Strategic Community Fuelbreak Improvement Project Final Environmental Impact Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

Grooming Veterinary Pet Guidelines Doggie Dining

PET GUIDELINES GROOMING VETERINARY We welcome you and your furry companions to Ventana Big Sur! In an effort to ensure the peace and tranquility of all guests, we ask for your PET FOOD EXPRESS MONTEREY PENINSULA assistance with the following: 204 Mid Valley Shopping VETERINARY EMERGENCY & Carmel, CA SPECIALTY CENTER A non-refundable, $150 one-time fee per pet 831-622-9999 20 Lower Ragsdale Drive will be charged to your guestroom/suite. Do-it-yourself pet wash Suite 150 Monterey, CA Pets must be leashed at all times while on property. 831.373.7374 24 hours, weekends and holidays Pets are restricted from the following areas: Pool or pool areas The Sur House dining room Spa Alila Organic garden Owners must be present, or the pet removed from the room, for housekeeping to freshen your guestroom/suite. If necessary, owners will be required to interrupt activities to attend to a barking dog that may be disrupting other guests. Our concierge is happy to help you arrange pet sitting through a local vendor (see back page) if desired. These guidelines are per county health codes; the only exceptions are for certified guide dogs. DOGGIE DINING We want all of our guests to have unforgettable dining experiences at Ventana—so we created gourmet meals for our furry friends, too! Available 7 a.m. to 10 p.m through In Room Dining or at Sur House. Chicken & Rice $12 Organic Chicken Breast / Fresh Garden Vegetables / Basmati Rice Coco Patty $12 Naturally Raised Ground Beef / Potato / Garden Vegetables Salmon Bowl $14 Salmon / Basmati Rice / Sweet Potato -

BSMAAC MCRMA Report 030519

PROJECT APPLICATIONS IN BIG SUR County of Monterey Resource Management Agency – Planning ACTIVITY BETWEEN OCTOBER 5, 2018 AND FEBRUARY 25, 2019 The following projects are currently active within the Big Sur Coast Land Use Plan area or have been decided since OCTOBER 5, 2018. Changes are highlighted: FILE # APPLICANT AREA PROPOSED USE PLN190049 VITA ROBERT A AND 36918 PALO FOLLOW‐UP COASTAL DEVELOPMENT PERMIT OF AN PREVIOUSLY APPROVED EMERGENCY (PLANNER: LIZ JENNIE G CO‐TRS COLORADO ROAD, PERMIT (PLN170270) TO ALLOW AN 11‐MILE BIG SUR MARATHON RACE TIED TO THE GONZALES) (GRIMES RANCH CARMEL ANNUAL BIG SUR INTERNATIONAL MARATHON. THIS RACE CONSISTS OF APPROXIMATELY RACE) 1,600 PARTICIPANTS ON THE GRIMES RANCH WHICH IS LOCATED ON THE EAST SIDE OF HIGHWAY 1, CARMEL (ASSESSOR'S PARCEL NUMBER 243‐262‐006‐000), SOUTH OF PALO COLORADO ROAD, BIG SUR COAST LAND USE PLAN, COASTAL ZONE. APPLIED ON FEBRUARY 11, 2019; 30‐DAY REVIEW PERIOD ENDS ON MARCH 13, 2019. STATUS IS “APPLIED”. PLN190043 ROBERTS BRYAN & 37600 HIGHWAY 1, EMERGENCY COASTAL DEVELOPMENT PERMIT TO ALLOW CONSTRUCTION OF A 128 (PLANNER: ADRIENNE D TRS MONTEREY LINEAR FOOT HILFIKER RETAINING WALL TO SECURE HILLSIDE FOR ACCESS; DUE TO RICHARD “CRAIG” HILLSIDE SUPPORTING SINGLE FAMILY DWELLING FAILING AND LEAKING SEPTIC TANK. SMITH) THE PROPERTY IS LOCATED AT 37600 HIGHWAY 1, BIG SUR (ASSESSORS PARCEL NUMBER 418‐111‐012‐000), BIG SUR COAST LAND USE PLAN, COASTAL ZONE. APPLIED ON FEBRUARY 6, 2019. PLANNER WORKING WITH APPLICANT & COASTAL COMMISSION STAFF ON MINIMUM NECESSARY TO STABILIZE. STATUS IS “APPLIED”. PLN190032 GORDA OCEAN FRONT 72801 HIGHWAY 1, EMERGENCY COASTAL DEVELOPMENT PERMIT FOR THE REPAIR OF AN AREA SUBJECT TO (PLANNER: PROPERTIES INC BIG SUR SUPERFICIAL SLIDING AND EROSION DUE TO WEAK SOILS SATURATED BY RAINFALL AND RICHARD “CRAIG” SUBSURFACE SEEPAGE. -

