The Presidential Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donald J Trump: Nh Ững Điều C Ần Bi Ết Vĩnh T Ường

Th ời s ự Chính tr ị Mỹ Sưu t ầm - về Ông “Đô-la-Trâm” Donald J Trump: Nh ững Điều C ần Bi ết Vĩnh T ường Đúng v ậy! Có nhi ều ng ười b ảo r ằng tôi là th ường dân; tôi không c ần chính “ch ị” chính em gì c ả; tôi ch ỉ bầu cho b ất k ỳ ai trong đảng mà lâu nay tôi tin. Th ế có ngh ĩa là không c ần phán đoán, ch ọn lựa gì c ả vì đã có ng ười ch ọn s ẵn cho r ồi. Và b ầu c ử còn có ý ngh ĩa gì vì nó ch ẳng khác ở Vi ệt nam sau 1975 đến gi ờ! L ại có ng ười tin r ằng “th ường dân không làm chính tr ị”. Có đúng không n ếu nói r ằng ng ười dân không bao gi ờ ra kh ỏi xã h ội, không bao gi ờ ra kh ỏi sự chi phối sinh ho ạt hàng ngày trong khung c ảnh xã h ội d ưới th ể ch ế chính tr ị nh ất định mà họ đang s ống? N ếu câu tr ả lời là “Đúng” thì đã rõ m ỗi ng ười chúng ta không th ể không quan tâm đến v ấn đề chính tr ị, xã h ội chung quanh ta, tr ừ khi chúng ta t ừ bỏ hết nh ững gì thu ộc v ề chúng ta, đó chính là quy ền s ống an bình, th ịnh vượng và h ạnh phúc mà b ất k ỳ ai trong chúng ta c ũng đều hàng gi ờ đeo đuổi. -

Theory Talk #35 Barry Buzan on International Society, Securitization

Theory Talks Presents THEORY TALK #35 BARRY BUZAN ON INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY, SECURITIZATION, AND AN ENGLISH SCHOOL MAP OF THE WORLD Theory Talks is an interactive forum for discussion of debates in International Relations with an emphasis of the underlying theoretical issues. By frequently inviting cutting-edge specialists in the field to elucidate their work and to explain current developments both in IR theory and real-world politics, Theory Talks aims to offer both scholars and students a comprehensive view of the field and its most important protagonists. Citation: Schouten, P. (2009) ‘Theory Talk #35: Barry Buzan on International Society, Securitization, and an English School Map of the World’, Theory Talks, http://www.theory- talks.org/2009/12/theory-talk-35.html (19-12-2009) WWW.THEORY‐TALKS.ORG BARRY BUZAN ON INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY, SECURITIZATION, AND AN ENGLISH SCHOOL MAP OF THE WORLD Few thinkers have shown to be as capable as Barry Buzan of continuously impacting the direction of debates in IR theory. From regional security complexes to the English School approach to IR as being about international society, and from hegemony to securitization: Buzan’s name will appear on your reading list. It is therefore an honor for Theory Talks to present this comprehensive Talk with professor Buzan. In this Talk, Buzan – amongst others – discusses theory as thinking-tools, describes the contemporary regionalization of international society, and sketches an English School map of the world. What is, according to you, the biggest challenge / principal debate in current IR? What is your position or answer to this challenge / in this debate? I think the biggest challenge is a dual one, namely, to reconnect international relations with world history and sociology. -

All of the People, All of the Time: an Analysis of Public Reaction to the Use of Deception by Political Elites

All of the People, All of the Time: An Analysis of Public Reaction to the Use of Deception by Political Elites Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jakob A. Miller, B.A. Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Thomas Nelson, Advisor Michael Neblo Nathaniel Swigger Copyright by Jakob A. Miller 2017 Abstract Despite the public's uniformly dismal assessment of politicians' honesty, they react by punishing some offences and seemingly ignoring others. I use data from multiple survey experiments as well as an examination of electoral polling data to show that public reaction to accusations of deception against politicians is guided by the principle of expectancy violations. I find that when deception is expected, it does not draw cognitive focus from members of the public, thereby causing the public to punish only lies they find unusual. In this way, a reputation as a liar may produce a sort of inoculation effect: that is, the fact that a politician is often accused of lying may contribute to public tolerance of them continuing to do so. ii Dedication To my family, for their unfailing love and support. Bless you. iii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my committee. Thomas Nelson helped me to sort my ideas into an organized whole, and Michael Neblo and Nathaniel Swigger provided vital feedback and encouragement. I would also like to thank William Minozzi, who helped me get this project started in the first place. -

