HKT's Proposed Acquisition Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Opening China's Telecommunications

Research Assessment Exercise 2020 Impact Case Study University: The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology Unit of Assessment (UoA): 22-Business Title of case study: Opening China’s Telecommunications Market for Hong Kong Investors 1. Summary of the impact Policies for the telecommunications sector within the significant Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) cross-border trade agreement between Hong Kong and mainland China have been influenced by research by Xu Yan, linked to his earlier studies on telecommunications policy in Hong Kong and mainland China carried out at HKUST. Such work has had impact on policy by informing senior government policymakers locally and nationally through recommendations on how to liberalize the Chinese telecommunications market under CEPA, and contributed to economic impact following the opening up of this sector to Hong Kong investors under the agreement, mainly in value-added services and particularly in Guangdong Province. 2. Underpinning research Professor of Information Systems, Business Statistics and Operations Management Xu Yan (joined HKUST in 1997) has established himself as an expert on the telecommunications sector and its regulation in Hong Kong and mainland China through a series of published comparative studies that address telecommunication policy issues, in particular market liberalization. Xu’s distinctive perspective on this area draws on his in-depth east-west knowledge resulting from previous working experience in the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications of China and its affiliated university, doctoral studies on telecommunications policy in the UK, and a dedicated research focus on telecommunications market over the past 15 years, with almost all of his publications up to 2015 centered on this area and related issues. -

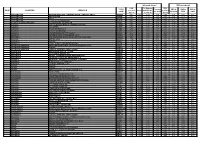

ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR TADIG CODE Calls

Calls made abroad SMS sent abroad Calls To Belgium SMS TADIG To zones SMS to SMS to SMS to ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR received Local and Europe received CODE 2,3 and 4 Belgium EUR ROW abroad (= zone1) abroad 3 AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS COMMUNICATION COMPANY 'AWCC' AFGAW 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN AREEBA MTN AFGAR 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN TDCA AFGTD 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT AFGHANISTAN AFGEA 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 1 ALANDS ISLANDS (FINLAND) ALANDS MOBILTELEFON AB FINAM 0,08 0,29 0,29 2,07 0,00 0,09 0,09 0,54 2 ALBANIA AMC (ALBANIAN MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS) ALBAM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA VODAFONE ALBVF 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA EAGLE MOBILE SH.A ALBEM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA DJEZZY (ORASCOM) DZAOT 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA ATM (MOBILIS) (EX-PTT Algeria) DZAA1 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA WATANIYA TELECOM ALGERIE S.P.A. -

China Mobile (Hong Kong) Limited

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 20-F ® © REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ®X© ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Ñscal year ended December 31, 2000 OR ® © TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission Ñle number 1-14696 China Mobile (Hong Kong) Limited (Exact Name of Registrant as SpeciÑed in Its Charter) N/A (Translation of Registrant's Name into English) Hong Kong, China (Jurisdiction of Incorporation or Organization) 60th Floor, The Center 99 Queen's Road Central Hong Kong, China (Address of Principal Executive OÇces) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Ordinary shares, par value HK$0.10 per share New York Stock Exchange, Inc.* * Not for trading, but only in connection with the listing on the New York Stock Exchange, Inc. of American depositary shares representing the ordinary shares. Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer's classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. As of December 31, 2000, 18,605,312,241 ordinary shares, par value HK$0.10 per share, were issued and outstanding. -

Roaming User Guide

Data Roaming Tips Singtel helps you stay seamlessly connected with data roaming overseas while avoiding bill shock from unexpected roaming charges. The information below can help you make smart data roaming decisions, allowing you to enjoy your trip with peace of mind. 1. Preferred Network Operators and LTE Roaming ...................................................................................... 2 2. USA Data Roaming Plan Coverage .......................................................................................................... 13 3. Network Lock .............................................................................................................................................. 14 4. My Roaming Settings................................................................................................................................. 16 5. Data Roaming User Guide ......................................................................................................................... 16 1. Preferred Network Operators and LTE Roaming The following table lists our preferred operators offering Singtel data roaming plans and indicates their handset display names. Country Roaming Plans Operator Handset Display Albania Daily Vodafone (LTE) VODAFONE AL / voda AL / AL-02 / 276-02 Anguilla Daily Cable & Wireless C&W / 365 840 Antigua and Daily Cable & Wireless C&W / 344 920 Barbuda CLARO Argentina / CTIARG / AR310 / Claro (LTE) Claro AR Argentina Daily Telefonica (LTE) AR 07 / 722 07 / unifon / movistar Armenia Daily VEON (LTE) -

