Examining Long-Range Transport of Montrose Dde Via Marine Mammals: Evaluating Risks to California Condors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUMMER 2018 Mprpd.Org Preserving and Protecting Parks and Open

SUMMER 2018 mprpd.org Monterey Peninsula Regional Park District LET’S GO CELEBRATING 10 YEARS! OUTDOORS! Your adventure activities guide for all ages Preserving and Protecting Parks and Open Space AMessagefromtheGeneralManager Dear Friends, The greatest challenges sometimes create the greatest opportunities, resulting in the greatest outcomes. Such was the case when private land owners, the community, The Trust for Public Land, Santa Lucia Conservancy (SLC), Trout Unlimited, Welcome State of California, County of Monterey, Monterey Peninsula Regional Park District (MPRPD), and others combined their vision and work to create the Rancho Cañada unit of Palo Corona Regional Park from the former Rancho Cañada Golf Club. In April, The Trust for Public Land transferred ownership of the property to the residents and visitors of the Central Coast. SLC Executive Director Christy Fischer stated, “From the beginning, this project has been about a community coming together around a shared vision.” MPRPD’s acquisition of Rancho Cañada will facilitate one of the nation’s most significant environmental and cultural resource restoration, preservation and conservation projects. “As this new parkland is restored to improve the health and future of our river, native plants and wildlife, I hope it will also be a place where visitors can learn about and celebrate the ways and wisdom of its first people. It is a great gift to us all.” - Linda Yamane, Rumsen Ohlone Tribal historian “The land had been in our family since the late 1800s. Protecting the land and preserving it for future generations is my family’s way of showing tribute to my great-grandfather, William Hatton. -

Record of Decision

Record of Decision United States Department of Agriculture Strategic Community Fuelbreak Forest Service Improvement Project November 2018 Los Padres National Forest, Monterey Ranger District, Monterey County, California CONTENTS DECISION ……………………………………..…………………………………............. 1 BACKGROUND………………………………………………………………………….. 2 DECISION RATIONALE……………………………………………………………….. 3 Relevant Law Policy, and Land Management Plan Direction…………………………… 3 Community Protection…………………………………………………………………….5 Health and Safety during Implementation………………………………………………...5 Resource Protection……………………………………………………………………….6 Use of Herbicide…………………………………………………………………………..6 How Alternative 4 meets Purpose and Need……………………………………………... 6 How Alternative 4 Responds to the Significant Issues…………………………………... 7 Other Factors Considered………………………………………………………………… 8 Staying Effective Over Time Through Monitoring……………………………………… 8 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT………………………………………………………………. 8 ALTERNATIVES CONSIDERED……………………………………………………… 9 Environmentally Preferred Alternative………………………………………………….. 10 FINDINGS REQUIRED BY OTHER LAWS AND REGULATIONS………………. 10 National Forest Management Act………………………………………………………… 10 Endangered Species Act………………………………………………………………….. 11 Migratory Bird Treaty Act……………………………………………………………….. 11 Wilderness Act…………………………………………………………………………… 11 Clean Water Act………………………………………………………………………….. 11 National Historic Preservation Act………………………………………………………. 11 Environmental Justice……………………………………………………………………. 11 ADMINISTRATIVE REVIEW………………………………...………………………... 11 IMPLEMENTATION DATE …………………………………………………………… -

Big Sur for Other Uses, See Big Sur (Disambiguation)

www.caseylucius.com [email protected] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Big Sur For other uses, see Big Sur (disambiguation). Big Sur is a lightly populated region of the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries, many definitions of the area include the 90 miles (140 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County,[1][2] and extend about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. Other sources limit the eastern border to the coastal flanks of these mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland. Another practical definition of the region is the segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel south to San Simeon. The northern end of Big Sur is about 120 miles (190 km) south of San Francisco, and the southern end is approximately 245 miles (394 km) northwest of Los Angeles. The name "Big Sur" is derived from the original Spanish-language "el sur grande", meaning "the big south", or from "el país grande del sur", "the big country of the south". This name refers to its location south of the city of Monterey.[3] The terrain offers stunning views, making Big Sur a popular tourist destination. Big Sur's Cone Peak is the highest coastal mountain in the contiguous 48 states, ascending nearly a mile (5,155 feet/1571 m) above sea level, only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[4] The name Big Sur can also specifically refer to any of the small settlements in the region, including Posts, Lucia and Gorda; mail sent to most areas within the region must be addressed "Big Sur".[5] It also holds thousands of marathons each year. -

