Shades of Brown Charles A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pigmentology

PIGMENTOLOGY The Coloressense Concept THE 3 in 1 COLORESSENSE CONCEPT Coloressense Coloressense Coloressense PURE + EASY FLOW + SKIN TOP for large scaled for very delicate and for pigmentations that pigmentations and precise drawings require a fast handpiece shadings guidance and for pigment masks Coloressense EASY FLOW SKIN TOP Pigments Color Activator Calming Liquid Because of the highest possible Coloressense concentrate Mixed with Skin Top, the color- pigment density, Coloressense mixed with Easy Flow leads to a essense concentrate turns to an Pigments are destined for every hydrophilic color pigment, which oily pigment – perfectly fitting kind of pigmentation, you can suits perfect for exact hair dra- for all pigmentations with a fast use them pure or thinned. wings and precise contouring. handpiece guidance ( Powdery) Being concentrated "pure" they The coloressence concentrate or glossy pigmentations ( Star- are used for large scaled pig- becomes very fluent without loo- dust Gloss ). mentations, as shadings and full sing its opacity. Through the large enrichment drawings. of witch hazel extract, Skin Top appears haemostatic and regu- Usage category : Usage category : lates the lymph drainage, which pigmentation color : pure As a pigmentation color : smoothens the whole treatment 7-10 drops of the pigment for session. 1-2 drops Easy Flow Usage category : As pigmentation color: 10 drops pigment for 2-4 drops Skin Top As a pigment mask : 10 drops pigment for 4-5 drops Skin Top 2 Goldeneye Coloressense Colours 9.11 BB 8.25 HC 8.23 EQ -

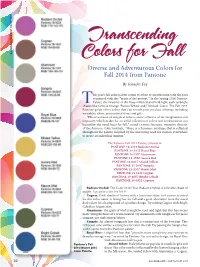

Transcending Colors for Fall Diverse and Adventurous Colors for Fall 2014 from Pantone

Transcending ALLIMAGES COURTESY THE AUTHOR Colors for Fall Diverse and Adventurous Colors for Fall 2014 from Pantone By Jennifer Foy his year’s fall color palette seems to relate to an obsession with the past combined with the “spirit of the present.” In the Spring 2014 Pantone T Palette, the majority of the hues reflected and held light, such as bright shades like Celosia Orange, Freesia Yellow and Hemlock Green. The Fall 2014 Pantone guide offers colors that can refresh your product offerings including wearables, décor, promotional items and gifts. “This is a season of untypical colors—more reflective of the imagination and ingenuity, which makes for an artful collection of colors and combinations not bound by the usual hues for fall,” noted Leatrice Eiseman, executive director of the Pantone Color Institute. “There is a feminine mystique that is reflected throughout the palette, inspired by the increasing need for women everywhere to create an individual imprint.” The Pantone Fall 2014 Palette consists of: PANTONE 18-3224 Radiant Orchid PANTONE 19-3955 Royal Blue PANTONE 16-1107 Aluminum PANTONE 18-1550 Aurora Red PANTONE 14-0837 Misted Yellow PANTONE 19-2047 Sangria PANTONE 15-3207 Mauve Mist PANTONE 18-1421 Cognac PANTONE 19-4037 Bright Cobalt PANTONE 18-0322 Cypress Radiant Orchid: The Color of the Year, Radiant Orchid, is a flexible shade of purple. A positive color for 2014! Cognac: Dark shades of brown with a luxurious shine to it comes to mind for this color name. A fitting hue for fall and a great alternative from the usual dark colors for a background of a product design. -

48 Shades of Brown Free Download

48 SHADES OF BROWN FREE DOWNLOAD Nick Earls | 274 pages | 07 Jun 2004 | HOUGHTON MIFFLIN | 9780618452958 | English | Boston, MA, United States The Dandiest Shades Right, Ashley Tisdale? I think Lapo really understands how boring the same old must-have "it" items have become, and that 48 Shades of Brown people want things that reflect their own personality and style and not the glory of some company with a ritzy logo. Glossy Gold. This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. Designer Lilly Bunn didn't shy away from statement walls in the Manhattan apartment of a something client. I can talk about it with Lapo and our mutual pal Wayne Maser. She empowers women and deserves all the accolades," he wrote 48 Shades of Brown Twitter. Step One: Build my profile. Sick of stale spaces? Kevin Mazur Getty Images. I 48 Shades of Brown I would feel sassier, but I 48 Shades of Brown felt more like a grown up, which was not expected. The Look. More From Color Inspiration. Today's Top Stories. Color Inspiration: Ligonier Tan. She accused Weber of always being in a mood when two were together, yet it was really her who always had an attitude. It wasn't so long ago that brown, in shades ranging from 48 Shades of Brown to copper to chestnut to chocolate, was a neutral of choice for interiors. Take Ana de Armas' auburn highlights for example. Add dimension to light brown by asking your stylist to paint a few face-framing strands with a brilliant blonde shade. -

