ROBERT SILVERMAN Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 24—31, 2016

new orleans international piano Competition XTHIRTY-FOURXTH KEYBOARDV FESTIVALI SEVENTEENTH PIANO INSTITUTE JULY 24—31, 2016 Competition Jury Peter Collins Danny Driver Faina Lushtak Marianna Prjevalskaya Nelita True Daniel Weilbaecher, chair Presented by the P.O. BOX 750698 • NEW ORLEANS, LA 70175-0698 • masno.org CARA MCCooL WooLF, Executive Director DANIEL WEILBAECHER, Artistic Director HOSTED BY LOYOLA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC STEINWAY & SONS the Official Piano of the New Orleans International Piano Competition — 2016 New Orleans International Piano Competition 11 steinway society 7-16_Layout 1 6/30/16 3:55 PM Page 1 S T E I N W A Y The Official Piano of the New Orleans International Piano Competition From piano competitions for scholarships to providing Special musical and social events throughout the year, The Steinway Society of New Orleans works to further musical appreciation and education. Musical patrons across Louisiana have come together in advancing the musical arts for all ages. As a member of the Steinway Society of New Orleans you join an exceptional circle of friends. For more information call 1-800-STEINWAY, and join with us as we support the Arts and Artists of our communities. S TEINWAY SOCIE TY New Or leans 1-800-SofTEINWAY Schedule of Events 4 T A Welcoming Messages 7–16 B LE MASNO History 17 O MASNO Board of Directors/Competition Committees 18 F C Guest Artists and Recital Programs 20–23 Danny Driver 20–21 on Marianna Prjevalskaya 22–23 TE Competition Prizes 25 N TS Competition Jurors 26–28 Peter Collins 26 -

Pianist Robert Silverman January 11, 2011 at 7:30 P.M., Tanna Schulich Hall

Schulich School of Music of McGill University Concerts and Publicity 555 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal, Quebec H3A 1E3 Phone: (514) 398-8101; Fax: (514) 398-5514 P R E S S R E L E A S E Pianist Robert Silverman January 11, 2011 at 7:30 p.m., Tanna Schulich Hall For immediate release Montreal, January 4, 2011 – Pianist Robert Silverman will give a recital at Tanna Schulich Hall on Tuesday January 11, 2011 at 7:30 p.m. as part of the McGill Staff and Guests Series. This concert will mark the 50th anniversary of the artist’s first professional concert engagement which took place in Montréal on January 15, 1961. Tickets are 10$. Program: For this occasion, Robert Silverman prepared a program comprising of four Opus 22 by Beethoven, Prokofiev, Schumann and Chopin. All four works mark a milestone for their composer: Beethoven wrote his as he began going deaf. Prokofiev launched his career as a performer and a composer with early piano works such as his Opus 22. By the time Schumann composed his, he had given up his ambition to become a concert pianist due to an injury to his hand. Finally, Chopin wrote his Opus 22 shortly after he arrived in Paris, where he spent the majority of his life. Bioghraphy: In a career spanning more than five decades, Robert Silverman has climbed every peak of serious pianism: lauded performances of the complete sonata cycles by Beethoven and Mozart; concerts in prestigious halls across the globe; orchestral appearances with many of the world’s greatest conductors; and award-winning recordings distributed internationally. -

Faculty 2016

Faculty 2016 DOROTHEA HAYLEY, VOICE ALEJANDRO OCHOA, PIANO ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Praised for her “very personal creative power,” Dorothea Alejandro Ochoa graduated Magna cum Laude from Hayley has been a soloist with the Vancouver Symphony, the Universidad de Los Andes, where his final recital the Bourgas Symphony and Capriccio Basel, and has was awarded the Otto de Grieff National Prize. As appeared in recital in Europe, Asia and North and South well as performing extensively throughout Colombia, America. She has performed in festivals such as the Alejandro has given solo and chamber music recitals Happening Festival, Gulangyu Piano Festival, New York in Canada, Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium and City Electroacoustic Music Festival and the Atempo Festival of Caracas, Portugal. Named the top competitor at the Concurso Nacional de Piano and with organizations like Vancouver New Music, the SMCQ, Chants Libres, UIS (2002), Alejandro is the recipient of numerous other prizes, including CIRMMT, Codes d’accès, and the Land’s End Ensemble. Dorothea completed the Berlind/Sara Award, McGill University’s Schulich Scholarship, and vocal studies at McGill University, the University of British Columbia, and the grants from the Canada Council for the Arts and the McGill Alma Mater Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien. She holds a Doctor of Fund. Alejandro recently completed a Doctorate in Performance at Music degree from Université de Montréal. McGill University, where he also served as Instructor of Piano. REBECCA WENHAM, CELLO MANUEL LAUFER, PIANO Cellist Rebecca Wenham has been described as “a Manuel Laufer has appeared as soloist and chamber musical force of nature.” She has performed across musician in North America, South America, and Europe. -

