Parent Handbook 2020-2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Private High Schools 1 2 3

2015/10/27 Best Private High Schools in Massachusetts Niche ὐ Best Private High Schools in Massachusetts Best Private High Schools ranks 3,880 high schools based on key student statistics and more than 120,000 opinions from 16,000 students and parents. A high ranking indicates that the school is an exceptional academic institution with a diverse set of high-achieving students who rate their experience very hRigehalyd. more See how this ranking was calculated. National By State By Metro See how your school ranks Milton Academy 1 Milton, MA Show details Deerfield Academy 2 Deerfield, MA Show details Groton School 3 Groton, MA Show details Middlesex School 4 Concord, MA Show details Noble & Greenough School 5 Dedham, MA Show details https://k12.niche.com/rankings/privatehighschools/bestoverall/s/massachusetts/ 1/13 2015/10/27 Best Private High Schools in Massachusetts Niche Winsor School 6 Boston, MA Show details Buckingham Browne & Nichols School 7 Cambridge, MA Show details Commonwealth School 8 Boston, MA Show details Boston University Academy 9 Boston, MA Show details James F. Farr Academy 10 Cambridge, MA Show details Share Share Tweet Miss Hall's School 11 Pittsfield, MA Show details The Roxbury Latin School 12 West Roxbury, MA Show details Stoneleigh Burnham School 13 Greenfield, MA Show details Brooks School 14 North Andover, MA Show details Concord Academy https://k12.niche.com/rankings/privatehighschools/bestoverall/s/massachusetts/ 2/13 2015/10/27 Best Private High Schools in Massachusetts Niche Concord, MA 15 Show details Belmont Hill School 16 Belmont, MA Show details St. -

North Shore Secondary School Fair

NORTH SECONDARY SHORE SCHOOL FAIR The Academy at Penguin Hall Lexington Christian Academy TUESDAY Avon Old Farms School Lincoln Academy TH Belmont Hill School Linden Hall SEPTEMBER 26 Berkshire School Loomis Chaffee School Berwick Academy Marianapolis Preparatory School 6:00-8:30 PM Bishop Fenwick High School Marvelwood School Boston University Academy Middlesex School Brewster Academy Millbrook School FREE & OPEN Brooks School Milton Academy The Cambridge School of Weston Miss Hall’s School TO THE PUBLIC Cate School Miss Porter’s School *Meet representatives CATS Academy New Hampton School Chapel Hill-Chauncy Hall School Noble and Greenough School and gather information Cheshire Academy Northfield Mount Hermon School Choate Rosemary Hall Phillips Academy from day, boarding Christ School Phillips Exeter Academy Clark School Pingree School and parochial schools. Commonwealth School Pomfret School Concord Academy Portsmouth Abbey School Covenant Christian Academy Proctor Academy Cushing Academy The Putney School HOSTED BY: Dana Hall School Saint Mary’s School Deerfield Academy Salisbury School BROOKWOOD SCHOOL Dublin School Shore Country Day School ONE BROOKWOOD ROAD Eaglebrook School Sparhawk School Emma Willard School St. Andrew’s School MANCHESTER, MA 01944 The Ethel Walker School St. George’s School 978-526-4500 Fay School St. John’s Preparatory School brookwood.edu/ssfair The Fessenden School St. Mark’s School Foxcroft Academy St. Mary’s School, Lynn Fryeburg Academy St. Paul’s School Garrison Forest School Stoneleigh-Burnham School -

An Open Letter on Behalf of Independent Schools of New England

An Open Letter on Behalf of Independent Schools of New England, We, the heads of independent schools, comprising 176 schools in the New England region, stand in solidarity with our students and with the families of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The heart of our nation has been broken yet again by another mass shooting at an American school. We offer our deepest condolences to the families and loved ones of those who died and are grieving for the loss of life that occurred. We join with our colleagues in public, private, charter, independent, and faith-based schools demanding meaningful action to keep our students safe from gun violence on campuses and beyond. Many of our students, graduates, and families have joined the effort to ensure that this issue stays at the forefront of the national dialogue. We are all inspired by the students who have raised their voices to demand change. As school leaders we give our voices to this call for action. We come together out of compassion, responsibility, and our commitment to educate our children free of fear and violence. As school leaders, we pledge to do all in our power to keep our students safe. We call upon all elected representatives - each member of Congress, the President, and all others in positions of power at the governmental and private-sector level – to take action in making schools less vulnerable to violence, including sensible regulation of fi rearms. We are adding our voices to this dialogue as a demonstration to our students of our own commitment to doing better, to making their world safer. -

