Adaptive Risk Governance Processes in Rural Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Groundwater Oxygen Isotope Anomaly Before the M6.6 Tottori Earthquake

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Groundwater oxygen isotope anomaly before the M6.6 Tottori earthquake in Southwest Japan Received: 13 December 2017 Satoki Onda1, Yuji Sano 1, Naoto Takahata 1, Takanori Kagoshima1, Toshihiro Miyajima1, Accepted: 8 March 2018 Tomo Shibata2, Daniele L. Pinti 3, Tefang Lan4, Nak Kyu Kim5, Minoru Kusakabe5 & Published: xx xx xxxx Yoshiro Nishio6 Geochemical monitoring of groundwater in seismically-active regions has been carried out since 1970s. Precursors were well documented, but often criticized for anecdotal or fragmentary signals, and for lacking a clear physico-chemical explanation for these anomalies. Here we report – as potential seismic precursor – oxygen isotopic ratio anomalies of +0.24‰ relative to the local background measured in groundwater, a few months before the Tottori earthquake (M 6.6) in Southwest Japan. Samples were deep groundwater located 5 km west of the epicenter, packed in bottles and distributed as drinking water between September 2015 and July 2017, a time frame which covers the pre- and post-event. Small but substantial increase of 0.07‰ was observed soon after the earthquake. Laboratory crushing experiments of aquifer rock aimed to simulating rock deformation under strain and tensile stresses were carried out. Measured helium degassing from the rock and 18O-shift suggest that the co-seismic oxygen anomalies are directly related to volumetric strain changes. The fndings provide a plausible physico- chemical basis to explain geochemical anomalies in water and may be useful in future earthquake prediction research. Hydro-geochemical precursors of major earthquakes have attracted the attention of researchers worldwide, because they are not entirely unexpected1,2. -

Ffe

JP9950127 ®n m&?. mti HBA\ /j^¥ m** f «ffe#«i^p^fe«j:y f^± (top-soii) frbzarm (sub-son) '\<Dm$tm*wfeLtz0 i37 ,37 ®mmm(nmij\c£^ffi'Pi-& cs(DfrMim%¥mmmm7^mT\ ££>c cs<z)fe , i3, !^«££1ffiIELfc&JK0*£«fc^«'> tS Cs<Dn<Dffi8¥tmffil*4l~-42Spk%-3tz0 ffi^f.^CTi'N© 137Cs©*»4^iMf^±fc*)1.6~1.7%/^-C&o^o £fc* 1996^K t3, &\fZ Cs<Dft±£*<DTm<D%ttm&*mfeLfcm%\*¥ftX-6:4t1i-it:0 Residence half-time of 137Cs in the top-soils of Japanese paddy and upland fields Misako KOMAMURA, Akito TSUMURA*. Kiyoshi K0DA1RA** National Institute of Agro-Environmental Sciences, *ex-National Institute of Agro-Environmental Sciences, **Prof. Em. Ashikaga Institute of Technology A series of top-soil samples of 14 paddy fields and 10 upland fields in Japan, were annually collected during more than 30 years, to be examined in the contents of ,37Cs. The data, which were obtained by the use of a gamma spectrometric system, received some statistical treatments to distinguish the annual decline of 137Cs contents from deviations. Then the authors calculated "residence half-time of137Cs" within top-soil, and "eluviation rate of 137Cs" from top to the sub-layer of the soil. The following nationwide results were obtained irrespective of paddy or upland fields: (1) The "apparent residence half-time" was estimated as 16—-17 years. This one consists of both effects of eluviation and nuclear disintegration. (2) The "true residence half-time" was reported as 41~~42 years. This one depends on the eluviation speed of 137Cs exclusively, because the influence of nuclear disinte• gration has been compensated. -

