Self-Exploitation Or Working Time Autonomy? Yandex Taxi Drivers in Moscow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Financialisation of Big Tech

Engineering digital monopolies The financialisation of Big Tech Rodrigo Fernandez & Ilke Adriaans & Tobias J. Klinge & Reijer Hendrikse December 2020 Colophon Engineering digital monopolies The financialisation of Big Tech December 2020 Authors: Rodrigo Fernandez (SOMO), Ilke Editor: Marieke Krijnen Adriaans (SOMO), Tobias J. Klinge (KU Layout: Frans Schupp Leuven) and Reijer Hendrikse (VUB) Cover photo: Geralt/Pixabay With contributions from: ISBN: 978-94-6207-155-1 Manuel Aalbers and The Real Estate/ Financial Complex research group at KU Leuven, David Bassens, Roberta Cowan, Vincent Kiezebrink, Adam Leaver, Michiel van Meeteren, Jasper van Teffelen, Callum Ward Stichting Onderzoek Multinationale The Centre for Research on Multinational Ondernemingen Corporations (SOMO) is an independent, Centre for Research on Multinational not-for-profit research and network organi- Corporations sation working on social, ecological and economic issues related to sustainable Sarphatistraat 30 development. Since 1973, the organisation 1018 GL Amsterdam investigates multinational corporations The Netherlands and the consequences of their activities T: +31 (0)20 639 12 91 for people and the environment around F: +31 (0)20 639 13 21 the world. [email protected] www.somo.nl Made possible in collaboration with KU Leuven and Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) with financial assistance from the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO), grant numbers G079718N and G004920N. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of SOMO and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of any of the funders. Engineering digital monopolies The financialisation of Big Tech SOMO Rodrigo Fernandez, Ilke Adriaans, Tobias J. Klinge and Reijer Hendrikse Amsterdam, December 2020 Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... -

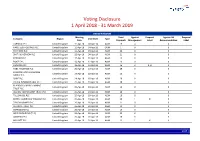

Global Voting Activity Report to March 2019

Voting Disclosure 1 April 2018 - 31 March 2019 UNITED KINGDOM Meeting Total Against Proposal Against ISS Proposal Company Region Vote Date Type Date Proposals Management Label Recommendation Label CARNIVAL PLC United Kingdom 11-Apr-18 04-Apr-18 AGM 19 0 0 HANSTEEN HOLDINGS PLC United Kingdom 11-Apr-18 04-Apr-18 OGM 1 0 0 RIO TINTO PLC United Kingdom 11-Apr-18 04-Apr-18 AGM 22 0 0 SMITH & NEPHEW PLC United Kingdom 12-Apr-18 04-Apr-18 AGM 21 0 0 PORVAIR PLC United Kingdom 17-Apr-18 10-Apr-18 AGM 15 0 0 BUNZL PLC United Kingdom 18-Apr-18 12-Apr-18 AGM 19 0 0 HUNTING PLC United Kingdom 18-Apr-18 12-Apr-18 AGM 16 2 3, 8 0 HSBC HOLDINGS PLC United Kingdom 20-Apr-18 13-Apr-18 AGM 29 0 0 LONDON STOCK EXCHANGE United Kingdom 24-Apr-18 18-Apr-18 AGM 26 0 0 GROUP PLC SHIRE PLC United Kingdom 24-Apr-18 18-Apr-18 AGM 20 0 0 CRODA INTERNATIONAL PLC United Kingdom 25-Apr-18 19-Apr-18 AGM 18 0 0 BLACKROCK WORLD MINING United Kingdom 25-Apr-18 19-Apr-18 AGM 15 0 0 TRUST PLC ALLIANZ TECHNOLOGY TRUST PLC United Kingdom 25-Apr-18 19-Apr-18 AGM 10 0 0 TULLOW OIL PLC United Kingdom 25-Apr-18 19-Apr-18 AGM 16 0 0 BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO PLC United Kingdom 25-Apr-18 19-Apr-18 AGM 20 1 8 0 TAYLOR WIMPEY PLC United Kingdom 26-Apr-18 20-Apr-18 AGM 21 0 0 ALLIANCE TRUST PLC United Kingdom 26-Apr-18 20-Apr-18 AGM 13 0 0 SCHRODERS PLC United Kingdom 26-Apr-18 20-Apr-18 AGM 19 0 0 WEIR GROUP PLC (THE) United Kingdom 26-Apr-18 20-Apr-18 AGM 23 0 0 AGGREKO PLC United Kingdom 26-Apr-18 20-Apr-18 AGM 20 0 0 MEGGITT PLC United Kingdom 26-Apr-18 20-Apr-18 AGM 22 1 4 0 1/47 -