Must Road Trips

Must PHOTO COURTESY OF SEEMONTERY.COM OF COURTESY PHOTO Bixby Creek Bridge Monterey LoveRoad Trips Carmel-by-the-Sea Our writer’s romantic getaway gone Big Sur wrong leads to a revelation along Pfeiffer Beach California’s Highway 1. McWay Falls By Alan Rider Lucia Gorda Ragged Point McWay Falls in Monterey County is visible from COURTESY OF SEEMONTEREY.COM California’s Highway 1. San Simeon Cambria hey say that the road to true love is filled with in hand and weather forecasts promising sunny skies and pull over somewhere safe if you want to snap pics), and on ups and downs. Here’s proof that that’s no mere balmy temperatures, I had no choice but to go on one of to Andrew Molera State Park. There, I met up with the folks aphorism. the world’s most romantic road trips solo (sad face). from the Ventana Wildlife Society for a four-hour excursion TYou see, my most recent romantic interest—let’s call Pulling out of the parking lot of the oceanfront Sanctuary to locate endangered California condors in the wild. Using her Wendy because that’s her name—and I were brought Beach Resort in Monterey that first morning, I found running a radio-tracking antenna and a spotting scope, our guide together by our mutual love of road trips. Her online dating the Miata RF’s six-speed manual through the gears to be gave us a rare look at these gigantic birds that are slowly but profile made clear she was thoroughly into them, and I’m surprisingly therapeutic. -

Carmel Pine Cone, September 24, 2007

Folksinging Principal honored May I offer you legend plays for athletics, a damp shoe? Sunset Center academics — INSIDE THIS WEEK BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID CARMEL, CA Permit No. 149 Volume 93 No. 38 On the Internet: www.carmelpinecone.com September 21-27, 2007 Y OUR S OURCE F OR L OCAL N EWS, ARTS AND O PINION S INCE 1915 Pot bust, gunfire Ready for GPU may thwart at Garland Park her closeup ... Rancho Cañada By MARY BROWNFIELD housing project FIVE MEN suspected of a cultivating marijuana near Garland Park were arrested at gunpoint late By KELLY NIX Monday morning in the park’s parking lot following a night of strange occurrences that included gunfire, a THE AFFORDABLE housing “overlay” at the mouth of chase and hikers trying to flag down motorists at mid- Carmel Valley outlined in the newly revised county general night on Carmel Valley Road, according to Monterey plan could jeopardize the area’s most promising affordable County Sheriff’s Deputy Tim Krebs. housing development, its backers contend. The saga began Sunday afternoon, when a pair of The Rancho Cañada Village project, a vision of the late hikers saw two men with duffle bags and weapons walk Nick Lombardo, would provide 281 homes at the mouth of out of a nearby canyon. Afraid, one of the hikers yelled, Carmel Valley, constructed on land which is part of the “Police!” prompting the men to drop the bags and run, Rancho Cañada golf course. according to Krebs. According to the plan, half the homes would be sold at The duffles were full of freshly cut marijuana, market prices, subsidizing the which the hikers decided to take, according to the sher- other half, which would be iff’s department. -

California Condor (Gymnogyps Californianus) 5-Year Review

California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Southwest Region June 2013 Acknowledgement: The Service gratefully acknowledges the commitment and efforts of the California Condor Recovery Program partners for their many on-going contributions towards condor recovery. Our partners were instrumental both in ensuring that we used the best available science to craft our analyses and recommendations in this 5-year review and in providing individual feedback that was used to refine this document. Photo Credit: Unless otherwise indicated, all photos, charts, and graphs are products of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Page | 2 5-YEAR REVIEW California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) I. GENERAL INFORMATION Purpose of 5-Year Reviews: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is required by section 4(c)(2) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act) to conduct a status review of each listed species at least once every 5 years. The purpose of a 5-year review is to evaluate whether or not the species’ status has changed since it was listed (or since the most recent 5-year review). Based on the 5- year review, we recommend whether the species should be removed from the Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife, changed in status from endangered to threatened, or changed in status from threatened to endangered. Our original listing as endangered or threatened is based on the species’ status considering the five threat factors described in section 4(a)(1) of the Act. These same five factors are considered in any subsequent reclassification or delisting decisions. -

