Winter 2019 Director’S Column

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Festival Brochure

Celebrating the Blues 2 days featuring 8 more days featuring Plus: healdsburgjazz.org AN EVENING OF JAZZ ON FILM WITH ARCHIVIST MARK CANTOR Co-Produced by Healdsburg Jazz and Smith Rafael Film Center SUNDAY, MAY 18 • SMITH RAFAEL FILM CENTER 1118 Fourth Street, San Rafael 6PM FILM AND Q&A 8PM Wine and Music Reception with PIANO JAZZ by KEN COOK Ticket Cost: Discount for current members of CFI and Healdsburg Membership Card required Film & Q&A: $15/$12 for members Film, Q&A and Reception: $25/$20 members Advance tickets online at cafilm.org or at the Rafael Box Office Film archivist extraordinaire Mark Cantor returns this year for a Healdsburg Jazz Festival tune-up,“Jazz Night at the Movies” at the Smith Rafael Film Theater in San Rafael. There could be no better way for festival goers seeking a little (or a lot) of history about the great American art form Healdsburg Jazz presents every year than by attending a screening by Mark. His collection of jazz film clips is over 4,000 strong, including all the greats from most genres of jazz, blues and jazz dance: Dizzy, Tatum, Ella, Bird, Trane, Satchmo, Billie— you name it. Mark will have words to say about each of the clips he screens, and afterward viewers are invited to chat with him during a music and wine reception with Ken Cook on piano. Ticket sales and seat reservations secured by credit card available by phone only. Adults $25, must be accompanied by a child. Student seats must be reserved by credit card. -

Ben Harper and Charlie Musselwhite Nightclub

Ben Harper And Charlie Musselwhite Nightclub Posts about Carole King written by thedailyrecord. Mostrando entradas con la etiqueta Ben Harper. “It was heartwarming, because there’s a genuine affection for the Belly Up and the artists are able to support the club with these albums. Bobby Johnson - Get Up and Dance (2013) Funk, R&B, Soul | 320 kbps | MP3 | 148. We were so pleased to recieve the message that […] Do you like it? 16. Their first album, 2012’s Get Up! , spurred, at least in my mind at the time, comparisons to other blues and jazz artists such as John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters. It’s the coolest makeover on the record, enigmatic and slinky as its originator. El llegendari músic va pensar que tots dos havien de tocar junts. Su destino Hamburgo, donde todavía vive con ochentaytantos años. Protoje, 9 p. 15 Dec 2019 - New at #TopMusic 7 days (15 Dec): 'The Way It Used To Be' by Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross; 'Nightclub' by Ben Harper & Charlie Musselwhite;. Download Ben Harper With Charlie Musselwhite "Get Up!" Now:iTunes: http://smarturl. Ben Harper & Charlie Musselwhite "When I Go": When I leave here I'll have no place to go And it's much too late to change my name I'm gonna take y. 08/03/2018 - Ben Harper & Charlie Musselwhite @ The Gothic Theatre - Englewood, CO Ben Harper & Charlie Musselwhite played the Gothic Theatre off Broadway to a sold out crowd last night. Get Up! is an album by the American musicians Charlie Musselwhite and Ben Harper , their twenty-ninth and eleventh album, respectively. -

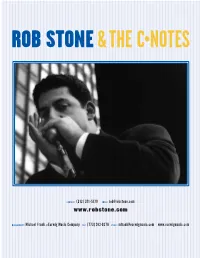

CONTACT: (312) 371 -5179 EMAIL: [email protected]