Review of the Development and Reform of the Telecommunications Sector in China”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No

Please cite this paper as: OECD (2003-03-13), “Review of the Development and Reform of the Telecommunications Sector in China”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 69, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/233204728762 OECD Digital Economy Papers No. 69 Review of the Development and Reform of the Telecommunications Sector in China OECD Unclassified DSTI/ICCP(2002)6/FINAL Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 13-Mar-2003 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English text only DIRECTORATE FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INDUSTRY COMMITTEE FOR INFORMATION, COMPUTER AND COMMUNICATIONS POLICY Unclassified DSTI/ICCP(2002)6/FINAL REVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT AND REFORM OF THE TELECOMMUNICATIONS SECTOR IN CHINA text only English JT00140818 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format DSTI/ICCP(2002)6/FINAL FOREWORD The purpose of this report is to provide an overview of telecommunications development in China and to examine telecommunication policy developments and reform. The initial draft was examined by the Committee for Information, Computer and Communications Policy in March 2002. The report benefited from discussions with officials of the Chinese Ministry of Information Industry and several telecommunication service providers. The report was prepared by the Korea Information Society Development Institute (KISDI) under the direction of Dr. Inuk Chung. Mr. Dimitri Ypsilanti from the OECD Secretariat participated in the project. The report benefited from funding provided mainly by the Swedish government. KISDI also helped in the financing of the report. The report is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. -

Virgin Media Consolidated Financial Statements

Consolidated Financial Statements December 31, 2018 VIRGIN MEDIA INC. 1550 Wewatta Street, Suite 1000 Denver, Colorado 80202 United States VIRGIN MEDIA INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Number Part I: Forward-looking Statements...................................................................................................................................... I - 1 Business ..................................................................................................................................................................... I - 3 Management............................................................................................................................................................... I - 21 Principal Shareholder................................................................................................................................................. I - 23 Risk Factors ............................................................................................................................................................... I - 24 Part II: Independent Auditors’ Report.................................................................................................................................... II - 1 Consolidated Balance Sheets as of December 31, 2018 and 2017 ............................................................................ II - 3 Consolidated Statements of Operations for the Years Ended December 31, 2018, 2017 and 2016 .......................... II - 5 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive -

CSL Acquisition FCF Accretive: Prefer HKT Among HK Telcos

March 11, 2014 Hong Kong: Telecom Services Equity Research CSL acquisition FCF accretive: Prefer HKT among HK telcos HKT’s pending acquisition of CSL signals industry consolidation The HK mobile industry stands to benefit from HKT’s proposed US$2.4bn HONG KONG TELECOM VALUATION COMPS acquisition of CSL in the longer term, in our view, as it would reduce 12-Mo. Market Up/Down Total Name Ticker Rating Tgt Px Price Side Return competitive intensity in Asia’s highest penetrated mobile market. The deal PCCW 0008.HK Neutral 3.60 3.75 -4% 2% HKT Trust 6823.HK Neutral 8.90 8.25 8% 14% is pending regulatory approval after receiving PCCW and HKT HTHK 0215.HK Neutral 2.60 2.61 0% 4% SmarTone 0315.HK Neutral 10.00 9.20 9% 12% shareholders’ approval (99.98%) at the EGM on Feb 28. The acquisition P/E EV/EBITDA Div Yld could also potentially remove the overhang of the upcoming spectrum re- Name 2014E 2015E 2014E 2015E 2014E 2015E PCCW 13.0x 11.5x 5.6x 5.2x 6.0% 6.8% auction, which we would see as an industry-wide positive. HKT HKT Trust 22.7x 16.5x 8.9x 8.5x 5.9% 6.0% HTHK 15.6x 15.6x 6.4x 6.3x 4.8% 4.8% management estimates 10%-15% opex synergy on the combined mobile SmarTone 15.8x 16.3x 4.5x 4.5x 3.8% 3.7% business after full integration, or US$596mn-934mn in savings by our ROE ROIC CROCI Name 2014E 2015E 2014E 2015E 2014E 2015E estimate, which we believe is achievable for an in-market consolidation. -

