Entertainment Industries and the Trailer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9780367508234 Text.Pdf

Development of the Global Film Industry The global film industry has witnessed significant transformations in the past few years. Regions outside the USA have begun to prosper while non-traditional produc- tion companies such as Netflix have assumed a larger market share and online movies adapted from literature have continued to gain in popularity. How have these trends shaped the global film industry? This book answers this question by analyzing an increasingly globalized business through a global lens. Development of the Global Film Industry examines the recent history and current state of the business in all parts of the world. While many existing studies focus on the internal workings of the industry, such as production, distribution and screening, this study takes a “big picture” view, encompassing the transnational integration of the cultural and entertainment industry as a whole, and pays more attention to the coordinated develop- ment of the film industry in the light of influence from literature, television, animation, games and other sectors. This volume is a critical reference for students, scholars and the public to help them understand the major trends facing the global film industry in today’s world. Qiao Li is Associate Professor at Taylor’s University, Selangor, Malaysia, and Visiting Professor at the Université Paris 1 Panthéon- Sorbonne. He has a PhD in Film Studies from the University of Gloucestershire, UK, with expertise in Chinese- language cinema. He is a PhD supervisor, a film festival jury member, and an enthusiast of digital filmmaking with award- winning short films. He is the editor ofMigration and Memory: Arts and Cinemas of the Chinese Diaspora (Maison des Sciences et de l’Homme du Pacifique, 2019). -

Etiek En Toeskouerskap Deur Die Lens Van Michael Haneke Se Amour

LitNet Akademies Jaargang 15, Nommer 2, 2018, ISSN 1995-5928 Verantwoordelike rolprentvervaardiging: etiek en toeskouerskap deur die lens van Michael Haneke se Amour Dian Weys Dian Weys, onafhanklike navorser Opsomming Aangesien ons moderne samelewing deur die media oorweldig word, stel Michael Haneke voor dat filmmakers ‘n verantwoordelikheid het om gehore aan te moedig om aan ‘n film se betekenisskeppingproses deel te neem, veral wanneer dit kom by die uitbeelding van geweld. Wat behels hierdie verantwoordelikheid? Stanley Cavell verduidelik dat, omdat toeskouers tydens die filmkykproses onsigbaar is, film ‘n beroep op ons moderne begeerte doen, nie vir mag oor die wêreld nie, maar eerder die wens om nie mag nodig te hê nie en om nie die laste van ‘n ander te dra nie. Dit is ‘n probleem, glo ek, veral wanneer iemand anders se werklike swaarkry en lyding as bronmateriaal gebruik word, omdat filmmakers dié werklike ervaring wederregtelik in besit neem vir vermaaklikheidsonthalwe. Indien die filmkykproses ons kwytskeld daarvan om die laste van die wêreld te dra en dus verligting bied van die opneem van verantwoordelikheid, argumenteer ek dat ons nie mag wens om nie die laste van iemand anders te dra nie. Ons is, soos Emmanuel Levinas argumenteer, verantwoordelik vir mekaar. Hoe poog Haneke om, tegnies gewys, sy gehore bewus te maak van hierdie verantwoordelikheid? Judith Butler sê dat ‘n begrip van verantwoordelikheid net bereik kan word wanneer ‘n ek-heid die perke van selfkennis erken. Daarom, indien ons, soos Butler sê, net bewus kan raak van die ondeursigtigheid eie aan ons menswees wanneer ons gekonfronteer word met die ondeursigtigheid van ‘n ander, argumenteer ek dat Haneke, deur sy fragmentariese aanslag ten opsigte van die beeld, redigering en klank, sy gehoor in verwantskap plaas met ‘n film wat hul met die perke van hul selfkennis konfronteer. -

