Sporting Traditions, Volume 16 Number 2, May 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1 PETER C. BJARKMAN www.bjarkman.com Cuban Baseball Historian Author and Internet Journalist Post Office Box 2199 West Lafayette, IN 47996-2199 USA IPhone Cellular 1.765.491.8351 Email [email protected] Business phone 1.765.449.4221 Appeared in “No Reservations Cuba” (Travel Channel, first aired July 11, 2011) with celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain Featured in WALL STREET JOURNAL (11-09-2010) front page story “This Yanqui is Welcome in Cuba’s Locker Room” PERSONAL/BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Born: May 19, 1941 (72 years old), Hartford, Connecticut USA Terminal Degree: Ph.D. (University of Florida, 1976, Linguistics) Graduate Degrees: M.A. (Trinity College, 1972, English); M.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1970, Education) Undergraduate Degree: B.S.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1963, Education) Languages: English and Spanish (Bilingual), some basic Italian, study of Japanese Extensive International Travel: Cuba (more than 40 visits), Croatia /Yugoslavia (20-plus visits), Netherlands, Italy, Panama, Spain, Austria, Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala, Canada, Japan. Married: Ronnie B. Wilbur, Professor of Linguistics, Purdue University (1985) BIBLIOGRAPHY March 2014 MAJOR WRITING AWARDS 2008 Winner – SABR Latino Committee Eduardo Valero Memorial Award (for “Best Article of 2008” in La Prensa, newsletter of the SABR Latino Baseball Research Committee) 2007 Recipient – Robert Peterson Recognition Award by SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee, for advancing public awareness -

Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects by Daniel A

Sports, Culture, and Asia Baseball in Japan and the US History, Culture, and Future Prospects By Daniel A. Métraux A 1927 photo of Kenichi Zenimura, the father of Japanese-American baseball, standing between Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth. Source: Japanese BallPlayers.com at http://tinyurl.com/zzydv3v. he essay that follows, with a primary focus on professional baseball, is intended as an in- troductory comparative overview of a game long played in the US and Japan. I hope it will provide readers with some context to learn more about a complex, evolving, and, most of all, Tfascinating topic, especially for lovers of baseball on both sides of the Pacific. Baseball, although seriously challenged by the popularity of other sports, has traditionally been considered America’s pastime and was for a long time the nation’s most popular sport. The game is an original American sport, but has sunk deep roots into other regions, including Latin America and East Asia. Baseball was introduced to Japan in the late nineteenth century and became the national sport there during the early post-World War II period. The game as it is played and organized in both countries, however, is considerably different. The basic rules are mostly the same, but cultural differences between Americans and Japanese are clearly reflected in how both nations approach their versions of baseball. Although players from both countries have flourished in both American and Japanese leagues, at times the cultural differences are substantial, and some attempts to bridge the gaps have ended in failure. Still, while doubtful the Japanese version has changed the American game, there is some evidence that the American version has exerted some changes in the Japanese game. -

Scenery Baseball Postmarks of Japan

JOURNAL OF SPORTS PHILATELY Volume 51 Spring 2013 Number 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS President's Message Mark Maestrone 1 Cricket & Philately: Cricket on the Peter Street 3 Subcontinent – Bangladesh Hungary Salutes London Olympics Mark Maestrone 10 and Hungarian Olympic Team & Zoltan Klein 1928 Olympic Fencing Postcards from Italy Mark Maestrone 12 Scenery Baseball Postmarks Norman Rushefsky 15 of Japan & Masaoki Ichimura 100th Grey Cup Game – A Post Game Addendum Kon Sokolyk 22 The next Olympic Games are J.L. Emmenegger 24 just around the corner! Book Review: Titanic: The Tennis Story Norman Jacobs, Jr. 28 The Sports Arena Mark Maestrone 29 Reviews of Periodicals Mark Maestrone 30 News of our Members Mark Maestrone 32 New Stamp Issues John La Porta 34 www.sportstamps.org Commemorative Stamp Cancels Mark Maestrone 36 SPORTS PHILATELISTS INTERNATIONAL CRICKET President: Mark C. Maestrone, 2824 Curie Place, San Diego, CA 92122 Vice-President: Charles V. Covell, Jr., 207 NE 9th Ave., Gainesville, FL 32601 3 Secretary-Treasurer: Andrew Urushima, 1510 Los Altos Dr., Burlingame, CA 94010 Directors: Norman F. Jacobs, Jr., 2712 N. Decatur Rd., Decatur, GA 30033 John La Porta, P.O. Box 98, Orland Park, IL 60462 Dale Lilljedahl, 4044 Williamsburg Rd., Dallas, TX 75220 Patricia Ann Loehr, 2603 Wauwatosa Ave., Apt 2, Wauwatosa, WI 53213 Norman Rushefsky, 9215 Colesville Road, Silver Spring, MD 20910 Robert J. Wilcock, 24 Hamilton Cres., Brentwood, Essex, CM14 5ES, England Store Front Manager: (Vacant) Membership (Temporary): Mark C. Maestrone, 2824 Curie Place, San Diego, CA 92122 Sales Department: John La Porta, P.O. Box 98, Orland Park, IL 60462 OLYMPIC Webmaster: Mark C. -

