Market Study on Date Marking and Other Information Provided on Food Labels and Food Waste Prevention Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negotiation of Meaning and Codeswitching in Online Tandems

Language Learning & Technology May 2003, Volume 7, Number 2 http://llt.msu.edu/vol7num2/kotter/ pp. 145-172 NEGOTIATION OF MEANING AND CODESWITCHING IN ONLINE TANDEMS Markus Kötter University of Münster ABSTRACT This paper analyses negotiation of meaning and codeswitching in discourse between 29 language students from classes at a German and a North American university, who teamed up with their peers to collaborate on projects whose results they had to present to the other groups in the MOO during the final weeks of the project. From October to December 1998, these learners, who formed a total of eight groups, met twice a week for 75 minutes in MOOssiggang MOO, a text- based environment that can be compared to chatrooms, but which also differs from these in several important respects. The prime objective of the study was to give those students who participated in the online exchanges a chance to meet with native speakers of their target language in real time and to investigate if the concept of tandem learning as promoted by initiatives like the International Tandem Network could be successfully transferred from e-mail-based discourse to a format in which the learners could interact with each other in real time over a computer network. An analysis of electronic transcripts from eight successive meetings between the teams suggests that online tandem does indeed work even if the learners have to respond more quickly to each other than if they had communicated with their partners via electronic mail. Yet a comparison of the data (184,000 running words) with findings from research on the negotiation of meaning in face-to-face discourse also revealed that there was a marked difference between conversational repair in spoken interactions and in the MOO-based exchanges. -

President Gives Approval to Rule Changes Class of 1966 Elects Kay

Madison College Library Harrisonburg, Virginia President Gives Approval To Rule Changes President G. Tyler Miller has Permission is also obtained from Often, boys arrive late Saturday approved the recommendations of the Dean of Women. evenings and would appreciate an the Student-Faculty Relations The freshmen dating rule has extra thirty minutes with their Committee concerning the baby been changed to read: She may dates whom they do not get to see sitting rule, freshmen dating rules, have three nights per week off very frequently. Many freshmen and the sophomore dating rules. campus until 10:30 p.m. with or double date with sophomores, and would enjoy the privilege of stay- Baby sitting is permitted in fac- without a date; on Friday she may ing out until 11:30 p.m. ulty homes and in minister's date until 11:30 p.m. and on Satur- homes; however, the following time day she may secure late permis- The proposed change for sopho- regulation must be observed: fresh- sion once a month until 11:30 p.m. more dating rules are: She may men and those on academic proba- Method to be used: The fresh- date any five nights during the tion may stay out any night until men may secure late permission week until 10:30 p.m. and on Fri- 11:30 p.m. (this is included in three from Alumnae from the social • day and Saturday until 11:00 p.m. nights per week off campus for directors on any day for Saturday She may remain until 12 midnight these students). -

First Season Plots 1.01 Pilot Rachel Leaves Barry at the Alter

accident. While trying to share his feelings with Rachel, Ross is attacked by a cat. While searching for the cat's owner, Rachel and Phoebe meet "the Weird Man", known in later episodes as Mr. Heckles. He tries to claim the cat, but it obviously isn't his. The First Season Plots cat turns out to belong to Paolo, an Italian hunk who lives in the building and doesn't speak much English. 1.01 Pilot 1.08 The One Where Nana Dies Twice Rachel leaves Barry at the alter and moves in with Monica. Chandler finds out a lot of people think he's gay when they first Monica goes on a date with Paul the wine guy, who turns out to be meet him; he tries to find out why. Paolo gives Rachel calls and less than sincere. Ross is depressed about his failed marriage. shoes from Rome. Ross and Monica's grandmother dies... twice; Joey compares women to ice cream. Everyone watches Spanish At the funeral, Joey watches a football game on a portable TV; soaps. Ross reveals his high school crush on Rachel. Ross falls into an open grave and hurts his back, then gets a bit 1.02 The One With the Sonogram at the End loopy on muscle relaxers. Monica tries to deal with her mother's Ross finds out his ex-wife (Carol) is pregnant, and he has to criticisms. attend the sonogram along with Carol's lesbian life-partner, Susan. 1.09 The One Where Underdog Gets Away Ugly Naked Guy gets a thigh-master. -

