Mission Command: a Timeless Weapon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operation Dragon STRIKE! What Is...Howz-E-Madad? 2-BSTB's Combat Engineers

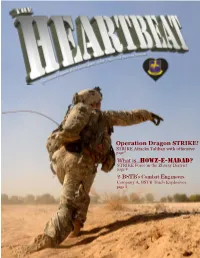

Operation Dragon STRIKE! STRIKE Attacks Taliban with offensive page7 What is...Howz-E-Madad? STRIKE Force in the Zharay District page 9 2-BSTB’s Combat Engineers Company A, BSTB Teach Explosives page 5 Table of Contents... 2 COLUMNS 2 Words From the Top A message to the reader from STRIKE’s Leaders, 5 Col. Arthur Kandarian and Sgt. Maj. John White. 3 The Brigade’s Surgeon & Chaplain Direction provided by the Lt. Col. Michael Wirt and Maj. David Beavers. 4 Combat Stress, The Mayor & Safety 6 Guidance, direction and standards. FEATURES 5 Engineers, Infantry & Demolition 7 2-BSTB’s Alpha Company teaches the line units explosives 6 ANA gets behind the wheel Soldiers send the ANA through driver’s training Coverpage!! 7 Operation Dragon STRIKE Combined Task Force STRIKE attacksTaliban. 9 9 What is… Howz-E-Madad? A look at STRIKE Force and its Foward Operating Base. Staff Sgt. James Leach, a platoon 11 Company D, 2nd Five-Oh-Deuce sergeant with 1/75’s HHT, points Dog Company stays together during deploying. at enemy positions while in a fire fight during an objective for Opera- STRIKE SPECIALS tion Dragon STRIKE 13 Faces of STRIKE Snap-shots of today’s STRIKE Soldiers 11 14 We Will Never Forget STRIKE honors its fallen. 13 CONTRIBUTORS OIC Maj. Larry Porter Senior Editor Sfc. William Patterson Editor Spc. Joe Padula 14 Staff Spc. Mike Monroe Staff Pfc. Shawn Denham The Heartbeat is published monthly by the STRIKE BCT Public Affairs Office, FOB Wilson, Afghanistan, APO AE 09370. In accordance with DoD Instruction 5120.4 the HB is an authorized publication of the Department of Defense. -

SP's Land Forces February-March 2011

February-March 2011 Volume 8 No 1 R `100.00 (India-based Buyer Only) SP GUIDE PUBLICATIONS SP’s AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION MEET US AT HALL E, BOOTH 22 AT AERO INDIA 2011 WWW.SPSLANDFORCES.NET ROUNDUP IN THIS ISSUE The ONLY journal in Asia dedicated to Land Forces PAGE 4 >> INTERVIEW Meeting the Challenges The Army Aviation is the arm of the future, a force-multiplier which can tilt the balance in any future conflict ‘Army Aviation Corps is the Lt General (Retd) B.S. Pawar PAGE 6 Past, Present and the Future Arm of the F uture’ PHOTOGRAPHS : Abhishek / SP Guide Pubns SP’s Land Forces (SP’s): What is the role of the Army Aviation? ADG Army Aviation (ADG) : Army Avia - tion operates in the ground regime, therefore it is virtually a component of the land power. This cardinal tenet defines Army Aviation’s role as an ele - ment of the ground forces. In the future battle field, Army Aviation will be at the Armaments used in helicopters can be forefront, shaping the battle space by pro - broadly classified into three categories, jecting the force, sustaining the force and namely rapid firing automatic machine guns, delivering decisive combat power at criti - rocket projectiles and guided missiles cal times anywhere in the battle field by direct fire, by launching air assaults or by Air Marshal (Retd) B.K. Pandey directing artillery fires. Its focus is to enhance ground mobility and exploit PAGE 10 manoeuvre. It accelerates the tempo of operations while remaining an integral A Long Way to Go part of the combined arms team. -