SIMS Version 2.0 Data Standards Handbook for the Massachusetts Student Information Management System Reference Guide Version 3.3

SIMS Version 2.0 Data Standards Handbook for the Massachusetts Student Information Management System Reference Guide Version 3.3 October 1, 2004 Massachusetts Department of Education Page 1–2 SIMS Version 3.3 Student Data Standards October 1, 2004 SIMS Version 2.0 Data Standards Handbook for the Massachusetts Student Information Management System Reference Guide Version 3.3 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................................ 1–3 STUDENT INFORMATION MANAGEMENT SYSTEM ..................................................................................1–3 SECTION 2 STATE STUDENT REGISTRATION SYSTEM............................................................................. 2–4 STATE STUDENT REGISTRATION SYSTEM...............................................................................................2–4 System Design....................................................................................................................................2–4 LOCALLY ASSIGNED STUDENT IDENTIFIER ............................................................................................2–5 District Responsibility .......................................................................................................................2–5 SECTION 3 LEGAL ADVISORY .......................................................................................................................... 3–6 I. PURPOSES AND GOALS OF THE STUDENT INFORMATION -

Candidates for the U.S. Presidential Scholars Program January 2018

Candidates for the U.S. Presidential Scholars Program January 2018 [*] Candidate for Presidential Scholar in the Arts. [**] Candidate for Presidential Scholar in Career and Technical Education. [***]Candidate for Presidential Scholar and Presidential Scholar in the Arts [****]Candidate for Presidential Scholar and Presidential Scholar in Career and Technical Education Alabama AL - Ellie M. Adams, Selma - John T Morgan Academy AL - Kaylie M. Adcox, Riverside - Pell City High School AL - Tanuj Alapati, Huntsville - Randolph School AL - Will P. Anderson, Auburn - Auburn High School AL - Emma L. Arnold, Oxford - Donoho School The AL - Jiayin Bao, Madison - James Clemens High School AL - Jacqueline M. Barnes, Auburn - Auburn High School AL - Caroline M. Bonhaus, Tuscaloosa - Tuscaloosa Academy AL - William A. Brandyburg, Mobile - Saint Luke's Episcopal School: Upper School AL - Jordan C. Brown, Woodland - Woodland High School [**] AL - Cole Burns, Lineville - Lineville High School AL - Adelaide C. Burton, Mountain Brk - Mountain Brook High School [*] AL - Willem Butler, Huntsville - Virgil I. Grissom High School AL - Dylan E. Campbell, Mobile - McGill-Toolen Catholic High School AL - Sofia Carlos, Mobile - McGill-Toolen Catholic High School AL - Sara Carlton, Letohatchee - Fort Dale South Butler Academy [**] AL - Keenan A. Carter, Mobile - W. P. Davidson Senior High School AL - Amy E. Casey, Vestavia - Vestavia Hills High School AL - Madison T. Cash, Fairhope - Homeschool AL - Kimberly Y. Chieh, Mobile - Alabama School of Math & Science AL - Karenna Choi, Auburn - Auburn High School AL - Logan T. Cobb, Trussville - Hewitt-Trussville High School AL - Julia Coccaro, Spanish Fort - Spanish Fort High School AL - David M. Coleman, Owens Crossroad - Huntsville High School AL - Marvin C. Collins, Mobile - McGill-Toolen Catholic High School AL - Charlotte M. -

