The Norman Doorways at Wordwell and West Stow Churches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role Description LVNB Team Vicar 50% Fte 2019

Role description signed off by: Archdeacon of Sudbury Date: April 2019 To be reviewed 6 months after commencement of the appointment, and at each Ministerial Development Review, alongside the setting of objectives. 1 Details of post Role title Team Vicar 50% fte, held in plurality with Priest in Charge 50% fte Barrow Benefice Name of benefices Lark Valley & North Bury Team (LVNB) Deanery Thingoe Archdeaconry Sudbury Initial point of contact on terms of Archdeacon of Sudbury service 2 Role purpose General To share with the Bishop and the Team Rector both in the cure of souls and in responsibility, under God, for growing the Kingdom. To ensure that the church communities in the benefice flourish and engage positively with ‘Growing in God’ and the Diocesan Vision and Strategy. To work having regard to the calling and responsibilities of the clergy as described in the Canons, the Ordinal, the Code of Professional Conduct for the Clergy and other relevant legislation. To collaborate within the deanery both in current mission and ministry and, through the deanery plan, in such reshaping of ministry as resources and opportunities may require. To attend Deanery Chapter and Deanery Synod and to play a full part in the wider life of the deanery. To work with the ordained and lay colleagues as set out in their individual role descriptions and work agreements, and to ensure that, where relevant, they have working agreements which are reviewed. This involves discerning and developing the gifts and ministries of all members of the congregations. To work with the PCCs towards the development of the local church as described in the benefice profile, and to review those needs with them. -

WSC Planning Decisions 43/19

PLANNING AND REGULATORY SERVICES DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 25/10/2019 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/15/2298/FUL Planning Application - (i) Extension and Village Hall DECISION: alterations to Hopton Village Hall (ii) Thelnetham Road Approve Application Doctor's surgery and associated car Hopton DECISION TYPE: parking and the modification of the existing Suffolk Committee vehicular access onto Thelnetham Road IP22 2QY ISSUED DATED: (iii) residential development of 37 24 Oct 2019 dwellings (including 11 affordable housing WARD: Barningham units) and associated public open space PARISH: Hopton Cum including a new village green, Knettishall landscaping,ancillary works and creation of new vehicular access onto Bury Road APPLICANT: Pigeon Investment Management AGENT: Evolution Town Planning LLP - Mr David Barker DC/18/0628/HYB Hybrid Planning Application - 1. Full Former White House Stud, DECISION: Planning Application - (i) Horse racing White Lodge Stables Refuse Application industry facility (including workers Warren Road DECISION TYPE: dwelling) and (ii) new access (following Herringswell Delegated demolition of existing buildings to the CB8 7QP ISSUED DATED: south of the site) 2. Outline Planning 22 Oct 2019 Application (Means of Access to be WARD: Iceni considered) (i) up to 100no. dwellings and PARISH: Herringswell (ii) new access (following demolition of existing buildings to the north of the site and the existing dwelling known as White Lodge Bungalow). APPLICANT: Hill Residential Ltd AGENT: Mrs Meghan Bonner - KWA Architects (Cambridge) Ltd Planning and Regulatory Services, West Suffolk Council, West Suffolk House, Western Way, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, IP33 3YU DC/19/0235/FUL Planning Application - 2no. -

Breckland Warrens

The INTERNAL ARCHAEOLOGY of the BRECKLAND WARRENS A Report by The Breckland Society © Text, layout and use of all images in this publication: The Breckland Society 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright holder. Text written by Anne Mason with James Parry. Editing by Liz Dittner. Front cover: Drawing of Thetford Warren Lodge by Thomas Martin, 1740 © Thetford Ancient House Museum, Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service. Dr William Stukeley had travelled through the Brecks earlier that century and in his Itinerarium Curiosum of 1724 wrote of “An ocean of sand, scarce a tree to be seen for miles or a house, except a warrener’s here and there.” Designed by Duncan McLintock. Printed by SPC Printers Ltd, Thetford. The INTERNAL ARCHAEOLOGY of the BRECKLAND WARRENS A Report by The Breckland Society 2017 1842 map of Beachamwell Warren. © Norfolk Record Office. THE INTERNAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE BRECKLAND WARRENS Contents Introduction . 4 1. Context and Background . 7 2. Warren Banks and Enclosures . 10 3. Sites of the Warren Lodges . 24 4. The Social History of the Warrens and Warreners . 29 Appendix: Reed Fen Lodge, a ‘new’ lodge site . 35 Bibliography and credits . 39 There is none who deeme their houses well-seated who have nott to the same belonging a commonwalth of coneys, nor can he be deemed a good housekeeper that hath nott a plenty of these at all times to furnish his table. -

