DBCT Declaration Review - Response to Initial Submissions 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Company Annual Report 2011 a Disciplined Approach a Proven Strategy We Are BHP Billiton, a Leading Global Resources Company

For personal use only Our Company Annual Report 2011 A disciplined approach A proven strategy We are BHP Billiton, a leading global resources company. Our purpose is to create long-term shareholder value through the discovery, acquisition, development and marketing of natural resources. For personal use only BHP Billiton Limited. ABN 49 004 028 077. Registered in Australia. Registered office: 180 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia. BHP Billiton Plc. Registration number 3196209. Registered in England and Wales. Registered office: Neathouse Place, London SW1V 1BH, UK. Each of BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton Plc are members of the BHP Billiton Group, which is headquartered in Australia. Contents 1 Key information 3 4 Board of Directors and information Key 1 1.1 Our business 3 Group Management Committee 104 1.2 Chairman’s Review 4 4.1 Board of Directors 104 1.3 Chief Executive Offi cer’s Report 5 4.2 Group Management Committee 107 1.4 Selected key measures 6 5 Corporate Governance Statement 108 1.5 Risk factors 7 5.1 Governance at BHP Billiton 108 1.6 Forward looking statements 11 5.2 Shareholder engagement 109 2 Information on the Company 12 5.3 Board of Directors 109 2.1 BHP Billiton locations 12 5.4 Board of Directors – Review, Information on the Company 2 2.2 Business overview 14 re-election and renewal 115 2.2.1 History and development 14 5.5 Board Committees 117 2.2.2 Petroleum Customer Sector Group 14 5.6 Risk management 124 2.2.3 Aluminium Customer Sector Group 21 5.7 Management 125 2.2.4 Base Metals Customer -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

BHP Billiton Limited ABN 49 004 028 077 180 Lonsdale Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Australia 18 September 2012 Tel +61 1300 55 47 57 Fax +61 3 9609 3015 www.bhpbilliton.com To: Australian Securities Exchange 2012 US ANNUAL REPORT (Form 20-F) Please find attached a copy of BHP Billiton’s 2012 US Annual Report (Form 20-F), which has been filed with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission. This document has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the United States Securities and Exchange Commission and, as such, does not comply with the reporting requirements under the Australasian Code for Reporting of Exploration Results, Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves. Jane McAloon Group Company Secretary For personal use only A member of the BHP Billiton Group which is headquartered in Australia Registered Office: Level 27 BHP Billiton Centre, 180 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia ABN 49 004 028 077 Registered in Australia UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2012 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report For the transition period from to Commission file number: 001-09526 Commission file number: 001-31714 BHP BILLITON LIMITED BHP BILLITON PLC (ABN 49 004 028 077) (REG. -

![Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Wednesday, 23 November 2011] P9642b-9644A Hon Norman Moore [1] Receipt and First Reading Bill](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8480/extract-from-hansard-council-wednesday-23-november-2011-p9642b-9644a-hon-norman-moore-1-receipt-and-first-reading-bill-1098480.webp)

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Wednesday, 23 November 2011] P9642b-9644A Hon Norman Moore [1] Receipt and First Reading Bill

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Wednesday, 23 November 2011] p9642b-9644a Hon Norman Moore IRON ORE AGREEMENTS LEGISLATION (AMENDMENT, TERMINATION AND REPEALS) BILL 2011 Receipt and First Reading Bill received from the Assembly; and, on motion by Hon Norman Moore (Leader of the House), read a first time. Second Reading HON NORMAN MOORE (Mining and Pastoral — Leader of the House) [7.35 pm]: I move — That the bill be now read a second time. The purpose of this bill is to authorise variation agreements that amend five iron ore state agreements held by BHP Billiton and its joint venture partners; to ratify an agreement between the state and BHP Billiton and others that terminates the Iron Ore Beneficiation (BHP) Agreement 1996, which I will refer to as the termination agreement; and to repeal three related BHP iron ore processing acts. The following state agreements are to be varied: Iron Ore (Mount Newman) Agreement 1964, Iron Ore (Mount Goldsworthy Agreement) 1964, Iron Ore (Goldsworthy–Nimingarra) Agreement 1972, Iron Ore (McCamey’s Monster) Agreement 1972, and Iron Ore (Marillana Creek) Agreement 1991. The variation agreements provide for increased royalty rates for iron ore fines on a staged basis and other amendments to facilitate BHP Billiton’s Pilbara operations and expansion programs. The amendments to the state agreements noted above will introduce a phased increase in the royalty rate for fines ore from 5.625 per cent to 6.5 per cent from 1 July 2012; and from 6.5 per cent to 7.5 per cent from 1 July 2013 to match the lump ore rate. -