Carmel Pine Cone, June 17, 2011 (Main News)

InYour A CELEBRATION OF THE C ARMEL LIFESTYLE… D A SPECIAL SECTIONreams… INSIDE THIS WEEK! Volume 97 No. 24 On the Internet: www.carmelpinecone.com June 17-23, 2011 Y OUR S OURCE F OR L OCAL N EWS, ARTS AND O PINION S INCE 1915 BIG SUR MEN PLEAD Monterey activist sues over C.V. senior housing GUILTY IN 2009 DUI ■ Wants occupancy curtailed to save amount which wasn’t allocated and which the Peninsula does not have, Leeper said. By MARY BROWNFIELD water; developer says limits will be met Leeper is a well known local activist and protester on numerous subjects. A May 8, 2008, commentary by fellow IN A deal struck with prosecutors that would keep them By PAUL MILLER from getting maximum sentences, Big Sur residents Mark activist Gordon Smith in Monterey County Weekly accused Hudson, 51, and Christopher Tindall, 30, pleaded guilty to CITING THE danger to the availability of water for vehicular manslaughter while intoxicated and hit-and-run other developments in the Monterey Peninsula and potential See LAWSUIT page 28A resulting in death Monday in environmental damage to the Monterey County Superior Carmel River if a senior housing Court. project at the mouth of Carmel Deputy district attorney Valley is allowed to open at full Doug Matheson said Hudson capacity, Monterey activist Ed will receive a five-year Leeper is asking a judge to issue an prison sentence, while emergency order that the facility, Tindall’s sentence could be Cottages of Carmel, be limited to probation, or up to four years 56 beds. -

1933 .'.',MI!H'ii, !!I3i!L!!Iwmic'

A C aliforria \"Jlnter S}Jortll 'Ttl~mv"" State Ilnute -37 ~ Auburn to lj·uckE'e .... Official Journal of the Department of PublicCWorks JAN.-FEB. State of Californi ct; 1933 .'.',MI!H'ii, !!i3I!l!!IWmIC' Table of Contents Pae;e Highway Budget Projects for Next Biennium Total $61,700,000______ 1 IIighway Dollar Spreading to 50,000 Californians Through 12,000 Workers 2 By Morgan Keaton, Assistant Deputy DIrector ot Public Works Illustrations of Highway Improvements by Relief QllOta Crews_______ 3 Piru Creek Moyed Into ew Concrete ChanIleL_____________________ 4 By R. C. My"r~, Assistant Engineer, Dist. VII Channel Change Operations Pictured . 5 Snow Removal Pays Dividends to Motorists and State________________ 6 By T. H. Dennis, Maintenance Engineer Scenes of Snow Removal Operations_______ 7 Dr. W. W. Barham Appointed Highway ommissioner-IlJustrated __ _ 8 Gasoline Tax Revenues Continue Downward Trend-Illustrated______ 9 ational State Highway Body Confirms Value of Relief Work 10 By George T. McCoy, Principal Assistant Engineer Highway and Parks Depa.rtments Saving Coast Areas 12 By Wm. E. Colby Chairman, California Sta.te Park Commission Views of Recently Acquired Coast Park 13 $100,000 U. S. Participation Approved for Ri er Bank Protection 14 By R. L. Jones, Deputy State Engineer Eight Major IIighway Projects Advertised 16 Tabulation of December Highway Projeets________________ _ 17 Facsimile of Unique New Years Greeting 19 Labor Gets 91 Pel' Cent of Every $1,000 for Concrete Paving 20 Report of State Engineer on Water Resources 25 Water Applications and Permits 28-29 Vital Statisti('.<J on Dam ControL ._____________________ 30 Details of Projects in 1933-35 Biennial Budget. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 ONE Official Record of Adoption................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000............................................................ 1-1 1.2 Adoption By Local Governing Bodies and Supporting Documentation ..................................................................................... 1-1 Section 2 TWO Plan Description...................................................................................................................2-1 Section 3 THREE Community Description......................................................................................................3-1 3.1 Location, Geography, and History ........................................................ 3-1 3.2 Demographics ...................................................................................... 3-1 3.3 Land Use and Development Trends ...................................................... 3-2 3.4 Incorporated Communities.................................................................... 3-2 Section 4 FOUR Planning Process.................................................................................................................4-1 4.1 Overview of Planning Process .............................................................. 4-1 4.2 Hazard Mitigation Planning Team........................................................ 4-2 4.2.1 Formation of the Planning Team............................................... 4-2 4.2.2 Planning Team -