Typed By: Apb Computer Name: LTP020

PLANNING AND REGULATORY SERVICES DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 03/07/2020 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/20/0714/OUT Outline Planning Application (Means of Street Farm DECISION: Access to be considered) - 4no. dwellings Low Street Refuse Application and associated garages Bardwell DECISION TYPE: IP31 1AR Delegated APPLICANT: Mr J Webber - RR Webber & ISSUED DATED: Son 1 Jul 2020 WARD: Bardwell AGENT: Mr D Rogers-ALA Ltd PARISH: Bardwell DC/20/0692/HH Householder Planning Application - Single 8 Bury Road DECISION: storey rear extension (previous application Barrow Approve Application DC/17/2643/HH) IP29 5DE DECISION TYPE: Delegated APPLICANT: Mr Michael Sparkes ISSUED DATED: 1 Jul 2020 WARD: Barrow PARISH: Barrow Cum Denham DC/20/0823/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - Barton Hall DECISION: 1no. Beech (T001 on plan) fell The Street No Objections Barton Mills DECISION TYPE: APPLICANT: Mr & Mrs John Hughes Suffolk Delegated IP28 6AW ISSUED DATED: AGENT: Miss Naomi Hull - Temple Property 1 Jul 2020 And Construction WARD: Manor PARISH: Barton Mills DC/20/0835/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - The Dhoon DECISION: 1no. Cherry (T1 on plan) reduce in height 19 The Street No Objections by up to 3 metres and reduce lateral Barton Mills DECISION TYPE: spread by up to 2 metres IP28 6AA Delegated ISSUED DATED: APPLICANT: Cottrell 1 Jul 2020 WARD: Manor AGENT: Mr Luke Wickens PARISH: Barton Mills Planning and Regulatory Services, West Suffolk Council, West Suffolk House, Western Way, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, IP33 3YU DC/20/0620/FUL Planning Application - 1no. -

Bury St Edmunds May 2018

May 2018 BURY ST EDMUNDS RESPOND INSPECTOR MATT DEE Police in Bury St Edmunds are currently investigating a series of Exposure offences that have taken place in the area of Moreton Hall. Offences have occurred on the 29th March, 22nd April, 3rd May and 6th May in the late afternoon. The offender is sometimes using a black and white bike and is described as either mixed race or tanned skinned male, aged late 20's to early 30's and short dark brown hair. Any witnesses or anyone with information are urged to come forward. MAKING YOUR COMMUNITY SAFER The SNT have attended a number of initiatives over the past month giving crime prevention advice and reassurance at different venues. PCSO Pooley attended a Fraud awareness day at Barclays bank, offering advice on keeping your bank account and personal finances safe. PCSO Howell attended Beetons Lodge, offering advice on personal safety and security. PCSO Chivers attended the first 'Meet up Monday' event at The Boosch Bar, a new initiative set up to lend a friendly ear to anyone FUTURE EVENTS vulnerable, lonely or even new to the area. The future events that your SNT are involved in, and will give you an opportunity to chat to them to raise your concerns are: PREVENTING, REDUCING AND SOLVING CRIME AND ASB 9th May - Great Whelnetham Parish PC Fox has investigated a series of three theft of peddle cycles meeting that were left insecure outside one of our town Upper schools. 10th May - Fornahm St Martin Parish Having reviewed the CCTV, the suspects were identified and meeting 13th May - South Suffolk Show offenders have all been caught. -