ROB STONE &THE C•NOTES CONTACT: (312) 371 -5179 EMAIL: [email protected] www.robstone.com MANAGEMENT: Michael Frank AT Earwig Music Company TEL: (773)262-0278 EMAIL: [email protected] www.earwigmusic.com A LIVE PERFORMANCE BY ROB STONE CAN TRANSPORT THE LISTENER BACK TO THE HEYDAY OF CHICAGO BLUES. Fronted by Harp-playing vocalist ROB STONE and held together by a rock-solid rhythm section, the group is comprised of seasoned professionals with well over half a century of combined blues playing experience. They’ve paid their dues in the smoky Chicago blues joints and toured coast to coast across North America and Europe, as well as the Hawaiian islands and Japan, playing countless blues festivals, club dates and television appearances. Separately, the members of the group have recorded for the respected Alligator, Evidence, Hightone, Ice House, Marquis, Appaloosa and Magnum blues labels, and received national recognition in countless blues publications. These musicians have performed with and learned from many of the greats...and it shows from the first note. They are all authentic showmen with pure abil- ity to tear up a stage, as evidenced by their prominent role in the recent Martin Scorsese-produced “Godfathers and Sons” episode of The Blues series that aired recently on PBS stations natiowide. Together they now have a brand new release on Chicago’s Earwig label. As a vocalist Rob Stone is powerful, yet relaxed and natural; as a harmonica player he evokes the sounds of greats like Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson and Walter Horton. This band navigates their way effortlessly through one lean arrangement after another, from a soulful slow blues to a ferocious, driving slide guitar workout recalling past greats like Elmore James, Earl Hooker, and Muddy Waters, as well as all the blues harp legends from the hey- day of Chicago blues. -

Band/Surname First Name Title Label No

BAND/SURNAME FIRST NAME TITLE LABEL NO DVD 13 Featuring Lester Butler Hightone 115 2000 Lbs Of Blues Soul Of A Sinner Own Label 162 4 Jacks Deal With It Eller Soul 177 44s Americana Rip Cat 173 67 Purple Fishes 67 Purple Fishes Doghowl 173 Abel Bill One-Man Band Own Label 156 Abrahams Mick Live In Madrid Indigo 118 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues Swallow 033 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues Ace 084 Abshire Nathan Pine Grove Blues/The Good Times Killin' Me Ace 096 Abshire Nathan The Good Times Killin' Me Sonet 044 Ace Black I Am The Boss Card In Your Hand Arhoolie 100 Ace Johnny Memorial Album Ace 063 Aces Aces And Their Guests Storyville 037 Aces Kings Of The Chicago Blues Vol. 1 Vogue 022 Aces Kings Of The Chicago Blues Vol. 1 Vogue 033 Aces No One Rides For Free El Toro 163 Aces The Crawl Own Label 177 Acey Johnny My Home Li-Jan 173 Adams Arthur Stomp The Floor Delta Groove 163 Adams Faye I'm Goin' To Leave You Mr R & B 090 Adams Johnny After All The Good Is Gone Ariola 068 Adams Johnny After Dark Rounder 079/080 Adams Johnny Christmas In New Orleans Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny From The Heart Rounder 068 Adams Johnny Heart & Soul Vampi 145 Adams Johnny Heart And Soul SSS 068 Adams Johnny I Won't Cry Rounder 098 Adams Johnny Room With A View Of The Blues Demon 082 Adams Johnny Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me Rounder 097 Adams Johnny Stand By Me Chelsea 068 Adams Johnny The Many Sides Of Johnny Adams Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny The Sweet Country Voice Of Johnny Adams Hep Me 068 Adams Johnny The Tan Nighinggale Charly 068 Adams Johnny Walking On A Tightrope Rounder 089 Adamz & Hayes Doug & Dan Blues Duo Blue Skunk Music 166 Adderly & Watts Nat & Noble Noble And Nat Kingsnake 093 Adegbalola Gaye Bitter Sweet Blues Alligator 124 Adler Jimmy Midnight Rooster Bonedog 170 Adler Jimmy Swing It Around Bonedog 158 Agee Ray Black Night is Gone Mr. -

The Ultimate Complete Michael Bloomfield Discography

The Ultimate Complete Michael Bloomfield Discography Photo ©: Mike Shea/Patrick Shea Michael Bloomfield December 7, 1964 “The music you listen to becomes the soundtrack of your life....” Michael Bloomfield Feb. 13, 1981 Compiled by René Aagaard, Aalekaeret 13, DK-3450 Alleroed, Denmark – [email protected] www.the-discographer.dk - Copyright September 2015 Version 10 Michael Bernard Bloomfield was born July 28, 1943, in Chicago, Illinois and was found dead in his car in San Francisco, California on February 15, 1981. Between these dates he made a lasting impression on the world of music. Today he is still considered one of the greatest and most influential white guitarists from the USA. He learned by listening to all the great black musicians that played Chicago in the ’50s and early ’60s - people like Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Big Joe Williams, Sleepy John Estes and many more. He was always eager to join them on stage and made quite a name for himself. He also played with many white musicians his own age, like Barry Goldberg, Charlie Musselwhite, Nick Gravenites and whoever toured Chicago. In the early ’60s, barely 20 years old, he was the musical director of a Chicago blues club called The Fickle Pickle. Here he hired many of the old, black blues legends, and he treated them so well that Big Joe Williams even mentions him in a song about the club, “Pick a Pickle”. In 1964 Michael Bloomfield was “discovered” by legendary producer John Hammond, Sr., who went to Chicago to hear and record Bloomfield, and then invited him to New York to audition for Columbia Records. -