Thinking About

THINKING ABOUT Watching, Questioning, Enjoging FOURTH EDITION PETER LEHMAN and WILLIAM LUHR Wiley Biackweii CONTENTS List of Figures ix How to Use This Book xvi Acknowledgments xix About the Companion Blog xxi 1 Introduction 1 Fatal Attraction and Scarface 2 Narrative Structure 27 Jurassic Park and Rashomon 3 Formal Analysis 61 Rules of the Game and The Sixth Sense 4 Authorship 87 The Searchers and Jungle Fever 5 Genres 111 Sin City and Gunfight at the OK Corral 6 Series, Sequels, and Remakes 141 Goldfinger and King Kong (1933 and 2005) 7 Actors and Stars 171 Morocco and Dirty Harry 8 Audiences and Reception 197 A Woman ofParis and The Crying Game 9 Film and the Other Arts 222 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1933) and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011) 10 Film and its Relation to Radio and Television 257 Richard Diamond, Private Detective; Peter Gunn; Victor/Victoria; 24\ and Homeland 11 Realism and Theories of Film 296 Tlje Battleship Potemkin and Umberto D 12 Gender and Sexuality 317 The Silence of the Lambs and American Gigolo 13 Race 341 Out of the Past, LA Confidential, and Boyz N the Hood 14 Class 371 Pretty Woman and The People Under the Stairs 15 Citizen Kane: An Analysis 396 Citizen Kane 16 Current Trends: Globalization and China, 3D, IMAX, Internet TV 419 Glossary 441 Index 446 LIST Of FIGURES Chapter 1 1.1 Zero Dark Thirty, © 2012 Zero Dark Thirty LLC 1 1.2 American Sniper, © 2014 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc, Village Roadshow Films North America Inc. and Ratpac-Dune Entertainment LLC 1 1.3 Spotlight, © 2015 SPOTLIGHT FILM, LLC 2 1.4 Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit, © 2013 Paramount Pictures Corporation 2 1.5 Dragon: The Brace Lee Story, © 1992, Universal 3 1.6 Breakfast at Tiffany's, © 1961, Paramount 3 1.7 Psycho, © 1960, Universal 3 1.8 The Hills Have Eyes (2006), © 2006 BRC Rights Management, LTD 4 1.9 The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003), © 2003 Chainsaw Productions, LLC 4 1.10 Son of the Pink Panther (1993), © United Artists Productions, Inc. -

Las Alas De Ícaro: El Trailer Cinematogáfico, Un Tejido Artístico De Sueños

Las Alas de Ícaro: El un tejido artístico de sueños. Las Alas de Ícaro: El trailer cinematogáfico, un tejido artístico de sueños. Tesis doctoral presentada por María Lois Campos, bajo la dirección del doctor D. José Chavete Rodríguez. Facultad de Bellas Artes, Departamento de Pintura de la Universidad de Vigo. Pontevedra 2014 / 2015 AGRADECIMIENTOS Quiero expresar mis más sincero agradecimiento a todas aquellas personas que me han apoyado y motivado a lo largo de mis estudios. Voy a expresar de un modo especial mis agradecimientos: • En particular agradezco al Profesor José Chavete Rodríguez la confianza que ha depositado en mí para la realización de esta investigación; por su apoyo, trato esquisito, motivación constante y sabios consejos a lo largo de dicho proceso. • En especial agradezco a Joaquina Ramilo Rouco (Documentalista- Information Manager) su paciencia a la hora de intentar resolver mis dudas. • También expreso mi reconocimiento al servicio de Préstamo Interbibliotecario (Tita y Asunción) y al servicio de Referencia de la Universidad de Vigo, así como a Héctor, Morquecho, Fernando, Begoña (Biblioteca de Ciencias Sociales de Pontevedra) y al personal de la Biblioteca de Torrecedeira en Vigo. • Quisiera hacer extensiva mi gratitud al profesor Suso Novás Andrade y a Ana Celia (Biblioteca de Bellas Artes) por el tiempo invertido a la hora de solventar mis dudas a lo largo del proceso de investigación. • Debo asimismo, mostrar un agradecimiento ante el hecho de haber sido alumna de Juan Luís Moraza Pérez, Consuelo Matesanz Pérez, Manuel Sendón Trillo, Fernando Estarque Casás, Alberto Ruíz de Samaniego y Rosa Elvira Caamaño Fernández, entre otros profesores, por haber aportado sus conocimientos, así como mostrarme otros universos en torno al arte. -

'The Coolest Way to Watch Movie Trailers in the World': Trailers in the Digital Age Keith M. Johnston