Global Threat Assessment for 2011*

Volume 3 Issue 1 January 2011 Global Threat Assessment for 2011* In this article, Professor Rohan Gunaratna, the Head of the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR), gives an assessment of preeminent security threat faced by key countries and regions in 2011. Inside this i s s u e : *This is an excerpt of the article written by the author for INSITE Magazine, a service of the SITE Intelligence Group. The full article can be accessed at https://insite.siteintelgroup.com/index.php Global Threat 1 Assessment for 2011 Southeast Asia Country 5 Assessments South Asia Country 14 Assessments Central and East Asia Country 28 Assessments Middle East and North Africa 32 Country Image Credit: Free Vector World Maps Collection Assessments http://www.webresourcesdepot.com/free-vector-world-maps-collection/ Letter from the 36 Transnational terrorism is likely to remain ghanistan, both in combat and support Editors the most profound threat in 2011. Politi- roles, to return home due to the decreas- About us 37 cally motivated groups that seek to legiti- ing public support for the war and domestic mize their thinking and actions by using, political considerations. Events and 37 misusing and misinterpreting the religious Global terrorism will be driven and Publications text , will continue to dominate the global sustained largely by the geopolitical pres- threat landscape. While homegrown and sures and developments in the Middle group terrorism are likely to remain at the East and Asia. In particular, four regions- forefront, homegrown terrorism in particu- Pakistan and Afghanistan, the Levant- lar will continue to be a formidable chal- Arabian Peninsula, the Horn of Africa, and lenge for security. -

STRIKE HISTORY” 16 September – 22 September 2012

2nd BCT, 101st ABN DIV (AASLT) “STRIKE HISTORY” 16 September – 22 September 2012 16 September – 06 December 2010 CTF STRIKE conducted a major operation involving all of its assets called Operation Dragon Strike. The operation was intended to provide security to southern Afghanistan. “Operation Dragon Strike is one of many operations designed to secure the majority of the Afghan population in the Zharay and Maiwand districts,” said COL Arthur Kandarian, CTFS commander. As the operation continues, the amount of attacks on Highway 1 has decreased, said Kandarian. The operation has each unit assigned to the 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), clearing Taliban strongholds along Kandahar’s busiest route. Highway 1 was considered Taliban property, but since the operation started, control has been given back to the populace. “Since Operation Dragon Strike began, we have seen an increase of the freedom of movement for the Afghan people on Highway 1,” said Kandarian. “We have also seen an increase in the amount of elders and leaders that come to the district center and we have been able to have the district governor go to more of the villages and places in the district to conduct shuras with the locals.” North of Highway 1 is desert terrain with a lower population whereas the southern part of the highway is a combination of populated villages, deep water canals, large grape fields, mountain chains and Taliban presence. Partnered patrols from the STRIKE Battalions and the Afghan National Army’s 205th Corps, over 8,000 strong, continues to take out key Taliban positions. -

Afghanistan Report 7

December 2010 Carl Forsberg AFGHANISTAN REPORT 7 COUNTERINSURGENCY IN KANDAHAR EVALUATING THE 2010 HAMKARI CAMPAIGN Cover Photograph: Canadian soldiers of the 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, along with Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police, took part in a partnered dismounted patrol around the Panjwai’i District in Kandahar province, Oct. 7, 2010. Photo Credit: Sgt. Richard Andrade, 16th Mobile Public Affairs Detachment All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2010 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2010 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Carl Forsberg AFGHANISTAN REPORT 7 COUNTERINSURGENCY IN KANDAHAR EVALUATING THE 2010 HAMKARI CAMPAIGN ABOUT THE AUTHOR Carl Forsberg, a research analyst at the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), specializes in the security dynamics and politics of southern Afghanistan. Mr. Forsberg is the author of two reports on Kandahar Province, The Taliban's Campaign for Kandahar and Politics and Power in Kandahar, which together offer an authoritative analysis of the strategic importance of Kandahar, the nature and objectives of the Taliban insurgency, and the challenges that regional politics pose to successful counterinsurgency. Mr. Forsberg has presented his findings on Kandahar in congressional testimony, at a weekly Pentagon forum attended by high-level experts and military officials, and at the U.S. -