Strategic Community Fuelbreak Improvement Project Final Environmental Impact Statement

Final Environmental United States Department of Impact Statement Agriculture Forest Service Strategic Community Fuelbreak May 2018 Improvement Project Monterey Ranger District, Los Padres National Forest, Monterey County, California In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

Monarch Butterfly Micro-Climate Project

Microclimate parameters associated with three overwintering monarch butterfly habitats in central California: a four year study Project Report 2006 Winters 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 Study Sites: Andrew Molera State Park (Stands A and B) Point Lobos State Reserve Ventana Wildlife Society Conservation Ecology Program By: Jessica L. Griffiths1 1 E-mail: [email protected]; Phone: (831) 624-1202 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……………………………………………………………………………... 1 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………. 2 Results…………………………………………………………………………………... 4 Discussion………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Literature Cited………………………………………………………………………...…8 List of Tables Table 1. Microclimate parameters compared during winter 2005-06 between the two groves at Andrew Molera State Park (Stand A and Stand B) and the grove at Point Lobos State Reserve, Monterey County, California..………………….........…..................................….....9 Table 2. Sunlight intensity (lumens/sq. m) compared over four winters from 2002 to 2006 between the two groves at Andrew Molera State Park (Stand A and Stand B) and the grove at Point Lobos State Reserve, Monterey County, California…………………………........9 Table 3. Temperature (˚C) compared over four winters from 2002 to 2006 between the two groves at Andrew Molera State Park (Stand A and Stand B) and the grove at Point Lobos State Reserve, Monterey County, California……………………………………………...9 Table 4. Relative humidity (%) compared over four winters from 2002 to 2006 between the two groves at Andrew Molera State Park (Stand A and Stand B) and the grove at Point Lobos State Reserve, Monterey County, California……………………………………...10 Table 5. Dew point (˚C) compared over four winters from 2002 to 2006 between the two groves at Andrew Molera State Park (Stand A and Stand B) and the grove at Point Lobos State Reserve, Monterey County, California……………………………………………..10 List of Figures Figure 1. -

Carmel Pine Cone, December 9, 2011

GIFT GUIDE A SPECIAL SECTION INSIDE THIS WEEK’S PAPER – DECEMBER 9, 2011 Volume 97 No. 49 On the Internet: www.carmelpinecone.com December 9-15, 2011 Y OUR S OURCE F OR L OCAL N EWS, ARTS AND O PINION S INCE 1915 County and city Heavy winds wreak havoc down the coast to collaborate on By CHRIS COUNTS nesses. “I’ve never experienced anything like this,” said Martha one-way Scenic Road WINDS GUSTING to 50 MPH blew through Big Sur Karstens, chief of the Big Sur Volunteer Fire Brigade. “It’s a late last week, killing a condor researcher, sparking four mess down here. The wind was howling like a freight train.” small fires and causing extensive damage to homes and busi- Mike Tyner, 35, was killed Wednesday, Nov. 30, at about By MARY SCHLEY 3 p.m. when high winds caused a branch to fall on him. Tyner, who served as a field super- THE COUNTY’S most notorious hairpin curve is about visor for the Ventana Wildlife Society’s condor to become a lot safer as Monterey County moves ahead with recovery program, was traveling along the plans to make Scenic Road one-way around Carmel Point. Coast Ridge Road near Marble Peak when part The switch, from the city limits to Carmel River State of a large oak tree snapped and landed on his Beach, should help relieve traffic jams, make walking and vehicle. Shortly before he was killed, Tyner bicycling safer, and preserve the bluffs — not to mention was monitoring the progress of a young con- reduce the likelihood somebody will drive off the edge. -

