Bruckner Latin Motets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5, 2020 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

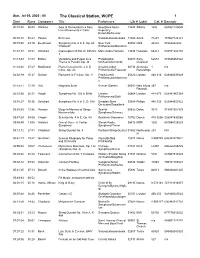

Sun, Jul 05, 2020 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 05:50 Watkins Soul of Remembrance from New Black Music 13225 Albany 1200 034061120025 Five Movements in Color Repertory Ensemble/Dunner 00:08:3505:43 Paulus Berceuse Yolanda Kondonassis 11483 Azica 71281 787867128121 00:15:4844:19 Beethoven Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 New York 08852 CBS 42222 07464422222 "Pastoral" Philharmonic/Bernstein 01:01:37 10:51 Schubert Impromptu in B flat, D. 935 No. Marc-Andre Hamelin 13496 Hyperion 68213 034571282138 3 01:13:4317:49 Britten Variations and Fugue on a Philadelphia 04033 Sony 62638 074646263822 Theme of Purcell, Op. 34 Orchestra/Ormandy Classical 01:33:02 27:47 MacDowell Piano Concerto No. 2 in D Amato/London 00734 Archduke 1 n/a minor, Op. 23 Philharmonic/Freeman Recordings 02:02:1910:37 Dvorak Romance in F minor, Op. 11 Frank/Czech 05323 London 460 316 028946031629 Philharmonic/Mackerra s 02:14:1117:25 Dett Magnolia Suite Denver Oldham 05092 New World 367 n/a Records 02:33:0626:51 Haydn Symphony No. 102 in B flat London 00664 London 414 673 028941467324 Philharmonic/Solti 03:01:2730:36 Schubert Symphony No. 6 in C, D. 589 Dresden State 03988 Philips 446 539 028944653922 Orchestra/Sawallisch 03:33:3312:36 Hanson Elegy in Memory of Serge Seattle 00825 Delos 3073 013491307329 Koussevitsky Symphony/Schwarz 03:47:2409:55 Chopin Scherzo No. 4 in E, Op. 54 Benjamin Grosvenor 10752 Decca 478 3206 028947832065 03:58:49 13:08 Harbach One of Ours - A Cather Slovak Radio 08416 MSR 1252 681585125229 Symphony Symphony/Trevor 04:13:1227:41 Chadwick String Quartet No. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 27,1907-1908, Trip

CARNEGIE HALL - - NEW YORK Twenty-second Season in New York DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor fnigrammra of % FIRST CONCERT THURSDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 7 AT 8.15 PRECISELY AND THK FIRST MATINEE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, NOVEMBER 9 AT 2.30 PRECISELY WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER : Piano. Used and indorsed by Reisenauer, Neitzel, Burmeister, Gabrilowitsch, Nordica, Campanari, Bispham, and many other noted artists, will be used by TERESA CARRENO during her tour of the United States this season. The Everett piano has been played recently under the baton of the following famous conductors Theodore Thomas Franz Kneisel Dr. Karl Muck Fritz Scheel Walter Damrosch Frank Damrosch Frederick Stock F. Van Der Stucken Wassily Safonoff Emil Oberhoffer Wilhelm Gericke Emil Paur Felix Weingartner REPRESENTED BY THE JOHN CHURCH COMPANY . 37 West 32d Street, New York Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SEVENTH SEASON, 1907-1908 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor First Violins. Wendling, Carl, Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Krafft, W. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J. Czerwonky, R. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. < Second Violins. • Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Rennert, B. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H Kuntz, A. Swornsbourne, W. Goldstein, S. Kurth, R. Goldstein, H. Violas. Ferir, E. Heindl, H. Zahn, F. Kolster, A. Krauss, H. Scheurer, K. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M. Sauer, G. Gietzen, A. t Violoncellos. Warnke, H. Nagel, R. Barth, C. Loefner, E. Heberlein, H. Keller, J. Kautzenbach, A. Nast, L. -

THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC of BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented To

