Brickmaking in Pocklington & District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Instrument of Government

INSTRUMENT OF GOVERNMENT 1. The name of the school is St. Martin’s Church of England Voluntary Aided Primary School, Fangfoss. 2. The school is a voluntary aided school. 3. The name of the governing body is The Governing Body of St. Martin’s Church of England Voluntary Aided Primary School, Fangfoss. 4. The governing body shall consist of: 1 Headteacher; 1 Staff governor; 1 Local Authority governor; 2 Parent governors; 7 Foundation governors. 5. The total number of governors is 12. 6. Foundation governors are appointed by the York Diocesan Board of Education after consultation with the Parochial Church Councils of Fangfoss and Yapham. 7. (a) The holder of the following office shall be a foundation governor ex-officio: The Principal Officiating Minister of the Parish of Fangfoss. (b) The Archdeacon of York shall be entitled appoint a foundation governor to act in the place of the ex-officio foundation governor whose governorship derives from the office named in (a) above, in the event that the ex-officio foundation governor is unable or unwilling to act as a foundation governor, or where there is a vacancy in the office by virtue of which his or her governorship exists. 8. The Archdeacon of York is entitled to request the removal of any ex-officio foundation governor and to appoint any substitute governor. 9. The ethos of the school is as follows: “Recognising its historic foundation, the school will preserve and develop its religious character in accordance with the principles of the Church of England and in partnership with the Church at parish and diocesan level. -

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County

House Number Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town/Area County Postcode 64 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 70 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 72 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 74 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 80 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 82 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 84 Abbey Grove Well Lane Willerby East Riding of Yorkshire HU10 6HE 1 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 2 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 3 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 4 Abbey Road Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 4TU 1 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 3 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 5 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 7 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 9 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 11 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 13 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 15 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 17 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 19 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 21 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 23 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 7NA 25 Abbotts Way Bridlington East Riding of Yorkshire YO16 -

Fangfoss, Nr York 17.59 Acres

FANGFOSS , NR YORK 17.59 ACRES (7.12 HECTARES) Productive Grazing , adjoining the village of Fangfoss, situated east of York FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY Basic Payment Scheme : General Information We understand the land is registered with the Rural Payments Agency and the entitlements Situation: for the land are included in the sale. The land lies to the north of the village of Fangfoss, directly east of Highfield Lane which runs between Pocklington and the A166. Nitrate Vulnerable Zones: The land falls within a designated Nitrate Vulnerable Zone. Description: The extent of the land is shown edged red on the attached plan and comprises two parcels of land extending to 17.59 Acres (7.12 Hectares) in total. The land is accessed from Highfield Environmental Schemes: Lane. There are no Agri- Environment schemes on the land. Rights of Way: Sporting and Mineral Rights: The vendor not aware of any public or private rights of way over the land. As far as the Vendors are aware these are included in the sale. Services: Overage: The land benefits from a separately metered water supply. We are not aware of any other The Vendors will reserve the right to receive 25% of any uplift in value on the purchaser services connected to the remainder of the land and all purchasers should make their own or successors in title obtaining planning consent for any use other than agricultural, enquiries in respect of services. horticultural or equestrian use for a period of 15 years. Wayleaves & Easements: As far as the Vendor is aware there are no wayleaves or easements over the land. -

ERN Nov 2009.Indb

WINNER OF THE GOOD COMMUNICATIONS AWARD 2008 FOR JOURNALISM EAST RIDING If undelivered please return to HG115, East Riding of Yorkshire Council, County Hall, Cross Street, Beverley, HU17 9BA Advertisement Feature At Last! A NEW FORM OF HEATING FROM GERMANY… NEWS Simple to install, Powerful, Economical, and no more servicing – EVER! n Germany & Austria more and are making that same decision! When more people are choosing to you see this incredible heating for NOVEMBER 2009 EDITION Iheat their homes and offices with yourself, you could be next! a very special form of electric Discover for yourself this incredible • FREE TO YOU heating in preference to gas, oil, lpg heating from Germany. Get your or any other form of conventional info pack right away by calling • PAID FOR BY central heating. Here in the UK Elti Heating on Bridlington ADVERTISING more and more of our customers 01262 677579. New ‘destination’ playpark one of best in East Riding IN THIS ISSUE BACKING THE BID Help us bring the World Cup to East Yorkshire PAGE 28 WIN A WEDDING Win your perfect day with a Heritage Coast wedding PAGE 23 WIN A CRUSHER ENCOURAGING MORE CHILDREN TO PLAY OUT: Councillor Chris Matthews, chairman of the council, Win a free crusher in our blue bins draw opens the new playpark at Haltemprice Leisure Centre, with local schoolchildren and Nippy the kangaroo to help you wash and squash PAGE 9 EXCITING NEW PLAYPARK OPENS BY Tom Du Boulay best facilities in the East Riding by £200,000 from the Department protection, said: “The new and gives children and young for Children, Schools and Families playpark is a state-of-the-art E. -

Walking & Outdoors Festival

Tourist Information Tourist Information Centres offer information on everything you need to get the most from your visit, including where to stay, attractions and local events. We also provide transport information, maps and guide books. Walking & Information on eating out and much more! An accommodation booking service is available by telephone, online and at all Outdoors centres. A warm welcome awaits you. Festival Humber Bridge TIC, Bridlington TIC Click on North Bank Viewing Area, 25 Prince Street, Ferriby Road, Hessle, Bridlington, YO15 2NP, www.visithullandeastyorkshire.com HU13 0LN, Tel: 01482 391634, for more information on the area Tel: 01482 640852, email: bridlington.tic@ 14th - 23rd email: humberbridge.tic@ eastriding.gov.uk eastriding.gov.uk Opening times during Open Daily during August August and September September 2012 and September - 09:00 to Monday to Saturday - Walking and Cycling Packs 13:00 and 13.30 to 17:00 09:30 to 17:30 and available at the Tourist Sunday - 09:30 to 17:00 Information Centres - Beverley TIC Including Tracker Packs 34 Butcher Row, Hull TIC Beverley, HU17 0AB, 1 Paragon Street, Hull Tel: 01482 391672, HU1 3NA email: beverley.tic@ Tel: 01482 223559 eastriding.gov.uk email: tourist.information@ Opening Times: Monday hullcc.co.uk to Friday - 09:30 to17:15 For upto date info - Saturday - 10:00 to 16:45 Malton TIC follow us on Twitter @VHEY_UK Sunday (August Only) - Malton Library, St Michael 11:00 to 15:00 Street, Malton YO17 7LJ Tel: 01653 600048 email: maltontic@ btconnect.com For accommodation information, click on visithullandeastyorkshire.com. Other useful sites include www.walkingtheriding.co.uk and www.nationaltrail.co.uk/yorkshirewoldsway Whilst every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of information detailed in this guide. -

Welcometo the August

1 2 WELCOME to the August / September 2020 edition of the Parish News. We trust that all our readers remain well. We have insights from one of our readers on lockdown and a reminder of the life of William Wilberforce, at a time when our society needs to continue to act to stop racism. The coronavirus is still with us so take care and stay alert. THE PARISH NEWS EDITORIAL TEAM Allerthorpe Penny Simmons 303832 [email protected] Mark Stageman 303862 [email protected] Barmby Moor Jackie Jeffery 303651 [email protected] Gail Turner 380250 [email protected] Fangfoss and Bolton Julia Cockman 369662 [email protected] Yapham-cum-Meltonby Elaine Stubbings 304773 [email protected] Thornton and Melbourne Rebecca Metcalfe 318562 [email protected] We welcome all articles but reserve the right to shorten or amend them. Whilst we are happy to publish unedited articles, in the spirit of freedom of speech, any views expressed are not necessarily those of the Parish News Editorial Team. 3 HEARING DOGS FOR DEAF PEOPLE As many of you may already know Hearing Dogs for Deaf People have a training centre in Bielby, however, their base is in Buckinghamshire. Bielby is their only other site, so it is great that we have a high calibre national charity on our doorstep. We have been volunteers for several years and the most rewarding aspect has been discovering the massive difference having a hearing dog makes to someone’s life. The charity highlights that people who are deaf can feel disconnected from friends and family and their communities and often suffer from isolation, stress, and loneliness. -

Busatlas.Uk Principal Inter-Urban Bus Routes MAP 29 NORTH LINCS & EAST YORKSHIRE © Busatlas.Uk April 2021