1 This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14, 2 (2008): 145- 60, (c) Sage Publications Available online at: http://con.sagepub.com/content/14/2/145.full.pdf+html DOI: 10.1177/1354856507087946 ‘The Coolest Way to Watch Movie Trailers in the World’: Trailers in the Digital Age Keith M. Johnston Abstract At a time of uncertainty over film and television texts being transferred online and onto portable media players, this article examines one of the few visual texts that exists comfortably on multiple screen technologies: the trailer. Adopted as an early cross-media text, the trailer now sits across cinema, television, home video, the Internet, games consoles, mobile phones and iPods. Exploring the aesthetic and structural changes the trailer has undergone in its journey from the cinema to the iPod screen, the article focuses on the new mobility of these trailers, the shrinking screen size, and how audience participation with these texts has influenced both trailer production and distribution techniques. Exploring these texts, and their technological display, reveals how modern distribution techniques have created a shifting and interactive relationship between film studio and audience. Key words: trailer, technology, Internet, iPod, videophone, aesthetics, film promotion 2 In the current atmosphere of uncertainty over how film and television programmes are made available both online and to mobile media players, this article will focus on a visual text that regularly moves between the multiple screens of cinema, television, computer and mobile phone: the film trailer. A unique text that has often been overlooked in studies of film and media, trailer analysis reveals new approaches to traditional concerns such as stardom, genre and narrative, and engages in more recent debates on interactivity and textual mobility. -

Learning Trailer Moments in Full-Length Movies with Co-Contrastive Attention

Learning Trailer Moments in Full-Length Movies with Co-Contrastive Attention Lezi Wang1?, Dong Liu2, Rohit Puri3??, and Dimitris N. Metaxas1 1Rutgers University, 2Netflix, 3Twitch flw462,[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. A movie's key moments stand out of the screenplay to grab an audience's attention and make movie browsing efficient. But a lack of annotations makes the existing approaches not applicable to movie key moment detection. To get rid of human annotations, we leverage the officially-released trailers as the weak supervision to learn a model that can detect the key moments from full-length movies. We introduce a novel ranking network that utilizes the Co-Attention between movies and trailers as guidance to generate the training pairs, where the moments highly corrected with trailers are expected to be scored higher than the uncorrelated moments. Additionally, we propose a Contrastive Attention module to enhance the feature representations such that the compara- tive contrast between features of the key and non-key moments are max- imized. We construct the first movie-trailer dataset, and the proposed Co-Attention assisted ranking network shows superior performance even over the supervised1 approach. The effectiveness of our Contrastive At- tention module is also demonstrated by the performance improvement over the state-of-the-art on the public benchmarks. Keywords: Trailer Moment Detection, Video Highlight Detection, Co- Contrastive Attention, Weak Supervision, Video Feature Augmentation. 1 Introduction \Just give me five great moments and I can sell that movie." { Irving Thalberg (Hollywood's first great movie producer). Movie is made of moments [34], while not all of the moments are equally important. -

Starlog Magazine

TWILIGHT FRINGE Meet DVD Extras! INDIANA JONES Agent vampire PLANET OF THE APES Anna 1 hero Robert HELLBOY* QUARK* X-FILES Torv Pattinson STARLOG Movie Magic presents debriefs Animated Adventures FUTURAMA* BOLT MADAGASCAR 2 TV's Newest Fantasy LEGEND OF THE SEEKER James Bond returns for Qbloody vengeance UANTUM " OF S LACE Mm $7.99 U.S. & CANADA 1 2 "09128"43033" www.starlog.com NUMBER 371 • DECEMBER 2008 • THE SCIENCE FICTION UNIVERSE STARLOC 17 QUANTUM OF SOLACE James Bond returns with vengeance in mind 22 LEGEND OF THE SEEKER BEGINS Ken Biller brings Trek expertise to this new fantasy odyssey 28 VAMPIRE IN TWILIGHT Fans are learning to love Robert Pattinson 32 WOMAN ON THE FRINGE Anna Torv is a tough but lovely FBI agent 51 VISIONS OF HELLBOY Wayne Barlowe unveils his artistic impressions 56 END OF THE X-FILES Frank Spotnitz ponders its secrets big & small 60 QUARK ON DVD Cast & crew salute the fabled spoof's legacy of laughter 66 INDIANA JONES & ME Dimitri Diatchenko recalls their escapades 70 INTO THE KNIGHT Justin Bruening takes the wheel of KITT 74 TERMINATORS OF TOMORROW The Sarah Connor Chronicles hosts them today & yesterday 78 SF-TV SECRETS REVEALED! Planet of the Apes offered small-screen simians ANIMATION SCENE 36 HE'S AN AMERICAN DOG! Bolt's CC adventures take him cross-country 41 FORCE 10 FROM MADAGASCAR The zoosters ship out for sequel action 46 IN THE FUTURAMA DAZE David x. Cohen's just happy to be making more & more toons Photo: Karen Ballard/Copyright 2008 Danjaq, LLC, United Artists Corporation & Columbia Pictures Industries?!" All Rights Reserved. -