NEPSAC Constitution and By-Laws

NEW ENGLAND PREPARATORY SCHOOL ATHLETIC COUNCIL EXECUTIVE BOARD PRESIDENT MARK CONROY, WILLISTON NORTHAMPTON SCHOOL FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT: DAVID GODIN, SUFFIELD ACADEMY SECRETARY: RICHARD MUTHER, TABOR ACADEMY TREASURER: BRADLEY R. SMITH, BRIDGTON ACADEMY TOURNAMENT ADVISORS: KATHY NOBLE, LAWRENCE ACADEMY JAMES MCNALLY, RIVERS SCHOOL VICE-PRESIDENT IN CHARGE OF PUBLICATION: KATE TURNER, BREWSTER ACADEMY PAST PRESIDENTS RICK DELPRETE, HOTCHKISS SCHOOL NED GALLAGHER, CHOATE ROSEMARY HALL SCHOOL MIDDLE SCHOOL REPRESENTATIVES: MIKE HEALY, RECTORY SCHOOL MARK JACKSON, DEDHAM COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL DISTRICT REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT I BRADLEY R. SMITH, BRIDGTON ACADEMY DISTRICT II KEN HOLLINGSWORTH, TILTON SCHOOL DISTRICT III JOHN MACKAY, ST. GEORGE'S SCHOOL GEORGE TAHAN, BELMONT HILL SCHOOL DISTRICT IV TIZ MULLIGAN , WESTOVER SCHOOL BRETT TORREY, CHESHIRE ACADEMY 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Souders Award Recipients ................................................................ 3 Distinguished Service Award Winners ............................................... 5 Past Presidents ................................................................................. 6 NEPSAC Constitution and By-Laws .................................................. 7 NEPSAC Code of Ethics and Conduct ..............................................11 NEPSAC Policies ..............................................................................14 Tournament Advisor and Directors ....................................................21 Pegging Dates ...................................................................................22 -

Membership Listing – Fund Year 2020

MEMBERSHIP LISTING – FUND YEAR 2020 Academy at Charlemont Cambridge College, Inc. Academy Hill School Inc Cambridge-Ellis School Academy of Notre Dame at Tyngsboro, Inc. Cambridge Friends School Inc. Allen-Chase Foundation Cambridge Montessori School American Congregational Association The Cambridge School of Weston Applewild School, Inc. Cape Cod Academy, Inc. The Arthur J. Epstein Hillel School The Carroll Center for the Blind, Inc. Assoc of Independent Schools in New England, Inc. Carroll School Atrium School Chapel Hill - Chauncy Hall School Bancroft School Charles River School Bay Farm Montessori Academy The Chestnut Hill School Beaver Country Day School The Children's Museum of Boston Belmont Day School Clark School for Creative Learning Belmont Hill School, Inc. College of the Holy Cross Bement School Common School Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology Commonwealth School Berkshire Country Day School COMPASS Berkshire Waldorf School, Inc. Concord Antiquarian Society Boston College High School Covenant Christian Academy, Inc. Boston Lyric Opera Company Creative Education Inc dba Odyssey Day School Boston Symphony Orchestra Curry College Inc Boston Trinity Academy Cushing Academy Boston Youth Symphony Orchestras, Inc. Dana Hall School Bradford Christian Academy Inc Dean College Brimmer & May School Dedham Country Day School Brooks School Delphi Academy of Boston Brookwood School, Inc. Derby Academy Buckingham, Browne & Nichols School Dexter Southfield, Inc. Cambridge Center for Adult Education, Inc. Discovery Museums, Inc Eastern Nazarene College MEMBERSHIP LISTING – FUND YEAR 2020 Epiphany School Inc Kingsley Montessori School Falmouth Academy, Inc. Kovago Developmental Foundation, Inc. Family Cooperative Laboure College, Inc. Fay School Lander-Grinspoon Academy Fayerweather Street School Inc Landmark School, Inc. Fenn School Laurel School, Laurel Education Fessenden School Learning Project, Inc. -

ANDOVER, MASSACHUSETTS APRIL 5, 1985 S Talefrd to Replace, Cobb As Dean of Residence Next Fall .- By-JANET

VOLMECVI, NO. 19 -.- PHILLIPS ACADEMY ANDOVER, MASSACHUSETTS APRIL 5, 1985 S talefrd To Replace, Cobb as Dean of Residence Next Fall .- By-JANET. CHOI Houeunslor-heds the- Phillish1cinPoes _ ~~~ ~and JOHN NESBETT cdm icplnrrytm Cobb announced his resignation -eadmaster Donald. McNemar oraiestdthuin,and upe from the position of Dean of nouncethatohnathn Stabefordvises student clubs and-organizations,- Residence this past January, noting nounedhat ohntl~a Stblefrd, such as the Ryley Room. that "people will have a hard time English Instructor and former West sen oen lei h o,- sg Quad- --South Cluster Dean,- w"il "Mr. Stableford will have to tailor seeing' seo lsengte.o," sg replace David Cobb as Dean of the job to his own interests nid thte aentonel to" b's -, ~Residence next fall. energies," Cobb surmised. I don't resignation, Headmaster McNemar SIt~bleford, a former Phillips think that he [Mr. Stableford] can invited nominations for a new Deant. Aa~ student and Princeton have the same interests that I had in From the recommendations of the Unive~sity graduate, returned to An - starting -projects - as- Dean of faut'n fte tdn oy h dove,-' in 1976 as an English teacher R-sidence," he added. Cobb asserted -Headmaster formed a large pool and( house counselor. In 1979, he that he believes that Stableford. will-whchenrodtoagup f becamne West Quad South's Cluster focus the job-'more on the Cluster finalisis."It was my decision, but it' 'Dean, hotding the position until 1984., Deans and on residential life. "I do was done in consultation with Mr. He is presently on sabbatical leave in one thousand things," commented Cobb and others," stated McNemar. -

