Unclassified DSTI/ICCP(2002)6/FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Digital Infrastructure Overcoming the Digital Divide in China and the European Union

Digital Infrastructure Overcoming the digital divide in China and the European Union Shenglin Ben Romain Bosc Jinpu Jiao Wenwei Li Felice Simonelli Ruidong Zhang Digital Infrastructure Overcoming the digital divide in China and the European Union Shenglin Ben Zhejiang University, CIFI Romain Bosc CEPS Jinpu Jiao Zhejiang University, CIFI & Shanghai Gold Exchange Wenwei Li Zhejiang University, CIFI Felice Simonelli CEPS Ruidong Zhang Zhejiang University, CIFI Supported by Emerging Market Sustainability Dialogues November 2017 The Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) is an independent policy research institute based in Brussels. Its mission is to produce sound policy research leading to constructive solutions to the challenges facing Europe. The views expressed in this book are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed to CEPS or any other institution with which they are associated. ISBN 978-94-6138-646-5 © Copyright 2017, CEPS All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the Centre for European Policy Studies. Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1, B-1000 Brussels Tel: (32.2) 229.39.11 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.ceps.eu Table of Contents Preface ...................................................................................................................................................... i Executive -

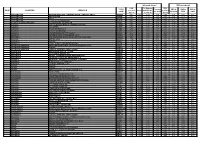

ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR TADIG CODE Calls

Calls made abroad SMS sent abroad Calls To Belgium SMS TADIG To zones SMS to SMS to SMS to ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR received Local and Europe received CODE 2,3 and 4 Belgium EUR ROW abroad (= zone1) abroad 3 AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS COMMUNICATION COMPANY 'AWCC' AFGAW 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN AREEBA MTN AFGAR 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN TDCA AFGTD 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT AFGHANISTAN AFGEA 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 1 ALANDS ISLANDS (FINLAND) ALANDS MOBILTELEFON AB FINAM 0,08 0,29 0,29 2,07 0,00 0,09 0,09 0,54 2 ALBANIA AMC (ALBANIAN MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS) ALBAM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA VODAFONE ALBVF 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA EAGLE MOBILE SH.A ALBEM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA DJEZZY (ORASCOM) DZAOT 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA ATM (MOBILIS) (EX-PTT Algeria) DZAA1 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA WATANIYA TELECOM ALGERIE S.P.A. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

LE 19Ème CONGRÈS DU PARTI COMMUNISTE CHINOIS

PROGRAMME ASIE LE 19ème CONGRÈS DU PARTI COMMUNISTE CHINOIS : CLÔTURE SUR L’ANCIEN RÉGIME ET OUVERTURE DE LA CHINE DE XI JINPING Par Alex PAYETTE STAGIAIRE POSTDOCTORAL POUR LE CONSEIL CANADIEN DE RECHERCHES EN SCIENCES HUMAINES CHERCHEUR À L’IRIS JUIN 2017 ASIA FOCUS #46 l’IRIS ASIA FOCUS #46 - PROGRAMME ASIE / Octobre 2017 e 19e Congrès qui s’ouvrira en octobre prochain, soit quelques semaines avant la visite de Donald Trump en Chine, promet de consolider la position de Xi Jinping dans l’arène politique. Travaillant d’arrache-pied depuis 2013 à se débarrasser L principalement des alliés de Jiang Zemin, l’alliance Xi-Wang a enfin réussi à purger le Parti-État afin de positionner ses alliés. Ce faisant, la transition qui aura vraiment lieu cet automne n’est pas la transition Hu Jintao- Xi Jinping, celle-ci date déjà de 2012. La transition de 2017 est celle de la Chine des années 1990 à la Chine des années 2010, soitde la Chine de Jiang Zemin à celle de Xi Jinping. Ce sera également le début de l’ère des enfants de la révolution culturelle, des « zhiqing » [知青] (jeunesses envoyées en campagne), qui formeront une majorité au sein du Politburo et qui remanieront la Chine à leur manière. Avec les départs annoncés, Xi pourra enfin former son « bandi » [班底] – garde rapprochée – au sein du Politburo et effectivement mettre en place un agenda de politiques et non pas simplement des mesures visant à faire le ménage au cœur du Parti-État. Des 24 individus restants, entre 12 et 16 devront partir; 121 sièges (si l’on compte le siège rendu vacant de Sun Zhengcai) et 16 si Xi Jinping décide d’appliquer plus « sévèrement » la limite d’âge maintenant à 68 ans. -