The Evolution of International Security Studies

THE EVOLUTION OF INTERNATIONAL SECURITY STUDIES BARRY BUZAN Department of International Relations London School of Economics and Political Science LENE HANSEN Department of Political Science University of Copenhagen 1568BB 12975 75 ,1297509D59B.19/B1BC2:5BBB85,12975,5 B56C51D191251B8BB 12975 75B5 8BB9 7 ,/ cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521694223 c Barry Buzan and Lene Hansen 2009 ⃝ This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2009 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge AcataloguerecordforthispublicationisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Buzan, Barry. The evolution of international security studies / Barry Buzan, Lene Hansen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-521-87261-4 1. Security, International – Study and teaching. 2. Security, International – Research. 3. Security, International – History. I. Hansen, Lene. II. Title. JZ5588.B887 2009 355′.033 – dc22 2009025609 ISBN 978-0-521-87261-4 hardback ISBN 978-0-521-69422-3 paperback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. 1568BB 12975 75 ,1297509D59B.19/B1BC2:5BBB85,12975,5 B56C51D191251B8BB 12975 75B5 8BB9 7 ,/ THE EVOLUTION OF INTERNATIONAL SECURITY STUDIES International Security Studies (ISS) has changed and diversified in many ways since 1945. -

Into Aspohyxiated

1! INTO ASPHYXIATED AIR Part 1: My Empathy Trek with The Trump Voter Vincent Greenwood, Ph.D., Executive Director “I hoped something would be gained by spilling my soul in the calamity’s immediate after- math, in the roil and torment of the moment… it hasn’t, of course.” -Jon Krakauer from Into Thin Air In 1996, 630 climbers attempted to reach the summit of Mt. Everest and 155 died. On May 10 of that year alone, 9 died, marking it as the deadliest day in the history of mountaineer- ing. On that day at 1pm, Jon Krakauer, a climber and journalist, stood on the summit, one foot in 2! China, one in Nepal. He had been hired by Outsider magazine to write a story about a growing trend: the development of commercial climbing expeditions, which many in the serious climbing community derisively termed the “monetization” of Everest. There is no question that the rivalry between such for-profit enterprises opened the door to amateurism, compromised safety procedures, and encouraged greed, hubris and poor judg- ment, borne of the need to deliver the goods (securing the summit) because the price was so steep: 65 grand back then, mostly ponied up by wealthy Western clients, some with scant climb- ing experience. On that ill-fated day, five such expeditions were zeroing in on the summit. Bot- tlenecks were created which exacerbated organizational and communication problems, certainly a key factor in the disaster that developed that day. Krakauer gazed at the vista below, the Tibetan Plateau, and beyond, where one can dis- cern the curvature of the Earth. -

Trump's New Face of Power in America

Trump’s New Face of Power in America (updated and revised June 2021) Bob Hanke1 York University, Toronto, Canada Abstract: This article proposes that the advent of Trumpism was an historical moment of danger that compels us to analyze the micropolitics of the present. In the first part, I describe the constellation that gave rise to Trumpism. In the second part, I recall Goffman’s concept of face-work and discuss how it remains relevant for describing Trump’s aggressive face-work. In the third part, I take Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of faciality as a point of departure for understanding micro- fascism. As an abstract machine, Trump’s faciality engendered and diffused fascisizing micropolitics around a messenger/disrupter in chief. It worked in connection with a landscape and relative to a collective assemblage of enunciation that extracted a territory of perception and affect. In the micropolitics of the present, the defining feature of Trumpism was how the corrupt abuse of power and the counterforces limiting his potency collided on an ominous, convulsive political reality TV show that threatened US democracy. Keywords: Trumpism, face-work, faciality, assemblage, micropolitics, impeachment, coronavirus pandemic We are all sufferers from history, but the paranoid is a double sufferer, since he is afflicted not only by the real world, with the rest of us, but by his fantasies as well. – Richard Hofstadter (1964) When a man unprincipled in private life desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper, possessed of considerable talents, -