HKT Trust HKT Limited

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. HKT Trust (a trust constituted on November 7, 2011 under the laws of Hong Kong and managed by HKT Management Limited) and HKT Limited (incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 6823) CONTINUING CONNECTED TRANSACTIONS WITH THE PCCW GROUP The HKT Limited Group entered into various transactions with the PCCW Group for operational needs as described in the Prospectus which constituted continuing connected transactions of the Company under the Listing Rules. Such transactions and their respective annual caps will expire on December 31, 2013. It is anticipated that the existing continuing connected transactions with the PCCW Group will continue beyond December 31, 2013. The Directors propose to renew these continuing connected transactions and enter into new continuing connected transaction and set new Annual Caps as described in this announcement for the three financial years ending December 31, 2014 to 2016. PCCW is the controlling holder of the Share Stapled Units. Accordingly, the PCCW Group is a connected person of the Company under the Listing Rules. As the applicable percentage ratios (as defined in the Listing Rules) in respect of the relevant Annual Caps, in each case (or on an aggregated basis, as described below), of the continuing connected transactions, which are categorised according to the providers of the relevant service, exceed 0.1% but are less than 5%, the continuing connected transactions are subject to the reporting and announcement requirements under Rules 14A.45 to 14A.47 of the Listing Rules, but are exempt from the independent shareholders’ approval requirement under Rule 14A.34 of the Listing Rules. -

HUAWEI Smartcare®

White Paper AIOps – Automated Dissatisfied CX Analysis May 2019 Mark Geere, Jing Hao, Chiu-Chung Yue, Derek Chen HUAWEI SmartCare® HUAWEI TECHNOLOGIES CO., LTD. Copyright © Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. 2019. All rights reserved 1. Executive Summary Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning has spread to all industries and all parts of those industries. Whether we are talking about Enterprise adaption within the Automated Cars, the Health industries etc. or within the consumer world where it is now embedded within everyone’s phones to help them take a better picture or more efficiently use their battery power. The point is that AI is now ubiquitous throughout our lives at work, home and within the products and services we consume. So it is no surprise that the Telecoms industry is also looking at how they can use AI to (1) improve internal efficiencies across their organizations, as well as (2) drive better customer engagement to enhance customer experience on the services they deliver (Figure 1). The “Automated Dissatisfied CX Analysis” use case is a part of the AIOps catalyst which links Hong Kong Telecom (HKT) with Huawei’s SmartCare® Customer experience solution to deliver on these 2 key areas. The focus of the use case is to investigate how customer complaints at the point of reporting can be intelligently analyzed in order to deliver the following benefits: Support network optimization: By aggregating affected users and problem dimensions, this use case supports network problem optimization based on user experience assurance and improves O&M efficiency. Support proactive care: Provides proactive care for identified affected users to improve customer satisfaction. -

Views and Comments on the Proposal

Telecommunications Regulatory Affairs Advisory Committee Minutes of the Eighteenth Meeting Held on Thursday, 27 November 2019 at 2:30 p.m. in OFCA Conference Room, 20/F Wu Chung House Members Present Mr Sanda Cheuk Office of the Communications Authority (OFCA) (Chairman) Miss Elaine Hui OFCA (Secretary) Mr Alex Wong Communications Association of Hong Kong Ir John Chan The Hong Kong Institution of Engineers Mr Ben Li The Institution of Engineering and Technology Hong Kong Ms Agnes Tan Hong Kong Broadband Network Limited / HKBN Enterprise Solutions Limited / HKBN Enterprise Solutions HK Limited (HKBN) Ms Sarah Hui China Mobile Hong Kong Company Limited (CMHK) Mr Kevin Chu Hong Kong Telecommunications (HKT) Limited, PCCW-HKT Telephone Limited and Hong Kong Telecommunications (HKT) Limited and PCCW Global (HK) Limited Miss Katherine Kwok HGC Global Communications Limited Ms Juliana Wong Hutchison Telephone Company Limited and Genius Brand Limited Mr T L Or SmarTone Mobile Communications Limited and SmarTone Communications Limited (SmarTone) Mr Karson Ng China Telecom Global Limited Mr Kenneth Kwok ComNet Telecom (HK) Limited Mr J Law Easy Tone Network Limited (Easy Tone) Mr Larry Lee Hong Kong Cable Television Limited 1 Mr Donald Chan NTT Com Asia Limited (NTT) Mr Walter Ngan Towngas Telecommunications Fixed Network Limited Mr Eric Cheung TraxComm Limited Mr Allen Law Village Telephone Limited Mr Y T Kan Hong Kong Police Force (HKPF) Dr Patrick Tsie Ad personam In Attendance Mr Malcolm Leong HKBN Mr Mike Pan CMHK Mr Eric Lee SmarTone Mr Alan -