China Russia

1 1 1 1 Acheng 3 Lesozavodsk 3 4 4 0 Didao Jixi 5 0 5 Shuangcheng Shangzhi Link? ou ? ? ? ? Hengshan ? 5 SEA OF 5 4 4 Yushu Wuchang OKHOTSK Dehui Mudanjiang Shulan Dalnegorsk Nongan Hailin Jiutai Jishu CHINA Kavalerovo Jilin Jiaohe Changchun RUSSIA Dunhua Uglekamensk HOKKAIDOO Panshi Huadian Tumen Partizansk Sapporo Hunchun Vladivostok Liaoyuan Chaoyang Longjing Yanji Nahodka Meihekou Helong Hunjiang Najin Badaojiang Tong Hua Hyesan Kanggye Aomori Kimchaek AOMORI ? ? 0 AKITA 0 4 DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S 4 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Akita Morioka IWATE SEA O F Pyongyang GULF OF KOREA JAPAN Nampo YAMAJGATAA PAN Yamagata MIYAGI Sendai Haeju Niigata Euijeongbu Chuncheon Bucheon Seoul NIIGATA Weonju Incheon Anyang ISIKAWA ChechonREPUBLIC OF HUKUSIMA Suweon KOREA TOTIGI Cheonan Chungju Toyama Cheongju Kanazawa GUNMA IBARAKI TOYAMA PACIFIC OCEAN Nagano Mito Andong Maebashi Daejeon Fukui NAGANO Kunsan Daegu Pohang HUKUI SAITAMA Taegu YAMANASI TOOKYOO YELLOW Ulsan Tottori GIFU Tokyo Matsue Gifu Kofu Chiba SEA TOTTORI Kawasaki KANAGAWA Kwangju Masan KYOOTO Yokohama Pusan SIMANE Nagoya KANAGAWA TIBA ? HYOOGO Kyoto SIGA SIZUOKA ? 5 Suncheon Chinhae 5 3 Otsu AITI 3 OKAYAMA Kobe Nara Shizuoka Yeosu HIROSIMA Okayama Tsu KAGAWA HYOOGO Hiroshima OOSAKA Osaka MIE YAMAGUTI OOSAKA Yamaguchi Takamatsu WAKAYAMA NARA JAPAN Tokushima Wakayama TOKUSIMA Matsuyama National Capital Fukuoka HUKUOKA WAKAYAMA Jeju EHIME Provincial Capital Cheju Oita Kochi SAGA KOOTI City, town EAST CHINA Saga OOITA Major Airport SEA NAGASAKI Kumamoto Roads Nagasaki KUMAMOTO Railroad Lake MIYAZAKI River, lake JAPAN KAGOSIMA Miyazaki International Boundary Provincial Boundary Kagoshima 0 12.5 25 50 75 100 Kilometers Miles 0 10 20 40 60 80 ? ? ? ? 0 5 0 5 3 3 4 4 1 1 1 1 The boundaries and names show n and t he designations us ed on this map do not imply of ficial endors ement or acceptance by the United N at ions. -

Justice and Humanity JCG - Keeping the Oceans Safe and Enjoyable for Future Generations! 120°E 130°E 140°E 150°E 160°E 170°E

Justice and Humanity JCG - Keeping the oceans safe and enjoyable for future generations! 120°E 130°E 140°E 150°E 160°E 170°E Territorial sea 165° East Approx. 430,000 km2 (Including inland waters) 5 0 °N Territorial sea + EEZ Approx. 4,470,000 km2 (Japan’s Land area x 12) Etorofu Island Land area Japan Sea 2 Approx. 380,000 km 4 0 °N Takeshima Pacific Ocean Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) 2 East China Sea Approx. 4,050,000 km 3 0 °N Senkaku Islands Ogasawara Islands Io To Island Yonagunijima Island Minami-Tori Shima Island 2 0 °N Oki-no-Tori Shima Island 17° North Extended continental shelves* Japan's search responsibility area Approx. 180,000 km2 under the U.S.-Japan SAR Agreement * Areas of the sea as defined in Article 2 (2) of the Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf Act. For illustration purposes, this map also shows geographical intermediate lines in waters in which borders with neighboring countries have yet to be demarcated. Despite ranking only 61st in the world in terms of land area (380,000 km2), Japan’s territorial waters and exclusive economic zone combined are 12 times larger (4,470,000 km2) than its land area. In December 1986, the Agreement between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan on Maritime Search and Rescue (U.S.-Japan SAR Agreement) was concluded, under which Japan is responsible for coordinating search and rescue activities in the vast expanse of ocean that extends northward from 17° North and westward from 165° East. -

Distributions of a Halophilous and a Riparian Species of Harvestmen Along Sendai River, Tottori City, with the First Records of Harvestmen in Tottori Sand Dunes