ELECTRIC BLUES the DEFINITIVE COLLECTION Ebenfalls Erhältlich Mit Englischen Begleittexten: BCD 16921 CP • BCD 16922 CP • BCD 16923 CP • BCD 16924 CP

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] PLUG IT IN! TURN IT UP! ELECTRICELECTRIC BBLUESLUES DAS STANDARDWERK G Die bislang umfassendste Geschichte des elektrischen Blues auf insgesamt 12 CDs. G Annähernd fünfzehneinhalb Stunden elektrisch verstärkte Bluessounds aus annähernd siebzig Jahren von den Anfängen bis in die Gegenwart. G Zusammengestellt und kommentiert vom anerkannten Bluesexeperten Bill Dahl. G Jede 3-CD-Ausgabe kommt mit einem ca. 160-seitigen Booklet mit Musikerbiografien, Illustrationen und seltenen Fotos. G Die Aufnahmen stammen aus den Archiven der bedeutendsten Plattenfirmen und sind nicht auf den Katalog eines bestimmten Label beschränkt. G VonT-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Ray Charles und Freddie, B.B. und Albert King bis zu Jeff Beck, Fleetwood Mac, Charlie Musselwhite, Ronnie Earl und Stevie Ray Vaughan. INFORMATIONEN Mit insgesamt annähernd dreihundert Einzeltiteln beschreibt der Blueshistoriker und Musikwissenschaftler Bill Dahl aus Chicago die bislang umfassendste Geschichte des elektrischen Blues von seinen Anfängen in den späten 1930er Jahren bis in das aktuelle Jahrtausend. Bevor in den Dreißigerjahren Tonabnehmersysteme, erste primitive Verstärker und Beschallungssysteme und schließ- lich mit Gibsons ES-150 ein elektrisches Gitarren-Serienmodell entwickelt wurde, spielte die erste Generation der Gitarrenpioniere im Blues in den beiden Jahrzehnten vor Ausbruch des Zweiten Weltkriegs auf akustischen Instrumenten. Doch erst mit Hilfe der elektrischen Verstärkung konnten sich Gitarristen und Mundharmonikaspielern gegenüber den Pianisten, Schlagzeugern und Bläsern in ihrer Band behaupten, wenn sie für ihre musikalischen Höhenflüge bei einem Solo abheben wollten. Auf zwölf randvollen CDs, jeweils in einem Dreier-Set in geschmackvollen und vielfach aufklappbaren Digipacks, hat Bill Dahl die wichtigsten und etliche nahezu in Vergessenheit geratene Beispiele für die bedeutendste Epoche in der Geschichte des Blues zusammengestellt. -

Download Promo Pack

John Hammond 2011 BLUES HALL OF FAME Inductee 2012 NEW YORK BLUES HALL OF FAME Inductee 2011 Blues Music Award WINNER for Acoustic Artist of the Year 2010 GRAMMY Nominee for Rough & Tough (Best Traditional Blues Album). Rough & Tough, his 33rd album since his 1962 self-titled debut, was recorded live in November 2008 at St. Peter's Episcopal Church in NYC. Included are classic songs written by Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Blind Willie McTell and Tom Waits among others, as well as two John Hammond originals 1985 GRAMMY Winner for his performance on Blues Explosion, a compilation from the Montreux Jazz Festival also featuring Stevie Ray Vaughan, Koko Taylor and others 2006 GRAMMY Nominee In Your Arms Again 1999 GRAMMY Nominee Long As I Have You 1998 GRAMMY Nominee Found True Love 1994 GRAMMY Nominee Trouble No More 1993 GRAMMY Nominee Got Love If You Want It *Blues Music Award Winner: 2004 & 2003 for Best Acoustic Blues Artist, 2002 for Best Acoustic Album for his Tom Waits produced Wicked Grin. To date John Hammond has been honored with a total "John's sound is so compelling, complete, of 8 Blues Music Awards and an additional 10 nominations symmetrical and soulful with just his voice, guitar *Featured on 2010 Blues Music Awards Nominated Things and harmonica, it is at first impossible to imagine About Comin' My Way - A Tribute to the music of the improving it... He's a great force of nature. John Mississippi Sheiks (Acoustic Album of the Year) sounds like a big train coming. He chops them all *2002 GRAMMY Nominee for Best Historical Album Washington down." Square Memoirs Box Set features John Hammond performing Tom Waits "Drop Down Mama" "John Hammond is a master.. -