Pay-Per-Use Roaming Rates

Pay-Per-Use Roaming Rates Kindly select a destination below to view the rates. Afghanistan Armenia Azerbaijan Bahrain Bangladesh Bhutan Brunei Cambodia China Georgia Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan Kazakhstan Asia Kyrgyzstan Laos Macau Malaysia Maldives Mongolia Myanmar Nepal Pakistan Philippines South Korea Sri Lanka Taiwan Tajikistan Thailand Timor-Leste Turkmenistan Uzbekistan Vietnam Anguilla Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Aruba Bahamas Barbados Belize Bermuda Bolivia Bonaire Brazil British Virgin Islands Canada Cayman Islands Chile Colombia Costa Rica Cuba Curacao Dominica Dominican Republic Ecuador El Salvador French Guiana French West Indies Haiti Grenada Americas Guadeloupe Guatemala Guyana Honduras Jamaica Martinique Mexico Montserrat Nicaragua Orkney Islands Panama Paraguay Peru Puerto Rico Shetland St. Kitts and Nevis St. Lucia St. Martin St. Vincent and The Grenadines Suriname Trinidad and Tobago Turks and Caicos US Virgin Islands USA Uruguay Venezuela Aland Albania Andorra Austria Azores Belarus Belgium Bornholm Bosnia and Herzegovina Bulgaria Ceuta Channel Islands Corsica (Corse) Crete (Kriti) Croatia Cyclades Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Estonia Faroe Islands Finland Formentera France Germany Gibraltar Gotland Greece Guernsey Hungary Ibiza (Evissa) Iceland Ionian Islands Ireland Isle of Man Italy Jersey Europe Kosovo Latvia Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Macedonia Madeira Mallorca Malta Melilla -

Network List Addendum

Network List Addendum IN-SITU PROVIDED SIM CELLULAR NETWORK COVERAGE COUNTRY NETWORK 2G 3G LTE-M NB-IOT COUNTRY NETWORK 2G 3G LTE-M NB-IOT (VULINK, (TUBE, (VULINK) (VULINK) TUBE, WEBCOMM) (VULINK, (TUBE, (VULINK) (VULINK) WEBCOMM) TUBE, WEBCOMM) WEBCOMM) Benin Moov X X Afghanistan TDCA (Roshan) X X Bermuda ONE X X Afghanistan MTN X X Bolivia Viva X X Afghanistan Etisalat X X Bolivia Tigo X X Albania Vodafone X X X Bonaire / Sint Eustatius / Saba Albania Eagle Mobile X X / Curacao / Saint Digicel X X Algeria ATM Mobilis X X X Martin (French part) Algeria Ooredoo X X Bonaire / Sint Mobiland Andorra X X Eustatius / Saba (Andorra) / Curacao / Saint TelCell SX X Angola Unitel X X Martin (French part) Anguilla FLOW X X Bosnia and BH Mobile X X Anguilla Digicel X Herzegovina Antigua and Bosnia and FLOW X X HT-ERONET X X Barbuda Herzegovina Antigua and Bosnia and Digicel X mtel X Barbuda Herzegovina Argentina Claro X X Botswana MTN X X Argentina Personal X X Botswana Orange X X Argentina Movistar X X Brazil TIM X X Armenia Beeline X X Brazil Vivo X X X X Armenia Ucom X X Brazil Claro X X X Aruba Digicel X X British Virgin FLOW X X Islands Australia Optus X CCT - Carribean Australia Telstra X X British Virgin Cellular X X Islands Australia Vodafone X X Telephone Austria A1 X X Brunei UNN X X Darussalam Austria T-Mobile X X X Bulgaria A1 X X X X Austria H3G X X Bulgaria Telenor X X Azerbaijan Azercell X X Bulgaria Vivacom X X Azerbaijan Bakcell X X Burkina Faso Orange X X Bahamas BTC X X Burundi Smart Mobile X X Bahamas Aliv X Cabo Verde CVMOVEL