Bury St Edmunds

October 2017 BURY ST EDMUNDS RESPOND INSPECTOR MATT DEE On 29th September 2017 Bury St Edmunds Police responded to a large Fire at Cylce King, Bury St Edmunds. We worked with our colleagues from the fire service to evacuate the area, close the roads and secure the arrests of two males, on suspicion of Arson. In the aftermath of the fire we worked with our partners from the fire service and St Edmundsbury Borough Council to secure evidence, make the area safe, offering support to local businesses affected by the fire and to re-open the road as soon as possible to cause minimum disruption to the local community. MAKING YOUR COMMUNITY SAFER Bury SNT executed a drugs warrant in Rougham, after receiving and developing some community intelligence. 18 Cannabis Plants and growing equipment were seized, and a male was arrested for Cultivation of Cannabis. Bury SNT and Emergency Service Cadets assisted with the St Nicholas Hospice charity 'Girls Night Out', where over 2,500 ladies took to the FUTURE EVENTS street of the town in a sponsored walk, providing support and The future events that your SNT are reassurance to all involved. involved in, and will give you an opportunity to chat to them to raise your concerns are PREVENTING, REDUCING AND SOLVING CRIME AND ASB 9th October - PC Ellis will be at Lackford Bury SNT have been working in partnership with Havebury Housing Association to Parish Council meeting 7.30 pm, Lackford combat anti-social behaviour in Greene Road, BSE that has had a detrimental effect Church to the quality of lives of the local residents. -

WSC Planning Applications 22/20

LIST 22 29 MAY 2020 Applications Registered between 25 – 29 May 2020 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk. Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Note: Representations on Brownfield Permission in Principle applications and/or associated Technical Details Consent applications must arrive not later than 14 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/20/0800/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - (i) The Mill VALID DATE: Mixed species hedge row (H2 on plan) Old Mill Lane 28.05.2020 reduce height to 2 metres above ground Barton Mills level, and reduce sides by 0.75 metres (ii) IP28 6AS EXPIRY DATE: 1no. Weeping Willow (T1 on plan) - overall 09.07.2020 crown reduction by up to 3 metres GRID REF: WARD: Manor APPLICANT: Mr D Scott 572593 273850 PARISH: Barton Mills AGENT: Mr Paul Goldsmith - Green Wood Tree Surgery CASE OFFICER: Falcon Saunders DC/20/0823/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - Barton Hall VALID DATE: 1no. Beech (T001 on plan) fell The Street 22.05.2020 Barton Mills APPLICANT: Mr & Mrs John Hughes Suffolk EXPIRY DATE: IP28 6AW 03.07.2020 AGENT: Miss Naomi Hull - Temple Property And Construction WARD: Manor CASE OFFICER: Falcon Saunders GRID REF: PARISH: Barton Mills 571827 273953 DC/20/0835/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - The Dhoon VALID DATE: 1no. -

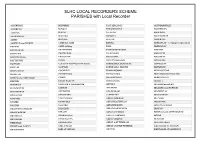

SLHC LOCAL RECORDERS SCHEME PARISHES with Local Recorder

SLHC LOCAL RECORDERS SCHEME PARISHES with Local Recorder ALDEBURGH BRUNDISH EAST BERGHOLT GRUNDISBURGH ALDERTON BUNGAY EDWARDSTONE HACHESTON AMPTON BURGH ELLOUGH HADLEIGH ASHBOCKING BURSTALL ERISWELL HALESWORTH ASHBY BUXHALL EUSTON HARGRAVE ASHFIELD cum THORPE CAMPSEA ASHE EXNING HARKSTEAD - Looking for replacement BACTON CAPEL St Mary EYKE HARLESTON BADINGHAM CHATTISHAM FAKENHAM MAGNA HARTEST BARNHAM CHEDBURGH FALKENHAM HASKETON BARTON MILLS CHEDISTON FELIXSTOWE HAUGHLEY BATTISFORD CLARE FLIXTON (Lowestoft) HAVERHILL BAWDSEY CLAYDON with WHITTON RURAL FORNHAM St. GENEVIEVE HAWKEDON BECCLES CLOPTON FORNHAM St. MARTIN HAWSTEAD BEDINGFIELD COCKFIELD FRAMLINGHAM HEMINGSTONE BELSTEAD CODDENHAM FRECKENHAM HENSTEAD WITH HULVER BENHALL & STERNFIELD COMBS FRESSINGFIELD HERRINGFLEET BENTLEY CONEY WESTON FROSTENDEN HESSETT BLAXHALL COPDOCK & WASHBROOK GIPPING HIGHAM (near BURY) BLUNDESTON CORTON GISLEHAM HIGHAM ( near IPSWICH) BLYTHBURGH COVEHITHE GISLINGHAM HINDERCLAY BOTESDALE CRANSFORD GLEMSFORD HINTLESHAM BOXFORD CRETINGHAM GREAT ASHFIELD HITCHAM BOXTED CROWFIELD GREAT BLAKENHAM HOLBROOK BOYTON CULFORD GREAT BRADLEY HOLTON ST MARY BRADFIELD COMBUST DARSHAM GREAT FINBOROUGH HOPTON BRAISEWORTH DEBACH GREAT GLEMHAM HORHAM with ATHELINGTON BRAMFIELD DENHAM (Eye) GREAT LIVERMERE HOXNE BRAMFORD DENNINGTON GREAT SAXHAM HUNSTON BREDFIELD DRINKSTONE GREAT & LT THURLOW HUNTINGFIELD BROME with OAKLEY EARL SOHAM GREAT & LITTLE WENHAM ILKETSHALL ST ANDREW BROMESWELL EARL STONHAM GROTON ILKETSHALL ST LAWRENCE SLHC LOCAL RECORDERS SCHEME PARISHES with Local -