The Jacques Hétu Fonds

The Jacques Hétu Fonds National Library Bibliothèque nationale of Canada du Canada THE JACQUES HÉTU FONDS Numerical List by Stéphane Jean Ottawa, 1999 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data National Library of Canada The Jacques Hétu fonds : numerical list [computer file] Issued also in French under title: Le fonds Jacques-Hétu, répertoire numérique. Includes indexes. Issued also in printed format on demand. Mode of access: National Library of Canada WWW site. Issued by: Music Division. CCG cat. no. SN3-323/1999E-IN ISBN 0-660-17735-8 1. Hétu, Jacques, 1938- --Archives--Catalogs. 2. Music--Canada-- Sources--Bibliography--Catalogs. 3. Musicians--Canada--Archives-- Catalogs. 4. National Library of Canada. Music Division--Archives-- Catalogs. I. Jean, Stéphane, 1964- II. National Library of Canada. Music Division. III. Title. ML136.O88H592 1999b 016.78’092 C99-900255-4 Cover: Soir d’hiver by Jacques Hétu, C4/15 Graphic design: Denis Schryburt ã Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada (1999), as represented by the National Library of Canada. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the National Library of Canada, Canada K1A 0N4. Cat. No. SN3-323/1999E-IN ISBN 0-660-17735-8 2 Jacques Hétu, 1984. Photograph: Takashi Seida. All rights reserved. Reproduction for commercial purposes is forbidden. 3 “...as far as my writing technique is concerned, I see no value in completely forsaking the old method of writing; I am trying to combine elements from the past and the present...”[tr]. -

The Programming of Orchestral Music by Canadian Composers, 1980-2005

The Programming of Orchestral Music by Canadian Composers, 1980‐2005 by Robert John Fraser B.Mus. (Music Ed.), Brandon University, 1990 Licentiate in Music, McGill University, 1990 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Musicology with Performance School of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts © 2008 by Robert John Fraser University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii The Programming of Orchestral Music by Canadian Composers, 1980‐2005 by Robert John Fraser B.Mus. (Music Ed.), Brandon University, 1990 Licentiate in Music, McGill University, 1990 Supervisory Committee Dr. Susan Lewis Hammond, Supervisor School of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts Christopher Butterfield School of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts Dr. Jennifer Wise, Outside Member Department of Theatre, Faculty of Fine Arts iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Susan Lewis Hammond, Supervisor School of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts Christopher Butterfield School of Music, Faculty of Fine Arts Dr. Jennifer Wise, Outside Member Department of Theatre, Faculty of Fine Arts Abstract This thesis catalogues performances of orchestral music written by Canadian composers, performed between 1980 and 2005 by six Canadian professional symphony orchestras (Victoria, Calgary, Winnipeg, London, Toronto and Montreal). This catalogue, referred to as the Main Repertoire Table (MRT), lists 1574 performances. Using the results of the MRT, I identify 63 composers who have contributed five or more works to the repertoire, and 44 composers who have had at least ten performances. I also identify 47 works that have been performed five times or more. -

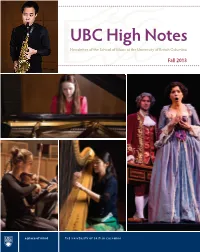

UBC High Notes Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia

UBC High Notes Newsletter of the School of Music at the University of British Columbia Fall 2013 Director’s Welcome On behalf of Richard Kurth, who is on leave this year before resuming his second term as Director, I am pleased to introduce the 15th edition of our yearly newsletter. It’s our chance to share with students, alumni, donors and supporters some of the great news about the UBC School of Music. We have worked diligently to solidify our position as the best place to study music in Western Canada and we are seeing the fruits of our efforts. Our concerts feature demanding repertoire and attract growing audiences. Our ensembles are showcased abroad: this year the University Singers toured Spain; the Opera Ensemble performed in Ontario and the Czech Republic; and the Symphonic Wind Ensemble gave performances and workshops throughout the U.S. West Coast. Numerous students have been recognized for their choral and instrumental compositions. I am especially proud to note that our students have also served as UBC Ambassadors to the Concerts in Care program, which provides pleasure and comfort to residents in health care facilities across Canada. Photo Credit: Varun Saran Our faculty members have made significant contributions to the world of music through innovative performances, original compositions and wide-ranging scholarship. They continue to refine our pedagogy by providing performance instruction in partnership with some of the best professional musicians in the city, familiarizing students with technology that every musician will need to use, and developing their theoretical and historical understanding. I hope this issue of High Notes shares the excitement and pride I feel about the accomplishments of this past year and our hopes for the future. -