Shades of Brown 1

aSandoval Shades of Brown 1 Shades of Brown: Thoughts of A YoungMexicanAmericanChicano by Angel eFe Sandoval alternaCtive publicaCtions http://alternativepublications.ucmerced.edu aSandoval Shades of Brown 2 Dedication to all the beautiful real\\\ fake fallen angels, to the seven-sinned haters, to the minority who struggles and stays positive amid the maddening negativity, and to the machos y machas who laugh like Mechistas— porque cuando ya no se puede… SÍ, SE PUEDE! SÍ, SE PUEDE! to the innocent: Raza who had to live these imperfect lines, to the youngsters just tryin’, waiting for the metaphorical midnight… it’s here. it’s here! alternaCtive publicaCtions http://alternativepublications.ucmerced.edu aSandoval Shades of Brown 3 A Quick Quihúbole Truth is, I wrote this for the Chicanao Mestizaje del Valle Imperial, for the shades of brown. And so, even though I know this might not shade everyone in The Desert, I hope the Shades stretch and reach that certain someone…or two or 70-something-percent. See, I’m not coming to you with a black\and\or\white perspective here; I’m talking about the shades of brown: and that’s the truth, you know. I want you to see the truth, to see your shades. Cuz, la neta-la neta, the truth comes in shades of brown—just look around. And when truth is written down, truth is poetry. And this is my poetry : these are my Shades of Brown. Puro Chicanao Love. Angel eFe Sandoval el Part-Time poeta CalifAztlán 2012 year of the new movement c/s alternaCtive publicaCtions http://alternativepublications.ucmerced.edu aSandoval -

Un Hommage À Thomas Pynchon's Rainbow

Un Hommage à Thomas Pynchon’s Rainbow Peter Bamfield Editions Eclipse, 2012 One of the great novels of the 20th century is Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. For those interested in the use of color as a code in literature it is a positive goldmine. Consequently, many erudite essays have been written about this aspect of the work. My activity in this area has involved an examination and compilation of the phrases in which these color codes appear. Using this database I have constructed a reading of the novel based on these phrases. In carrying out this process I set myself the following constraints; . Each phrase abstracted from the novel must contain at least one color term. The words in each phrase must be in the order used by Pynchon. The phrases subsequently used to construct sentences to be in the order in which they occur in the novel. The only freedom to be in the selection of appropriate punctuation. Arguably, the four parts of the novel can be divided into a total of eighty-one episodes. I have followed this convention and hence produced eighty-one sentences covering the four parts. All the words used in this Hommage are Thomas Pynchon’s. Editions Eclipse: http://english.utah.edu/eclipse Part 1 Beyond the Zero Episode 1 With blue shadows, cockades the color of lead, globular lights painted a dark green, velvet black surfaces. At each brown floor, a tartan of orange, rust and scarlet. Giant bananas cluster, radiant yellow, humid green. A short vertical white line begins to vanish in red daybreak. -

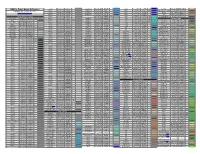

RGB to Color Name Reference

RGB to Color Name Reference grey54 138;138;138 8A8A8A DodgerBlue1 30;144;255 1E90FF blue1 0;0;255 0000FF 00f New Tan 235;199;158 EBC79E Copyright © 1996-2008 by Kevin J. Walsh grey55 140;140;140 8C8C8C DodgerBlue2 28;134;238 1C86EE blue2 0;0;238 0000EE 00e Semi-Sweet Chocolate 107;66;38 6B4226 http://web.njit.edu/~walsh grey56 143;143;143 8F8F8F DodgerBlue3 24;116;205 1874CD blue3 0;0;205 0000CD Sienna 142;107;35 8E6B23 grey57 145;145;145 919191 DodgerBlue4 16;78;139 104E8B blue4 0;0;139 00008B Tan 219;147;112 DB9370 Shades of Black and Grey grey58 148;148;148 949494 170;187;204 AABBCC abc aqua 0;255;255 00FFFF 0ff Very Dark Brown 92;64;51 5C4033 Color Name RGB Dec RGB Hex CSS Swatch grey59 150;150;150 969696 LightBlue 173;216;230 ADD8E6 cyan 0;255;255 00FFFF 0ff Shades of Green Grey 84;84;84 545454 grey60 153;153;153 999999 999 LightBlue1 191;239;255 BFEFFF cyan1 0;255;255 00FFFF 0ff Dark Green 47;79;47 2F4F2F Grey, Silver 192;192;192 C0C0C0 grey61 156;156;156 9C9C9C LightBlue2 178;223;238 B2DFEE cyan2 0;238;238 00EEEE 0ee DarkGreen 0;100;0 006400 grey 190;190;190 BEBEBE grey62 158;158;158 9E9E9E LightBlue3 154;192;205 9AC0CD cyan3 0;205;205 00CDCD dark green copper 74;118;110 4A766E LightGray 211;211;211 D3D3D3 grey63 161;161;161 A1A1A1 LightBlue4 104;131;139 68838B cyan4 0;139;139 008B8B DarkKhaki 189;183;107 BDB76B LightSlateGrey 119;136;153 778899 789 grey64 163;163;163 A3A3A3 LightCyan 224;255;255 E0FFFF navy 0;0;128 000080 DarkOliveGreen 85;107;47 556B2F SlateGray 112;128;144 708090 grey65 166;166;166 A6A6A6 LightCyan1 224;255;255 -