Acta Arachnologica, 69 (2): 95–103, December 20, 2020 Distributions of a halophilous and a riparian species of harvestmen along Sendai River, Tottori City, with the first records of harvestmen in Tottori Sand Dunes Nobuo Tsurusaki1, 2*, Minako Kawaguchi2,3, Yamato Funakura2,4, Toru Matsumoto2,5 & Yuito Obae6 1 Laboratory of Animal Taxonomy, Faculty of Agriculture, Tottori University, Tottori 680-8551, Japan 2Department of Regional Environment, Faculty of Regional Sciences, Tottori University, Tottori 680-8551, Japan and 6Faculty of Environmental Studies, Tottori University of Environmental Studies, Wakabadai-kita 1-1-1, 689-1111, Japan E-mail: [email protected], *Corresponding author Abstract ― Distributions of a maritime harvestman, Psathyropus tenuipes and a riparian harvestman Paraum- bogrella pumilio were investigated along the Sendai River, Tottori City, Honshu, Japan. Psathyropus tenuipes was found from the mouth of the river to the site 4 km upstream where slight salinity (0.1 PPT) was detected in the river. On the other hand, no specimens were found from the upstream sites where no salinity was detect- ed. This indicates that the species needs at least a slight salinity for its occurrence. Paraumbogrella pumilio was found at five sites from the dry riverbed near the Shobu floodgate to a site on the right bank of Sendai River just upstream of Yachiyo Bridge. Occurrence of this species seems to be related to presence of open ground covered with lower grasses on the banks. Recently, the both species were also found from the right bank of the river mouth of Sendai River that is also a part of Tottori Sand Dunes. -

By Municipality) (As of March 31, 2020)

The fiber optic broadband service coverage rate in Japan as of March 2020 (by municipality) (As of March 31, 2020) Municipal Coverage rate of fiber optic Prefecture Municipality broadband service code for households (%) 11011 Hokkaido Chuo Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11029 Hokkaido Kita Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11037 Hokkaido Higashi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11045 Hokkaido Shiraishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11053 Hokkaido Toyohira Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11061 Hokkaido Minami Ward, Sapporo City 99.94 11070 Hokkaido Nishi Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11088 Hokkaido Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11096 Hokkaido Teine Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 11100 Hokkaido Kiyota Ward, Sapporo City 100.00 12025 Hokkaido Hakodate City 99.62 12033 Hokkaido Otaru City 100.00 12041 Hokkaido Asahikawa City 99.96 12050 Hokkaido Muroran City 100.00 12068 Hokkaido Kushiro City 99.31 12076 Hokkaido Obihiro City 99.47 12084 Hokkaido Kitami City 98.84 12092 Hokkaido Yubari City 90.24 12106 Hokkaido Iwamizawa City 93.24 12114 Hokkaido Abashiri City 97.29 12122 Hokkaido Rumoi City 97.57 12131 Hokkaido Tomakomai City 100.00 12149 Hokkaido Wakkanai City 99.99 12157 Hokkaido Bibai City 97.86 12165 Hokkaido Ashibetsu City 91.41 12173 Hokkaido Ebetsu City 100.00 12181 Hokkaido Akabira City 97.97 12190 Hokkaido Monbetsu City 94.60 12203 Hokkaido Shibetsu City 90.22 12211 Hokkaido Nayoro City 95.76 12220 Hokkaido Mikasa City 97.08 12238 Hokkaido Nemuro City 100.00 12246 Hokkaido Chitose City 99.32 12254 Hokkaido Takikawa City 100.00 12262 Hokkaido Sunagawa City 99.13 -

![Tottori a Whole New Japan [ Travel Spot Guide ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9289/tottori-a-whole-new-japan-travel-spot-guide-1559289.webp)

Tottori a Whole New Japan [ Travel Spot Guide ]

TOTTORI A WHOLE NEW JAPAN [ TRAVEL SPOT GUIDE ] Tottori. At first, even the name was unfamiliar to me. Little did I know that what awaited me was the adventure of a lifetime full of sights, tastes, moments, and memories that I would treasure forever... Tottori, Uniquely Yours Tottori Official Website Tottori Tourism Guide www.tottori-tour.jp/en/ Facebook Visit Tottori, Japan www.facebook.com/ tottoritouren/ Instagram TOTTORI Awesome www.instagram.com/ tottoriawesome/ Traveling to Tottori Majestic sand dunes shimmer under resplendent Tottori is an 80-minute flight from Tokyo starry skies. Old-growth forests enshroud mountain and a few hours by train from Osaka and sanctuaries long protected as the dwelling place Kyoto. Nestled between the Sea of Japan and the Chugoku Mountains, this region of of gods. Cultural legacies passed down through unparalleled natural beauty blessed with the ages lives on in historical shrines and temples. the fruits of the land and bounty of the sea Sapporo Here, local delicacies prepared with fresh seasonal is an ideal destination for travelers seeking to venture off the beaten path. ingredients punctuate every outdoor adventure. Here, a veritable mountain of unique discoveries awaits. Here, you don’t have to settle for the sights Kyoto Tottori that everyone has already seen. Nagoya Come to Tottori and find a whole new Japan. Fukuoka Tokyo Osaka Hiroshima Tottori The stage is set for your adventure. 2 3 9:00 a.m. Mizuki Shigeru Road Fantastical creatures from Japanese folklore called Yokai will delight children and adults alike at this popular site dedicated to the famous manga artist Mizuki Shigeru. -