Google, Bing, Yahoo!, Yandex & Baidu

Google, bing, Yahoo!, Yandex & Baidu – major differences and ranking factors. NO IMPACT » MAJOR IMPACT 1 2 3 4 TECHNICAL Domains & URLs - Use main pinyin keyword in domain - Main keyword in the domain - Main keyword in the domain - Main keyword in the domain - Easy to remember Keyword Domain 1 - As short as possible 2 - As short as possible 2 - As short as possible 11 - As short as possible - Use main pinyin keyword in URL - Main keyword as early as possible - Main keyword as early as possible - Main keyword as early as possible - Easy to remember Keyword in URL Path 3 - One specific keyword 3 - One specific keyword 3 - One specific keyword 11 - As short as possible - As short as possible - As short as possible - As short as possible - No filling words - No filling words - As short as possible Length of URL 2 2 2 22 - URL directory depth as brief as possible - No repeat of terms - No repeat of terms - Complete website secured with SSL -No ranking boost from HTTPS - No active SSL promotion - Complete website secured with SSL HTTPS 3 - No mix of HTTP and HTTPS 2 -Complete website secured with SSL 1 - Mostly recommended for authentication 22 - HTTPS is easier to be indexed than HTTP Country & Language - ccTLD or gTLD with country and language directories - ccTLD or gTLD with country and language directories - Better ranking with ccTLD (.cn or .com.cn) - Slightly better rankings in Russia with ccTLD .ru Local Top-Level Domain 3 - No regional domains, e.g. domain.eu, domain.asia 3 - No regional domains, e.g. -

The Calling Card of Russian Digital Antitrust✩ Natalia S

Russian Journal of Economics 6 (2020) 258–276 DOI 10.32609/j.ruje.6.53904 Publication date: 25 September 2020 www.rujec.org The calling card of Russian digital antitrust✩ Natalia S. Pavlova a,b,*, Andrey E. Shastitko a,b, Alexander A. Kurdin b a Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, Moscow, Russia b Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia Abstract Digital antitrust is at the forefront of all expert discussions and is far from becoming an area of consensus among researchers. Moreover, the prescriptions for developed countries do not fit well the situation in developing countries, and namely in BRICS: where the violator of antitrust laws is based compared to national firms becomes an important factor that links competition and industrial policy. The article uses three recent cases from Russian antitrust policy in the digital sphere to illustrate typical patterns of platform conduct that lead not just to a restriction of competition that needs to be remedied by antitrust measures, but also to noteworthy distribution effects. The cases also illustrate the approach taken by the Russian competition authority to some typical problems that arise in digital markets, e.g. market definition, conduct interpretation, behavioral ef- fects, and remedies. The analysis sheds light on the specifics of Russian antitrust policy in digital markets, as well as their interpretation in the context of competition policy in developing countries and the link between competition and industrial policies. Keywords: digital antitrust, competition policy, industrial policy, platforms, multi-sided markets, essential facilities, consumer bias. JEL classification: K21, L41. 1. Introduction Russian antitrust as a direction of economic policy has a relatively short history, but a rich experience in the application of antitrust laws in areas that are considered digital. -