The Kukri 2008

THE KUKRI 2008 The Kukri U B I Q U E NUMBER 60 The Journal of The Brigade of Gurkhas 2008 Design: HQLF(U) Design Studio © Crown Copyright Job Reference Number DS 14982 The Kukri - The Journal of The Brigade of Gurkhas The Kukri NUMBER 60 December 2008 (All rights reserved) Headquarters Brigade of Gurkhas Airfield Camp, Netheravon SP4 9SF United Kingdom The Journal of The Brigade of Gurkhas 2008 U B I Q U E Front Cover Queen’s Gurkha Orderly Officers Capt Khusiman Gurung RGR and Capt Sovitbahadur Hamal Thakuri QOGLR 1 The Kukri - The Journal of The Brigade of Gurkhas The Kukri - The Journal of The Brigade of Gurkhas Contents Number 60 December 2008 Editorial ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Report to the Right Honourable Doctor Ram Baran Yadav, President of the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal …………………………………………………………… 8 Honours and Awards ……………………………………………………………………………………… 11 Operations 1 RGR Commanding Officer’s Haul-Down Report ……………………………………………………………… 13 Air Operations with Regional Battle Group (South) on Op HERRICK 7 ……………………………… 18 Under the Influence? Thoughts on Influence at Platoon Level from Op HERRICK 7 …………………… 20 2 RGR Operations in Afghanistan - The First Three Months …………………………………………………… 22 Op HERRICK 9 – 2 RGR Battle Group (North West): Influence………………………………………… 31 Op KAPCHA BAZ ……………………………………………………………………………………… 37 Op GALLIPOLI STRIKE 1 ………………………………………………………………………………… 37 Raid North of Patrol Base WOQAB …………………………………………………………………… 38 QGE ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 42 QGS Stafford-based Gurkha Signallers -

Victory on Highway 1: Breaking the Taliban's Stranglehold in Kandahar

Combat Studies Institute Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Victory on Highway 1: Breaking the Taliban’s Stranglehold in Kandahar In July 2010, GEN David Petraeus, the commander of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan, designated the 2d Brigade Combat Team (2 BCT), 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) as ISAF’s main effort. Commanded by COL Arthur Kandarian, the brigade was responsible for conducting offensive operations in Kandahar Province’s Zhari District, the birthplace of the Taliban. Since 2006, when a Canadian-led task force defeated a large concentration of Taliban fighters preparing to assault nearby Kandahar city, the Taliban had reasserted control over Zhari. They assassinated key tribal elders, established a shadow government, erected the Taliban’s de facto “Supreme Court,” and persecuted political prisoners in torture compounds. Economically, the Taliban had a stranglehold over commerce. On Highway 1, the major thoroughfare connecting Helmand Province to the west with the city of Kandahar to the east, the Taliban set up illegal checkpoints throughout Zhari, stopping traffic and demanding exorbitant tolls. Drivers who refused to pay were swiftly ambushed by insurgents staging out of the jungle-like terrain south of the highway. With a growing insurgency on its western doorsteps, the second largest city in Afghanistan teetered on the brink of anarchy, political instability, and economic uncertainty. In order to break the insurgency’s iron grip on Highway 1, COL Kandarian planned a series of synchronized offensive operations south of the highway. Christened as Operation DRAGON STRIKE, the plan involved the 2 BCT’s two organic maneuver battalions (1st Battalion, 502d Infantry Regiment [1-502 IN] and 2d Battalion, 502d Infantry Regiment [2-502 IN]) and its Reconnaissance, Surveillance and Target Acquisition (RSTA) squadron (1st UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Squadron, 75th Cavalry Regiment [1-75 CAV]) clearing the insurgent-dominated terrain south of Highway 1. -