The Lives of Glenn Gould: the Limits of Musical Auto/Biography

THE LIVES OF GLENN GOULD: THE LIMITS OF MUSICAL AUTO/BIOGRAPHY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH MAY 2012 BY ALANA BELL Dissertation Committee: Craig Howes, Chairperson Miriam Fuchs Glenn Man John Zuern E. Douglas Bomberger Lesley A. Wright KEYWORDS: GLENN GOULD, MUSIC, AUTOBIOGRAPHY, BIOGRAPHY i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I lived with this project for many years, and there are many people to thank. My advisor Craig Howes offered exactly the kind of support and encouragement I needed, which sometimes meant simply letting me live my life without the pressure to write. When I was ready and able to work, Craig put in many tireless hours (mostly over the telephone in true Glenn Gould style) to help me make my dissertation the best it could be. Craig’s knowledge of life writing is encyclopedic, and his understanding of Canadian culture and history is vast. Having grown up in Gould’s city, he offered fascinating and valuable first-hand accounts of twentieth-century Toronto. I cannot imagine a better teacher and mentor, and I am extremely grateful for his help. This dissertation represents the culmination of ideas formed through courses and conversations with each of my committee members. I developed the initial idea to investigate life writing about Glenn Gould in a course taught by Miriam Fuchs, one of several in which I gained theoretical knowledge and writing skills that were crucial to this project. I did some initial writing on Gould’s Goldberg Variations recordings in Douglas Bomberger’s keyboard literature course, and I did some early thinking about musical biography in his course on Robert Schumann. -

Viewed the Thesis/Dissertation in Its Final Electronic Format and Certify That It Is an Accurate Copy of the Document Reviewed and Approved by the Committee

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: April 29, 2009 I, Yoomi Jun Kim , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance It is entitled: The Evolution of Alexina Louie's Piano Music: Reflections of a Soul Searching Journey Yoomi Kim Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Joel Hoffman, DMA Eugene Pridonoff Elisabeth Pridonoff Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Joel Hoffman, DMA The Evolution of Alexina Louie’s Piano Music: Reflections of a Soul Searching Journey A document submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts In the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music April 2009 By Yoomi J. Kim [email protected] 2732 Sooke Road Victoria, BC V9B 1Y9 Canada BM, Peabody Conservatory of Johns Hopkins University, 1999 MM, University of Montreal, 2001 MM, University of Cincinnati (Choral Conducting), 2004 Committee Chair: Dr. Joel Hoffman ABSTRACT This document examines the piano music of Canada’s foremost contemporary art music composer Alexina Louie (b. 1949) who is repeatedly praised for drawing out virtuosic yet sonorous techniques and coloristic effects on the piano. The significance of investigating Louie’s music is reflected in the extensive articles, surveys, and doctoral theses. However, these previous studies focus largely on her exotic Asian influences as they are written before Louie’s new intentional stylistic changes in recent years which incorporate jazz and blues idioms. -

Angela Cheng and Alvin Chow, Piano 2012 Dorothy Morton Visiting Artists Series April 11-12, 2012

