Ms. Collier by emailing [email protected], by calling 773.702.5671, or by writing to Bridget Collier, Office of the Provost, The University of Chicago, 5801 S. Ellis Ave., Suite 427, Chicago, IL 60637. -

2016-2017 University of Chicago 3

T he U niversity o f C hicago School of Social Service Administration Announcements 2016-2017 Table of Contents 2 SSA Announcements 3 Officers and Administration 7 The Field and the School 17 Educational Programs 42 Admission Requirements 49 Tuition, Fees, and Financial Aid 54 Resources and Services 62 University Resources and Services 70 Courses of Instruction 112 Faculty Publications 158 Associates 161 Field Agencies 168 SSA Calendar 170 Index 2 SSA Announcements SSA Announcements Please use the left-hand navigation bar to access the individual pages for the SSA Announcements. In keeping with its long-standing traditions and policies, the University of Chicago considers students, employees, applicants for admission or employment, and those seeking access to University programs on the basis of individual merit. The University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national or ethnic origin, age, status as an individual with a disability, protected veteran status, genetic information, or other protected classes as required by law (including Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972). For additional information regarding the University of Chicago’s Policy on Harassment, Discrimination, and Sexual Misconduct, please see: http://harassmentpolicy.uchicago.edu/page/policy. The University official responsible for coordinating compliance with this Notice of Nondiscrimination is Sarah Wake, Associate Provost and Director of the Office for Equal Opportunity Programs. Ms. Wake also serves as the University’s Title IX Coordinator, Affirmative Action Officer, and Section 504/ADA Coordinator. You may contact Ms. Wake by emailing [email protected], by calling 773.702.5671, or by writing to Sarah Wake, Office of the Provost, The University of Chicago, 5801 S. -

Jessica Rowe's Biography

Jessica Rowe Journalist, broadcaster, bestselling author, mental health awareness advocate and proud Crap Housewife. Biography Jessica Rowe is an accomplished journalist, television presenter and three-time Follow bestselling author. Jessica’s credits include co-hosting Studio 10 (Ten) and The Jessica Today Show (Nine). She was also the news presenter for Weekend Sunrise (Seven), and for a decade Jessica co-hosted Network Ten’s First at Five News. Instagram Facebook As a published author, Jessica has written a collection of memoirs centred Twitter around her experiences with post natal depression, motherhood and parenting. O"icial Website Her titles include The Best of Times, The Worst of Times, Love. Wisdom. Motherhood., Is This My Beautiful Life? and most recently Diary of a Crap Housewife. Further Jess is a self confessed Crap Housewife. She has gathered a strong and loyal Information following with her online Crap Housewife movement, one that unites and Jessica Rowe is celebrates other mothers who, like Jess, sometimes feel like they are not the exclusively managed perfect mother, wife or cook. With humour and honesty, Jess shares her amusing by Watercooler Talent. misadventures at Crap Housewife and her Instagram channel. For all enquires please As a podcaster, Jess has produced and hosted the comedy and lifestyle series get in touch. One Fat Lady and One Thin Lady with her best friend, Denise Drysdale. The series debuted as the No. 1 podcast (All Categories) on Apple Podcast AU in March 2018. Jess also hosted Kidspot’s Mummy Mentors podcast series (2020). In addition to her anchor and journalist TV roles, Jess has been able to show her fun-loving nature in light entertainment TV roles. -

LOVE. WISDOM. MOTHERHOOD. Jessica Rowe

LOVE. WISDOM. MOTHERHOOD. Jessica Rowe Sharing the wisdom of twelve inspiring Australian women, this is a heart-warming and revealing look at motherhood – a unique mother’s group on the page for women looking for honesty about what to expect and the support to know they are not doing it wrong! • How many other mums are feeling like me? Happy, bored, exhausted, writing mental notes, dreaming of Paris, getting lost? • How do you balance children, life, relationships and work? • Why do women feel the need to justify being a mother as a job? And why hide the struggles faced? • Why are we so quick to judge other women and the choices they have made? When these questions kept coming up for Jessica Rowe after the birth of her first daughter, she realised that she wasn’t be the only new mother facing the expected – and often entirely surprising – challenges of mothering. And, while the perennial question women pose is ‘Can I have it all?’ she soon realised the truer question was ‘Can I get through this?’ She wanted to speak to other women to ask if they faced the same issues. Did they struggle in the early months? Did they worry their career was over? Did they feel guilty about going back to work? How did they make time for their partner? And, what does being a mum mean to them? She chose eleven extraordinary Australian women admired by us all, and through exceptionally honest conversations with Lisa McCune, Heidi Middleton, Elizabeth Broderick, Wendy Harmer, Collette Dinnigan, Maggie Tabberer, Tina Arena, Quentin Bryce, Nova Peris, Gail Kelly, Darcey Bussell and a chapter from Jessica herself, she reveals the obstacles they encountered along the way, the happiness and the heartache, the myths and the realities, and the ultimately joyous and shared nature of the motherhood journey. -