China Mobile (Hong Kong) Limited

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 20-F ® © REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ®X© ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Ñscal year ended December 31, 2000 OR ® © TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission Ñle number 1-14696 China Mobile (Hong Kong) Limited (Exact Name of Registrant as SpeciÑed in Its Charter) N/A (Translation of Registrant's Name into English) Hong Kong, China (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) 60th Floor, The Center 99 Queen's Road Central Hong Kong, China (Address of Principal Executive OÇces) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Ordinary shares, par value HK$0.10 per share New York Stock Exchange, Inc.* * Not for trading, but only in connection with the listing on the New York Stock Exchange, Inc. of American depositary shares representing the ordinary shares. Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer's classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. As of December 31, 2000, 18,605,312,241 ordinary shares, par value HK$0.10 per share, were issued and outstanding. -

Exploring China's Audience Costs: an Institutionalist Perspective

Exploring China's Audience Costs: An Institutionalist Perspective ∗ Hans H. Tung y This Version: October, 2011 Abstract The recent burgeoning literature of the political economy of dictatorships (Wintrobe, 1998; Bueno de Mesquita et al., 2003; Acemoglu and Robinson, 2006; Gandhi, 2008 ) have made inroads into cracking open the black box of economic policymaking in autocracies, and bringing more insights to the study of non-democratic regimes that used to be dominated by the old totalitarianism paradigm. (Arendt, 1951; Friedrich and Brzezinski, 1965) In the field of international political economy, researchers also start debunking the age-old myth that autocratic leaders are not held accountable domestically. (Weeks, 2008) Along this line of thought, this paper tries to flesh out the argument of autocratic audience costs in the context of a dictatorship, China, that is not only large in size, but also plays a dominant role in all aspects of international political economy. The paper offers an analysis of the political dynamics within the Central Committee of China's Communist Party. It identifies, on the one hand, the key mechanism for the Chinese leadership to be held accountable to its constituent within the Party, and that for it to solicit policy coordination among political elite on the other. Specifying these parameters and their relationship in the model allows us to understand the audience costs the Chinese leadership has to face in the context inter- national policy cooperation. More critically, as far as global governance is concerned, this analysis also makes it possible to assess how credible China's promises to the international community are. -

Roaming User Guide

Data Roaming Tips Singtel helps you stay seamlessly connected with data roaming overseas while avoiding bill shock from unexpected roaming charges. The information below can help you make smart data roaming decisions, allowing you to enjoy your trip with peace of mind. 1. Preferred Network Operators and LTE Roaming ...................................................................................... 2 2. USA Data Roaming Plan Coverage .......................................................................................................... 13 3. Network Lock .............................................................................................................................................. 14 4. My Roaming Settings................................................................................................................................. 16 5. Data Roaming User Guide ......................................................................................................................... 16 1. Preferred Network Operators and LTE Roaming The following table lists our preferred operators offering Singtel data roaming plans and indicates their handset display names. Country Roaming Plans Operator Handset Display Albania Daily Vodafone (LTE) VODAFONE AL / voda AL / AL-02 / 276-02 Anguilla Daily Cable & Wireless C&W / 365 840 Antigua and Daily Cable & Wireless C&W / 344 920 Barbuda CLARO Argentina / CTIARG / AR310 / Claro (LTE) Claro AR Argentina Daily Telefonica (LTE) AR 07 / 722 07 / unifon / movistar Armenia Daily VEON (LTE) -

Roots of Tomorrow's Digital Divide: Documenting Computer Use And

China & World Economy / 61–79, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2013 61 Roots of Tomorrow’s Digital Divide: Documenting Computer Use and Internet Access in China’s Elementary Schools Today Yihua Yang,a Xiao Hu,b Qinghe Qu,b Fang Lai,c, d Yaojiang Shi,e, * Matthew Boswell,c Scott Rozellec Abstract This paper explores China’s digital divide, with a focus on differences in access to computers, learning software, and the Internet at school and at home among different groups of elementary school children in China. The digital divide is examined in four different dimensions: (i) between students in urban public schools and students in rural public schools; (ii) between students in rural public schools and students in private migrant schools; (iii) between migrant students in urban public schools and migrant students in private migrant schools; and (iv) between students in Han-dominated rural areas and students in areas inhabited by ethnic minorities. Using data from a set of large-scale surveys in schools in different parts of the country, we find a wide gap between computer and Internet access of students in rural areas and those in urban public schools. The gap widens further when comparing urban students to students from minority areas. The divide is also large between urban and rural schools when examining the quality of computer instruction and access to learning software. Migration does not appear to eliminate the digital divide, unless migrant families are able to enroll their children in urban public schools. The digital divide in elementary schools may have implications for future employment, education and income inequality in China. -