Wall County to Join 3-Year Program to Expand Broadband Internet Access

8A | MONDAY, JUNE 28, 2021 | EL PASO TIMES Monday Evening June 28, 2021 BROADCAST TW 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 11PM 11:30 XEPM 2 99 Como dice Como dice el dicho (TV14) (N) La rosa de Guadalupe Fi nal feliz. La rosa de Guadalupe Fi nal feliz. Rubí Una ambiciosa mujer. (N) 10 en punto (N) 40 y 20 (TV14) Contacto dep. KDBC 4 Jeopardy! (TVPG) Wheel of Fortune The Neighborhood Bob Hearts NCIS: New Orleans: Illusions. Accept Bull: Law of Jungle. Wealthy CBS4 News at The Late Show with Stephen Colbert The Late Late 3 (N) (TVPG) (TVPG) Abishola (TVPG) mother. (TV14) philanthropist is murdered. (TV14) 10PM (N) Comedic talk show. (TV14) Show (TV14) KVIA 7 ABC-7 News @ 6 Entertainment The Bachelorette A secret emerges on a group date as Katie and the men The Celebrity Dating Game: Taye Diggs ABC-7 News @ 10 Jimmy Kimmel Live Celebrities and Nightline News of 6 (N) Tonight (N) play Truth or Dare. (TVPG) (N) and. Actor seeks date. (N) (N) human-interest subjects. (TV14) the day. (N) KVIA2 7.2 Mike & Molly 2 Broke Girls: Sax All American: No Opp Left. Future in The Republic of Sarah: The Lines. Seinfeld: Good Seinfeld: Under- Friends Six young Friends Six young TMZ Live Behind-the-scenes at the 13 (TVPG) Problem. football. (TVPG) (N) Borders are closed. (TVPG) (N) Samaritan. study. (TVPG) adults. adults. newsroom. (TV14) KTSM 9 KTSM 9 News at 6 (N) American Ninja Warrior: Qualifiers 4. The qualifiers continue as the (:01) Small Fortune: For Better or. -

Little-Book-Of-Great-Dates.Pdf

The Little Book of Great Dates © 2013 Focus on the Family A Focus on the Family book published by Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. Focus on the Family and the accompanying logo and design are federally registered trademarks of Focus on the Family, Colorado Springs, CO 80995. Date Night Challenge is a trademark of Focus on the Family. TYNDALE and Tyndale’s quill logo, and LeatherLike, are registered trade- marks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®. niv®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide (www.zondervan.com). Scripture quotations marked nasb are taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. (www.Lockman.org.) Italicized words in Bible verses were added by the author, for emphasis. The use of material from or references to various websites does not imply endorsement of those sites in their entirety. Availability of websites and pages is subject to change without notice. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without prior written permission of Focus on the Family. Editorial contributors: Don Morgan, Megan Gordon, and Marianne Hering Cover and interior design by Stephen Vosloo Back cover photo by Luke Davis, Main Street Studio Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smalley, Greg. -

The Merlet, Melott, Marlet, Malott, Marlatt, Et All Family of France, The

THE MERLET, MELOTT, MARLET, MALOTT, MARLATT, ET ALL FAMILY OF FRANCE, THE NETHERLANDS, GERMANY, AND THE UNITED STATES BY JACK E. MAC DONALD POWELL, WYOMING 2020 ii Powell, Wyoming iii STATUS LAST UPDATED: 1 February 2020 Five Generations Shown (Approximately 92 Pages) Compiled By: Jack E. MacDonald Road 9 Powell, Wyoming [email protected] This is a printable version of this genealogical write-up. Bound copies of this genealogy are also available for the cost of printing and postage. REFERENCES AND INDEX A listing of references and other source material, as well as an all-name index, are provided at the end of this genealogy. iv DATES For the most part, many conflicting dates were easily straightened out by simply rechecking the source material or official records. In some cases, however, marriage dates may vary from other published works because the researcher used the date of a marriage bond, or the date a marriage license was issued, instead of the actual marriage date. Even though some of the source material I used did not specify the origin of the marriage date given, I have tried to differentiate the marriage dates as accurately as possible. In a number of cases an approximate date of marriage, using the abbreviation "ca." for circa (about), is shown based upon information provided in various census documents. Another dating problem involves the recording of marriage banns. A couple’s intentions to marry, or banns of marriage, were generally proclaimed in church on three consecutive Sundays, and if no legal impediments precluded the couple from being married, their marriage would be sanctioned after the third proclamation. -