SEBC Planning Applications 19/17

LIST 19 5 May 2017 Applications Registered between 01/05/17 – 05/05/17 ST. EDMUNDSBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk . Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/17/0824/VAR Planning application - variation of conditions Washington VALID DATE: 5 (access) and 8 (turning and parking on Quaker Lane 20.04.2017 site) of DC/16/0414/FUL to enable easy and Bardwell safe egress and access to the site for the 2 Suffolk EXPIRY DATE: No dwellings and vehicular access following IP31 1AL 15.06.2017 demolition of existing dwelling WARD: Bardwell APPLICANT: McNeill-Parker Homes AGENT: Stour Valley Design GRID REF: PARISH: Bardwell 594323 273637 CASE OFFICER: Gary Hancox DC/17/0661/HH Householder Planning Application - 35 Out Risbygate VALID DATE: Temporary wooden steps & handrail to Bury St Edmunds 03.05.2017 create disabled access IP33 3RJ EXPIRY DATE: APPLICANT: Mrs Margaret Scoulding 28.06.2017 AGENT: Mr Paul Crascall - P & P PROPERTY GRID REF: MAINTAINANCE 584395 264477 WARD: Risbygate CASE OFFICER: Matthew Gee PARISH: Bury St Edmunds Town Council (EMAIL) DC/17/0703/FUL Planning Application - Two storey rear Langton House VALID DATE: extension to create 1no. -

SEBC Planning Decisions 50/17

ST EDMUNDSBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING AND GROWTH DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 08/12/2017 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/17/2237/HH Householder Planning Application - (i) Tamarisk DECISION: Single storey side extension including 4 Barrow Hill Approve Application attached garage (demolition of existing Barrow DECISION TYPE: garage) (ii) Replacement of existing flat IP29 5DX Committee roof over rear extension with pitched roof ISSUED DATED: 8 Dec 2017 APPLICANT: Mr Chris Rawlings WARD: Barrow PARISH: Barrow Cum Denham DC/17/1387/HH Householder Planning Application - Coldham Hall DECISION: Replacement private treatment plant (of Coldham Hall Lane Approve Application existing dilapidated system) Stanningfield DECISION TYPE: Bury St Edmunds Delegated APPLICANT: Mr And Mrs M Vaughn Suffolk ISSUED DATED: IP29 4SD 4 Dec 2017 AGENT: Dean Jay Pearce Architectural WARD: Rougham Design PARISH: Bradfield Combust With Stanningfield DC/16/1689/FUL Planning Application - 4 no. flats and Land Adj To 1 Abbots Gate DECISION: associated car parking. Abbots Gate Withdrawn/ Abandoned Bury St Edmunds DECISION TYPE: APPLICANT: Mr & Mrs Youngman Suffolk ISSUED DATED: AGENT: Paul Scarlett - Brown And Scarlett 7 Dec 2017 Ltd WARD: Southgate PARISH: Bury St Edmunds Town Council DC/16/2490/ADV Application for Advertisement Consent - Dog And Partridge DECISION: Replacement signage to include (i) 3no non 29 Crown Street Withdrawn/ Abandoned illuminated amenity signs, (ii) 2no double Bury St Edmunds DECISION TYPE: sided externally illuminated hanging signs, Suffolk Deferred (iii) 1no non illuminated car park sign and IP33 1QU ISSUED DATED: (iv) 2no non illuminated wall mounted 8 Dec 2017 fascia signs. -