Internet Diffusion and Digital Divide in China: Some Empirical Results Wei Ge University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee

Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) Americas Conference on Information Systems AMCIS 2003 Proceedings (AMCIS) December 2003 Internet Diffusion and Digital Divide in China: Some Empirical Results Wei Ge University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee Hemant Jain University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: http://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2003 Recommended Citation Ge, Wei and Jain, Hemant, "Internet Diffusion and Digital Divide in China: Some Empirical Results" (2003). AMCIS 2003 Proceedings. 135. http://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2003/135 This material is brought to you by the Americas Conference on Information Systems (AMCIS) at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in AMCIS 2003 Proceedings by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERNET DIFFUSION AND DIGITAL DIVIDE IN CHINA: SOME EMPIRICAL RESULTS Wei Ge Hemant Jain School of Business Administration School of Business Administration University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee [email protected] [email protected] Abstract The paper presents some empirical results of Information & Communication Technology diffusion within China and across countries in Asia. The paper finds that China and most developing countries in Asia are bypassing fixed-line telephone infrastructure by adopting wireless technology. The results also show that the market potentials of mobile phones are greater than fixed-line telephones in these developing countries. Keywords: Internet, diffusion, China, bass diffusion model Introduction Over the past decade, a rapid development has taken place in the field of information and communication technologies1 (ICTs). Recent technological advances in the Internet and the World Wide Web (WWW) have opened up a new digital world. -

China & Technical Global Internet Governance: from Norm-Taker to Norm-Maker?

China & Technical Global Internet Governance: From Norm-Taker to Norm-Maker? by Tristan Galloway L.L.B(Hons)/B.A.(Hons) Deakin University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Deakin University July, 2015 Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to Prof Baogang He, my principal supervisor, for his excellent advice and tireless support, without which the completion of this dissertation would have been impossible. I would also like to express my thanks to my associate supervisors, Prof Wanlei Zhou and Dr Xiangshu Fang, for their advice and support, and to other staff at Deakin University that have provided me with feedback, including but not limited to Dr Chengxin Pan and Dr David Hundt. I am grateful for the further feedback or insight received on elements of my dissertation by numerous academics at academic conferences, seminars and through academic journal peer review processes. I thank the staff and reviewers at China: An International Journal, for their feedback and advice on the joint article submitted by Prof Baogang He and myself that was published in late 2014; while the content and research of the dissertation’s chapters 7 & 8 are primarily attributable to the author, their quality has been improved by this feedback and through collaboration between myself and Prof Baogang He. Elements of the research in these two chapters, and elements of the dissertation’s arguments related to its theoretical perspective, have also been informed by the author’s Honours thesis, submitted to Deakin University in 2010. A professional editing service, The Expert Editor, provided copyediting and proofreading services for the dissertation, according to the guidelines laid out in the university-endorsed national ‘Guidelines for Editing Research Theses’. -

Review of the Development and Reform of the Telecommunications Sector in China”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No

Please cite this paper as: OECD (2003-03-13), “Review of the Development and Reform of the Telecommunications Sector in China”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 69, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/233204728762 OECD Digital Economy Papers No. 69 Review of the Development and Reform of the Telecommunications Sector in China OECD Unclassified DSTI/ICCP(2002)6/FINAL Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 13-Mar-2003 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English text only DIRECTORATE FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INDUSTRY COMMITTEE FOR INFORMATION, COMPUTER AND COMMUNICATIONS POLICY Unclassified DSTI/ICCP(2002)6/FINAL REVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT AND REFORM OF THE TELECOMMUNICATIONS SECTOR IN CHINA text only English JT00140818 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format DSTI/ICCP(2002)6/FINAL FOREWORD The purpose of this report is to provide an overview of telecommunications development in China and to examine telecommunication policy developments and reform. The initial draft was examined by the Committee for Information, Computer and Communications Policy in March 2002. The report benefited from discussions with officials of the Chinese Ministry of Information Industry and several telecommunication service providers. The report was prepared by the Korea Information Society Development Institute (KISDI) under the direction of Dr. Inuk Chung. Mr. Dimitri Ypsilanti from the OECD Secretariat participated in the project. The report benefited from funding provided mainly by the Swedish government. KISDI also helped in the financing of the report. The report is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD.