Joseph Neeld and the Grittleton Estate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 Rathill Cottages Grittleton Chippenham SN14 7LB 11 January

2 Rathill Cottages Grittleton Chippenham SN14 7LB 11 January 2017 Mr Richard Sewell Development Services Wiltshire Council Monkton Park Chippenham SN15 1ER Dear Mr Sewell Ref : Ref 18/10196FUL & 16/10522/LBC, 16/10205FUL & 16/10551/LBC, 16/10204/FUL As long standing residents of the Parish of Grittleton (one of us since 1970), we wish to give our full support for the above referenced planning applications. Grittleton is a unique village, and to a large extent we can thank the Neeld family who once owned the Grittleton Estate for the village as we find it today. The massively wealthly Joseph Neeld came from London in 1828 and began a program of remodelling the village and rebuilt Grittleton House. It should be noted that Joseph did not have the hindrance of modern planning laws and no doubt the building of Grittleton House (which adds much character to the village) would never get permission today. However, build it he did, to the benefit of us all. The village continued to be developed right though until the early 20th century at which point to the Neeld family ran out of enthusiasm or money, it seems. The village became stuck in time and very little changed for many years. Of course, in the 1950’s when Grittleton should have taken its fair share of local authority housing, the Neeld family were still able to muster enough energy to ensure that this housing was put in Yatton Keynell , rather than in their own ‘back yard’. Over the past 40 years there has been sporadic in-filling, some of which is sympathetic and some less sympathetic. -

Accommodation List

Accommodation List www.badminton-horse.co.uk Less Than 5 Miles From Badminton Mrs J Baker Contact Details: Honeyston 01249 782148 Nettleton Shrub Nettleton Tel: Chippenham, Wiltshire SN14 7NN Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 3 Double Rooms By prior arrangement 1 Twin Rooms Other Info: Single Rooms Pricing Info: £35 pp/pn (3-4 nights min.) Lift may be available Caroline Baker Contact Details: 39 Station Road 07796 065601 / 014 Tel: Wickwar, South Gloucestershire GL12 8NB Email: caroline [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 1 Double Rooms Easy walking distance to village pub or drive to takeaway & Can provide a 0 Twin Rooms Other Info: 2 Single Rooms Book early for whole house. Whole house available if required and extra beds can be provided. Pricing Info: 5 mile rural route avoids much of the congestion to and from the event. £50 pp/pn No Last Updated: 01 April 2016 www.badminton-horse.co.uk Page 1 of 32 Mr Nick Gauntlett Contact Details: Chescombe Farm 07770 373500 Dodington Road Tel: Chipping Sodbury, South Gloucestershire BS37 6HU Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 3 Double Rooms No 0 Twin Rooms Other Info: 1 Single Rooms Includes Breakfast (Full English/Continental). 4 nights minimum, not en-suite but well appointed in farmhouse. Pricing Info: ALSO - 2 DOUBLE BEDROOM SELF-CONTAINED FLAT @ £40 single/pn, £70 double/night £140/NIGHT (min 4 nights) No Mrs Laura Glynne-Jones Contact Details: Little Maunditts Cottage 01666 824194 / 079 Gaston Lane Tel: Sherston, Wiltshire SN16 0LY Email: [email protected] ACCOMMODATION Evening Meal: 2 Double Rooms Great pub within walking distance - The Rattlebone Inn 1 Twin Rooms Other Info: Single Rooms www.maundittscottage.co.uk All bedrooms ensuite. -

Manor Farm, Leigh Delamere, Chippenham, Wiltshire, SN14

Manor Farm, Leigh Delamere, Chippenham, Wiltshire, SN14 6JZ Imposing Grade II Listed Manor Farmhouse Beautifully Presented Throughout 4 Large Double Bedrooms, 3 Bathrooms 3 Reception Rooms Bespoke Kitchen & Utility Room Magnificent Formal Gardens 4 The Old School, High Street, Sherston, SN16 0LH James Pyle Ltd trading as James Pyle & Co. Registered in England & Wales No: 08184953 Former Tennis Court & Orchard No Onward chain Approximately 3.5 acres Approximately 3,002 sq ft Price Guide: £1,100,000 ‘An exceptional country home not to be missed, set within 3.5 acres of formal gardens and paddocks’ The Property of the home there is an elegant dining hall with Manor Farm is an imposing and quintessential stairs up to the first floor and flagstone flooring semi-detached Grade II Listed period farmhouse which continues to the kitchen. The charming situated within the rural hamlet of Leigh Delamere country style kitchen features exposed timber located for a convenient network to London and beams and is beautifully fitted with handcrafted Situation and Bristol are about 25 minutes by car whilst for the South West. The property sits centrally within bespoke Plain English units alongside an electric those needing to travel further afield, there are its beautiful large gardens with further grounds Everhot, integral dishwasher and fridge/freeze. A The property is located within the rural hamlet of frequent inter-city train services at Chippenham, including pony paddocks and a former tennis useful utility/boot room houses further appliances, Leigh Delamere situated between the larger Bath is just 11 minutes away by train. The M4 court with orchard, the whole extends in all to 3.5 built-in storage, a downstairs WC as well as villages of Grittleton and Stanton St Quinton. -

February 2009

THE BUTTERCROSS BULLETIN The new lifts and bridge at Chippenham Railway Station URGENT MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN – see page 7 Issue No 159 FEBRUARY 2016 In this issue: From the Editor Westinghouse Book Review Report on the Christmas Event A tribute to Jeremy Shaw Membership matters Urgent message from the Chairman Planning Matters Plans for the Langley Park site Our Facebook page What’s in a name? The January talk The Story behind Tugela Road Social programme Deadline for next issue Chairman Isabel Blackburn Astley House 255 London Road Chippenham SN15 3AR Tel: 01249 460049 Email: [email protected] Secretary Vacancy - To be appointed Treasurer Membership Secretary Colin Lynes Marilyn Stone 11 Bolts Croft 26 Awdry Close Chippenham Chippenham SN15 3GQ SN14 0TQ Tel: 01249 448599 Tel: 01249 446385 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 2 From the Editor A Happy New Year to all our readers and welcome to the first Bulletin of 2016 which will be my last as Editor. Hopefully it will not be the last of the Buttercross Bulletins – please read and respond positively to the Chairman’s urgent request on page 7 – ‘Your Society Needs You’. Looking back since 2008 when I began editing the Bulletin, it is good to see the continuing mix of articles and news. Thank you again to those who contribute so we can cover both the history and the culture of Chippenham past and the wealth of activities and energy devoted to ensuring a vibrant modern town. Once again it is that time of year when we look forward to the Conservation and Environment Awards evening in May. -

Sevington Farm, Sevington, Grittleton, Chippenham, Wiltshire, SN14

Sevington Farm, Sevington, Grittleton, Chippenham, Wiltshire, SN14 7LD Substantial Grade II Listed Farmhouse Planning permission to convert outbuildings 6 Bedrooms, 3 Bathrooms Four Receptions Aga Kitchen/Breakfast Room 4 The Old School, High Street, Sherston, SN16 0LH Period Character Throughout James Pyle Ltd trading as James Pyle & Co. Registered in England & Wales No: 08184953 Large Gardens & Paddock Ample Parking Rural setting Price Guide: £1,350,000 Approximately 3.2 acres Approximately 5,456 sq ft ‘Set within the rural hamlet of Sevington, a handsome and substantial Grade II Listed period farmhouse together with some 3.2 acres of grounds and paddocks, plus planning permission to create a holiday let’ The Property access to the garden and a rear boot room The gardens are predominantly arranged to village of Castle Combe famous for its off. The large farmhouse kitchen/breakfast the east side of the farmhouse laid to lawn unspoilt character, fine hotel and Golf Sevington Farm is a handsome Grade II room has an Aga and fitted units with with a small orchard, whilst there is a Club. The market town of Chippenham is listed period farmhouse set within 3.2 acres granite worksurfaces arranged around a further lawn garden off the living room. only 4 miles away for a further range of of grounds and pastureland. The farmhouse central island with a ceramic hob, off The large paddock extends to 2.7 acres. facilities, and both Bath and Bristol are dates to the 18th Century once belonging to which is a utility/boiler room. within a 30 minutes' drive. -

RHO Volume 35 Back Matter

WORKS OF THE CAMDEN SOCIETY AND ORDER OF THEIR PUBLICATION. 1. Restoration of King Edward IV. 2. Kyng Johan, by Bishop Bale For the year 3. Deposition of Richard II. >• 1838-9. 4. Plumpton Correspondence 6. Anecdotes and Traditions 6. Political Songs 7. Hayward's Annals of Elizabeth 8. Ecclesiastical Documents For 1839-40. 9. Norden's Description of Essex 10. Warkworth's Chronicle 11. Kemp's Nine Daies Wonder 12. The Egerton Papers 13. Chronica Jocelini de Brakelonda 14. Irish Narratives, 1641 and 1690 For 1840-41. 15. Rishanger's Chronicle 16. Poems of Walter Mapes 17. Travels of Nicander Nucius 18. Three Metrical Romances For 1841-42. 19. Diary of Dr. John Dee 20. Apology for the Lollards 21. Rutland Papers 22. Diary of Bishop Cartwright For 1842-43. 23. Letters of Eminent Literary Men 24. Proceedings against Dame Alice Kyteler 25. Promptorium Parvulorum: Tom. I. 26. Suppression of the Monasteries For 1843-44. 27. Leycester Correspondence 28. French Chronicle of London 29. Polydore Vergil 30. The Thornton Romances • For 1844-45. 31. Verney's Notes of the Long Parliament 32. Autobiography of Sir John Bramston • 33. Correspondence of James Duke of Perth I For 1845-46. 34. Liber de Antiquis Legibus 35. The Chronicle of Calais J Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.35.93, on 27 Sep 2021 at 13:24:50, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2042169900003692 CAMDEN K^AHkJ|f SOCIETY, FOR THE PUBLICATION OF EARLY HISTORICAL AND LITERARY REMAINS. -

Sevington Hall, Sevington, Grittleton, Chippenham, Wiltshire, SN14

Sevington Hall, Sevington, Grittleton, Chippenham, Wiltshire, SN14 7LD Grade II Listed 1820s Barn High Quality Finish Wealth of Charm & Character 4 Double Bedrooms, 3 Bathrooms 2 Receptions Impressive Galleried Hall 4 The Old School, High Street, Sherston, SN16 0LH Gardens & Large Paddock James Pyle Ltd trading as James Pyle & Co. Registered in England & Wales No: 08184953 Approximately 3.4 acres Approximately 3,584 sq ft Price Guide: £1,200,000 ‘Set within this pretty hamlet, Sevington Hall is a truly outstanding Grade II listed barn showcasing magnificent period features and high quality finishes coupled with gardens and paddock of c.3.4 acres’ The Property fridge/freezer and wine cooler under Italian borders. The paddock is located to the north of M4 (Junction 18) is about 5 minutes' drive Blondo quartz worktops. the barn with gated access from both the away providing access to London, the south and Sevington Hall is a truly outstanding Grade II parking area and the garden. The paddock the Midlands. Listed barn conversion boasting 3.4 acres of The kitchen is open to the large dining/family extends to 2.44 acres and gently slopes towards gardens and paddocks set within the pretty room which has a woodburning stove and door a copse of sycamore and pine trees at the far Tenure & Services hamlet of Sevington. Believed to date back to to the garden. Interconnecting through the hall, northern border. 1820 forming part of the Neeld Estate, the barn the spacious living room mirrors the family We understand the property is Freehold with oil is constructed of Cotswold stone with a half- room and also features a wood burner. -

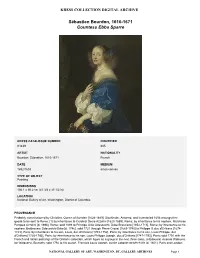

Summary for Countess Ebba Sparre

KRESS COLLECTION DIGITAL ARCHIVE Sébastien Bourdon, 1616-1671 Countess Ebba Sparre KRESS CATALOGUE NUMBER IDENTIFIER K1439 605 ARTIST NATIONALITY Bourdon, Sébastien, 1616-1671 French DATE MEDIUM 1652/1653 oil on canvas TYPE OF OBJECT Painting DIMENSIONS 106.1 x 90.2 cm (41 3/4 x 35 1/2 in) LOCATION National Gallery of Art, Washington, District of Columbia PROVENANCE Probably commissioned by Christina, Queen of Sweden [1626-1689], Stockholm, Antwerp, and inventoried 1656 amongst her goods to be sent to Rome; [1] by inheritance to Cardinal Decio Azzolini [1623-1689], Rome; by inheritance to his nephew, Marchese Pompeo Azzolini [d. 1696], Rome; sold 1696 to Principe Livio Odescalchi, Duke Bracciano [1652-1713], Rome; by inheritance to his nephew, Baldassare Odescalchi-Erba [d. 1746]; sold 1721 through Pierre Crozat [1665-1740] to Philippe II, duc d'Orléans [1674- 1723], Paris; by inheritance to his son, Louis, duc d'Orléans [1703-1752], Paris; by inheritance to his son, Louis Philippe, duc d'Orléans [1725-1785], Paris; by inheritance to his son, Louis Philippe Joseph, duc d'Orléans [1747-1793], Paris; sold 1791 with the French and Italian paintings of the Orléans collection, which figure as a group in the next three sales, to Edouard, vicomte Walkuers [or Walquers], Brussels; sold 1792 to his cousin, François Louis Joseph, comte Laborde de Méréville [d. 1801], Paris and London; NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON, DC, GALLERY ARCHIVES Page 1 KRESS COLLECTION DIGITAL ARCHIVE on consignment until 1798 with (Jeremiah Harman, London); sold 1798 through (Michael Bryan, London) to a consortium of Francis Egerton, 3rd duke of Bridgewater [1736-1803], London and Worsley Hall, Lancashire, Frederick Howard, 5th earl of Carlisle [1748- 1825], Castle Howard, North Yorkshire, and George Granville Leveson-Gower, 1st duke of Sutherland [1758-1833], London, Trentham Hall, Stafford, and Dunrobin Castle, Highland, Scotland. -

Remote Meeting 16Th September 2020 Draft

MINUTES OF THE REMOTE MEETING OF THE STANTON ST QUINTIN PARISH COUNCIL HELD BY ZOOM ON 16th SEPTEMBER 2020 1. Present: Mr A. Andrews (Chairman); Mr E. Crossley; Capt J. Godwin; Mrs G. Horton Mrs Carey (Clerk) 2. Apologies: Nil 3. Absent: Mrs S. Parker; Mrs R. Whiting 4. Public Question Time: There were four members of the public present Rob Hill, Director of Global Capital Projects, Dyson and Debbie Greaves, Project Manager joined the meeting and spoke about the proposals for the roundabout on the A429. There would also be a second roundabout on the A429/Hullavington village. This would remove the dangerous junction that there is at present. The work had started earlier this year and will impact on the main highways in October/November. The work should be completed shortly after Christmas Debbie Greaves stated that there will be a website update next week and a newsletter sent out 5. Chairman’s announcements and declarations of interest: Nil 6. Minutes: The Minutes of the Meetings held on 8th July and 24th August 2020 were taken as read and will be signed as being a true record at the next proper meeting. 7. Matters Arising: a. Highway issues: • Litter by the garage: Continue to monitor • Damage to the Village triangle/verges in Lower village: Update from Wiltshire Council. This Highways Improvement request has been added to the list of requests to be considered by the Chippenham CATG. Clerk to pursue this with Wiltshire Highways • JunctionDraft of Seagry Road with 429: See update given above • Parish Steward visits: Clerk to obtain dates of future meetings • Speed Limits: Issue sheets had been submitted to CATG • Posts on village green – issue sheet had been submitted. -

View in Website Mode Chippenham Sheldon School

74 bus time schedule & line map 74 Grittleton - Leigh Delamere - Yatton Keynell - View In Website Mode Chippenham Sheldon School The 74 bus line (Grittleton - Leigh Delamere - Yatton Keynell - Chippenham Sheldon School) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chippenham: 7:28 AM (2) The Gibb: 3:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 74 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 74 bus arriving. Direction: Chippenham 74 bus Time Schedule 10 stops Chippenham Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:28 AM Salutation Inn, the Gibb Tuesday 7:28 AM The School, Grittleton Wednesday 7:28 AM The Green, Sevington Thursday 7:28 AM Manor Farm, Leigh Delamere Friday 7:28 AM Crossroads, Grittleton Saturday Not Operational Clarkes Leaze, Yatton Keynell Bell Inn, Yatton Keynell 74 bus Info Home Fields, Yatton Keynell Civil Parish Direction: Chippenham Farrells Field, Yatton Keynell Stops: 10 Trip Duration: 42 min Line Summary: Salutation Inn, the Gibb, The School, Bythebrook, Chippenham Grittleton, The Green, Sevington, Manor Farm, Leigh Bythebrook, Chippenham Civil Parish Delamere, Crossroads, Grittleton, Clarkes Leaze, Yatton Keynell, Bell Inn, Yatton Keynell, Farrells Field, Sheldon School, Chippenham Yatton Keynell, Bythebrook, Chippenham, Sheldon School, Chippenham Direction: The Gibb 74 bus Time Schedule 11 stops The Gibb Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 3:10 PM Sheldon School, Chippenham Tuesday 3:10 PM Bythebrook, Chippenham Wednesday 3:10 PM Willowbank, -

