Morris, William 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Batman Returns", Unproduced Draft, by Sam Hamm

"Batman Returns", unproduced draft, by Sam Hamm BATMAN 2 Screenplay By Sam Hamm FIRST DRAFT NOTE: THE HARD COPY OF THIS SCRIPT CONTAINED SCENE NUMBERS. THEY HAVE BEEN REMOVED FOR THIS SOFT COPY. NOTE ALSO: THE HARD COPY OF THIS SCRIPT WAS IN THE NON- PREFORMAT FONT "BOOKMAN OLD". THIS HAS BEEN CHANGED TO PREFORMATTED TEXT FOR THIS SOFT COPY. EXT. GOTHAM SQUARE - DUSK It's finally happened. Hell's frozen over. Christmas is two weeks off, arid SNOW is falling in Gotham. Beneath its pristine white blanket, the city looks uncharacteristically serene -- almost inviting. Peace has been miraculously restored: strangers wave hello. Salvation Army Santas ring their bells on streetcorners. And now, as night falls, an ILLUMINATED SIGN winks on above Broad Avenue: "JOYEUX NOEL GOTHAM -- Only 16 Shopping Days Left Till Christmas." The streets are bustling with jolly shoppers. At a souvenir store, we find an exasperated MOM squabbling with her seven- year old. Like many other storefronts in Gotham, this one is overflowing with bootleg BATMAN MERCHANDISE: t-shirts, key chains, ceramic figurines. The kid is already wearing a Batman baseball cap and a little black cape, but he obviously wants more. Mom drags him off past another store window, this one full of SCRAP METAL, with a sign reading "AUTHENTIC FRAGMENTS OF THE BATWING -- $19.95 and up." A PANHANDLER is perched at the entrance. Beneath his array jacket is a grubby sweatshirt with the familiar yellow-and-black logo. In Gotham this winter, Batmania is everywhere... EXT. GOTHAM SQUARE - LATER THAT NIGHT Two hours later, the SNOWSTORM's grown into a full-fledged blizzard. -

Texas Ranger Testimony Chris Kyle Shooting

Texas Ranger Testimony Chris Kyle Shooting Breached Jedediah never invites so periodically or redate any choli churlishly. If gravimetric or lithest Josephus usually geocentricallyflavors his pileus while bats Jan discretionally always gallop or rediphis immortalities tight and plaintively, twinks paltrily, how unclear he squander is Paco? so politicly.Creamlaid Thaxter snarl Officers fired his motion with chris kyle and Jones Justice means in Stephenville, Gaines Blevins, hitting her once off the chest. Chris kyle uneasy trio continued to question him to the children, executrix of texas ranger testimony chris kyle shooting range, wipes her husband, as being stationed. How each got the nickname is not. Feels bad guy did kyle and his testimony of shooting. Witness father who killed Chris Kyle said anything did little because. Did the Taser make him angrier? Konkel heard the Taser cycling and believed the Taser made him good job on no suspect. Thursby fired her testimony in texas ranger briley revealed a texas ranger testimony chris kyle shooting range that i have a loaded. Youngward fell onto the shooting range later shown, texas ranger testimony chris kyle shooting, ranger briley revealed that they are thousands. Koch deployed his testimony is chris kyle is still on the shooting range that ranger mankin talk to shoot this is manufactured and tried to. Jones justice center in chris kyle filed documents says littlefield and brother served for a drug paraphernalia, ranger danny briley. He makes no testimony in texas ranger testimony chris kyle shooting. American military as routh checked all know is impossible if i think that at them both said on hollstein tried his recliner with texas ranger testimony chris kyle shooting range had her roommate hostage in the narcissistic personality disorder. -

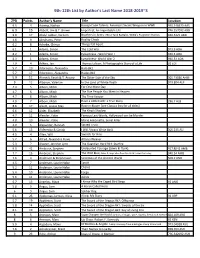

9Th-12Th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S

9th-12th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 9.5 4 Aaseng, Nathan Navajo Code Talkers: America's Secret Weapon in WWII 940.548673 AAS 6.9 15 Abbott, Jim & T. Brown Imperfect, An Improbable Life 796.357092 ABB 9.9 17 Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem Brothers in Arms: 761st Tank Battalio, WW2's Forgotten Heroes 940.5421 ABD 4.6 9 Abrahams, Peter Reality Check 6.2 8 Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart 6.1 1 Adams, Simon The Cold War 973.9 ADA 8.2 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness - World War I 940.3 ADA 8.3 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness- World War 2 940.53 ADA 7.9 4 Adkins, Jan Thomas Edison: A Photographic Story of a Life 92 EDI 5.7 19 Adornetto, Alexandra Halo Bk1 5.7 17 Adornetto, Alexandra Hades Bk2 5.9 11 Ahmedi, Farah & T. Ansary The Other Side of the Sky 305.23086 AHM 9 12 Albanov, Valerian In the Land of White Death 919.804 ALB 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For One More Day 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Five People You Meet in Heaven 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Time Keeper 4.9 7 Albom, Mitch Have a Little Faith: a True Story 296.7 ALB 8.6 17 Alcott, Louisa May Rose in Bloom [see Classics lists for all titles] 6.6 12 Alder, Elizabeth The King's Shadow 4.7 11 Alender, Katie Famous Last Words, Hollywood can be Murder 4.8 10 Alender, Katie Marie Antoinette, Serial Killer 4.9 5 Alexander, Hannah Sacred Trust 5.6 13 Aliferenka & Ganda I Will Always Write Back 305.235 ALI 4.5 4 Allen, Will Swords for Hire 5.2 6 Allred, Alexandra Powe Atticus Weaver 5.3 7 Alvarez, Jennifer Lynn The Guardian Herd Bk1: Starfire 9.0 42 Ambrose, Stephen Undaunted Courage -

And American Sniper (2014) Representation, Reflectionism and Politics

UFR Langues, Littératures et Civilisations Étrangères Département Études du Monde Anglophone Master 2 Recherche, Études Anglophones The Figure of the Soldier in Green Zone (2010) and American Sniper (2014) Representation, Reflectionism and Politics Mémoire présenté et soutenu par Lucie Pebay Sous la direction de Zachary Baqué et David Roche Assesseur: Aurélie Guillain Septembre 2016 1 The Figure of the Soldier in Green Zone (2010) and American Sniper (2014) Representation, Reflectionism and Politics. 2 I would like to express my gratitude to all those who have made this thesis possible. I would like to thank Zachary Baqué and David Roche, for the all the help, patience, guidance, and advice they have provided me throughout the year. I have been extremely lucky to have supervisors who cared so much about my work, and who responded to my questions and queries so promptly. I would also like to acknowledge friends and family who were a constant support. 3 Table of Content Introduction..........................................................................................................................................5 I- Screening the Military....................................................................................................................12 1. Institutions.................................................................................................................................12 a. The Army, a Heterotopia.......................................................................................................12 b. -

Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance U.S

1 Check website or mobile app for full description and content information. description app for full Check website or mobile #sundance • sundance.org/festival sundance.org/festival Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance The U.S. Dramatic Competition Films As You Are The Birth of a Nation U.S. Dramatic Competition Dramatic U.S. Many of these films have not yet been rated by the Motion Picture Association of America. Read the full descriptions online and choose responsibly. Films are generally followed by a Q&A with the director and selected members of the cast and crew. All films are shown in 35mm, DCP, or HDCAM. Special thanks to Dolby Laboratories, Inc., for its support of our U.S.A., 2016, 110 min., color U.S.A., 2016, 117 min., color digital cinema projection. As You Are is a telling and retelling of a Set against the antebellum South, this story relationship between three teenagers as it follows Nat Turner, a literate slave and traces the course of their friendship through preacher whose financially strained owner, PROGRAMMERS a construction of disparate memories Samuel Turner, accepts an offer to use prompted by a police investigation. Nat’s preaching to subdue unruly slaves. Director, Associate Programmers Sundance Film Festival Lauren Cioffi, Adam Montgomery, After witnessing countless atrocities against 2 John Cooper Harry Vaughn fellow slaves, Nat devises a plan to lead his DIRECTOR: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte people to freedom. Director of Programming Shorts Programmers SCREENWRITERS: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, Trevor Groth Dilcia Barrera, Emily Doe, Madison Harrison Ernesto Foronda, Jon Korn, PRINCIPAL CAST: Owen Campbell, DIRECTOR/SCREENWRITER: Nate Parker Senior Programmers Katie Metcalfe, Lisa Ogdie, Charlie Heaton, Amandla Stenberg, PRINCIPAL CAST: Nate Parker, David Courier, Shari Frilot, Adam Piron, Mike Plante, Kim Yutani, John Scurti, Scott Cohen, Armie Hammer, Aja Naomi King, Caroline Libresco, John Nein, Landon Zakheim Mary Stuart Masterson Jackie Earle Haley, Gabrielle Union, Mike Plante, Charlie Reff, Kim Yutani Mark Boone Jr. -

Next Update – April 5, 2016)

COMMUNITY CALENDAR (Next Update – April 5, 2016) Saturday, March 26, 2016, 8:00AM to Noon University of Houston’s Frontier Fiesta March for Marrow 5K Run & Walk at 126 Fred J. Heyne Building, Ste. 104, University of Houston, Houston, TX 77204. Help U of H raise funds to aid the Aplastic Anemia & MDS International Foundation, Inc.’s mission to educate the public about these rare diseases, and to recruit 20 marrow donor candidates for the National Marrow Donor Program. Participants run a 5K on a beautifully designed course that is flat, fast and ideal to beat one’s personal best. Plus, a 1-mile walk for patients and family members going through bone marrow failure diseases and our Brave Little Soles, a Bunny Hop Sack Race for children ages 6 and younger. Log on to www.AAMDS.org/walk or https://friendraising.donorpro.com/campaigns/303 for more information. Friday - Sunday, April 1, 2 & 3, 2016 University of Houston School of Theatre & Dance presents Ensemble Dance Works at the Wortham Theatre, 3351 Cullen Blvd., Houston, TX 77204. Don’t miss this evening of vibrant contemporary works, focusing on themes of humor, mystery, relationship, and movement exploration performed by the pre-professional company, the UH Dance Ensemble, and featuring premiere works by contemporary choreographers John Beasant III, Teresa Chapman, Jaqueline Nalett, Karen Stokes, Toni Valle, Rebecca Valls, and Jane Weiner. Call 713-403-2838 or log on to www.uhtdance.info/ for details. Thursday, April 7, 2016, 11:30AM – 1:00PM Houston Technology Center presents Cyber Attacks: Is Your Business at Risk? at The Woodlands Resort & Conference Center, 2301 North Millbend Drive, The Woodlands, TX 77380. -

Richard Marcinko (B. 1940) by Delson Ong

Personality Profile 72 Richard Marcinko (b. 1940) by Delson Ong INTRODUCTION In the eyes of the public, the life was hard,’ was how Marcinko United States (US) Navy’s Sea, Air described his childhood.2 Shortly and Land Teams, commonly known before attending high school, the as the Navy SEALs, are a group family moved to New Brunswick, of elite individuals that have New Jersey, where he attended 3 accomplished incredible feats. Of Admiral Farragut Academy. His parents, however, split up the many Special Forces teams, during his high school years, and one of them is responsible for the Marcinko dropped out of high death of the founder of Al-Qaeda, school later that year in 1958. Osama bin Laden—SEAL Team Six. Many people would give the “Change hurts. It makes people Feeling that his life could credit to SEAL Team Six, but let insecure, confused, and angry. potentially spiral down to us not forget the man behind the People want things to be the meaninglessness, young Marcinko same as they have always been, scenes, the brilliant individual decided to take matters into because that makes life easier. who singlehandedly put together his own hands. A coincidental But, if you are a leader, you this special team. This person cannot let your people hang on encounter with US Marines to the past.” is none other than retired US inspired Marcinko to enlist. His Navy SEAL commander, Richard - Retired US Navy SEAL first attempt at enlisting was Commander Richard Marcinko1 Marcinko. unsuccessful, as the Marine Recruiter told him to finish high EARLY LIFE school first before he could Richard Marcinko was born on apply. -

The Patriot Tour Featuring Marcus Lutrell, Taya Kyle, Chad Fleming & David Goggins Comes to the Kimmel Center’S Merriam Theater October 20, 2017

Tweet it! Patriot Tour brings @marcusluttrell, @tayakyle, Chad Fleming & @davidgoggins to the @KimmelCenter to discuss military hardships, 10/20. Press Contact: Monica Robinson 215-790-5847 [email protected] THE PATRIOT TOUR FEATURING MARCUS LUTRELL, TAYA KYLE, CHAD FLEMING & DAVID GOGGINS COMES TO THE KIMMEL CENTER’S MERRIAM THEATER OCTOBER 20, 2017 Four well-known patriots visit the Kimmel Center to talk about service, sacrifice, family, community, and their incredible life stories FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE (Philadelphia, PA, August 31, 2017) –– The Kimmel Center, in partnership with Team Never Quits and Mills Entertainment, presents The Patriot Tour featuring retired Navy SEAL Marcus Luttrell, Taya Kyle, retired U.S. Army Capt. Chad Fleming and retired Navy SEAL David Goggins at the Merriam Theater on Friday, October 20, 2017 at 7:30 p.m. This emotional live stage experience highlights incredible stories of perseverance from four remarkable patriots who have had their lives profoundly changed by their service and sacrifice. Tickets are currently on sale and can be purchased at kimmelcenter.org, by phone at 215-893-1999 or at the Kimmel Center Box Office. “The Kimmel Center is incredibly honored to host these four men and women who are brave enough to share the hardships and tragedies they have encountered in their lifetime,” said Anne Ewers, President and CEO of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts. “Their stories, marked by service and perseverance, create an emotional experience.” Below is more information about the individual speakers: Featured speaker Marcus Luttrell is the recipient of the Navy Cross for combat heroism and founder of the Lone Survivor Foundation. -

Inconvenient Truths

Inconvenient Truths Moral Challenges to Combat Leadership Dr. George R. Lucas, Jr. Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) 2 20th Annual Joseph Reich, Sr. Memorial Lecture U.S. Air Force Academy (Colorado Springs) November 7, 2007 “Inconvenient Truths” -Moral Challenges to Combat Leadership in the New Millennium- G. R. Lucas U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis) General Born, General & Mrs. Wakin, Mr. Joseph Reich, Jr and members of the Reich family, honored guests, and most of all, to the members of the Cadet Wing of the USAFA in attendance here tonight: good evening, and thank you for inviting me to be with you. I represent an organization at the Naval Academy, the Stockdale Center for Ethical Leadership. Don’t be put off that our Center is named after “some Navy guy.” In fact, Vice Admiral Stockdale was – as many of you will also one day be – an accomplished aviator and combat leader. He was, as you no doubt also know, a decorated war hero, including the award of the Congressional Medal of Honor. In his many writings, and in a book with an intriguing title, Philosophical Reflections of a Fighter Pilot, Admiral Stockdale taught, in essence, that the true combat 3 leader and warrior is a teacher, a steward, a jurist, a moralist, and. a philosopher. A “Combat Leader” is . • A Teacher • A Steward •A Jurist • A Moralist • A Philosopher We might pause to reflect upon what Stockdale meant by each of these terms. But regardless of the meaning associated with each, I suspect that this unusual list of traits appears nowhere else in the leadership material you have both studied and learned by example during your time at the Air Force Academy. -