Is Manipulation Within the Construct of Reality Television Ethical? Cheryl-Anne Whitlock University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2012 Is manipulation within the construct of reality television ethical? Cheryl-Anne Whitlock University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Whitlock, Cheryl-Anne, Is manipulation within the construct of reality television ethical?, Master of Arts - Research (Journalism) thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2012. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3967 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Is Manipulation within the Construct of Reality Television Ethical? A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts by Research (Journalism) from University of Wollongong by Cheryl-Anne Whitlock School of Creative Arts 2012 i Certification I, Cheryl-Anne Whitlock, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Master of Arts by Research (Journalism), in the Faculty of Law, Humanities and The Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Cheryl-Anne Whitlock 16 February 2012 ii Abstract The main purpose of the thesis is to determine to what extent duty of care is extended to reality television participants, to what extent elements of reality television programming are manipulated and whether those manipulations are ethical. Program participants are encouraged to be their ‘real’ and authentic selves, yet reality programming itself is often so extensively manipulated that the genre renders its own output inauthentic, thus compromising participants’ contributions and casting their performance in the same false light. -

An Analytical Survey of Critical Security Studies: Making the Case for a (Modified) Post-Structuralist Approach

An Analytical Survey of Critical Security Studies: Making the Case for a (Modified) Post-structuralist Approach Paper presented at the 2009 CPSA, Ottawa Jennifer Mustapha Department of Political Science McMaster University (DRAFT: Please do not cite without permission) Broadly stated, this essay is an analytical review of different approaches to theorizing security with an emphasis on the variety of approaches that can be loosely termed “critical.” 1 Importantly, I seek to highlight the relevance of ontological theorizations in debates about the meaning and definition of “security.” In doing so, I hope to call attention to the many nuances of the critical security studies literature and ultimately argue the benefits of employing a (modified) post-structuralist approach to understanding security. This “modification” is necessary because there is an inclination within some critical post-structuralist approaches to conflate epistemological commitments with ontological ones. This can be observed in what is arguably an unsustainable leap of reasoning, where acknowledgement of the indeterminacy of competing truth claims turns into an unwillingness to make any claims at all. In other words, the subject of security risks becoming invisible in the wake of continuous contestations about the dangers of essentialism and about the meaning of security itself. This is problematic on several fronts, such as in the context of critical approaches that make emancipatory declarations on behalf of the individual. The good news is that this is not necessarily the logical end-point of post-structuralist critiques, nor is it an indictment against the overall benefit of employing them. Furthermore, this analysis is not meant to detract from the core intention of a post-structuralist ethic, which seeks to interrogate and deconstruct the very meaning of security and the ways in which it is talked about. -

Digital Disaster, Cyber Security, and the Copenhagen School

International Studies Quarterly (2009) 53, 1155–1175 Digital Disaster, Cyber Security, and the Copenhagen School Lene Hansen University of Copenhagen and Helen Nissenbaum New York University This article is devoted to an analysis of cyber security, a concept that arrived on the post-Cold War agenda in response to a mixture of tech- nological innovations and changing geopolitical conditions. Adopting the framework of securitization theory, the article theorizes cyber secu- rity as a distinct sector with a particular constellation of threats and ref- erent objects. It is held that ‘‘network security’’ and ‘‘individual security’’ are significant referent objects, but that their political impor- tance arises from connections to the collective referent objects of ‘‘the state,’’ ‘‘society,’’ ‘‘the nation,’’ and ‘‘the economy.’’ These referent objects are articulated as threatened through three distinct forms of securitizations: hypersecuritization, everyday security practices, and tech- nifications. The applicability of the theoretical framework is then shown through a case-study of what has been labeled the first war in cyber space against Estonian public and commercial institutions in 2007. This article is devoted to an analysis of ‘‘cyber security,’’ a concept that arrived on the post-Cold War agenda in response to a mixture of technological innova- tions and changing geopolitical conditions. Cyber security was first used by com- puter scientists in the early 1990s to underline a series of insecurities related to networked computers, but it moved beyond a mere technical conception of com- puter security when proponents urged that threats arising from digital technolo- gies could have devastating societal effects (Nissenbaum 2005). Throughout the 1990s these warnings were increasingly validated by prominent American politi- cians, private corporations and the media who spoke about ‘‘electronic Pearl Harbors’’ and ‘‘weapons of mass disruption’’ thereby conjuring grave threats to the Western world (Bendrath 2003:50–3; Yould 2003:84–8; Nissenbaum 2005:67). -