MALTON MAP 32 Castle Howard High 843 Settrington Helperthorpe Flamborough Flamborough Head Hutton Weaverthorpe 12 40 N.Yorks CC 190 Stillington Bulmer Welburn Cas 190 East Yorkshire 13 14 Beachcomer Blue Sheriff Duggleby West Lutton Hutton Low Hutton Go-Ahead Open Top (Summer) Huby North Cas Crambeck Kirby Cas Grimston BRIDLINGTON (Castle Line) Whitwell Grindalythe Carnaby Lilling on-the-Hill Wharram Sutton on le Street Haisthorpe the Forest Flaxton 843 45 Transdev York Ruston 45A Burton Reliance Parva 121 Fraisthorpe 40 Connexions Claxton Agnes 130 29 Cas 30 30X Haxby First Nafferton 136 Sand Hutton Barmston Stockton on Lissett Skelton the Forest Stamford Driffield Bridge Ulrome 19 1 Cas Full Sutton Bishop Wansford 843 Skipsea Sands Poppleton 13 747 Wilton 45 136 Skipsea Murton 10 747 45A 22 YORK Fangfoss North Dunnington Dalton Hutton Beeford 10 Bolton Skirlington Yapham 45A Bainton Cranswick North 412 Warter 46 Kexby 747 Frodingham 130 45 Wilberfoss X46 Atwick 843 Watton ZAP 13 Air Museum 45 Elvington 46 Barmby Pocklington Middleton on the Wolds 121 Brandesburton 42 18 Sutton Upon Moor 45 Hornsea Copman- 36 36 Derwent Seaton thorpe Naburn York Pullman Hayton 240 246 Scorborough Rolston YP Acaster Malbis Wheldrake 45 Leven Sigglesthorpe 21 46 Shiptonthorpe Catwick Escrick X46 Leconfield Mappleton Appleton Roebuck Thorganby Tickton 246 Long Riston Bishop Stillingfleet 415 18 MAP 28MAP 129 46 Market X46 Burton Kelfield Weighton 121 Skipwith 18 Beverley 122 Skirlaugh Cawood Riccall 246 Holme on Aldbrough Walkington Woodmansey 42 North -

A P P L Ic a T Io

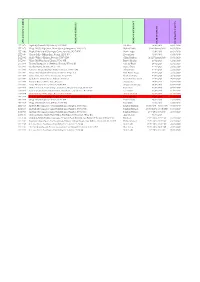

APPLICATION NUMBER NAME OF PREMISES NAME OF APPLICANT DATE EVENT OF DATE NOTICE GIVEN LTE1678 Highfield, Windmill Hill, Driffield, YO25 5YP Lily Slater 14/02/2020 04/02/2020 LTE1679 Village Hall, 59 High Street, Holme Upon Spalding Moor, YO43 4EN Richard Lindley 15-16 February 2020 04/02/2020 LTE1680 Firepit, Units 19 & 20 Flemingate Centre, Beverley, HU17 0PW Martin Angus 23/02/2020 09/02/2020 LTE1681 I-Bar & Grill, 1 Skillings Lane, Brough, HU15 1BA Emma Carter 23/02/2020 10/02/2020 LTE1682 Monk's Walk, 19 Highgate, Beverley, HU17 0DN Gillian Pickford 21-22 February 2020 10/02/2020 LTE1683 Village Hall, Main Street, Ellerton, YO42 4PB Dax Godderidge 21/02/2020 12/02/2020 LTE1684 Hornsea Museum, 11-17 Newbegin, Hornsea, HU18 1AB Timothy Bunch 20/02/2020 12/02/2020 LTE1685 Saturday Market, Beverley, HU17 8AA Sharron Davis 07/03/2020 24/02/2020 LTE1686 Pollington Village Hall, Main Street, Pollington, DN14 0DW Adrian Pettitt 07/03/2020 25/02/2020 LTE1687 Village Hall, Village Hall Road, North Dalton, YO25 9UX Nick Barker-Wyatt 06/03/2020 27/02/2020 LTE1688 Centre Farm, Main Street, Thornholme, YO25 4NN Charlotte Shipley 07/03/2020 28/02/2020 LTE1689 Jug & Bottle, 68 Main Street, Bubwith, YO8 6LX Louise Kathleen Smith 13/03/2020 05/03/2020 LTE1690 Howden Minster, Market Place, Howden Maynard Cox 14/03/2020 05/03/2020 LTE1691 Village Hall, Main Street, Ellerton, YO42 4PB Margaret Godderidge 20/03/2020 09/03/2020 LTE1692 J H Foreman Ltd, Station Garage, Main Street, Hutton Cranswick, YO25 9QY Fiona Bone 21/03/2020 09/03/2020 LTE1693 South -