Mississippi Musicians Hall of Fame Inductees Blues • Charlie

Mississippi Musicians Hall of Fame Inductees Tammy Wynette - Tremont Mississippi Sheiks - Bolton Blues Charlie Musselwhite - Kosciusko O. B. McClinton - Senatobia Hubert Sumlin - Greenwood Carl Jackson - Louisville Vasti Jackson - McComb Charlie Feathers - Slayden Willie Dixon - Vicksburg Bobbie Gentry - Chickasaw County Robert Johnson - Hazlehurst LeAnn Rimes - Pearl B. B. King - Itta Bena Mickey Gilley – Natchez Charlie Patton - Edwards Muddy Waters - Rolling Fork Gospel and Religious Howlin Wolf - White Station James Blackwood/Blackwood Bros. - Ackerman Sonny Boy Williamson - Glendora Canton Spirituals - Canton Pinetop Perkins - Belzoni Jackson Southernaires - Jackson Mississippi John Hurt - Teoc Mississippi Mass Choir/Frank Williams -Jackson Tommy Johnson - Terry Pop Staples/Staples Singers - Winona Honey Boy Edwards - Shaw C. L. Franklin - Sunflower County Joseph Lee (Big Joe) Williams - Crawford Blind Boys of Mississippi - Piney Woods School Elmore James - Richland Williams Brothers - Smithdale Cleophus Robinson - Canton Classical James Owens - Clarksdale James Sclater - Clinton Southern Sons - Delta John Alexander - Meridian Pilgrim Jubilees - Houston Ruby Pearl Elzy - Pontotoc Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield - Natchez Jazz Samuel Jones - Inverness Brew Moore - Indianola Willard Palmer - McComb Mose Allison - Tippo Leontyne Price - Laurel Milt Hinton - Vicksburg William Grant Still - Woodville Jimmie Lunceford - Fulton Walter Turnbull - Greenville Cassandra Wilson - Jackson Milton -

Past Festival Artists

Poster Gallery You can find us during RBC Bluesfest in the Foyer of the Canadian War Museum. 1 Vimy Pl., Ottawa, ON K1A 0M8 To order a Poster or Catalogue, email us at: [email protected] * Posters can be shipped at an additional cost upon request* Follow us on Twitter @ottawabluesfest Catalogue of Friend us on Facebook at: www.facebook.com/ottawabluesfest Commemorative Posters RBC Bluesfest General Inquiries: Phone: 613-247-1188 Toll-Free: 1-866-258-3478 Fax: 613-247-2220 Includes over 1000 Location: 450 Churchill Ave. N autographed posters signed by Ottawa, ON, Canada K1Z 5E2 Past Festival Artists Official Framing Studio www.germotte.ca All Sales Support Christmas Poster RBC Bluesfest Blues in the Schools Sale RBC Bluesfest Blues in the Schools (BITS) is an inspiring opportunity for students of all ages to draw on the energy and experience of award winning musicians through workshops and hands-on instructional techniques. Can’t find a gift for that hard to shop for person? Engaging over 6,000 Ottawa area students since Is one of your friends an avid music fan? its inception. If yes, then we can help you at the RBC Bluesfest Christmas Poster Sale! December 3 & 4 1PM – 4PM Festival House – 450 Churchill Ave. N All funds from the sale are in support of RBC Bluesfest Blues in the Schools. Not all posters will be available on-site, so we recommend BITS is funded by RBC Bluesfest music patrons and the following partners: you forward your request(s) to – [email protected] before December 3, 2016. -