Appeal Decisions

Appeal Decisions Site visit made on 24 November 2014 by R M Barrett BSc (Hons) MSc Dip UD Dip Hist Cons MRTPI IHBC an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government Decision date: 8th December 2014 Appeal Ref: APP/Y3940/A/14/2224810 (Appeal A) Sevington Hall, Sevington, Grittleton, Chippenham SN14 7LD • The appeal is made under section 78 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 against a refusal to grant planning permission. • The appeal is made by Mr and Mrs Bridges against the decision of Wiltshire Council. • The application Ref 14/03327/FUL, dated 21 March 2014, was refused by notice dated 20 May 2014. • The development proposed is planting of a new hedgerow and fence along the east elevation with gate entrance. Construction of a new single storey link between the existing house and outbuilding. Appeal Ref: APP/Y3940/E/14/2227531 (Appeal B) Sevington Hall, Sevington, Grittleton, Chippenham SN14 7LD • The appeal is made under section 20 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 against a refusal to grant listed building consent. • The appeal is made by Mr and Mrs Bridges against the decision of Wiltshire Council. • The application Ref 14/03375/LBC, dated 21 March 2014, was refused by notice dated 20 May 2014. • The works are described as planting of a new hedgerow and fence along the east elevation with gate entrance. Construction of a new single storey link between the existing house and outbuilding. Decision 1. Both appeals are dismissed. Procedural Matter 2. Amended plans were submitted at appeal Ref 031701.1A; 031701.2A; 0317 01.4A; 031701.5A; 031701.6A; 031701.7A; 031704.1A; 031704.2A; 031704.3A; 031704.4A; 031704.5A. -

Wiltshire - Grooms Index (Surnames P)

Wiltshire - Grooms Index (Surnames P) Year Groom Surname Given Names Parish of Marriage 1708 P? Charles Stanton St. Quinton 1609 P? Richard Stratton St. Margaret 1642 P[?] William Chilton Foliat 1666 P[a]nnell Richard Lydiard Millicent 1653 Pa Robert Semington 1696 Paber Edward Bradford-on-Avon - Holy Trinity 1771 Pack William Melksham 1779 Packatt John Salisbury St. Edmunds 1714 Packer Ambrose Baydon 1769 Packer Anthony Ashton Keynes 1776 Packer Arthur Langley Burrell 1788 Packer Benjamin Bradford-on-Avon - Holy Trinity 1816 Packer Benjamin South Wraxall 1750 Packer Daniel Langley Burrell 1784 Packer Daniel Melksham 1733 Packer Daniell Corsham 1672 Packer Edward Hankerton 1769 Packer Edward Lydiard Millicent 1722 Packer Edward Minety 1729 Packer Edward Minety 1724 Packer Francis Somerford Keynes 1705 Packer Giles Eisey (Eysey) 1739 Packer Giles Kemble 1768 Packer Giles Oaksey 1765 Packer Harry Ashton Keynes 1769 Packer Harry Ashton Keynes 1804 Packer Harry Ashton Keynes 1810 Packer Harry Ashton Keynes 1708 Packer Henry Ashton Keynes 1744 Packer Henry Ashton Keynes 1811 Packer Henry Cricklade 1834 Packer Henry Hullavington 1743 Packer Henry Minety 1826 Packer Henry Minety 1836 Packer Henry Minety 1826 Packer Henry Southbroom 1929 Packer Horace Sidney Chippenham Lowden & Sheldon Rd 1776 Packer James Langley Burrell 1713 Packer James Purton with Braydon 1792 Packer James Trowbridge St. James 1742 Packer John Aldbourne 1777 Packer John Aldbourne 1734 Packer John Castle Eaton 1753 Packer John Colerne 1817 Packer John Cricklade 1739 Packer John Devizes St. John 1758 Packer John Leigh 1702 Packer John Long Newnton 1731 Packer John Malmesbury 1769 Packer John Marlborough St. Peter & St.