Baseball and Beesuboru

AMERICAN BASEBALL IMPERIALISM, CLASHING NATIONAL CULTURES, AND THE FUTURE OF SAMURAI BESUBORU PETER C. BJARKMAN El béisbol is the Monroe Doctrine turned into a lineup card, a remembrance of past invasions. – John Krich from El Béisbol: Travels Through the Pan-American Pastime (1989) When baseball (the spectacle) is seen restrictively as American baseball, and then when American baseball is seen narrowly as Major League Baseball (MLB), two disparate views will tend to appear. In one case, fans happily accept league expansion, soaring attendance figures, even exciting home run races as evidence that all is well in this best of all possible baseball worlds. In the other case, the same evidence can be seen as mirroring the desperate last flailing of a dying institution – or at least one on the edge of losing any recognizable character as the great American national pastime. Big league baseball’s modern-era television spectacle – featuring overpaid celebrity athletes, rock-concert stadium atmosphere, and the recent plague of steroid abuse – has labored at attracting a new free-spending generation of fans enticed more by notoriety than aesthetics, and consequently it has also succeeded in driving out older generations of devotees once attracted by the sport’s unique pastoral simplicities. Anyone assessing the business health and pop-culture status of the North American version of professional baseball must pay careful attention to the fact that better than forty percent of today’s big league rosters are now filled with athletes who claim their birthright as well as their baseball training or heritage outside of the United States. -

From Ppēsŭppol to Yagu: the Evolution of Baseball and Its Terminology in Korea

FROM PPĒSŬPPOL TO YAGU: THE EVOLUTION OF BASEBALL AND ITS TERMINOLOGY IN KOREA by Natasha Rivera B.A., The University of Minnesota, 2010 M.A., SOAS, University of London, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2015 © Natasha Rivera, 2015 Abstract Baseball has shaped not only the English language, but also American society. From the early development of professional sport, to spearheading integration with Jackie Robinson’s first appearance, to even deploying “baseball ambassadors” in Japan as wartime spies, baseball has been at the forefront of societal change even as its popularity declined in the United States. Nonetheless, the sport’s global presence remains strong, presenting us with an opportunity to examine how baseball has shaped language and society outside North America. Baseball has an extensive set of specialized terms. Whether these words are homonyms of other English terms, or idioms unique to the sport, each term is vital to the play of the game and must be accounted for when introducing baseball to a new country. There are various ways to contend with this problem: importing the terms wholesale as loanwords, or coining neologisms that correspond to each term. Contemporary Korean baseball terminology is the still-evolving product of a historically contingent competition between two sets of vocabulary: the English and the Japanese. Having been first introduced by American missionaries and the YMCA, baseball was effectively “brought up” by the already baseball-loving Japanese who occupied Korea as colonizers shortly after baseball’s first appearance there in 1905. -

Title Foucauldian Theory and the Making of the Japanese Sporting Body Author(S) Miller, Aaron L. Citation Contemporary Japan

Foucauldian theory and the making of the Japanese sporting Title body Author(s) Miller, Aaron L. Citation Contemporary Japan (2015), 27(1): 13-31 Issue Date 2015 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235680 © 2015 Aaron L. Miller. This work is licensed under the Right Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University DOI 10.1515/cj-2015-0002 Contemporary Japan 2015; 27(1): 13–31 Open Access Aaron L. Miller Foucauldian theory and the making of the Japanese sporting body Abstract: International sporting competitions, such as the upcoming 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, adhere to a nationalistic and triumphalist paradigm in which strength, victories, and medals are judged more important than anything else. Within this paradigm, what matters most is which sporting body can subdue another. National sporting consciousnesses often reflect this paradigm, and the case of Japan offers no exception. How do international power relations within such paradigms shape sporting bodies, national sports consciousnesses, and our knowledge of them? To answer this question, this paper applies the theory of Michel Foucault to a historical study of Japanese sports. By applying Foucault’s theory of power, especially his ideas of “bio-power” and the “productive” nature of “power relations,” we can better interpret historical shifts in the way Japanese have perceived their sporting bodies over time, especially the view that the Japanese sporting bodies are unique but inferior when compared with non-Japanese sporting bodies. International power relations and perceptions of cultural inferiority weigh heavy on Japanese sporting bodies. They produce certain behaviors, such as the action of toeing the line for one’s team, especially when that team is the nation, and certain discourses, such as the narrative that Japanese sporting bodies must train together to best play together. -