Z 2 THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC OF BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Theodore J. Albrecht, B. M. E. Denton, Texas May, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. .................. iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION............... ............. II. EGMONT.................... ......... 0 0 05 Historical Background Egmont: Synopsis Egmont: the Music III. KONIG STEPHAN, DIE RUINEN VON ATHEN, DIE WEIHE DES HAUSES................. .......... 39 Historical Background K*niq Stephan: Synopsis K'nig Stephan: the Music Die Ruinen von Athen: Synopsis Die Ruinen von Athen: the Music Die Weihe des Hauses: the Play and the Music IV. THE LATER PLAYS......................-.-...121 Tarpe.ja: Historical Background Tarpeja: the Music Die gute Nachricht: Historical Background Die gute Nachricht: the Music Leonore Prohaska: Historical Background Leonore Prohaska: the Music Die Ehrenpforten: Historical Background Die Ehrenpforten: the Music Wilhelm Tell: Historical Background Wilhelm Tell: the Music V. CONCLUSION,...................... .......... 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY.....................................-..145 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Egmont, Overture, bars 28-32 . , . 17 2. Egmont, Overture, bars 82-85 . , . 17 3. Overture, bars 295-298 , . , . 18 4. Number 1, bars 1-6 . 19 5. Elgmpnt, Number 1, bars 16-18 . 19 Eqm 20 6. EEqgmont, gmont, Number 1, bars 30-37 . Egmont, 7. Number 1, bars 87-91 . 20 Egmont,Eqm 8. Number 2, bars 1-4 . 21 Egmon t, 9. Number 2, bars 9-12. 22 Egmont,, 10. Number 2, bars 27-29 . 22 23 11. Eqmont, Number 2, bar 32 . Egmont, 12. Number 2, bars 71-75 . 23 Egmont,, 13. -

Grosser Saal Klangwolke Brucknerhaus Präsentiert Von Der Linz Ag Linz

ZWISCHEN CREDO Vollendeter Genuss TRADITION BEKENNTNIS braucht ein & GLAUBE perfektes MODERNE Zusammenspiel RELIGION Als führendes Energie- und Infrastrukturunternehmen im oberösterreichischen Zentralraum sind wir ein starker Partner für Wirtschaft, Kunst und Kultur und die Menschen in der Region. Die LINZ AG wünscht allen Besucherinnen und Besuchern beste Unterhaltung. bezahlte Anzeige LINZ AG_Brucknerfest 190x245.indd 1 02.05.18 10:32 6 Vorworte 12 Saison 2018/19 16 Abos 2018/19 22 Das Große Abonnement 32 Sonntagsmatineen 44 Internationale Orchester 50 Bruckner Orchester Linz 56 Kost-Proben 60 Das besondere Konzert 66 Oratorien 128 Hier & Jetzt 72 Chorkonzerte 134 Moderierte Foyer-Konzerte INHALTS- 78 Liederabende 138 Musikalischer Adventkalender 84 Streichquartette 146 BrucknerBeats 90 Kammermusik 150 Russische Dienstage 96 Stars von morgen 154 Musik der Völker 102 Klavierrecitals 160 Jazz VERZEICHNIS 108 Orgelkonzerte 168 Jazzbrunch 114 Orgelmusik zur Teatime 172 Gemischter Satz 118 WortKlang 176 Kinder.Jugend 124 Ars Antiqua Austria 196 Serenaden 204 Kooperationen 216 Kalendarium 236 Saalpläne 242 Karten & Service 4 5 Linz hat sich schon längst als interessanter heimischen, aber auch internationalen Künst- Der Veröffentlichung des neuen Saisonpro- Musik wird heutzutage bevorzugt über diverse und innovativer Kulturstandort auch auf in- lerinnen und Künstlern es ermöglichen, ihr gramms des Brucknerhauses Linz sehen Medien, vom Radio bis zum Internet, gehört. ternationaler Ebene Anerkennung verschafft. Potenzial abzurufen und sich zu entfalten. Für unzählige Kulturinteressierte jedes Jahr er- Dennoch hat die klassische Form des Konzerts Ein wichtiger Meilenstein auf diesem Weg war alle Kulturinteressierten jeglichen Alters bietet wartungsvoll entgegen. Heuer dürfte die nichts von ihrer Attraktivität eingebüßt. Denn bislang auf jeden Fall die Errichtung des Bruck- das ausgewogene und abwechslungsreiche Spannung besonders groß sein, weil es die das Live-Erlebnis bleibt einzigartig – dank der nerhauses Linz. -