Schulich School of Music of McGill University Concerts and Publicity 555 Sherbrooke Street West, Montreal, Quebec H3A 1E3 Phone: (514) 398-8101; Fax: (514) 398-5514 P R E S S R E L E A S E Angela Cheng and Alvin Chow, piano 2012 Dorothy Morton Visiting Artists Series April 11-12, 2012 For immediate release Montreal, April 5, 2012 – Pianists Angela Cheng and Alvin Chow are the 2012 Dorothy Morton Visiting Artists at the Schulich School of Music. They can be heard in a concert of duo piano music on Wednesday, April 11 at 7:30 p.m. in Pollack Hall and will give a masterclass on Thursday, April 12 at 7:30 p.m. in Tanna Schulich Hall. Concert: Wednesday, April 11, 2012 at 7:30 p.m. in Pollack Hall, $10 general admission Complete Program: Johanne Brahms, Hungarian Dances Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5 Claude Debussy, Petite Suite Antonín Dvořák, Slavonic Dances, Op. 46, Nos. 4, 6, 8 Darius Milhaud, Scaramouche Aaron Copland, El Salón México Maurice Ravel, La Valse Masterclass: Thursday, April 12, 2012 at 7:30 p.m. in Tanna Schulich Hall, $10 general public (music students free) Angela Cheng, consistently cited for her brilliant technique, tonal beauty and superb musicianship, is one of Canada's brightest stars. She has appeared as soloist with virtually every orchestra in Canada, as well as the Birmingham Symphony, Buffalo Philharmonic, Colorado Symphony, Houston Symphony, Indianapolis Symphony, Jacksonville Symphony, Louisiana Philharmonic, Saint Louis Symphony, Syracuse Symphony, Utah Symphony and the Israel Philharmonic, among others. The frequency with which she is re-engaged is remarkable. -

Final Document 12-12-13 with Edited Appendices.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE AN OVERVIEW OF THE PIANO CONCERTO IN CANADA SINCE 1900 WITH STYLISTIC ANALYSES OF WORKS SINCE 1967 BY ECKHARDT-GRAMATTÉ, DOLIN, LOUIE, KUZMENKO, AND SCHMIDT A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By MICHELLE RUTHANNE PRICE Norman, Oklahoma 2013 AN OVERVIEW OF THE PIANO CONCERTO IN CANADA SINCE 1900 WITH STYLISTIC ANALYSES OF WORKS SINCE 1967 BY ECKHARDT-GRAMATTÉ, DOLIN, LOUIE, KUZMENKO, AND SCHMIDT A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ______________________________ Dr. Marvin Lamb, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Edward Gates, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Jane Magrath ______________________________ Dr. Sanna Pederson ______________________________ Dr. Teresa DeBacker © Copyright by MICHELLE RUTHANNE PRICE 2013 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgments I would like to thank my committee members for their tremendous support, advice, and valuable service to the betterment of my education. Special thanks go to my chair, Dr. Marvin Lamb, for his willingness to serve as coordinator and advisor for the final semester of my document research. To Dr. Jane Magrath, I express my sincere appreciation for her editing advice and guidance as my former chair for four years. I would like to especially thank my co-chair, Dr. Ed Gates, whose editing probed into the recesses of my mind and aided my growth as a researcher, scholar, critical thinker, and confident writer. Thank you to Dr. Sanna Pederson, for her input while in both Norman and abroad in Germany. Finally, thank you to Dr. Teresa DeBacker, for her supportive service and valuable feedback. -

Music on the Edge »

Brenda Ravenscro!, PhD Doyenne, École de musique Schulich Dean, Schulich School of Music J’ai le grand plaisir de vous souhaiter la bienvenue à It is my great pleasure to welcome you to Piano l’événement Autour du piano 2018 à l’École de musique Homecoming 2018 at the Schulich School of Music Schulich de l’Université McGill. Cette fin de semaine, of McGill University. This weekend, graduates, faculty, diplômés, professeurs et amis du piano se rassem- and friends of the piano will reconnect through con- blent pour des concerts, des cours de maître, des tables certs, master classes, panel discussions, and studio rondes et des occasions de retrouvailles : de la pédagogie reunions – from pedagogy to performances, the im- à l’interprétation, nos fabuleux talents s’affichent ! pressive talents of our piano community will be on full display! Les couloirs des pavillons Strathcona et Elizabeth Wirth résonnent de musique 365 jours par année, mais The hallways of the Strathcona and Elizabeth Wirth le moment des retrouvailles s’avère toujours excep- music buildings are alive with music-making 365 tionnel. Si les retrouvailles s’organisent habituelle- days a year, but Homecoming is always an extraordi- ment autour d’une promotion donnée, pour la toute nary time. Where reunions typically focus on a grad- première fois, c’est plutôt l’instrument qui crée l’événe- uation year, for the first time ever we’re highlighting ment – avec cet avantage non négligeable de relier des an instrument instead! In so doing, we have the en- générations de pianistes : étudiants actuels, diplômés viable advantage of connecting across generations of récents, anciens auréolés de prestige, tous peuvent pianists: current students, recent graduates, and es- célébrer les réussites passées et futures.