Uk Producers in Cannes 2009

UK PRODUCERS IN CANNES 2009 Produced by Export Development www.ukfilmcouncil.org/exportteam The UK Film Council The UK Film Council is the Government-backed lead agency for film in the UK ensuring the economic, cultural and educational aspects of films are effectively represented at home and abroad. Our goal is to help make the UK a global hub for film in the digital age, with the world’s most imaginative, diverse and vibrant film culture, underpinned by a flourishing, competitive film industry. We invest Government grant-in-aid and Lottery money in developing new filmmakers, in funding new British films and in getting a wider choice of films to audiences throughout the UK. We also invest in skills training, promoting Britain as an international filmmaking location and in raising the profile of British films abroad. The UK Film Council Export Development team Our Export Development team supports the export of UK films and talent and services internationally in a number of different ways: Promoting a clear export strategy Consulting and working with industry and government Undertaking export research Supporting export development schemes and projects Providing export information The team is located within the UK Film Council’s Production Finance Division and is part of the International Group. Over the forthcoming year, Export Development will be delivering umbrella stands at the Toronto International Film Festival and Hong Kong Filmart; and supporting the UK stands at the Pusan Asian Film Market; American Film Market and the European Film Market, Berlin;. The team will also be leading Research & Development delegations to Japan and China. -

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960S Promotional Featurettes

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960s Promotional Featurettes by DANIEL STEINHART Abstract: Before making-of documentaries became a regular part of home-video special features, 1960s promotional featurettes brought the public a behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood’s production process. Based on historical evidence, this article explores the changes in Hollywood promotions when studios broadcasted these featurettes on television to market theatrical films and contracted out promotional campaigns to boutique advertising agencies. The making-of form matured in the 1960s as featurettes helped solidify some enduring conventions about the portrayal of filmmaking. Ultimately, featurettes serve as important paratexts for understanding how Hollywood’s global production work was promoted during a time of industry transition. aking-of documentaries have long made Hollywood’s flm production pro- cess visible to the public. Before becoming a staple of DVD and Blu-ray spe- M cial features, early forms of making-ofs gave audiences a view of the inner workings of Hollywood flmmaking and movie companies. Shortly after its formation, 20th Century-Fox produced in 1936 a flmed studio tour that exhibited the company’s diferent departments on the studio lot, a key feature of Hollywood’s detailed division of labor. Even as studio-tour short subjects became less common because of the restructuring of studio operations after the 1948 antitrust Paramount Case, long-form trailers still conveyed behind-the-scenes information. In a trailer for The Ten Commandments (1956), director Cecil B. DeMille speaks from a library set and discusses the importance of foreign location shooting, recounting how he shot the flm in the actual Egyptian locales where Moses once walked (see Figure 1). -

In the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas Houston Division

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION TINA M. RANDOLPH, § § Plaintiff, § § v. § CIVIL ACTION NO. H-08-1836 § DIMENSION FILMS et al.,§ § Defendants. § MEMORANDUM AND ORDER In this action brought under the Copyright Act of 1976, as amended, 17 U.S.C. § 101 et seq., plaintiff Tina M. Randolph, the author of a book published by her “dba,” Rhapsody Publishing, alleges that the defendants infringed on her copyright. The book is Mystic Deja: Maze of Existence, the first of an anticipated twelve-volume science-fiction series. Randolph published it in December 2002. In this suit, she alleges that the defendants’ motion picture, The Adventures of Shark Boy and Lava Girl in 3-D, infringed on her copyrighted book. Randolph also asserts claims for unfair competition under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a), and for violations of the Texas Deceptive Trade Practices Act (DTPA), TEX. BUS. & COM. CODE §§ 17.45(4), 17.50. The defendants, Dimension Films, Miramax Film Corp., SONY Pictures Entertainment, Inc., Buena Vista Home Entertainment, Inc., Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc., The Walt Disney Co., Troublemaker Studios, Robert Rodriguez, Racer Max Rodriguez, and Elizabeth Avellan, have moved to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Randolph attached to her complaint cover artwork from the book and from the allegedly infringing movie, as well as a press release for the series and part of the book. The defendants attached to their motion to dismiss a copy of Randolph’s book and of their movie, which this court has read and watched. -