Unit 7 Romantic Era Notes.Pdf

The Romantic Era 1820-1900 1 Historical Themes Science Nationalism Art 2 Science Increased role of science in defining how people saw life Charles Darwin-The Origin of the Species Freud 3 Nationalism Rise of European nationalism Napoleonic ideas created patriotic fervor Many revolutions and attempts at revolutions. Many areas of Europe (especially Italy and Central Europe) struggled to free themselves from foreign control 4 Art Art came to be appreciated for its aesthetic worth Program-music that serves an extra-musical purpose Absolute-music for the sake and beauty of the music itself 5 Musical Context Increased interest in nature and the supernatural The natural world was considered a source of mysterious powers. Romantic composers gravitated toward supernatural texts and stories 6 Listening #1 Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique (4th mvmt) Pg 323-325 CD 5/30 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QwCuFaq2L3U 7 The Rise of Program Music Music began to be used to tell stories, or to imply meaning beyond the purely musical. Composers found ways to make their musical ideas represent people, things, and dramatic situations as well as emotional states and even philosophical ideas. 8 Art Forms Close relationship Literature among all the art Shakespeare forms Poe Bronte Composers drew Drama inspiration from other Schiller fine arts Hugo Art Goya Constable Delacroix 9 Nationalism and Exoticism Composers used music as a tool for highlighting national identity. Instrumental composers (such as Bedrich Smetana) made reference to folk music and national images Operatic composers (such as Giuseppe Verdi) set stories with strong patriotic undercurrents. Composers took an interest in the music of various ethnic groups and incorporated it into their own music. -

Vida De Anton Bruckner

CICLO BRUCKNER ENERO 1996 Fundación Juan March CICLO BRUCKNER ENERO 1996 ÍNDICE Pág. Presentación 3 Cronología básica 5 Programa general 7 Introducción general, por Angel-Fernando Mayo 11 Notas al programa: Primer concierto 17 Segundo concierto 21 Textos de las obras cantadas 25 Tercer concierto 31 Participantes 35 Antón Bruckner es hoy uno de los sinfonistas más prestigiosos del siglo XIX. Ya son páginas de historia de la música su ferviente admiración por Wagnery las diatribas que Hanslicky los partidarios de Brahms mantuvieron entonces respecto a su arte sinfónico, y un capítulo importante de la historia de la difusión musical lo ocupa la lenta recepción de su obra hasta el triunfo incuestionable de los últimos años. Pero Bruckner es también autor de un buen número de obras corales, con o sin acompañamiento de órgano, y de muy pocas pero significativas obras de cámara. También escribió para órgano -aunque siempre añoraremos más y más ambiciosas obras en quien fue organista profesional-, algo para piano y muy pocas canciones. En este ciclo, que no puede acercarse al mundo sinfónico, hemos acogido la mayor parte de su obra camerística centrándola en su importante Quinteto para cuerda, y una buena antología de su obra coral, desde la temprana Misa para el Jueves Santo de 1844 hasta ejemplos de su estilo final en 1885, en la época de su explosión sinfónica. Más de cuarenta años de actividad musical que ayudará al buen aficionado a completar la imagen de uno de los músicos más importantes del posromanticismo. Para no dejar aislado el Cuarteto de cuerda de 1862, hemos programado uno de los de su colega y contrincante Brahms. -