Characteristics of Sea-Effect Clouds and Precipitation Over

RESEARC H ARTICLE C haracteristics of Sea ‐Effect Clo uds a nd Precipitatio n 10.1029/2018J D029586 Over t he Sea of Japa n Regio n as Observed Key Poi nts: by A‐Trai n Satellites • The majority of winter clouds and precipitatio n over t he Sea of Japa n Tyler K. West 1 , W. Ja mes Steenburgh1 , and Gerald G. Mace1 regio n occur duri ng sea‐effect p eri o ds 1 Depart ment of At mospheric Sciences, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, U T, US A • T he distributio n of sea effect varies in the region and is modulated by la nd‐sea i nteractio ns, coastli ne geo metry, and orographic effects A b st r a ct Prolific winter ( Dece mber‐January‐February) sno wfall occurs over north west Japan due to • Sea-effect precipitation is shallo wer freq ue nt sea‐effect precipitatio n t hat develops d uri ng cold‐air o utbreaks over t he Sea of Japa n (S OJ). and more co m mon (deeper and less K no wledge of sea ‐effect clouds a nd precipitatio n across t he S OJ regio n has historically bee n co nstrai ned, co m mon) in the northern (southern a nd ce ntral) Sea of Japa n regio n ho wever, by li mited offs hore i n situ observatio ns a nd re mote ‐se nsi ng li mitatio ns. T his paper uses se nsors fro m National Aeronautics and Space Ad ministration ( N AS A)'s A‐Train Satellite Constellation to exa mine wi nter sea ‐effect properties i n t he S OJ regio n. -

Tour Itinerary

GEEO ITINERARY x-JAPAN – Summer Day 1: Tokyo Arrive at any time. On arrival, please check the notice board in the hotel entrance for details of the time and place of the meeting. As fellow group members will be arriving throughout the day, there are no planned activities until the group meeting in the early evening (6:00 p.m. or 7:00 p.m.). After the group meeting, consider heading out for a group dinner. Day 2: Tokyo Take a walking tour of eclectic modern Tokyo from the hub of Shinjuku to Shibuya through to Harajuku. The rest of the day is free for exploring more of the city. Your tour leader will lead the group on a walking tour of eclectic modern Tokyo from the hub of Shinjuku to Shibuya through to Harajuku. The rest of the day is free for exploring more of the city. Day 3: Tokyo/Nagano Journey to Nagano, located in the Japanese Alps and host city of the 1998 Winter Olympics. Visit the world-famous Jigokudani Monkey Park and watch Japanese snow monkeys bathing in the natural hot springs. Today we board a bullet train and journey to Nagano, located in the Japanese Alps and host city of the 1998 Winter Olympics. We will visit the Jigokudani Monkey Park, where wild snow monkeys can be seen bathing in the natural hot springs. The pool where most of the monkeys soak is man-made, fed by the hot springs. Along the walking paths up to the pools other monkeys tend to stop and watch visitors curiously. -