Press-Release Morgan Lewis Advises Yandex 31.08.2021 ENG

Contacts: Emily Carhart Director of Public Relations & Communications +1.202.739.5392 [email protected] Olga Karavaeva Marketing & Communications Manager in Russia +7.495.212.25.18 [email protected] Morgan Lewis Advising Yandex on $1B Acquisition of Interests in Businesses from Uber LONDON and MOSCOW, September 8, 2021: Morgan Lewis is advising Yandex on the restructuring of the ownership of its MLU and Self-Driving joint ventures with Uber, which will see Yandex own 100% of the Yandex.Eats, Yandex.Lavka, Yandex.Delivery and Self-Driving businesses, for consideration of $1.0 billion in cash. Yandex has also received an option to purchase Uber’s remaining stake in MLU over a two-year period for approximately $1.8 billion in cash. Yandex is one of Europe's largest internet companies and a leading search and ride-hailing provider in Russia. The cross-border Morgan Lewis team advising Yandex includes partners Tim Corbett, Nick Moore, Ksenia Andreeva, Anastasia Dergacheva and Omar Shah, and associates Ben Davies, Abbey Brimson, and Leonidas Theodosiou. For more, see Yandex’s announcement. About Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP Morgan Lewis is recognized for exceptional client service, legal innovation, and commitment to its communities. Our global depth reaches across North America, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East with the collaboration of more than 2,200 lawyers and specialists who provide elite legal services across industry sectors for multinational corporations to startups around the world. For more information about us, please visit www.morganlewis.com and connect with us on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and WeChat. -

Why Are Some Websites Researched More Than Others? a Review of Research Into the Global Top Twenty Mike Thelwall

Why are some websites researched more than others? A review of research into the global top twenty Mike Thelwall How to cite this article: Thelwall, Mike (2020). “Why are some websites researched more than others? A review of research into the global top twenty”. El profesional de la información, v. 29, n. 1, e290101. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.ene.01 Manuscript received on 28th September 2019 Accepted on 15th October 2019 Mike Thelwall * https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6065-205X University of Wolverhampton, Statistical Cybermetrics Research Group Wulfruna Street Wolverhampton WV1 1LY, UK [email protected] Abstract The web is central to the work and social lives of a substantial fraction of the world’s population, but the role of popular websites may not always be subject to academic scrutiny. This is a concern if social scientists are unable to understand an aspect of users’ daily lives because one or more major websites have been ignored. To test whether popular websites may be ignored in academia, this article assesses the volume and citation impact of research mentioning any of twenty major websites. The results are consistent with the user geographic base affecting research interest and citation impact. In addition, site affordances that are useful for research also influence academic interest. Because of the latter factor, however, it is not possible to estimate the extent of academic knowledge about a site from the number of publications that mention it. Nevertheless, the virtual absence of international research about some globally important Chinese and Russian websites is a serious limitation for those seeking to understand reasons for their web success, the markets they serve or the users that spend time on them. -

Experience of European and Moscow Metro Systems

EU AND ITS NEIGHBOURHOOD: ENHANCING EU ACTORNESS IN THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS • EURINT 2020 | 303 DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION OF TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE: EXPERIENCE OF EUROPEAN AND MOSCOW METRO SYSTEMS Anton DENISENKOV*, Natalya DENISENKOVA**, Yuliya POLYAKOVA*** Abstract The article is devoted to the consideration of the digital transformation processes of the world's metro systems based on Industry 4.0 technologies. The aim of the study is to determine the social, economic and technological effects of the use of digital technologies on transport on the example of the metro, as well as to find solutions to digitalization problems in modern conditions of limited resources. The authors examined the impact of the key technologies of Industry 4.0 on the business processes of the world's subways. A comparative analysis of the world's metros digital transformations has been carried out, a tree of world's metros digitalization problems has been built, a reference model for the implementation of world's metros digital transformation is proposed. As the results of the study, the authors were able to determine the social, economic and technological effects of metro digitalization. Keywords: Industry 4.0 technologies, digital transformation, transport, metro Introduction The coming era of the digital economy requires a revision of business models, methods of production in all spheres of human life in order to maintain competitive advantages in the world arena. The transport industry is no exception, as it plays an important role in the development of the country's economy and social sphere. The Metro is a complex engineering and technical transport enterprise, dynamically developing taking into account the prospects for expanding the city's borders, with an ever-increasing passenger traffic and integration into other public transport systems. -

Why Digital Sovereignty Requires a European Hyperscaler!

Why Digital Sovereignty requires a European hyperscaler! https://www.unibw.de/code [email protected] Yandex Google Baidu mail.ru/VK Facebook WeChat Amazon Alibaba JD Amazon Google Microsoft Alibaba Tencent Baidu Company Rank Amazon #1 Google #2 Company Rank Facebook #4 Netflix #8 JD.com #3 PayPal #10 Alibaba #5 Salesforce.com #11 Tencent #6 Booking #13 Sunin.com #7 Uber #14 ByteDance #9 Expedia #16 Adobe #18 Baidu #12 eBay #19 12 7 Meituan- #15 Bloomberg #20 Dianping Individuals Industry Governments Military Individuals Industry Governments Military • Lack of options for self-determination • Potential targets in disinformation campaigns • Loss of sensitive private data • Data generation & collection for machine learning Individuals Industry Governments Military • Industrial espionage • Passive through analysis of search engine results and user behavior • Transfer of enormous amounts of European R&D investments • Industrial sabotage • Indirect influence of market capitalization and valuations Endangering European Economic competitiveness Individuals Industry Governments Military • Political instability through disinformation campaigns • Economic instability through induced volatility & loss of competitiveness • Reduction of taxes • Limitation of political scope Individuals Industry Governments Military • Severe disadvantage in future warfware • “Hyperwarfare“ • split-second decision-making w/o humans through automation/AI • automated control of massive amounts of UAVs • Large-scale attacks in cyber domain, overwhelming decision making, reconnaissance, -

Automated Delivery Vehicle State of the Practice Scan

Emerging Automated Urban Freight Delivery Concepts: State of the Practice Scan www.its.dot.gov/index.htm Final Report – November 20, 2020 FHWA-JPO-20-825 Produced by Volpe National Transportation Systems Center U.S. Department of Transportation Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology Intelligent Transportation Systems Joint Program Office Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The U.S. Government is not endorsing any manufacturers, products, or services cited herein and any trade name that may appear in the work has been included only because it is essential to the contents of the work. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-JPO-20-825 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Emerging Automated Urban Freight Delivery Concepts: State of the Practice November 20, 2020 Scan 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Joshua Cregger: ORCID 0000-0002-6202-1443; Elizabeth Machek: ORCID DOT-VNTSC-FHWA-21-01 0000-0002-2299-6924; Molly Behan: ORCID 0000-0002-1523-9589; Alexander Epstein: ORCID 0000-0001-5945-745X; Tracy Lennertz: ORCID 0000-0001-6497-7003; Jingsi Shaw: ORCID 0000-0002-3974-5304; Kevin Dopart: ORCID 0000-0002-0617-8278 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) U.S. Department of Transportation Volpe National Transportation Systems Center 55 Broadway, 11. Contract or Grant No. Cambridge, MA 02142 12. -

Library Discovery from Ponds to Streams

Chapter Five Library Discovery From Ponds to Streams Kenneth J. Varnum esource discovery in libraries has undergone a remarkable evolution over 57 Rthe past five years, tracking (but lagging behind) what has happened on the public Internet. As a handful of companies (Google, Bing, Yahoo!, Yandex, Baidu, etc.) have emerged to provide near-universal access to public information on the Internet, there has been a rising desire within the library world for similar access to licensed content. Libraries, and libraries’ perceptions of the patrons’ needs, have led to the creation and acquisition of “web-scale” discovery services. These new services seek to amalgamate all the content a library might provide access to—the catalog, online journals, abstracting and indexing databases, institutional repositories, open access sites, and more—into a single index. Much like the big companies on the public Internet, these new services build their indexes of content and provide access. PRIMORDIAL DISCOVERY PONDS The evolution of online library research has undergone a significant transformation as well. Not long ago, a library’s online resource portfolio could be thought of as collection of ponds. While they might coexist in a broad ecosystem, they were only A portion of this chapter is based on “Perspective on Discovery,” which was published on RSS4Lib on September 26, 2013, www.rss4lib.com/2013/09/perspective-on-discovery/ Chapter Five loosely connected closer to the surface (if at all). To conduct effective research, a library user would need to navigate to each pond in turn, dip his toes in (or dive in), but then would need to travel to another pond when investigations in the first were completed. -

Global Market Entry for Finnish SME Ecommerce Companies Marko Mäki and Tuija Toivola

Technology Innovation Management Review January 2021 (Volume 11, Issue 1) Global Market Entry for Finnish SME eCommerce Companies Marko Mäki and Tuija Toivola Online shopping is quickly becoming a preferred way to shop for consumers around the globe. Scalefast, 2021 The aim of this paper is to contribute to knowledge about the expansion of eCommerce (eCom) operations by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to global markets. We investigate the literature on eCom and reflect on our experiences working with several Finnish eCom companies and consulting firms to boost their global sales. In addition, one important goal of our study was to acquire knowledge and boost participants’ learning of fast-growing digital business models. Our findings show that digital disruption and digitalization in general are driving forces behind eCom growth. The study’s conclusions underline the importance of targeted marketing activities, knowledge sharing, and capability building for global eCom operations. Introduction eCom growth has become a reality. Even in current strong eCom growth, there is still a lack of studies Competition in many fields of business today has addressing the influence of digitalization on the become global in nature. This trend has been internationalization management of SMEs (see Dethine accelerated by the rapid digitalization of markets and et al., 2020). communication channels. In the global arena, companies compete in environments that deal with Digitalization, in general, offers companies attractive diverse online channel formats, including electronic or strategic opportunities (Abaidi, & Vernette, 2018). For eCommerce (eCom), mobile commerce, and social the first time, almost any company can reach global media (Bilgihan et al., 2016). -

Cloud Platforms and Virtualization Technologies in Education

E3S Web of Conferences 210, 22034 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202021022034 ITSE-2020 Cloud platforms and virtualization technologies in education Mikhail Shevchuk1, Victoria Shevchenko1,*, Evgeniya Chukalovskaya1, Dmitrii Gramakov1 1Moscow State Region University, 10A, st. Radio, 105005, Moscow, Russia Abstract. The article discusses the use of cloud platforms and virtualization technologies, including those based on virtual machines from Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Yandex, Mail.ru for organizing universal training workstations for students with the unification of system and application software for individual study. The main advantages of using cloud-based software over traditional academical one in the educational environment are considered. The great attention is paid to the issues of organizing a virtual workplace in order to increase the effectiveness of training both in the educational organization and outside the classroom. The materials presented were tested at the Department of Computational Mathematics and Methods of Teaching Computer Science in the classroom by the authors of the article. 1 Introduction Today, cloud technology is one of the most topical areas in the development of information and communication technologies. This direction started its grow from cloud services for storing, synchronizing and sharing data, such as Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive, Yandex Disk, Cloud Mail.ru and other similar services. At that time, these services allowed only to store information and exchange it via the Internet. Then, cloud- oriented operating systems and virtual desktops were introduced, which, in addition to accessing files, allowed creating desktops with access to various software - mail clients, calendars, office applications, image editors, etc. The main advantage is that physical resources of the client device are practically not used, while working with such virtual desktop services.