¥T1 Id -'F- L~R~J Was That Performance of " Tannhauser" in 1863 Which, According ~.'Tkon"-"'1

rro te above literally the lyric initial theme of the symphony arming for III. Scherzo: Sehr schnell (very fast), A minor, 3/ 4 thus with battle" : Trio: Etwas langsamer (a little slower), F major, 3/ 4 , two per IV_ Finale : B ~wegt, do ch nicht schnell (with motion but not fast), nat is here eJC..tof. E major, alla breve any emen "'t;" DOC" ,~::;; OG~LL ~ ~ ,----. t only the IVa; $; 4'3 3.7 IrS· k11 J pelr Sh'/Jd I p VIOl.1NS x: .. The symphony is scored for two each of flutes, oboes, clarinets, Late advan and bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, two Ir'* fJrtD Iqr\J t"VI!t ~6IhJq;;j &J J I # tenor-tubas and two bass-tubas ("Wagner-Tuben"), contrabass not of the ) " \.....:...-. ,. > J Poco '" POc.O C.R.E5C.. tuba, timpani, and strings. climax. A only direct The launching of this melodic arrow by the bows of the violins lsic moves is sharpened by Bruckner's indication to play "with the point." Overture in G minor cribe or to The second subj ect is the simplest of simpl e ideas, transformed Few, if any, of the great composers were so late in maturing ;kn er here by the co mposer's mastery of orchestration into a chorale of utter as Bruckn er. The overture in G minor remains, if compared to ~me ntation genius. It may be nothing more than "an exercise in modulating any of the nine symphonies, a transitional if not a student produc i, pi::.::icato. cadences," technicall y speaking, but one that no student could tion. -

Bläserphilharmonie Mozarteum Salzburg

BLÄSERPHILHARMONIE MOZARTEUM SALZBURG DANY BONVIN GALACTIC BRASS GIOVANNI GABRIELI ERNST LUDWIG LEITNER RICHARD STRAUSS ANTON BRUCKNER WERNER PIRCHNER CD 1 WILLIAM BYRD (1543–1623) (17) Station XIII: Jesus wird vom Kreuz GALAKTISCHE MUSIK gewesen ist. In demselben ausgehenden (1) The Earl of Oxford`s March (3'35) genommen (2‘02) 16. Jahrhundert lebte und wirkte im Italien (18) Station XIV: Jesus wird ins „Galactic Brass“ – der Titel dieses Pro der Renaissance Maestro Giovanni Gabrieli GIOVANNI GABRIELI (1557–1612) Grab gelegt (1‘16) gramms könnte dazu verleiten, an „Star im Markusdom zu Venedig. Auf den einander (2) Canzon Septimi Toni a 8 (3‘19) Orgel: Bettina Leitner Wars“, „The Planets“ und ähnliche Musik gegenüber liegenden Emporen des Doms (3) Sonata Nr. XIII aus der Sterne zu denken. Er meint jedoch experimentierte Gabrieli mit Ensembles, „Canzone e Sonate” (2‘58) JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACh (1685–1750) Kom ponisten und Musik, die gleichsam ins die abwechselnd mit und gegeneinander (19) Passacaglia für Orgel cMoll, BWV 582 ERNST LUDWIG LEITNER (*1943) Universum der Zeitlosigkeit aufgestiegen musizierten. Damit war die Mehrchörigkeit in der Fassung für acht Posaunen sind, Stücke, die zum kulturellen Erbe des gefunden, die Orchestermusik des Barock Via Crucis – Übermalungen nach den XIV von Donald Hunsberger (6‘15) Stationen des Kreuzweges von Franz Liszt Planeten Erde gehören. eingeleitet und ganz nebenbei so etwas für Orgel, Pauken und zwölf Blechbläser, RICHARD STRAUSS (1864–1949) wie natürliches Stereo. Die Besetzung mit Uraufführung (20) Feierlicher Einzug der Ritter des William Byrd, der berühmteste Komponist verschiedenen Blasinstrumenten war flexibel JohanniterOrdens, AV 103 (6‘40) Englands in der Zeit William Shakespeares, und wurde den jeweiligen Räumen ange (4) Hymnus „Vexilla regis“ (1‘12) hat einen Marsch für jenen Earl of Oxford passt. -