Garrapata State Park Initial Study Mitigated Negative Declaration Draft

COASTAL HABITAT RESTORATION AND COASTAL TRAIL IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Garrapata State Park Initial Study Mitigated Negative Declaration Draft State of California Department of Parks and Recreation Monterey District June 13, 2012 This page intentionally blank. COASTAL HABITAT RESTORATION AND COASTAL TRAIL IMPROVEMENT PROJECT IS/MND – DRAFT JUNE 2012 GARRAPATA STATE PARK CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION AND PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................ 1 CHAPTER II ENVIRONMENTAL CHECKLIST...................................................... 13 I. AESTHETICS. ................................................................................ 17 II. AGRICULTURE AND FORESTRY RESOURCES ...……………… 21 III. AIR QUALITY.................................................................................. 23 IV. BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES .......................................................... 26 V. CULTURAL RESOURCES ............................................................. 48 VI. GEOLOGY AND SOILS .................................................................. 64 VII. GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS ................................................. 69 VIII. HAZARDS AND HAZARDOUS MATERIALS ................................. 70 IX. HYDROLOGY AND WATER QUALITY .......................................... 73 X. LAND USE AND PLANNING .......................................................... 78 XI. MINERAL -

UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer

UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer Photographs - Job Number Index Description Job Number Date Thompson Lawn 1350 1946 August Peter Thatcher 1467 undated Villa Moderne, Taylor and Vial - Carmel 1645-1951 1948 Telephone Building 1843 1949 Abrego House 1866 undated Abrasive Tools - Bob Gilmore 2014, 2015 1950 Inn at Del Monte, J.C. Warnecke. Mark Thomas 2579 1955 Adachi Florists 2834 1957 Becks - interiors 2874 1961 Nicholas Ten Broek 2878 1961 Portraits 1573 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1517 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1573 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1581 circa 1945-1960 Portraits 1873 circa 1945-1960 Portraits unnumbered circa 1945-1960 [Naval Radio Training School, Monterey] unnumbered circa 1945-1950 [Men in Hardhats - Sign reads, "Hitler Asked for It! Free Labor is Building the Reply"] unnumbered circa 1945-1950 CZ [Crown Zellerbach] Building - Sonoma 81510 1959 May C.Z. - SOM 81552 1959 September C.Z. - SOM 81561 1959 September Crown Zellerbach Bldg. 81680 1960 California and Chicago: landscapes and urban scenes unnumbered circa 1945-1960 Spain 85343 1957-1958 Fleurville, France 85344 1957 Berardi fountain & water clock, Rome 85347 1980 Conciliazione fountain, Rome 84154 1980 Ferraioli fountain, Rome 84158 1980 La Galea fountain, in Vatican, Rome 84160 1980 Leone de Vaticano fountain (RR station), Rome 84163 1980 Mascherone in Vaticano fountain, Rome 84167 1980 Pantheon fountain, Rome 84179 1980 1 UCSC Special Collections and Archives MS 6 Morley Baer Photographs - Job Number Index Quatre Fountain, Rome 84186 1980 Torlonai -