Ancient Monuments in Suffolk L

208 SUFFOLK INSTITUTE OF ARCH/EOLOGY Ancient Monumentsin Suffolk. The followingis a list of Ancient Monuments in Suffolkwhich have been scheduledby the Ministry of Public Building and Works under the Acts of 1913-1953since ° .c.. the last list was printed in ifolume xxvi Part 3 for 1954, page 233ofthese Proceedings.Membersare again urged to report promptly to Officersof the Institute any damage or threat of damage to thesemonumentswhich may come to their notice.--Editor. Burial Mounds RomanRemains Chillesford, round barrow E. of Coddenham, Baylham Roman site. Chillesford Walks. Long Melford, Roman villa at Chillesford, two round barrows on Liston Lane. Wantisden Heath. A Pakenham, Roman camp N. of Culford, Hill of Health, round barrow. Pakenham Windmill. Eriswell, Dale Hole, round barrow. Foxhall, Pole Hill, round barrow on Brightwell Heath. EcclesiasticalBuildings Gazeley, Pin Farm, round barrow. Dunwich, chapel of St. James's Herringswell, Shooting Lodge Planta- Hospital. tion, round barrow. Flixton Priory. Higham, round barrow 400 yds. S.W. Little Welnetham, remains of circular of Desning Lodge. chapel E. of church. Icklingham, five round barrows near Mendham Priory. Bernersfield Farm. Sibton Abbey. Icklingham, How Hill, round barrow. Sudbury, St. Bartholomew's Chapel. Iken, round barrow on Iken Heath. Wenhaston, St. Margaret's Chapel, Kentford, Pin Farm, round barrow. Mells. Knettishall, two round barrows on Hut Hill and in Brick-kiln Covert. Levington, eight round barrows on Castles Levington Heath. Martlesham, two round barrows W. Bawdsey, martello tower (No. 3) S.E. of Foxburrow Plantation. of Buckanay Farm. Bawdsey, martello tower (No. 4) by Martlesham, eight round barrows on Martlesham Heath. Bawdsey Beach. -

Oak Lodge, Mill Road, Hengrave, Item 19 PDF 565 KB

Issue No. 17. Oak Lodge, Mill Road, Hengrave Area or Boundary between Culford, Fornham St Martin cum St Genevieve Properties and Hengrave in vicinity of Mill Road Under Review Parishes Culford Fornham St Martin cum Fornham St Genevieve Hengrave Borough Fornham Wards Risby County Thingoe North Division Method of Letter to directly affected residents Consultation Letter to stakeholders Projected Three electors in Oak Lodge and Annexe to Oak Lodge. The impact electorate on parishes is minimal. and consequential impacts Analysis Two of the parish councils have responded confirming they are both of the view that the property should be in Fornham St Genevieve. The electors are of the view that their property should be in Hengrave. As the property in question is currently in Culford parish, the Working Party will need to consider whether a change of boundary is required, and if it is, whether the property should be included in Fornham St Genevieve or Hengrave parishes. Summary of comments received during Phase 1 A. Response of Fornham St Martin cum Fornham St Genevieve Parish Council Fornham St Martin cum Fornham St Genevieve Parish Council have consulted with Culford, West Stow and Wordwell Parish Council and are of the view that Oak Lodge should be in Fornham St Genevieve parish. The reason being that this property is directly adjacent to properties already in the parish and that such a change will result in a more cohesive community and enable more effective and convenient delivery of local services. B. Response of Culford, West Stow and Wordwell Parish Council Culford, West Stow and Wordwell Parish Council have consulted with Fornham St Martin cum Fornham St Genevieve Parish Council and are of the view that Oak Lodge should be in Fornham St Genevieve parish.