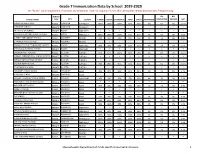

Grade 7 Immunization Data by School 2019-2020

Grade 7 Immunization Data by School 2019-2020 See "Notes" Tab for Explanation of Symbols and Limitations :*Did not respond; † Fewer than 30 students; ¶ Data discrepancies; ‡ Negative Gap SCHOOL UN- NO- SCHOOL NAME TYPE CITY COUNTY 2 MMR 3HEPB 2VARICELLA TDAP SERIES EXEMPTION IMMUNIZED RECORD GAP FROLIO MIDDLE SCHOOL PUBLIC ABINGTON PLYMOUTH 100% 100% 100% 82% 82% 0% 0% 0% 17.7% ST BRIDGET SCHOOL PRIVATE ABINGTON PLYMOUTH * * * * * * * * * JRI THE VICTOR SCHOOL PRIVATE ACTON MIDDLESEX † † † † † † † † † RAYMOND J GREY REG JR HIGH SCHOOL PUBLIC ACTON MIDDLESEX 100% 100% 100% 97% 96% 0% 0% 0% 3.6% ALBERT F FORD MIDDLE SCHOOL PUBLIC ACUSHNET BRISTOL 99% 99% 99% 99% 99% 1% 1% 0% 0.0% ST FRANCIS XAVIER SCHOOL PRIVATE ACUSHNET BRISTOL † † † † † † † † † BERKSHIRE ARTS & TECHNOLOGY CHARTER PUBLIC ADAMS BERKSHIRE 98% 98% 98% 92% 92% 6% 2% 0% 1.5% ST STANISLAUS KOSTKA SCHOOL PRIVATE ADAMS BERKSHIRE † † † † † † † † † GARDNER PILOT ACADEMY PUBLIC ALLSTON SUFFOLK 97% 97% 100% 82% 79% 0% 0% 0% 21.1% GERMAN INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL BOSTON PRIVATE ALLSTON SUFFOLK † † † † † † † † † HORACE MANN SCHOOL FOR DEAF PUBLIC ALLSTON SUFFOLK † † † † † † † † † JACKSON MANN SCHOOL PUBLIC ALLSTON SUFFOLK 98% 98% 95% 85% 83% 0% 0% 0% 17.1% ST HERMAN OF ALASKA PRIVATE ALLSTON SUFFOLK * * * * * * * * * AMESBURY MIDDLE SCHOOL PUBLIC AMESBURY ESSEX 99% 98% 98% 91% 91% 3% 1% 0% 5.7% SPARHAWK SCHOOL PRIVATE AMESBURY ESSEX * * * * * * * * * AMHERST REGIONAL MIDDLE SCHOOL PUBLIC AMHERST HAMPSHIRE 96% 94% 96% 95% 93% 4% 3% 0% 2.2% ANDOVER SCHOOL OF MONTESSORI PRIVATE ANDOVER ESSEX -