The Magic of Donald Trump by Mark Danner | the New York Review of Books

5/11/2016 The Magic of Donald Trump by Mark Danner | The New York Review of Books The Magic of Donald Trump Mark Danner MAY 26, 2016 ISSUE Crippled America: How to Make America Great Again by Donald J. Trump Threshold, 193 pp., $25.00 Like Hercules, Donald Trump is a work of fiction.1 Primed for miracles and wonders, Trumpsters in their thousands tilt their heads up toward the blueblack Florida sky. Behind the approaching thwackthwackthwack the electronic fanfare soars and above it now we hear the booming carnival barker’s comeon: “Now arriving out of the northwest sky, DONALD…J… TRUMP!” Thousands of upturned mouths gape as the three floating lights, turning slowly, majestically resolve themselves into the shape of the big helicopter, the inevitable TRUMP in signature AkzidenzGrotesk font just visible on its tail. Six thousand roaring voices—or is it seven thousand, or eight, or nine?—crash in a wave of sound against the raucous electrobrass salute. The earsplitting blare is the theme to Air Force One, a cheesy late1990s hit starring Harrison Ford as MedalofHonorwinning President James Marshall, whose Boeing is seized by terrorists. (President Marshall growling to an abouttobedefenestrated terrorist: “Get off my plane!”) Can one imagine any other candidate using this as theme music? For Ted Cruz or John Kasich or any of the fourteen others who have wandered on and then off the stage, the irony—the lack of self Donald Trump; drawing by James Ferguson seriousness—would be unendurable. -

Never Has Trump Ever … 1

NEVER HAS TRUMP EVER … 1. Misspelled “unprecedented” as “unpresidented.” • ANSWER: GUILTY • SOURCE: “Donald Trump accuses China of ‘unpresidented’ act over US navy drone” (The Guardian) 2. Said he is a “self-made millionaire.” • ANSWER: NOT GUILTY • SOURCE: “Donald Trump describes father’s ‘small loan’: $1 million” (CNN) 3. Tweeted over 100 times in a day. • ANSWER: GUILTY • SOURCE: “Trump appears to set personal record for tweets in a day” (The Hill) 4. Written a Time Magazine tribute to Hillary Clinton. • ANSWER: NOT GUILTY (Senator Lindsey Graham wrote Hilary Clinton a Time Magazine tribute in 2006!) • SOURCE: Hilary Clinton on Lindsey Graham: ‘It’s like he had a brain snatch” (Politico) 5. Tweeted “READ THE TRANSCRIPTS.” • ANSWER: GUILTY • SOURCE: @realDonaldTrump’s tweet on January 21st, 2020 (Twitter) 6. Cyber-bullied a teen, environmental activist. • ANSWER: GUILTY • SOURCE: @realDonaldTrump’s tweet on December, 19th, 2020 (Twitter) 7. Tweeted Justice Kavanaugh should sue people for “liable” rather than “libel.” • ANSWER: GUILTY • SOURCE: “Trump stands up for Brett Kavanaugh over ‘liable’” (Politico) 8. Been the only president to not release their tax returns. • ANSWER: GUILTY • SOURCE: “Presidential tax returns: It started with Nixon. Will it end with Trump?” (CNN) 9. Started a sentence with “I’m not a doctor, but…” • ANSWER: GUILTY • SOURCE: “Trump promotes use of drug for coronavirus: ‘I’m not a doctor. But I have common sense’” (The Hill) 10. Said climate change is “fake news.” • ANSWER: GUILTY • SOURCE: “Trump tweets climate change skeptic in latest denial of science” (CNN) 11. Said global warming was created by the Chinese. • ANSWER: GUILTY • SOURCE: “Trump didn’t delete his tweet calling global warming a Chinese hoax” (The Washington Post) 12. -

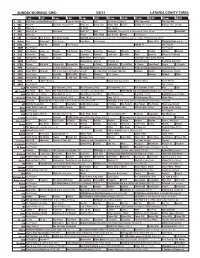

Sunday Morning Grid 5/6/12 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/6/12 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid The Players Club (N) AMA Supercross PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Babar (TVY) Willa’s Wild Pearlie Cycling Giro d’Italia. Hockey: Blues at Kings 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Chicago Bulls at Philadelphia 76ers. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Prince Mike Webb Joel Osteen Shook Paid Program 11 FOX D. Jeremiah Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: Aaron’s 499. From Talladega Superspeedway in Talladega, Ala. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Tomorrow’s Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Hates Chris Changing Lanes ››› 18 KSCI Paid Hope Hr. Church Paid Program Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Sara’s Kitchen Kitchen Mexican 28 KCET Hands On Raggs Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Land/Lost Hey Kids Taste Journeys Moyers & Company 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Paid Program Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tú Al Punto (N) Vidas Paralelas República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B.