War Me Baseball in Hawaii

Wounded in Combat in Hawaii in Warme Baseball Warme 1941: Calm Before the Storm the Calm Before 1941: Baseball in Wartime Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 50 June 2020 Wartime Baseball in Hawaii For more than a quarter of a century I’ve been researching and writing about wartime baseball. It’s a subject that continues to fascinate me and one that unlocks new discoveries on an almost daily basis. Recently, I’ve turned my attention to baseball in Hawaii during World War II. I’ve always been aware that many big league players were stationed in Hawaii but what about the structure of military baseball? The teams? The leagues? I decided it was time to put the pieces together, especially because I could find no definitive source that had actually done so. So, here it is, the first of five newsletters covering the war years in Hawaii, 1941 to 1945. This issue – 1941: Calm Before the Storm – deals with the year of the infamous Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that thrust the United States into war. As you will see, there was plenty of baseball in Hawaii in 1941 – a lack of major league names, obviously – Jim Helton (19th Inf. Regt) threw a no-hitter th but still an interesting introduction to against the 8 Field Artillery July 23, 1941 what was to come. I hope you enjoy this first issue. The others will follow in the coming Gary Bedingfield weeks and months, and if you have Don’t forget to visit my websites! anything you’d care to add for the www.baseballinwartime.com years 1942 to 1945, then you know www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com where to find me. -

Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer

Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer Bill STAPLES, Jr. INTRODUCTION (After showing the opening sequence of the NHK Documentary on Zenimura) Hello, my name is Bill Staples. I am a baseball historian and author of the book, Kenichi Zenimura, Japanese American Baseball Pioneer. It is an honor to be here today to discuss the life and legacy of Zenimura-san. Before I start, I would like to thank the representatives from Ritsumeikan University for inviting me to Japan. Specifically, I want to thank Kyoko Yoshida, a fellow baseball historian who I have collaborated with on baseball research projects since 2006. Amazingly, this is our first time to meet in person. I would also like to thank the distinguished faculty of the International Institute of Language and Culture Studies and its staff members: Prof. Takahashi, Mr. Yasukawa, Ms. Shiga, and Mr. Shimizu. I would also like to thank the three panelists joining us today at our symposium: Mr. Ishihara, Mr. Takano, and Mr. Masaki. For me to tell you the story of Zenimura I first have to tell you a little about myself, as I feel our life stories are now intertwined. I fell in love with the game of baseball at age 10. I lived in Houston, Texas, at the time and the Astros were my favorite team. If you would have told me then that the Astros would win the World Series in 2017, and that I would travel to Japan to talk about baseball history several months later, I would not have believed you. My interest in Japanese culture began 30 years ago. -

The Power and Limitations of Baseball As a Cultural Instrument of Diplomacy in Us-Japanese Relations

THE POWER AND LIMITATIONS OF BASEBALL AS A CULTURAL INSTRUMENT OF DIPLOMACY IN US-JAPANESE RELATIONS A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By David Goto McCagg, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. March 31, 2015 THE POWER AND LIMITATIONS OF BASEBALL AS A CULTURAL INSTRUMENT OF DIPLOMACY IN US-JAPANESE RELATIONS David Goto McCagg, B.A. MALS Mentor: Ralph Nurnberger, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Almost from the opening of Japan to the West in the mid-nineteenth century, baseball has been used by both the governments of Japan and the United States to further their national aims—whether those aims were to wage peace or wage war. Team work, fair play, dedication to improvement through practice, pursuit of physical well-being, competition, respect for authority and the law (or the rules of the game) are all concepts that can apply both to playing baseball and to being good citizens and good neighbors. The history of baseball in Japan, viewed within the context of US-Japanese relations, is an illuminating case study of how sports, politics, and diplomacy can interact because it spans the entire history of the relationship and touches on both the positive and negative aspects of sports diplomacy. In fact, the history of baseball in Japan generally mirrors the history of US-Japanese relations. Through baseball, transpacific friendships have been forged, negative perceptions of foreigners in Japan decreased, and the morale of a nation was restored. -