Sydney Writers' Festival

Bibliotherapy LET’S TALK WRITING 16-22 May 1HERSA1 S001 2 swf.org.au SYDNEY WRITERS’ FESTIVAL GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES SUPPORTERS Adelaide Writers’ Week THE FOLLOWING PARTNERS AND SUPPORTERS Affirm Press NSW Writers’ Centre Auckland Writers & Readers Festival Pan Macmillan Australia Australian Poetry Ltd Penguin Random House Australia The Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance Perth Writers Festival CORE FUNDERS Black Inc. Riverside Theatres Bloomsbury Publishing Scribe Publications Brisbane Powerhouse Shanghai Writers’ Association Brisbane Writers Festival Simmer on the Bay Byron Bay Writers’ Festival Simon & Schuster Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre State Library of NSW Créative France The Stella Prize Griffith REVIEW Sydney Dance Lounge Harcourts International Conference Text Publishing Hardie Grant Books University of Queensland Press MAJOR PARTNERS Hardie Grant Egmont Varuna, the National Writers’ House HarperCollins Publishers Walker Books Hachette Australia The Walkley Foundation History Council of New South Wales Wheeler Centre Kinderling Kids Radio Woollahra Library and Melbourne University Press Information Service Musica Viva Word Travels PLATINUM PATRON Susan Abrahams The Russell Mills Foundation Rowena Danziger AM & Ken Coles AM Margie Seale & David Hardy Dr Kathryn Lovric & Dr Roger Allan Kathy & Greg Shand Danita Lowes & David Fite WeirAnderson Foundation GOLD PATRON Alan & Sue Cameron Adam & Vicki Liberman Sally Cousens & John Stuckey Robyn Martin-Weber Marion Dixon Stephen, Margie & Xavier Morris Catherine & Whitney Drayton Ruth Ritchie Lisa & Danny Goldberg Emile & Caroline Sherman Andrea Govaert & Wik Farwerck Deena Shiff & James Gillespie Mrs Megan Grace & Brighton Grace Thea Whitnall PARTNERS The Key Foundation SILVER PATRON Alexa Haslingden David Marr & Sebastian Tesoriero RESEARCH & ENGAGEMENT Susan & Jeffrey Hauser Lawrence & Sylvia Myers Tony & Louise Leibowitz Nina Walton & Zeb Rice PATRON Lucinda Aboud Ariane & David Fuchs Annabelle Bennett Lena Nahlous James Bennett Pty Ltd Nicola Sepel Lucy & Stephen Chipkin Eva Shand The Dunkel Family Dr Evan R. -

The True Story of Maddie Bright Mary-Rose Maccoll

AUSTRALIA APRIL 2019 The True Story of Maddie Bright Mary-Rose MacColl The bestselling author of In Falling Snow returns with a spellbinding tale of friendship, love and loyalty Description 'This book has it all: an unforgettable first chapter, a fascinating insight into the Prince of Wales' visit to Australia in 1920 through the eyes of two women who worked for him, and a compelling mystery set in contemporary times, against the backdrop of Princess Diana's death. Truly wonderful storytelling.' - Natasha Lester, bestselling author of The Paris Seamstress In 1920, at seventeen years of age, Maddie Bright takes a job as a serving girl on the Royal Tour of Australia by Edward, Prince of Wales. She meets the prince's young staff - his vivacious press secretary Helen Burns, his most loyal man Rupert Waters - and the prince himself - beautiful, boyish, godlike. Maddie might be on the adventure of a lifetime. Sixty-one years later, Maddie Bright is living a small life in a ramshackle house in Paddington, Brisbane. But an unlooked- for letter has arrived in the mail and there's news on the television from Buckingham Palace that makes her shout back at the screen. Maddie Bright's true story may change. In August 1997, London journalist Victoria Byrd is tasked by her editor with the job of finding the elusive M.A. Bright, author of the classic war novel of ill-fated love, Autumn Leaves. It seems Bright has written a second novel, and Victoria has been handed the scoop. Recently engaged to an American film star, Victoria is horrified by her own sudden celebrity and keen to escape to Australia to follow the story. -

Pitching the Feminist Voice: a Critique of Contemporary Consumer Feminism

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 11-3-2017 10:30 AM Pitching the Feminist Voice: A Critique of Contemporary Consumer Feminism Kate Hoad-Reddick The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Romayne Smith Fullerton The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Kate Hoad-Reddick 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hoad-Reddick, Kate, "Pitching the Feminist Voice: A Critique of Contemporary Consumer Feminism" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5093. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5093 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This dissertation’s object of study is the contemporary trend of femvertising, where seemingly pro-women sentiments are used to sell products. I argue that this commodified version of feminism is highly curated, superficial, and docile, but also popular with advertisers and consumers alike. The core question at the centre of this research is how commercial feminism—epitomized by the trend of femvertising—influences the feminist discursive field. Initially, I situate femvertising within the wider trend of consumer feminism and consider the implications of a marketplace that speaks the language of feminism. -