Yevhen Stankovych: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

YEVHEN STANKOVYCH: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1967-68: Overture 1968: Concertino for Flute, Violin and Orchestra 1969-73: “Mountain Symphony” 1970: Cello Concerto Cantata “The Word of Lenin” for soloists, chorus and orchestra 1971: Sinfonietta: 17 minutes 1972: Phantasy on Ukrainian, Latvian and Armenian Folk themes for orchestra 1973: Symphony No.1 “Sinfonia Larga” for fifteen strings: 18 minutes * + (Marco Polo cd) 1975: Symphony No. 2 “Eroica”: 28 minutes * + (Marco Polo cd) 1975-76: Symphony No.3 “I strengthen myself” for baritone, chorus and orchestra: 29 minutes * 1977: Symphony No.4 “Sinfonia Lyrica” for sixteen strings and cello: 26 minutes * + (Marco Polo cd) 1979: Elegy in memory of S. Lindkevych sor string orchestra: 4 minutes 1980: Symphony No.5 “Pastoral” for violin and orchestra: 36 minutes * + (Consonance cd) Chamber Concerto No.2 “Meditation” for two flutes, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, piano, percussion and strings: 15 minutes + (Consonance and TNC cds) 1981: Ballet-Legend “Olga” 1983: Chamber Symphony No.3 for flute and twelve strings: 18 minutes * + (Nimbus and TNC cds) Ballet “Spark” 1985: Ballet “Prometheus” 1986: Ballet “A Night in May” 1987: Symphony No.6 “Dictum” for small orchestra: 27 minutes * Chamber Symphony No.4 “In Memory of a Poet” for baritone, piano and fifteen strings: 27 minutes + (TNC cds) 1990: Ballet “Rasputin” (and Ballet Suite: 20 minutes) Ballet “The Night Before Christmas” 1991: Requiem-Kaddish “Babi Yar” for narrator, tenor, bass, chorus and orchestra “Black Elegy” for soloists, chorus -

Bruckner Und Seine Schüler*Innen

MUTIGE IMPULSE BRUCKNER UND SEINE SCHÜLER*INNEN Bürgermeister Klaus Luger Aufsichtsratsvorsitzender Mag. Dietmar Kerschbaum Künstlerischer Vorstandsdirektor LIVA Intendant Brucknerhaus Linz Dr. Rainer Stadler Kaufmännischer Vorstandsdirektor LIVA VORWORT Anton Bruckners Die Neupositionierung des Inter- ein roter Faden durch das Pro- musikalisches Wissen nationalen Brucknerfestes Linz gramm, das ferner der Linzerin liegt mir sehr am Herzen. Ich Mathilde Kralik von Meyrswal- Der Weitergabe seines Wissens förderprogramm mit dem Titel wollte es wieder stärker auf An- den einen Schwerpunkt widmet, im musikalischen Bereich wid- an_TON_Linz ins Leben gerufen ton Bruckner fokussieren, ohne die ebenfalls bei Bruckner stu- mete Anton Bruckner ein beson- hat. Es zielt darauf ab, künstleri- bei der Vielfalt der Programme diert hat. Ich freue mich, dass deres Augenmerk. Den Schü- sche Auseinandersetzungen mit Abstriche machen zu müssen. In- viele renommierte Künstler*in- ler*innen, denen er seine Fähig- Anton Bruckner zu motivieren dem wir jede Ausgabe unter ein nen und Ensembles unserer keiten als Komponist vermittelt und seine Bedeutung in eine Motto stellen, von dem aus sich Einladung gefolgt sind. Neben hat, ist das heurige Internationa- Begeisterung umzuwandeln. bestimmte Aspekte in Bruckners Francesca Dego, Paul Lewis, le Brucknerfest Linz gewidmet. Vor allem gefördert werden Pro- Werk und Wirkung beleuchten Sir Antonio Pappano und den Brucknerfans werden von den jekte mit interdisziplinärem und lassen, ist uns dies – wie ich Bamberger Symphonikern unter Darbietungen der sinfonischen digitalem Schwerpunkt. glaube – eindrucksvoll gelungen. Jakub Hrůša sind etwa Gesangs- ebenso wie der kammermusika- Als Linzer*innen können wir zu Dadurch konnten wir auch die stars wie Waltraud Meier, Gün- lischen Kompositionen von Gus- Recht stolz auf Anton Bruckner Auslastung markant steigern, ther Groissböck und Thomas tav Mahler und Hans Rott sowie sein. -

Cantate Concert Program May-June 2014 "Choir + Brass"

About Cantate Founded in 1997, Cantate is a mixed chamber choir comprised of professional and avocational singers whose goal is to explore mainly a cappella music from all time periods, cultures, and lands. Previous appearances include services and concerts at various Chicago-area houses of worship, the Chicago Botanic Garden’s “Celebrations” series and at Evanston’s First Night. antate Cantate has also appeared at the Chicago History Museum and the Chicago Cultural Center. For more information, visit our website: cantatechicago.org Music for Cantate Choir + Br ass Peter Aarestad Dianne Fox Alan Miller Ed Bee Laura Fox Lillian Murphy Director Benjamin D. Rivera Daniella Binzak Jackie Gredell Tracy O’Dowd Saturday, May 31, 2014 7:00 pm Sunday, June 1, 2014 7:00 pm John Binzak Dr. Anne Heider Leslie Patt Terry Booth Dennis Kalup Candace Peters Saint Luke Lutheran Church First United Methodist Church Sarah Boruta Warren Kammerer Ellen Pullin 1500 W Belmont, Chicago 516 Church Street, Evanston Gregory Braid Volker Kleinschmidt Timothy Quistorff Katie Bush Rose Kory Amanda Holm Rosengren Progr am Kyle Bush Leona Krompart Jack Taipala Joan Daugherty Elena Kurth Dirk Walvoord Canzon septimi toni #2 (1597) ....................Giovanni Gabrieli (1554–1612) Joanna Flagler Elise LaBarge Piet Walvoord Surrexit Christus hodie (1650) .......................... Samuel Scheidt (1587–1654) Canzon per sonare #1 (1608) ..............................................................Gabrieli Thou Hast Loved Righteousness (1964) .........Daniel Pinkham (1923–2006) About Our Director Sonata pian’ e forte (1597) ...................................................................Gabrieli Benjamin Rivera has been artistic director of Cantate since 2000. He has prepared and conducted choruses at all levels, from elementary Psalm 114 [116] (1852) ................................. Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) school through adult in repertoire from gospel, pop, and folk to sacred polyphony, choral/orchestral masterworks, and contemporary pieces. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 71, 1951-1952, Trip

S- ,'r^^-'<^- ^GyO\. -/ -L BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY HENRY LEE HIGGINSON 7 k. ^9 X 'illl ""^ .^^ l^ H r vm \f SEVENTY -FIRST SEASON 1951-1952 Carnegie Hall, New York ; RCA VICTOR RECORDS BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Recorded under the direction of Charles Munch Beethoven ** Symphony No. 7 Beethoven *"Gratulations" Minuet Berlioz *Beatrice and Benedict Overture Brahms Symphony No. 4 Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1, in G minor Soloist, Yehudi Menuhin Haydn Symphony No. 104 ("London") Ravel La Valse Schubert Symphony No. 2 Among the recordings under the leadership of Serge Koussevitzky Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 1, Mozart Eine kleine Nachtmusik; in F; Brandenburg Concerto No. Serenade No. 10, in B-Flat, K. 6, in B-Flat; Suite No. 1, in C; 361; Symphony No. 36, in C, K. Suite No. 4, in D 425, "Linz"; Symphony No. 39, in E-Flat, K. 543 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, in E- Flat» "Broica" ; Symphony No. 5, Prolcofleff Concerto No. 2, in G Minor, in C Minor, Op. 67; Symphony Op. 63, Heifetz, violinist; Sym- No. 9, in D Minor, "Choral" phony No. 5 ; Peter and the Wolf, Op. 67 , Eleanor Roosevelt, narrator Brahms Symphony No. 3, in F, Op. 90 Ravel Bolero; Ma M6re L'Oye Suite Haydn Symphony No. 92, in G, "Ox- ford"; Symphony No. 94, in G, Schuhert Symphony No. 8, in B Minor, "Unfinished" "Surprise" ; Toy Symphony Khatchaturian Concerto for Piano Tchaikovsky Serenade in C, Op. 48 and Orchestra, William Kapell, Symphony No. 4, in F Minor, Op. pianist 36; Symphony No. 5, in E Minor, Op.