Baseball in Wartime Website and Also the Baseball in Wartime Blog, I JAMES G

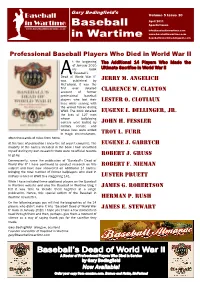

Gary Bedingfield’s Baseball Volume 5 Issue 30 April 2011 in Wartime Baseball Special Issue www.baseballinwartime.com [email protected] www.baseballinwartime.com in Wartime baseballinwartime.blogspot.com Professional Baseball Players Who Died in World War II t the beginning The Additional 14 Players Who Made the of January 2010 my book Ultimate Sacrifice in World War II “Baseball’s ADead of World War II” was published by JERRY M. ANGELICH McFarland. It was the first ever detailed account of former CLARENCE W. CLAYTON professional baseball players who lost their LESTER O. CLOTIAUX lives while serving with the armed forces during WWII. The book detailed EUGENE L. DELLINGER, JR. the lives of 127 men whose ballplaying careers were halted by JOHN H. FESSLER military service and whose lives were ended in tragic circumstances, TROY L. FURR often thousands of miles from home. At the time of publication I knew the list wasn’t complete. The EUGENE J. GABRYCH majority of the names included in the book I had unearthed myself during my own research; there were no official records to go by. ROBERT J. GRUSS Consequently, since the publication of “Baseball’s Dead of World War II” I have continued to conduct research on this ROBERT F. NIEMAN subject and have now uncovered an additional 14 names, bringing the total number of former ballplayers who died in military service in WWII to a staggering 141. LUSTER PRUETT While I have included these additional players on the Baseball in Wartime website and also the Baseball in Wartime blog, I JAMES G. -

35 Cody Bellinger #54 Tony Cingrani #21 Yu Darvish #6 Curtis Granderson #58 Edward Paredes #33 Tony Watson

#35 CODY BELLINGER #54 TONY CINGRANI #21 YU DARVISH #6 CURTIS GRANDERSON #58 EDWARD PAREDES #33 TONY WATSON CODY BELLINGER // Infielder/Outfielder NON-ROSTER INVITEE 35 BATS: Left THROWS: Left HEIGHT: 6-4 WEIGHT: 213 OPENING DAY AGE: 21 ML SERVICE: 0.000 BORN: July 13, 1995 in Chandler, AZ RESIDES: Scottsdale, AZ ACQUIRED: Selected in the fourth round of the 2013 First-Year Player Draft CAREER HIGHLIGHTS • The 21-year-old power-hitting outfielder/first baseman enters his fifth professional season after being selected by the Dodgers in the fourth round of the 2013 draft • Has a career .271 batting average with a .501 slugging percentage, 77 doubles, 17 triples, 65 homers and 253 RBI in 361 AVILAN career games • Defensively, has appeared in 282 games at first base, 41 games in center field and 15 games in left during the course of his career • Selected as 2016 Baseball America’s Double-A All-Star and MiLB.com Organizational All-Star • Selected as a 2015 mid- and post-season California League All-Star after leading the league with 103 RBI and 97 runs scored, while placing second with 30 homers and batting .264 in 128 games…also honored as the MVP of the league championship series for the title-winning Quakes after batting .324 with three homers and seven RBI in eight postseason games • Selected by the Dodgers in the fourth round of the 2013 First-Year Player Draft YEAR-BY-YEAR 2017 (Prior to April 25) • Posted a .343 (23-for-67)/.429/.627 slashline with 15 runs, four doubles, five home runs, 15 RBI and seven stolen bases in 18 games with -

Out at Home: Challenging the United States-Japanese Player Contract Agreement Under Japanese Law, 33 Brook

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Brooklyn Law School: BrooklynWorks Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 33 Issue 3 SYMPOSIUM: Corporate Liability for Grave Article 9 Breaches of International Law 2008 Out at Home: Challenging the United States- Japanese Player Contract Agreement Under Japanese Law Victoria J. Siesta Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Victoria J. Siesta, Out at Home: Challenging the United States-Japanese Player Contract Agreement Under Japanese Law, 33 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2008). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol33/iss3/9 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. OUT AT HOME: CHALLENGING THE UNITED STATES-JAPANESE PLAYER CONTRACT AGREEMENT UNDER JAPANESE LAW INTRODUCTION lthough it is an inherently American game, thus dubbed the A “American Pastime,”1 baseball is no exception to globalization.2 For years, Major League Baseball (“MLB”) scouts have traversed South America, Latin America and the Caribbean in search of outstanding tal- ent.3 Moreover, players from across Asia have excelled in MLB for more than a decade.4 Indeed, the main reason that international players come to MLB is to prove their skills in the world’s premiere baseball forum.5 In- 1. Casey Duncan, Note, Stealing Signs: Is Professional Baseball’s United States- Japanese Player Contract Agreement Enough to Avoid Another “Baseball War”?, 13 MINN. J. GLOBAL TRADE 87, 88 (2003).