Brookwood School Manchester-By-The-Sea, Ma Head Of

BROOKWOOD SCHOOL MANCHESTER-BY-THE-SEA, MA HEAD OF SCHOOL START DATE: JULY 1, 2021 WWW.BROOKWOOD.EDU Mission Brookwood is a warm, child-centered community of exuberant learners with an extraordinary commitment to both the development of the mind and the development of the self. Through a purposeful balance of challenge, encouragement, and opportunity for appropriate risk-taking, the school fosters lifelong habits of inquiry, critical thinking, creativity and scholarship, just as it instills a healthy sense of self, a flexible mindset and a deep respect for the dignity of others. Ultimately, Brookwood strives to graduate academically accomplished individuals of conscience, character, compassion and cultural competence. OVERVIEW Brookwood School, founded in 1956, is an Early Childhood through Grade 8, coeducational, independent school located on a beautiful 30-acre campus in Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts, on the rocky coast north of Boston. Led by an exceptional faculty, the school offers a student-centered, academically engaging and varied program that nurtures and challenges students to reach their fullest potential. Brookwood understands that preparing students for the world in which we live today is a task entirely unlike that which educators faced even a decade ago. Along with the acquisition of knowledge, students need analytical and social-emotional skills in order to deconstruct the complexity of their lives and the evolving culture. To this end, the school supports learning in four dimensions: skill mastery and deep knowledge; kindness, caring, and empathy; leadership and change-making; and creativity. This balanced, personalized approach, along with the belief that a community is strongest when comprised of individuals with diverse backgrounds, experiences, and points of view, prepares students for success in high school and beyond. -

6Th Grade (131 Schools)

2011-2012 CONTEST SCORE REPORT SUMMARY FOR GRADES 6, 7, AND 8 Summary of Results 6th Grade Contests NEML Top 31 Schools in League--6th Grade (131 Schools) Rank School Town Team Score *1 Jonas Clarke Middle School Lexington, MA 168 *2 Diamond Middle School Lexington, MA 167 3 Mill Pond Intermediate Sch Westborough, MA 160 4 Sherwood Middle School Shrewsbury, MA 158 5 Eastern Middle School Riverside, CT 157 5 The Sage School Foxboro, MA 157 7 Wayland Middle School Wayland, MA 148 8 Park School Brookline, MA 147 9 Fenn School Concord, MA 146 10 Conant Elem. School Acton, MA 143 11 Freeman Centennial School Norfolk, MA 139 11 McCall Middle School Winchester, MA 139 11 Middle Sch of the Kennebunks Kennebunk, ME 139 11 Pike School Andover, MA 139 15 Winsor School Boston, MA 137 16 Squadron Line ES Simsbury, CT 136 16 Trottier Middle School Southborough, MA 136 18 Glenbrook Middle School Longmeadow, MA 134 18 Mary Hogan Elem. School Middlebury, VT 134 20 Middletown HS Middletown, CT 132 21 Londonderry Middle School Londonderry, NH 130 21 Morse Pond School Falmouth, MA 130 21 Wheeler School Providence, RI 130 24 Thompson Brook School Avon, CT 129 25 Foote School New Haven, CT 127 26 Ottoson Middle Sch Arlington, MA 125 26 Timothy Edwards Mid. Sch South Windsor, CT 125 28 Benton Elem. School Benton, ME 123 28 Maimonides Sch Brookline, MA 123 30 Hobomock Elementary School Pembroke, MA 122 30 Sage Park Middle School Windsor, CT 122 Top 34 Students in League--6th Grade Rank Student School Town Score *1 Jeremy C The Sage School Foxboro, MA 35 *1 Jonathan -

Celebrating Tomorrow’S Trailblazers Our Mission 3

2019 ANNUAL REPORT CHAMPIONING CHANGE CELEBRATING TOMORROW’S TRAILBLAZERS OUR MISSION 3 DEDICATION 4 OUR REACH 7 OUR MODEL 9 OUR MISSION 2019 MEMBER SCHOOLS 10 AFFILIATED COLLEGES 16 For nearly 60 years, A Better Chance has been working to OUR SUPPORTERS 18 make our mission a reality—to foster the leaders of color our STATEMENT OF ACTIVITIES 32 nation desperately needs. Through our incredible mission, the lives of 16,500 people of color have been forever TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE SUPPORT A BETTER CHANCE 36 transformed, empowering students to become forces of change and progress in our society. 3 DEDICATION Dear Alumni, Friends and Parents, Through the work of our talented staff, dedicated partners, and devoted National Board of Directors, 2019 was a strong year for A Better Chance. The progress we made created opportunities for nearly 500 talented students to reach their highest potential. For nearly 60 years, A Better Chance has been a preeminent force of change in our society. Through the incredible educational opportunities available through our program, the trajectory of over 16,500 lives has been altered. In 2019, 471 additional Scholars were placed at one of our 329 highly competitive Member Schools with $18.2 million in financial aid leveraged for their educations. Our devoted team made these placements possible while continuing to support the currently enrolled 2,206 Scholar community by providing summer enrichment opportunities, internships and leadership development workshops. We extend our thanks and appreciation to Sandra E. Timmons for her tireless leadership as President of the organization over the past sixteen years.