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan DRAFT FOR REVIEW ONLY June 2020 Prepared by: Beyond Green Travel Table of Contents Acknowledgements............................................................................................. 3 Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 About Beyond Green Travel ................................................................................ 9 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 10 Vision and Methodology ................................................................................... 16 History of Tourism in Big Sur ............................................................................. 18 Big Sur Plans: A Legacy to Build On ................................................................... 25 Big Sur Stakeholder Concerns and Survey Results .............................................. 37 The Path Forward: DSP Recommendations ....................................................... 46 Funding the Recommendations ........................................................................ 48 Highway 1 Visitor Traffic Management .............................................................. 56 Rethinking the Big Sur Visitor Attraction Experience ......................................... 59 Where are the Restrooms? -

Santiago Fire

Basin-Indians Fire Basin Complex CA-LPF-001691 Indians Fire CA-LPF-001491 State Emergency Assessment Team (SEAT) Report DRAFT Affecting Watersheds in Monterey County California Table of Contents Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………… Team Members ………………………………………………………………………… Contacts ………………………………………………………..…………………….… Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….. Summary of Technical Reports ……………………………………..………………. Draft Technical Reports ……………………………………………………..…………..…… Geology ……………………………………………………………………...……….… Hydrology ………………………………………………………………………………. Soils …………………………………………………………………………………….. Wildlife ………………………………………………………………….………………. Botany …………………………………………………………………………………... Marine Resources/Fisheries ………………………………………………………….. Cultural Resources ………………………………………………………..…………… List of Appendices ……………………………………………………………………………… Hazard Location Summary Sheet ……………………………………………………. Burn Soil Severity Map ………………………………………………………………… Land Ownership Map ……………………………………………………..…………... Contact List …………………………………………………………………………….. Risk to Lives and Property Maps ……………………………………….…………….. STATE EMERGENCY ASSESSMENT TEAM (SEAT) REPORT The scope of the assessment and the information contained in this report should not be construed to be either comprehensive or conclusive, or to address all possible impacts that might be ascribed to the fire effect. Post fire effects in each area are unique and subject to a variety of physical and climatic factors which cannot be accurately predicted. The information in this report was developed from cursory field -

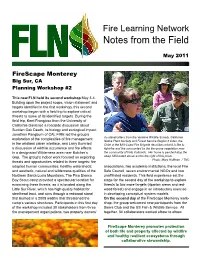

Notes from the Field

Fire Learning Network Notes from the Field May 2011 FireScape Monterey Big Sur, CA Planning Workshop #2 This new FLN held its second workshop May 3-4. Building upon the project scope, vision statement and targets identified in the first workshop, this second workshop began with a field trip to explore critical threats to some of its identified targets. During the field trip, Kerri Frangioso from the University of California-Davis led a roadside discussion about Sudden Oak Death, its biology and ecological impact. Jonathan Pangburn of CAL FIRE led the group’s As stakeholders from the Ventana Wildlife Society, California exploration of the complexities of fire management Native Plant Sociiety and Forest Service Region 5 listen, the in the wildland urban interface, and Larry Born led Chief of the Mid-Coast Fire Brigade describes what it is like to a discussion of wildfire occurrence and fire effects fight fire and live surrounded by the fire-prone vegetation near in a designated Wilderness area near Botcher’s the community of Palo Colorado. Her home is perched atop the Gap. The group’s indoor work focused on exploring steep hill located above and to the right of this photo. Photo: Mary Huffman / TNC threats and opportunities related to three targets: fire adapted human communities; healthy watersheds; associations, two academic institutions, the local Fire and aesthetic, natural and wilderness qualities of the Safe Council, seven environmental NGOs and two Northern Santa Lucia Mountains. The Pico Blanco unaffiliated residents. This field experience set the Boy Scout camp provided a spectacular location for stage for the second day of the workshop to explore examining these threats, as it is located along the threats to two more targets (riparian areas and red- Little Sur River, which has high quality habitat for wood forest) and engage in an introductory exercise steelhead trout, and runs through a redwood stand in developing conceptual system models.