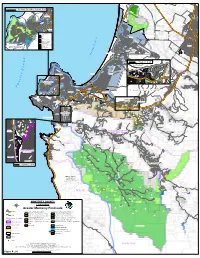

·|}Þ183 40 R Le D 17-Mi

40 0 2,500 Feet Del Monte Forest Non - Coastal - Detail ·|}þ183 40 R LE D 17-MI LAPIS RD C O 40 N G R E SH S PACIFIC GROVE I B S AN A P S Y R D R NASHUA RD D 40 DEL MONTE BLVD 17-MILE DR ·|}þ68 DAVID AVE 40 40 SLOAT RD OCEAN RD MONTEREY 40 ¤£101 MC FADDEN RD GMP-1.9 ST Legend for Del Monte Forest Coastal Zone Bondary Parcel Æ` COOPER RD City Limits MARINA ARMSTRONG RD y Residential BLANCO RD RESIDENTIAL 2 Units/Acre RESERVATION RD Marina Municipal Forest Lake a Airport STEVENSON DR RESIDENTIAL 2.4 Units/Acre 1 Greater Salinas BIRD ROCK RD ·|}þ RESIDENTIAL 4 Units/Acre B Resource Conservation S a y l Resource Conservation 10 Ac Min in a s R SALINAS i Land use within the Coastal Zone is Open Space Forest e v e r addressed in the Del Monte Forest LUP. Open Space Recreation r IMJIN RD Urban Reserve e HITCHCOCK RD t n o Fort Ord Dunes State Park INTERGARRISON RD M 1ST ST HITCHCOCK RD DAVIS RD n GIGLING RD a 0 2,000 Feet Pasadera - Detail FOSTER RD e See the Fort Ord Master Plan for this area, Fig LU6a. c LIGHTHOUSE AVE SOUTH BOUNDARY RD 2.5 2.76 YORK RD EUCALYPTUS RD ERA DR SAD O GENERAL JIM MOORE BLV A SPRECKELS BLVD ESTRELLA AVE P 2.76 68 c SAND CITY SEASIDE YORK RD 2.76 ·|}þ PACIFIC GROVE Laguna Seca Recreation Area R IVER RD i .76 .76 10 f DAVID AVE i 5.1 68 5.1 10 ·|}þ 10 c BIT RD 5.1 Del Monte Forest See Detail 5.1 a DEL MONTE AVE P ·|}þ218 FREMONT ST FREMONT ST See Fort Ord Master Plan for this area, Fig LU6a. -

Carmel Pine Cone, September 24, 2007

Folksinging Principal honored May I offer you legend plays for athletics, a damp shoe? Sunset Center academics — INSIDE THIS WEEK BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID CARMEL, CA Permit No. 149 Volume 93 No. 38 On the Internet: www.carmelpinecone.com September 21-27, 2007 Y OUR S OURCE F OR L OCAL N EWS, ARTS AND O PINION S INCE 1915 Pot bust, gunfire Ready for GPU may thwart at Garland Park her closeup ... Rancho Cañada By MARY BROWNFIELD housing project FIVE MEN suspected of a cultivating marijuana near Garland Park were arrested at gunpoint late By KELLY NIX Monday morning in the park’s parking lot following a night of strange occurrences that included gunfire, a THE AFFORDABLE housing “overlay” at the mouth of chase and hikers trying to flag down motorists at mid- Carmel Valley outlined in the newly revised county general night on Carmel Valley Road, according to Monterey plan could jeopardize the area’s most promising affordable County Sheriff’s Deputy Tim Krebs. housing development, its backers contend. The saga began Sunday afternoon, when a pair of The Rancho Cañada Village project, a vision of the late hikers saw two men with duffle bags and weapons walk Nick Lombardo, would provide 281 homes at the mouth of out of a nearby canyon. Afraid, one of the hikers yelled, Carmel Valley, constructed on land which is part of the “Police!” prompting the men to drop the bags and run, Rancho Cañada golf course. according to Krebs. According to the plan, half the homes would be sold at The duffles were full of freshly cut marijuana, market prices, subsidizing the which the hikers decided to take, according to the sher- other half, which would be iff’s department. -

Coastal Management Accomplishments in the Big Sur Coast Area

CCC Hearing Item: Th 13.3 February 9, 2012 _______________________________________________________________ California Coastal Commission’s 40th Anniversary Report Coastal Management in Big Sur History and Accomplishments Gorda NORTHERN BIG SUR Gorda NORTHERN BIG SUR CENTRAL BIG SUR Gorda NORTHERN BIG SUR CENTRAL BIG SUR SOUTHERN BIG SUR Gorda “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, southbound, north of Soberanes Point. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, at Cape San Martin, Big Sur Coast. CCRP#1649 9/2/2002 “A Highway Runs Through It” Heading south on Highway One. “A Highway Runs Through It” Southbound Highway One, near Partington Point. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, south of Mill Creek. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Historic Big Creek Bridge, at entrance to U.C. Big Creek Reserve. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, looking south to the coastal terrace at Pacific Valley. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 “A Highway Runs Through It” Highway One, at Monterey County line, looking south into San Luis Obispo County, with Ragged Point and Piedras Blancas in far distance (on the right). ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 NORTHERN BIG SUR “Grand Entrance View” (from the north) of the Big Sur Coast, looking southwards to Soberanes Point, with Point Sur in the distance (on the horizon to the right). ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 Garrapata State Park/Beach, looking north to Soberanes Point. ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 Mouth of Garrapata Creek (from Highway One). ©Kelly Cuffe 2012 Sign for Rocky Point Restaurant, with Notley’s Landing and Rocky Creek Bridge in distance. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below.