Boys Will Be Boys

PRAISE FOR BOYS WILL BE BOYS ‘A damning look at toxic masculinity. It’s the most important thing you’ll read this year.’ Elle Australia ‘Boys Will Be Boys is a timely contribution to feminist literature. Her central point is clear and confronting, and it represents something of a challenge… Ferocious, incisive, an effective treatise.’ Australian Book Review ‘A piercing gaze at contemporary patriarchy, gendered oppression and toxic masculinity.’ Sydney Morning Herald ‘A truly vital piece of social commentary from Australia’s fiercest feminist, Boys Will Be Boys should be shoved into the hands of every person you know. Clementine Ford has done her research—despite what her angry detractors would have you believe—and spits truths about toxic masculinity and the dangers of the patriarchy with passion and a wonderfully wry sense of humour. Read it, learn from it, and share it—this book is absolute GOLD!’ AU Review, 16 Best Books of 2018 ‘Boys Will Be Boys is an impassioned call for societal change from a writer who has become a stand-out voice of her generation (and has the trolls to prove it) and an act of devotion from a mother to her son.’ Readings ‘With pithy jokes and witty commentary, this is an engrossing read, and Ford’s spirited tone evokes passion for change.’ Foreword Reviews ‘Clementine Ford reveals the fragility behind “toxic masculinity” in Boys Will Be Boys.’ The Conversation ‘Boys Will Be Boys highlights the need to refocus on how we’re raising our boys to be better men. The ingrained toxic masculinity within society does just as much damage to our boys as it does to our girls, and this book highlights how to change that.’ Fernwood Magazine PRAISE FOR FIGHT LIKE A GIRL ‘Her brilliant book could light a fire with its fury. -

2010–2011 Seminars

2010–2011 SEMINARS elow is a listing of the 2010–2011 University Seminars, with their topics and speakers. The seminars are Blisted in order of their Seminar Number, which roughly follows their chronological founding. Some of our seminars are still going strong after more than 60 years; new ones continue to be formed. One seminar was in - augurated last year. Seminars sometimes stop meeting, temporarily or permanently, for practical or intellec - tual reasons. Those that did not meet this past year are listed at the end of this section. Our seminars span a wide range of interests, from contemporary and historical topics in religion, literature, and law, to technical and administrative issues in contemporary society, to area studies, Shakespeare and the sciences. THE PROBLEM OF PEACE (403) Founded: 1945 This seminar is concerned broadly with the maintenance of international peace and security and with the set - tlement of international disputes. It considers specific conflicts and also discusses the contemporary role of the United Nations, multinational peacekeeping, humanitarian efforts, and other measures for the resolution of international conflicts. Chair: Professor Roy Lee Rapporteur: Ms. Tanya O’Carroll MEETINGS 2010–2011 September 14 The Current Situation in Iraq Jehangir Khan, Deputy Director, Middle East and Asia Division, UN Department of Political Affairs October 19 Disarmament Randy Rydell, Senior Political Affairs Officer, UN Office for Disarmament Affairs December 14 Development in Afghanistan Zahur Tanin, Permanent Representative of the UN for Afghanistan March 23 Recent Developments in Tunisia Ambassador Ghazi Jomaa, Permanent Representative of Tunisia to the UN Academic year 2011–2012 Chair: Professor Roy Lee, [email protected] Directory of Seminars, Speakers, and Topics 2010–2011 49 STUDIES IN RELIGION (405) Founded: 1945 The approaches to religion in this seminar range from the philosophical through the anthropological to the historical and comparative. -

APRIL 2019 Phillip Bradley Wilbur Smith N Ew Book S the TRUE STORY of MADDIE BRIGHT Mary-Rose Maccoll

Fleur McDonald Mary-Rose MacColl Elizabeth Coleman Jessica Rowe Kitty Flanagan Urzila Carlson APRIL 2019 Phillip Bradley Wilbur Smith n ew book s THE TRUE STORY OF MADDIE BRIGHT Mary-Rose MacColl ALLEN & UNWIN 9781760295240 | $29.99 | | PB | FICTION ALLEN & UNWIN The bestselling author of In Falling Snow returns with a spellbinding tale of friendship, love and loyalty In 1920, at seventeen years of age, Maddie Bright takes a job as a serving girl on the Royal Tour of Australia by Edward, Prince of Wales. She meets the prince's young staff and the prince himself— beautiful, boyish, godlike. Maddie might be on the adventure of a lifetime. Sixty-one years later, Maddie Bright is living a small life in a ramshackle house in Brisbane. But an unlooked-for letter has arrived in the mail and there's news on the television from Buckingham Palace that makes her shout back at the screen. Maddie Bright's true story may change. In August 1997, London journalist Victoria Byrd is tasked by her editor with the job of finding the elusive M.A. Bright, author of the classic war novel of ill-fated love, Autumn Leaves. It seems Bright has written a second novel and Victoria has been handed the scoop. Written with real warmth and wit, these evocative strands twist across the seas and over two continents, intersecting with the lives of Edward and Princess Diana, two of the most hated and loved figures of the twentieth century. The True Story of Maddie Bright is a novel that tells stories and reveals truth; a novel that considers the inescapable ties of mothering, friendship, duty and love.