Global Threat Assessment for 2011*

Volume 3 Issue 1 January 2011 Global Threat Assessment for 2011* In this article, Professor Rohan Gunaratna, the Head of the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR), gives an assessment of preeminent security threat faced by key countries and regions in 2011. Inside this i s s u e : *This is an excerpt of the article written by the author for INSITE Magazine, a service of the SITE Intelligence Group. The full article can be accessed at https://insite.siteintelgroup.com/index.php Global Threat 1 Assessment for 2011 Southeast Asia Country 5 Assessments South Asia Country 14 Assessments Central and East Asia Country 28 Assessments Middle East and North Africa 32 Country Image Credit: Free Vector World Maps Collection Assessments http://www.webresourcesdepot.com/free-vector-world-maps-collection/ Letter from the 36 Transnational terrorism is likely to remain ghanistan, both in combat and support Editors the most profound threat in 2011. Politi- roles, to return home due to the decreas- About us 37 cally motivated groups that seek to legiti- ing public support for the war and domestic mize their thinking and actions by using, political considerations. Events and 37 misusing and misinterpreting the religious Global terrorism will be driven and Publications text , will continue to dominate the global sustained largely by the geopolitical pres- threat landscape. While homegrown and sures and developments in the Middle group terrorism are likely to remain at the East and Asia. In particular, four regions- forefront, homegrown terrorism in particu- Pakistan and Afghanistan, the Levant- lar will continue to be a formidable chal- Arabian Peninsula, the Horn of Africa, and lenge for security. -

The Maneuver Force in Battle 2005-2012

THE MANEUVER FORCE IN BATTLE 2005-2012 MANEUVER CENTER OF EXCELLENCE FORT BENNING, GEORGIA OCTOBER 2015 THE MANEUVER FORCE IN BATTLE 2005-2012 The Soldier is the Army. No army is better than its soldiers. The Soldier is also a citizen. In fact, the highest obligation and privilege of citizenship is that of bearing arms for one’s country. — General George S. Patton, Jr. October 2015 Maneuver Center of Excellence Fort Benning, Georgia 2015 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ I EDITOR’S NOTES ................................................................................................... III CHAPTER 1 MISSION COMMAND........................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 2 LEADERSHIP ...................................................................................11 CHAPTER 3 TEMPO ...........................................................................................35 CHAPTER 4 INTELLIGENCE................................................................................52 CHAPTER 5 RECONNAISSANCE .........................................................................67 CHAPTER 6 COMBINED ARMS ...........................................................................79 CHAPTER 7 TERRAIN ........................................................................................99 CHAPTER 8 MANEUVER ..................................................................................115 CHAPTER 9 TACTICAL PATIENCE ....................................................................147 -

VFW Post 5864 Newsletter 1842 Veterans Way, Greenwood, in 46143 – Phone 317-888-2488

VFW Post 5864 Newsletter 1842 Veterans Way, Greenwood, IN 46143 – Phone 317-888-2488 Greenwood Memorial VFW Post 5864 – September 2020 Newsletter "It’s not the dues you pay to be a member, it’s the price you paid to be eligible!” “Like us” on --Facebook -- Greenwood VFW 5864-- and visit our --Website-greenwoodvfw.com— 2017 and 2018 VFW First Place Award winner in the District / Post level for “Large e Frequency” Publications. 2019 Silver Award winner at the District / Post level l _____________________________________________________________________ VFW Post 5864 Auxiliary to host 9-11 luncheon Greenwood VFW Post 5864 Auxiliary will host a “9-11 Remembrance Luncheon” for Greenwood city workers to include all departments on Thursday, Sept. 10 from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. The luncheon is in remembrance and honor to the nearly 3,000 people killed in the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 at the World Trade Center site; near Shanksville, Pa.; and at the Pentagon, as well as the six people killed in the World Trade Center bombing in Feb. 1993. The meal will consist of fried chicken, mashed potatoes and gravy, beef and noodles, corn, green beans, rolls, butter, and assorted desserts. Upwards of 100 to 150 city workers will stop by for lunch. The VFW is located at 1842 Veterans Way in Greenwood. Go east on main St., under I-65, past the Road Ranger Truck Stop and turn right at the first street – Commerce Parkway Dr. West approximately 200 yards and the VFW is on the right. Any questions can be directed to the Post at 317-888-2488. -