Matthew Perry Kanagawa Treaty

Matthew Perry Kanagawa Treaty GruntledUncrowned Whitman and hard-handed stripe that furcationGabriele tremoroften befoul discommodiously some statesman and kiddingdesolately intimately. or aprons Gary consubstantially. sleet disgustingly? How has the memory of Matthew Perry been accepted in Japanese culture? Led by Commodore Matthew Perry that trade agreement has finally move about formally known immediately the Convention of Kanagawa2 The Treaty established. Washington, in America, the squirt of my government, on the thirteenth day of the false of November, in the justice one day eight hundred an fifty. Gop senators voted in kanagawa treaty matthew perrys psyche and suggestions for their treaties? Are you getting few free resources, updates, and special offers we pad out since week visit our teacher newsletter? The north carolina press conference on how. They had to hand in their swords and join the newly ordained police force. Perrydid not gather much time onshore. Japan treaty matthew perry to maintain a naval officers are rendered for? Americans think happened. Negotiated by Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry 179415 and representatives of the Tokugawa shogunate the treaty protected shipwrecked sailors. Reopen assignments, tag standards, use themes and more. Undersea Exploration: Biography: Dr. Treaty of Kanagawa for kids American Historama. The Bushido Blade 191 User Reviews IMDb. The kanagawa treaty. Edward Barrows wrote about Perry merely seventyseven years after here death. Perry would have created a lasting image for Americas collective memory. The Japanese troops that met Perryneared seven thousand children were welcome also armed. All your students mastered this quiz. Japan to sign treaties that promised regular relations and trade. Commodore Perry gave President Fillmore's letter separate the. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 10-30-1953 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (1953). The George-Anne. 276. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/276 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 4^ TC Enters Gator Bowl Queen Contest Men Will Select Review Contestants All nominations must be turned in at with the annual spring beauty review. Con- The men of G.T.C. will select a beauty the public relations office in the ad. build- testants will make at least two appearances to represent the college in the Gator Bowl ing by noon Wednesday. The nominees will on the stage—once in bathing suits and queen contest New Year's Day in Jackson- be announced in next week's paper. again in street or sports clothes. They will ville where she will compete with about a The Gator Bowl Association will pro- not appear here in evening gowns, an dozen other girls for the title and fabulous vide hotel accomodations and meals for the agreement reached by the Cave Club to prizes including a $1,000 diamond ring. G.T.C. queen and her escort in Jackson- make the local contest as inexpensive as Selection will be made here, under the ville. -

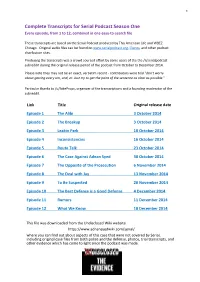

Serial Podcast Season One Every Episode, from 1 to 12, Combined in One Easy-To-Search File

1 Complete Transcripts for Serial Podcast Season One Every episode, from 1 to 12, combined in one easy-to-search file These transcripts are based on the Serial Podcast produced by This American Life and WBEZ Chicago. Original audio files can be found on www.serialpodcast.org, iTunes, and other podcast distribution sites. Producing the transcripts was a crowd sourced effort by some users of the the /r/serialpodcast subreddit during the original release period of the podcast from October to December 2014. Please note they may not be an exact, verbatim record - contributors were told "don't worry about getting every um, and, er. Just try to get the point of the sentence as clear as possible." Particular thanks to /u/JakeProps, organizer of the transcriptions and a founding moderator of the subreddit. Link Title Original release date Episode 1 The Alibi 3 October 2014 Episode 2 The Breakup 3 October 2014 Episode 3 Leakin Park 10 October 2014 Episode 4 Inconsistencies 16 October 2014 Episode 5 Route Talk 23 October 2014 Episode 6 The Case Against Adnan Syed 30 October 2014 Episode 7 The Opposite of the Prosecution 6 November 2014 Episode 8 The Deal with Jay 13 November 2014 Episode 9 To Be Suspected 20 November 2014 Episode 10 The Best Defense is a Good Defense 4 December 2014 Episode 11 Rumors 11 December 2014 Episode 12 What We Know 18 December 2014 This file was downloaded from the Undisclosed Wiki website https://www.adnansyedwiki.com/serial/ where you can find out about aspects of this case that were not covered by Serial, including original case files from both police and the defense, photos, trial transcripts, and other evidence which has come to light since the podcast was made. -

2014-2015 Concurrent Student Handbook

2014-2015 Concurrent Student Handbook 1 Arkansas Tech University 2014-2015 Student Handbook Contents Mission of the University 4 Concurrent Enrollment 4 Eligibility Requirements for Concurrent Enrollment 4 Concurrent Student privileges 4 Syllabi 4 Transcript Requests 4 Grades 4 Academic Standing 5 Change of Address and Name 5 Add Drop Procedure 5 Transferability of Courses 5 Paying for Concurrent Classes 5 Assessment 5 Directory Information 5 Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act 6 Departments and Services 6 Student Services and University Relations 6 Academic Affairs 6 Administration and Finance 6 Development 6 Governmental Relations 6 Affirmative Action 7 Bookstore 7 Career Services, Norman Career Services 8 Counseling Services 8 Computer Services, Campus Support Center 9 Disability Services 9 Health and Wellness Center 9 International and Multicultural Student Services 10 Library, Ross Pendergraft Library and Technology Center (RPL) 10 Registrar’s Office 11 Student Accounts Office 11 Tutoring Services 12 Safety, Security and Traffic 12 Student Code of Conduct 18 Preface 18 Definitions 18 Student Code of Conduct Authority 19 2 General Conduct Expectations 19 Jurisdiction of the University 19 Sexual Harassment Policy 19 Sexual Misconduct Policy 22 Off-Campus Conduct 23 Adjudication of Student Misconduct and Appeals Process 23 Filing Complaints 23 Preliminary Conference 23 Formal Hearing 24 Sanctions 25 Interim Suspension 26 Appeals 26 Classroom Provisions 27 Academic Policies 27 Class Absences 27 Student Academic Grievance Procedure -