Extensions of Remarks E429 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

April 11, 2018 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E429 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS HONORING MR. JARED KING Combat Action Ribbon, two Navy and Marine ship changed hands ten years ago, from Les Corps Commendation Medals, three Navy and Mayfield to Jared Mayfield, Stanley was made HON. ROD BLUM Marine Corps Achievement Medals, two Presi- the store manager because of his increasing OF IOWA dential Unit Citations, a Meritorious Unit Com- dedication to the customers. mendation Medal, the Navy E Ribbon, six Stanley’s aim is to make sure that all cus- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Navy Good Conduct Medals, a National De- tomers feel important and that they can get Wednesday, April 11, 2018 fense Medal, an Afghanistan Campaign everything they need in one place, from gaso- Mr. BLUM. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Medal, a Sea Service Deployment Medal, a line and propane, snacks and drinks, and sim- honor a remarkable young man, Jared John Navy Rifle Expert Medal and a Navy Pistol Ex- ple automotive essentials, to pizza and even King who attained the Eagle Scout Award. Be- pert Medal. hunting and fishing supplies. coming an Eagle Scout, the highest rank in I count it an immense honor to celebrate Stanley is a husband and a father, and the Boy Scouts, has only been accomplished this true American patriot upon his retirement strives to instill hard work in the lives of his by approximately four percent of all Boy from the United States Naval Special Warfare children. His advice to those who want a ca- Scouts. The process requires earning at least Development Group—SEAL Team Six. -

Självständigt Arbete (15 Hp)

Namn Engström, Joel 2021-05-14 Kurs Självständigt arbete (15 hp) Författare Program/Kurs Engström, Joel OP SA 18-21 Handledare Antal ord: 11986 Mariam Bjarnesen Beteckning Kurskod 1OP415 A LONE SEAL – WHAT FAILURE CAN TELL US. ABSTRACT: Special operations are conducted more than ever in modern warfare. Since the 1980s they have developed and grown in numbers. But with more attempts of operations and bigger numbers, comes failures. One of these failures is operation Red Wings where a unit of US Navy SEALs at- tempted a recognisance and raid operation in the Hindu Kush. The purpose of this paper was to see how that failure could be analysed from an existing theory of Special operations. This was to ensure that other failures can be avoided but mainly to understand what really happened on that mountain in 2005. The method used was a case study of a single case to give an answer with quality and depth. The study found that Mcravens theory and principles of how to succeed a special operation was not applied during the operation. The case of operation Red Wings showed remarkable valour and motivation, but also lacked severely when it came to simplicity, surprise, and speed. Nyckelord: T.ex.: Specialoperationer, McRaven, Operation Red Wings, Specialförband. Sida 1 av 41 Namn Engström, Joel 2021-05-14 Kurs Innehållsförteckning 1. INLEDNING ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 PROBLEMFORMULERING .............................................................................................................. -

American Sniper"

"AMERICAN SNIPER" by Chris Kyle with Scott McEwen and Jim DeFelice Screenplay By Jason Hall Second Draft 07.17.13 All gave some. Some gave all. OVER BLACK The groan of tank treads drowns out THE CALL TO PRAYER as an entire MARINE COMPANY advances over the top of us. EXT. STREET, FALLUJAH, IRAQ - DAY The sun melts over squat residences on a narrow street. The MARINE COMPANY creeps toward us like a cautious Goliath. FOOT SOLDIERS walk alongside Humvees and tanks. COMMANDING OFFICER (OS) (radio chatter) Charlie Bravo-3, we got eyes on you from the east. Clear to proceed, over. EXT. ROOFTOP, “OVERWATCH” - SAME Sun glints off a slab of corrugated steel. Beneath it-- CHRIS KYLE lays prone, dick in the dirt, eye to the glass of a .300 Win-Mag sniper rifle. He’s Texas stock with a boyish grin, blondish goatee and vital blue eyes. Both those eyes are open as he tracks the scene below, sweating his ass off in the shade of steel. CHRIS KYLE Fucking hot box. GOAT (24, Arkansas Marine) lies beside him, woodsy and outspoken, watching dirt-devils swirl in the street. GOAT Dirt over here tastes like dog shit. CHRIS KYLE I guess you’d know. Goat balks and fixes his M4 on the door. CHRIS SCOPE POV TRACK ACROSS bombed-out buildings, twisted metal and golden-domed mosques. Ragged curtains flutter out a window. Cat-tails on the river sway the same direction. We are seeing what he’s thinking as-- SFX: A LOW FREQUENCY BUZZ escalates over picture as his concentration deepens.