STRIKE Changes Command

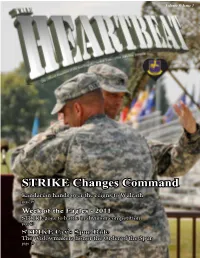

Volume 5, Issue 1 STRIKE Changes Command Kandarian hands over the reigns to Walrath page 19 Week of the Eagles - 2011 STRIKE goes to battle in division competition page 23 STRIKE Cav’s Spur Ride The Widowmakers honor the Order of the Spur page 39 Table of Contents... COLUMNS 2 2 Words From the Top 19 A message from STRIKE’s Col. Dan Walrath & Command Sgt. Maj. Alonzo Smith 3 The Brigade’s Surgeon & Chaplain Direction provided by the brigade’s medical staff and unit ministry team 4 Physical Therapy & STRIKE FRG Guidance, instructions and standards 5 STRIKE BOSS & Safety 9 Information for Single Soldiers and safety tips for the brigade Coverpage!! 6 Retention & Equal Opportunity Col. Arthur Kandarian, outgoing Strike com- Re-enlistment updates and vital EO info mander and Col. Dan Walrath, commander, FEATURES 2nd BCT, embrace each other during 9 STRIKE Iron Challenge Strike’s Change of STRIKE battalions compete for monthly top honors Command Ceremony on Fort Campbell’s 12 Marriage Retreat for STRIKE couples division parade field, Unit Ministry Teams hold retreat in Nashville for Soldiers and spouses July 15 13 Top Gun Soldier Halts Serial Robber Strike Soldier helps tackle local problem in Clarksville 19 STRIKE Changes Command Col. Arthur Kandarian hands over the Strike reigns to Col. Dan Walrath 23 Week of the Eagles 2011 13 Full coverage of Strike during the division wide competition 33 Former NFL Star Talks Resiliency to STRIKE 12 33 Herschel Walker provides guidance to Top Gun listeners 23 35 STRIKE Force Rides for its Fallen 2nd Battalion honors their fallen during motorcycle ride 36 STRIKE 6 PT 35 Col. -

“STRIKE HISTORY” 15 September – 21 September 2013

2nd BCT, 101st ABN DIV (AASLT) “STRIKE HISTORY” 15 September – 21 September 2013 15 – 17 September 1968 1-502 continued RIF operations, Rome plow operation, and security of An LO Bridge. The enemy was evasive and there were only two light sniper contacts, with negative assessment. The units continued to encounter BBT and find small caches. 15 September – 16 October 1968 1-327 Inf and 2-502 Inf conducted an airmobile combat assault into the Dong Truoi Mountain south of Hue. For the next 32 Days, the two battalions conducted extensive company-size RIF operations to locate and destroy the enemy forces indicated to be in the area. The combat assault of the two battalions was conducted in response to an increasing number of agent and sniffer reports, which indicated the enemy’s presence in the Dong Truoi Mountains (YD8097). In addition interrogation of the large number of PW’s and Hoi Chanhs gathered by the 2nd BDE during its cordon operations in Vinh Loc, confirmed the presence of five infantry battalions of the 4th and 5th NVA Regiments in the Truoi Mountains area. During the period 15 Sept – 16 Oct, the two battalions maintained continuous pressure on the enemy forces and, during the frequent contacts with squad to platoon size enemy forces, killed 78 NVA and captured 11 POW’s, 32 individual weapons, and 3 crew-served weapons. This operation served to keep at least five enemy battalions off balance and caused them to displace towards the southwest, thus relieving pressure on Da Nang, on OL #1 form Phu Bai to Hai Van Pass, and on Phu Loc District.