Curtis Damage

CURTIS SALGADO NEW ALBUM RELEASE DAMAGE CONTROL Order Today Click Here! Four Print Issues Per Year Every January, April, July, and October get the Best In Blues delivered right t0 you door! Artist Features, CD, DVD Reviews & Columns. Award-winning Journalism and Photography! Order Today Click Here! 20-0913-Blues Music Magazine Full Page 4C bleed.indd 1 17/11/2020 09:17 BLUES MUSIC ONLINE FEBRUARY 23, 2021 - Issue 28 Table Of Contents 06 - CURTIS SALGADO The Cream Rises to The Top on Damage Control By Don Wilcock 20 - CD REVIEWS By Various Writers & Editors 36 - BLUES MUSIC STORE Various New & Classic CDs and Vinyl On Sale 45 - BLUES MUSIC SAMPLER CD Sampler 27 - October 2020 - Download 14 Songs COVER PHOTOGRAPHY © JESSICA KEAVENY TOC PHOTOGRAPHY © JESSICA KEAVENY Read The News Click Here! All Blues, All The Time, AND It's FREE! Get Your Paper Here! Read the REAL NEWS you care about: Blues Music News! FEATURING: - Music News - Breaking News - CD Reviews - Music Store Specials - Video Releases - Festivals - Artists Interviews - Blues History - New Music Coming - Artist Profiles - Merchandise - Music Business Updates CURTIS SALGADO The Cream Rises to The Top By Don Wilcock PHOTOGRAPHY © LAURA CARBONE never liked what Bob Dylan was doing because to me if you can’t play harmonica like Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson, James Cotton, Walter Horton, or “IGeorge Smith, man, I’m not interested.” Curtis Salgado’s medical problems including liver cancer, two bouts of lung cancer and quadruple bypass surgery all within an 11-year period may have improved his game just like Dylan’s medical issues did and still do. -

CHARLIE MUSSELWHITE – “I Ain't Lyin' . . .”

CHARLIE MUSSELWHITE – “I Ain’t Lyin’ . .” radio promotion contact: Brad Hunt, The WNS Group (585) 765-2083, [email protected] Charlie’s riveting Sonoma County show brought his unstoppable, hard hitting, tone heavy sound to the audience who couldn’t get enough. Luckily someone had turned on the tape and Charlie knew just what to do – he took the tapes down to Clarksdale MS and delivered them into the capable mixing and mastering hands of Gary Vincent who in collaboration with Charlie, brought Mississippi mud to this exceptional live recording. I AIN’T LYIN’ is all Charlie. The cd is a group of painstakingly crafted original tunes penned by the hand of this Mississippi master that resonate with the land of Mississippi itself. Charlie’s music rises from the river, crosses the levy, dances through the streets and cuts straight to the heart of what it is to be alive. Fifty years of nonstop touring, performing and recording have reaped huge rewards. Charlie Musselwhite is living proof that great music only gets better with age. This man cut his (musical) teeth alongside Muddy Waters, Howling Wolf and everyone on the south side of Chicago in the early 1960’s – thank your lucky stars he is still with us telling the truth with a voice and harp tone like no other. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Charlie Musselwhite may be the only musician to get a huge ovation just for opening his briefcase. Fans know that’s where he keeps his harmonicas and they’re about to hear one of the true masters work his magic on the humble instrument. -

Finding Aid for the Blues Archive Poster Collection (MUM01783)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library April 2020 Finding Aid for the Blues Archive Poster Collection (MUM01783) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Material Culture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Blues Archive Poster Collection (MUM01783), Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding Aid for the Blues Archive Poster Collection MUM01783 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Scope and Content Creator - Collector Arrangement Cole, Dick "Cane"; King, B. B.; Living Blues Administrative Information (Magazine); Malaco Records; University of Mississippi; Miller, Betty V. Related Materials Controlled Access Headings Title Blues Archive Poster Collection Collection Inventory ID Series 1: General Posters MUM01783 Series 2: B. B. King Posters Date [inclusive] 1926-2012 Series 3: Malaco Records Posters Date [bulk] Series 4: Living Blues Bulk, 1970-2012 Posters Extent Series 5: Dick “Cane” 3.0 Poster cases (16 drawers) Cole Collection Location Series 6: Betty V. Miller Blues Archive Collection Series 7: Southern Language of Materials Ontario Blues Association English Broadsides Abstract Series 8: Oversize These blues posters, broadsides, and oversize Periodicals printings, collected by various individuals and Series 9: Blues Bank institutions, document the world of blues advertising.