Cigarette Smoking and Perception of a Movie Character in a Film Trailer

ARTICLE Cigarette Smoking and Perception of a Movie Character in a Film Trailer Reiner Hanewinkel, PhD Objective: To study the effects of smoking in a film named “attractiveness.” The Cronbach ␣ for the attrac- trailer. tiveness rating was 0.85. Design: Experimental study. Results: Multilevel mixed-effects linear regression was used to test the effect of smoking in a film trailer. Smoking in the Setting: Ten secondary schools in Northern Germany. film trailer did not reach significance in the linear regres- sion model (z=0.73; P=.47). Smoking status of the recipi- Participants: A sample of 1051 adolescents with a mean ent (z=3.81; PϽ.001) and the interaction between smok- (SD) age of 14.2 (1.8) years. ing in the film trailer and smoking status of the recipient (z=2.21; P=.03) both reached statistical significance. Ever Main Exposures: Participants were randomized to smokers and never smokers did not differ in their percep- view a 42-second film trailer in which the attractive tion of the female character in the nonsmoking film trailer. female character either smoked for about 3 seconds or In the smoking film trailer, ever smokers judged the char- did not smoke. acter significantly more attractive than never smokers. Main Outcome Measures: Perception of the charac- Conclusion: Even incidental smoking in a very short film ter was measured via an 8-item semantic differential scale. trailer might strengthen the attractiveness of smokers in Each item consisted of a polar-opposite pair (eg, “sexy/ youth who have already tried their first cigarettes. unsexy”) divided on a 7-point scale. -

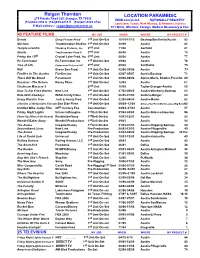

Raigen Thornton LOCATION PARAMEDIC

Raigen Thornton LOCATION PARAMEDIC 275 Private Road 925, Granger, TX 76530 IMDB.com Listed NATIONALLY REGISTRY (512)924-7800 C (512)859-2810 H (512)287-4345 eFax Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, & Arizona Licenses E-Mail address: [email protected] 911 MICU, Offshore, Foreign, Medical Missionary & Film 45 FEATURE FILMS MY JOB WHEN WHERE MY PROJECT # Bernie Deep Freeze Prod 1st Unit On-Set 10/10-11/10 Bastrop/Smithville/Austin 85 Machete Troublemaker Studios 1st Unit On-Set 08/09 Austin 82 Temple Grandin Thinking Pictures, Inc 2nd Unit 11/08 Garfield 81 Shorts Troublemaker Prod 5 2nd Unit 06/08 Austin 78 Friday the 13th Crystal Lake Prod, Inc 2nd Unit 06/08 Austin 77 Ex-Terminator Ex-Terminator Inc 1st Unit On-Set 05/08 Austin 76 Tree of Life Cottonwood Pictures LLC 2nd Unit 05/08 Smithville 75 Will Green Sea Prod. 1st Unit On-Set 02/08-03/08 Austin 73 Fireflies In The Garden Fireflies Inc 1st Unit On-Set 03/07-05/07 Austin/Bastrop 71 There Will Be Blood Paramount 1st Unit On-Set 03/06-08/06 Alpine,Marfa, Shafter,Presidio 69 Revolver –The Return Rosey Films 1st Unit On-Set 12/05 Austin 67 Chainsaw Masacre-3 2nd Unit 10/05 Taylor-Granger-Austin 66 How To Eat Fried Worms New Line 1st Unit On-Set 07/05-09/05 Austin-Wimberly-Bastrop 65 Ride With Cowboys IMAX-Trinity Films 1st Unit On-Set 06/05-07/05 Guthrie-Borger 63 Every Word Is True Jack & Henry Prod. 1st Unit On-Set 02/05-04/05 Austin-Marlin 62 3 Burials of Melquiades Estrada-Sea Side Films 1st Unit On-Set 09/04–12/04 Odessa-VanHorn-Marfa-Lajitas-Big Bend60 Untitled Mike Judge Film 20th