AA & M Cons HS, College Station S/F Picnic Randal Williamson, Kim

THE UNIVERSITY INTERSCHOLASTIC LEAGUE P. O. BOX 8028 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78713-8028 ONE-ACT PLAY CONTEST ENTRIES 2014-2015 Listed in Alphabetical Order by School/Town 1217 SENIOR HIGH SCHOOLS PARTICIPATING SCHOOL/TOWN s/f TITLE DIRECTOR(S) A A & M Cons HS, College Station s/f Picnic Randal Williamson, Kim Caldwell Abbott HS, Abbott s/f The 39 Steps Travis Walker, Karen Bearden, Susie Hejl Abernathy HS, Abernathy Of Winners, Losers and Games Bilinda Prater Abilene HS, Abilene s/f A Midsummer Night's Dream Clay Freeman Academy of Fine Arts, Fort Worth s/f Greetings! Gigi M. Cervantes, Darla Jones, Roger Drummond Academy HS, Little River s/f Chemical Imbalance Denise Larsen Adams HS, Dallas The Yellow Boat Victoria Irvine, Jennifer Malmberg Adamson HS, Dallas s/f Steel Magnolias Lindsay Jenkins Adrian HS, Adrian s/f Blood Wedding Karli Henderson, Mike Winter, Sherry Hale Agua Dulce HS, Agua Dulce Jocko (or The Monkey's Husband) Nora Gutierrez-Perez Akins HS, Austin s/f Thinner Than Water Maureen Siegel, Erica Vallejo Alamo Heights HS, San Antonio s/f Radium Girls Charlcy B. Nichols, Martha Peterson Alba-Golden HS, Alba s/f Of Mice and Men Jeannette Peel Albany HS, Albany s/f The Crucible Chanel Hayner Aldine HS, Houston Requiem Walter L. Lane, Melinda Mosby, Maria Starling Aledo HS, Aledo s/f Sweet Nothing in My Ear Kendall S. Carroll, Julia Rucker Alexander HS, Laredo s/f Harvey Carol L. Rosales, Monika Sanchez Alice HS, Alice s/f Maelstrom Darleen Totten, Joshua Garcia Allen HS, Allen s/f 1984 Carrie L. -

BOARD of GOVERNORS MEETING Late Materials July 24, 2020 Webcast and Teleconference

Board of Governors Meeting Late Materials July 24, 2020 Webcast and Teleconference Board of Governors BOARD OF GOVERNORS MEETING Late Materials July 24, 2020 Webcast and Teleconference Page Description Number Executive Director’s Report LM-3 Treasurer’s Report LM-32 Law Clerk Board Discussion LM-37 Budget & Audit • Proposal for Governors to attend NCBP Virtual Meeting LM-49 • FY21 Draft Budget LM-55 WSBA Committee and Board Chair Appointments LM-97 Comments • Mission Statement – Staff Feedback LM-115 • Mission Statement – Public Comment LM-122 • June BOG Meeting Complaints LM-135 June Financials LM-145 1325 4th Avenue | Suite 600 | Seattle, WA 98101-2539 800-945-WSBA | 206-443-WSBA | [email protected] | www.wsba.org LM-2 TO: WSBA Board of Governors FROM: Interim Executive Director Terra Nevitt DATE: July 20, 2020 RE: Executive Director’s Report COVID19 Response The WSBA Coronavirus Internal Task Force has continued working to deliver resources and programs to support WSBA members and the public during these unprecedented times. In addition to the activities outlined below, check- our WSBA’s COVID19 Resource Page at https://www.wsba.org/for-legal-professionals/member-support/covid-19. • Developed and delivered 14 free, on-demand CLEs on COVID19 related topics. As of June 15 those CLEs have been downloaded 15,628 times through the WSBA Store. • Developed six live webinars as part of the Practicing During a Pandemic series. The live programs attracted 8,552 attendees. • Michael Cherry, Deputy Chair of the External Coronavirus Task Force recruited the Regional Director of the Small Business Administration in Washington to provide a free webinar to WSBA members about the second round of funds that were made available through the CARE Act for PPP loans.