Mapping Ethnicity: Color Use in Depicting Ethnic Distribution

12 cartographic perspectives Number 40, Fall 2001 Mapping Ethnicity: Color Use in Depicting Ethnic Distribution Jenny Marie Johnson Color effects are in the eye of the beholder. Yet the deepest and truest secrets of color effects are, I know, University of Illinois at invisible even to the eye, and are beheld by the heart alone. Urbana-Champaign (Itten 1970) Maps are made for a specific purpose, or set of purposes. No individual cartographer or cartography-producing organization produces a map just for the sake of producing a map. People and organizations have agendas; maps tell stories. Map stories are told through symbols and colors. Colors have meaning. Perhaps color choice is intended to indi- cate an organization’s attitudes toward the phenomena being mapped. Color on maps of ethnic groups can be evaluated inter-textually by plac- ing the maps into the context of their producers and the time of their production. The colors, and their meanings, that are used to represent particular groups will reflect the map producer’s attitudes toward the ethnic groups. If these attitudes are unknown, they could be hypoth- esized by evaluating color usage. Color choices may act as indicators of opinions otherwise unexpressed. ROLE OF THE ORGANIZATION uch of the thinking about the role that organizations play in produc- ing supposedly scientific maps was done by Harley (1988) during the latter half of his career. He began this work by examining antiquarian maps in a context far greater than the normal “map as beautiful object”. Instead he examined them with the idea that the maps were artifacts produced by agents of organizations with particular goals and objectives. -

Paper Template

SESUG 2016 Paper RV-180 Color Speaks Louder than Words Jaime Thompson, Zencos Consulting ABSTRACT What if color blind people saw real colors and it was everyone else who's color blind? Imagine finishing a Rubik's cube wondering why people find it so difficult. Or relying on the position, rather than the color of a traffic light in determining when to stop and go. Color matters! Color enhances our perspective, it can change how we feel, but it also varies culturally. In western countries, red and white have opposing symbolic meanings to eastern countries which in turn can send the wrong message if misused. Color can fundamentally change a report, therefore, finding the right color palettes for data visualizations is essential. In this paper, I will cover the significance of color and how to pick a palette for your next SAS® Visual Analytics report. INTRODUCTION Color is used in the workplace to improve performance and productivity. Color is used in marketing to establish identity. Color is used in paintings to communicate emotion. Color is used in stores to sell products. Color is everywhere and generally applied purposely. The government of Australia spent several months researching to find the worlds ugliest color. Why? They were looking for a color so distasteful that if it was used for packaging tobacco products it would deter people from smoking [7]. Just as the Australian government needed to pick the right color for a specific job, it is essential to select the right colors for your data visualization so their meanings are conveyed and interpreted correctly. -

Maibec® Color Chart Get Inspired!

maibec® Color Chart Solid Colors Get inspired! Copyright © John DeFiora maibec.com Color themes to fit your environment Each architectural style has its own palette of colors. Finding the right combination for your home’s exterior will bring out its full charm and personality. Our maibec inspirations make it easy. Four professionally- created palettes inspired by nature in traditional and contemporary colors in line with the latest trends: Our Nautilia inspirations bring together soft blues, whites and grays that are reminiscent of ocean breezes and sun-kissed beach homes. Our Balsamia inspirations feature deep blues and greens that are evocative of the peaceful tranquility found in the forest. Our Provincia inspirations use pale whites, yellows and creams to reflect light and emphasize a home’s luster, while bringing to mind rolling hills and the lush countryside. Our Terra inspirations feature rich earth shades of brown, ochre and red that blend seamlessly with the ever-changing beauty of the surrounding woodlands. The colors shown on these color chips may differ slightly once applied to wood. To ensure accuracy, we recommend you order a sample of the desired color prior to ordering your shingles. Cornish-Windsor Bridge Maibec Gray Maibec White Silex Gray 200 206 212 218 Sand Dune Andesite Gray Gray Bridge Pearl Gray 201 207 213 219 Rockbound Coast Maibec Driftwood Roseate Tern Old Port 202 208 214 220 Falcon Gray Oyster Gray Georgian Colonial White Iceberg 203 209 215 221 Maibec Seacoast Cape Cod Gray Humpback Whale Gray Seal 204 210 -