East Riding Local Plan Strategy Document - Adopted April 2016 Contents

East Riding Local Plan 2012 - 2029 Strategy Document Adopted April 2016 DRAFT “Making It Happen” Contents FOREWORD v 1 INTRODUCTION 2 2 KEY SPATIAL ISSUES 8 3 VISION, PLACE STATEMENTS, OBJECTIVES & KEY DIAGRAM 18 THE SPATIAL STRATEGY 4 PROMOTING SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT 36 Promoting sustainable development 36 Addressing climate change 38 Focusing development 40 Supporting development in Villages and the Countryside 46 5 MANAGING THE SCALE AND DISTRIBUTION OF NEW DEVELOPMENT 52 Delivering housing development 52 Delivering employment land 60 Delivering retail development 65 Connecting people and places 68 DEVELOPMENT POLICIES 6 A HEALTHY AND BALANCED HOUSING MARKET 74 Creating a mix of housing 74 Providing affordable housing 78 Providing for the needs of Gypsies and Travellers 83 Making the most efficient use of land 85 7 A PROSPEROUS ECONOMY 90 Supporting the growth and diversification of the East Riding economy 90 Developing and diversifying the visitor economy 95 Supporting the vitality and viability of centres 100 Enhancing sustainable transport 105 Supporting the energy sector 108 Protecting mineral resources 116 East Riding Local Plan Strategy Document - Adopted April 2016 Contents 8 A HIGH QUALITY ENVIRONMENT 122 Integrating high quality design 122 Promoting a high quality landscape 127 Valuing our heritage 132 Conserving and enhancing biodiversity and geodiversity 136 Strengthening green infrastructure 143 Managing environmental hazards 147 9 A STRONG AND HEALTHY COMMUNITY 160 Providing infrastructure and facilities 160 Supporting -

U DDLG Papers of the Lloyd-Greame 12Th Cent. - 1950 Family of Sewerby

Hull History Centre: Papers of the Lloyd-Greame Family of Sewerby U DDLG Papers of the Lloyd-Greame 12th cent. - 1950 Family of Sewerby Historical Background: The estate papers in this collection relate to the manor of Sewerby, Bridlington, which was in the hands of the de Sewerdby family from at least the twelfth century until descendants in a female line sold it in 1545. For two decades the estate passed through several hands before being bought by the Carliell family of Bootham, York. The Carliells moved to Sewerby and the four daughters of the first owner, John Carliell, intermarried with local gentry. His son, Tristram Carliell succeeded to the estates in 1579 and upon his death in 1618 he was succeeded by his son, Randolph or Randle Carliell. He died in 1659 and was succeeded by his son, Robert Carliell, who was married to Anne Vickerman, daughter and heiress of Henry Vickerman of Fraisthorpe. Robert Carliell died in in 1685 and his son Henry Carliell was the last male member of the family to live at Sewerby, dying in 1701 (Johnson, Sewerby Hall and Park, pp.4-9). Around 1714 Henry Carliell's heir sold the Sewerby estate to tenants, John and Mary Greame. The Greame family had originated in Scotland before moving south and establishing themselves in and around Bridlington. One line of the family were yeoman farmers in Sewerby, but John Greame's direct family were mariners and merchants in Bridlington. John Greame (b.1664) made two good marriages; first, to Grace Kitchingham, the daughter of a Leeds merchant of some wealth and, second to Mary Taylor of Towthorpe, a co-heiress. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The constitution and the clergy op Beverley minster in the middle ages McDermid, R. T. W. How to cite: McDermid, R. T. W. (1980) The constitution and the clergy op Beverley minster in the middle ages, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7616/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk II BEVERIEY MINSTER FROM THE SOUTH Three main phases of building are visible: from the East End up to, and including, the main transepts, thirteenth century (commenced c.1230); the nave, fourteenth century (commenced 1308); the West Front, first half of the fifteenth century. The whole was thus complete by 1450. iPBE CONSTIOOTION AED THE CLERGY OP BEVERLEY MINSTER IN THE MIDDLE AGES. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pubHshed without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Papers of Colonel Rupert Alec-Smith and Family of Winestead Page 1 of 53

Hull History Centre: Papers of Colonel Rupert Alec-Smith and Family of Winestead U DAS Papers of Colonel Rupert Alec-Smith 14th cent.-1983 and Family of Winestead Accession number: 1977/07; 2005/16; 2012/27 Biographical Background: Rupert Alexander Alec-Smith was born at Elloughton, near Kingston upon Hull, in 1913. He was the grandson of Alexander Smith, a founding partner of Horsley Smith and Company, a timber importing firm whose small collection of papers dating from 1864 to 1968 is also held at the Hull University Archives (U DHS; see separate entry). Rupert Alec-Smith's parents were Alexander Alec-Smith and Adelaide Horsley. Rupert Alec-Smith was a man with an abiding interest in local and family history and he spent his life fighting to preserve both. In 1936, the demolition of the Georgian Red Hall in Winestead (originally built by the Hildyard family) left a profound impression on him and he founded the Georgian Society for East Yorkshire in 1937 (papers for Lord Derwent and the society are at U DAS/24/13; see also U DX99). He served with the Green Howards during the war and was in Cyprus and the Middle East making the rank of lieutenant colonel by 1944. On leave during the war he rescued fittings from the Georgian residences of Hull's old High Street as this was almost entirely destroyed by German bombs. After the war the Council showed no desire to restore what was left and Alec-Smith continued to salvage what he could from buildings as they were demolished (The Georgian Society for East Yorkshire).