Kumamoto Earthquake Gc Briefing

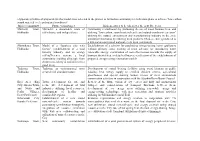

GC BRIEFING An Update from GC Analytics® May 2016 KUMAMOTO EARTHQUAKE In April of 2016, at mid-month, the world was once again reminded of the potential power of seismic activity by a series of earthquakes that hit Kumamoto prefecture on the southernmost island of Japan, as well as by the large shake that occurred half way around the world in Ecuador. In this briefing we summarize the basic facts regarding the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake, including a description of the event itself and the basic seismic background of the area. We also outline the major earthquake coverages provided by Japanese insurers, report on possible loss amounts and list some of the major affected facilities. 1 F-4 | DEPTH OF THE RYUKYU TRENCH AND DEPTH OF HISTORICAL EARTHQUAKES T-1 | EARTHQUAKE EVENTS IN JAPAN STANDARD F-5 | INDUSTRIAL PARKS AND CORPORATIONS IN KUMATOMO PREFECTURE F-1 | EVENTS OF MOMENT MAGNITUDE 6.0 AND LARGER UTC+09 Moment Depth in Epicenter F-3 | EARTHQUAKE INTENSITY BY LOCATION USING MODIFIED MERCALLI INTENSITY UTC+09 Moment Depth in Epicenter Intensity 7.5 Date Time Magnitudekilometers Latitude Longitude Date Time MagnitudekilometersLatitudeLongitude April 14, 2016 21:26:36 (UTC+09) Magnitude 6.2 April 16, 2016 01:25:06 (UTC+09) Magnitude 7.0 32.849oN 130.635oE Depth 10 kilometers 32.782oN 130.726oE Depth 10 kilometers Intensity 8.0 Apr-14 21:26 6.2 10.0 32.849 130.635 Apr-16 01:445.3 10.0 32.695 130.735 D Intensity 7.0 Apr-14 21:424.8 10.0 32.578 130.636 Apr-16 01:455.7 10.0 32.881 130.846 Intensity 8.5 Apr-14 22:075.4 10.0 32.788 130.835 Apr-16 02:044.6 11.7 32.757 130.742 Apr-14 22:224.8 10.0 32.683 130.646 Apr-16 02:494.5 12.2 33.203 131.321 M Apr-14 22:384.8 10.0 32.685 130.711 Apr-16 03:035.4 4.9 32.926 131.043 L Apr-14 22:434.5 10.0 32.704 130.696 Apr-16 03:164.6 18.6 33.086 130.836 J K B Apr-14 23:284.5 10.0 32.785 130.745 Apr-16 03:204.5 19.4 33.101 130.997 I Apr-14 23:294.6 10.0 32.752 130.726 Apr-16 03:264.5 10.0 32.870 130.918 A Aisin Kyushu Co. -

Detailed Fault Structure of the 2000 Western Tottori, Japan, Earthquake Sequence by Eiichi Fukuyama, William L

Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 93, No. 4, pp. 1468–1478, August 2003 Detailed Fault Structure of the 2000 Western Tottori, Japan, Earthquake Sequence by Eiichi Fukuyama, William L. Ellsworth, Felix Waldhauser, and Atsuki Kubo Abstract We investigate the faulting process of the aftershock region of the 2000 western Tottori earthquake (Mw 6.6) by combining aftershock hypocenters and mo- ment tensor solutions. Aftershock locations were precisely determined by the double difference method using P- and S-phase arrival data of the Japan Meteorological Agency unified catalog. By combining the relocated hypocenters and moment tensor solutions of aftershocks by broadband waveform inversion of FREESIA (F-net), we successfully resolved very detailed fault structures activated by the mainshock. The estimated fault model resolves 15 individual fault segments that are consistent with both aftershock distribution and focal mechanism solutions. Rupture in the main- shock was principally confined to the three fault elements in the southern half of the zone, which is also where the earliest aftershocks concentrate. With time, the northern part of the zone becomes activated, which is also reflected in the postseismic defor- mation field. From the stress tensor analysis of aftershock focal mechanisms, we found a rather uniform stress field in the aftershock region, although fault strikes were scattered. The maximum stress direction is N107ЊE, which is consistent with the tectonic stress field in this region. In the northern part of the fault, where no slip occurred during the mainshock but postseismic slip was observed, the maximum stress direction of N130ЊE was possible as an alternative solution of stress tensor inversion. -

(Appendix) Outline of Proposals for the Model Areas Selected in the Project

(Appendix) Outline of proposals for the model areas selected in the project to formulate community revitalization plans to achieve "low-carbon, sound material cycle and natural symbiosis" Model community Future vision/target Main measures to be taken over the next five years Shiriuchi Town, Shiriuchi: a sustainable town of Community revitalization by promoting the use of wood biomass heat, and Hokkaido self-reliance and independence utilizing “low-carbon, sound material-cycle and natural-symbiosis eco tours” utilizing the natural environment and manufacturing industry in the area; industrial vitalization by utilizing local products (Chinese chive) produced in a low-carbon and sound material-cycle local community. Shimokawa Town, Model of a “futuristic city with Establishment of a scheme for purchasing energy-saving home appliances Hokkaido forests” (establishment of a total without primary costs; training of town advisors for introducing home forestry industry and an energy renewable energy; examination of cost-effectiveness towards the supply of self-sufficiency system; a local biomass district heat to detached houses; verification of the establishment of community enabling all people from proposed energy-saving renovation models children to elderly to continue to live good lives) Tsubetsu Town, Tsubetsu: an environmental town Development of central heating facilities using wood biomass in public Hokkaido created with abundant nature housing; heat energy supply to certified children centers, agricultural greenhouses and special nursing