MVHA Historic Color Guidelines

MONTE VISTA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION GUIDELINESGUIDELINES FORFOR COLORSCOLORS ANDAND TEXTURETEXTURE PREPARED BY: THE UTSA COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE TABLE OF CONTENTS Why it is important to choose appropriate paint colors for my home? 1.01 How do I use this guide? 1.02 What do I need to know before I start? 1.03 What style is my house? 1.05 What colors are appropriate for the style of my home? 1.12 Victorian Palette Colonial Revival Palette Neoclassical Palette Tudor Style Palette Italian Renaissance Revival Palette Spanish Inspired Palette Prairie & Craftsman Palette What kind of roof is appropriate for the style of my home? 1.22 Glossary 1.24 Resources for homeowners 1.27 Bibliography 1.29 Image Sources 1.31 MONTE VISTA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION GUIDELINES FOR COLORS AND TEXTURE WHY IT IS IMPORTANT TO CHOOSE APPROPRIATE PAINT COLORS FOR MY HOME? Color is an important defining characteristic of historical homes. Like a home’s deco- rative architectural details, color reflects both the style of a house and the time when it was built. Choosing historically appropriate exterior colors and using them in historically appropriate ways can highlight the architectural character of a home, strengthen its historical integrity and enhance the continuity of an his- toric district. Less appropriate choices can obscure the unique architectural features of a home, weaken its historical value and disrupt the historical context of a neigh- borhood. Recognizing the importance of color to the value of historical homes, several national companies, such as Sherwin-Williams, Benjamin Moore, California Paints and Valspar, have worked with preservation groups like the National Trust for Historic Preserva- tion and Historic New England to produce a wide array of historically accurate colors for consumers. -

Color Harmonization, Deharmonization and Balancing in Augmented Reality

applied sciences Article Color Harmonization, Deharmonization and Balancing in Augmented Reality Emanuele Marino 1,* , Fabio Bruno 1 and Fotis Liarokapis 2 1 Department of Mechanical, Energy and Management Engineering (DIMEG), University of Calabria, Via Pietro Bucci, 87036 Arcavacata di Rende, Italy; [email protected] 2 CYENS—Centre of Excellence, Nicosia 1016, Cyprus; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Color schemes play a crucial role in blending virtual objects with the real environment. Good color schemes improve user’s perception, which is of crucial importance for augmented reality. In this paper, we propose a set of novel methods based on the color harmonization methodology to recolor augmented reality content according to the real background. Three different strategies are proposed—harmonic, disharmonic, and balance—that allow for satisfying different needs in different settings depending on the application field. The first approach aims to harmonize the colors of virtual objects to make them consistent with the colors of the real background and reach a more pleasing effect to a human eye. The second approach, instead, can be adopted to generate a set of disharmonious colors with respect to real ones to be associated with the augmented virtual content to improve its distinctiveness from the real background. The third approach balances these goals by achieving a compromise between harmony and good visibility among virtual and real objects. Furthermore, the proposed re-coloring method is applied to three different case studies by adopting the three strategies to meet three different objectives, which are specific for each case study. Several parameters are calculated for each test, such as the covered area, the color distribution, and the set of Citation: Marino, E.; Bruno, F.; generated colors. -

Commercial Design Guidelines

TOWN OF YUCCA VALLEY COMMERCIAL DESIGN GUIDELINES Community Development Department 58928 Business Center Drive Yucca Valley, CA. 92284 Phone (760) 369-6575 Fax (760) 228-0084 TOWN OF YUCCA VALLEY COMMERCIAL DESIGN GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Page A. Purpose 2 The design guidelines addressed in this section are intended as a reference framework to assist developers and project designers in understanding the Town’s goals and objective for high quality development within the commercial land use districts. B. Applicability 3 This section describes the manner in which the design guidelines should be applied to new and existing development. C. Elements of Project Design 3 This section addresses desirable elements of the commercial project design, as well as undesirable elements that should be avoided. D. Architectural Styles 4 This section provides a framework of common architectural design elements that best reflect the Town’s “desert southwestern” character. Architectural guidelines outlined in this section are intended to be used as guidelines and allow flexibility and to promote creativity. E. Designs Elements $ Colors 9 $ Building Entries 9 $ Building Height 10 $ Building Mass/Scale 11 $ Building Finishes and Detailing 12 $ Roofs 13 $ Awnings 14 $ Materials 14 $ Architectural Details 14 $ Walls and Fences 15 $ Focal Points 16 Glossary 18 A. PURPOSE The design guidelines are intended to assist developers and project designers in understanding the Town’s goals and objectives for achieving, enhancing, and or maintaining high quality development