BHP Billiton Submission to the Productivity Commission’S Inquiry Into the National Access Regime 15 February 2013 1

BHP Billiton Submission to the Productivity Commission’s Inquiry into the National Access Regime 15 February 2013 1 Contents 1. THE OVERRIDING OBJECTIVE: CORRECT DECISIONS 2 2. BHP BILLITON'S EXPERIENCE OF THE PART IIIA DECLARATION PROCESS 4 2.1 FMG's applications for declaration of BHP Billiton's Pilbara iron ore railways 4 2.2 Key features of Part IIIA declaration decisions 4 2.3 The Part IIIA declaration process 5 3. PROPOSAL TO REDUCE THE TIME TAKEN TO RESOLVE PART IIIA APPLICATIONS 8 3.1 Introduction 8 3.2 Summary of recommendations 8 3.3 Proposal concerning associated procedural and administrative arrangements 10 3.4 Alternative proposals should be approached with significant caution 11 4. HOW SHOULD PART IIIA IDENTIFY CASES WHEN DECLARATION IS NOT APPROPRIATE? 12 4.1 Introduction 12 4.2 Summary of recommendations 12 4.3 Declaration criterion (a) – declaration should only be available where the competition benefits from access are substantial 13 4.4 Declaration criterion (b) – the private test best promotes the objects of Part IIIA 13 4.5 Declaration criterion (f) – retain the current public interest criterion, and introduce a new criterion to assess the costs economic and benefits of access 14 4.6 Introduce a new criterion, to assess whether the facility has or is likely to have capacity to provide the service 15 4.7 The "production process" exception – services which involve the use of a material part of a production process should be excluded from the definition of "service" 16 5. FURTHER OBSERVATIONS – STAGE TWO OF PART IIIA 16 ANNEXURE A EXAMPLES OF INFRASTRUCTURE SHARING IN BHP BILLITON'S BUSINESS ANNEXURE B PART IIIA DECLARATION: THE EXPERIENCE IN THE PILBARA RAIL PROCEEDINGS ANNEXURE C DECLARATION CRITERION (B) 2 A. -

Thatdeliver the Strategicdrivers

5041 BHPB AR06 cover_UK 13/9/06 10:35 PM Page 1 BHP Billiton Annual Report 2006 BHP Billiton Annual Report The Strategic Drivers that deliver the Essential Elements www.bhpbilliton.com Annual Report 2006 WorldReginfo - c6478d1e-7999-4617-a7c0-05343b86108a 5041 BHPB AR06 cover_UK 13/9/06 10:35 PM Page 2 Corporate Directory BHP BILLITON GROUP MARKETING OFFICES New Zealand We are BHP Billiton, a leading global resources REGISTERED OFFICES The Netherlands Computershare Investor Services Limited Level 2/159 Hurstmere Road company. BHP BILLITON LIMITED Verheeskade 25 2521 BE The Hague Takapuna North Shore City Australia Postal Address – Bag 92119 Auckland 1020 BHP Billiton Limited Telephone (31 70) 315 6666 Telephone (64 9) 488 8777 Our purpose is to create long-term value through the BHP Billiton Centre Facsimile (31 70) 315 6767 Facsimile (64 9) 488 8787 discovery, development and conversion of natural 180 Lonsdale Street Singapore Melbourne VIC 3000 168 Robinson Road #10-01 United States resources, and the provision of innovative customer Telephone (61 3) 9609 3333 Capital Tower Computershare Investor Services Facsimile (61 3) 9609 3015 Singapore 068912 2 North LaSalle Street and market-focused solutions. Telephone (65) 6349 3333 Chicago, IL 60602 BHP BILLITON PLC Facsimile (65) 6349 4000 Postal Address – PO Box 0289 United Kingdom Chicago, IL 60690-9569 Our seven strategic drivers assist us in achieving our Neathouse Place Telephone 1 888 404 6340 objectives. These drivers are our people; our licence to London SW1V 1BH SHARE REGISTRARS AND (toll-free within US) Telephone (44 20) 7802 4000 TRANSFER OFFICES Facsimile (1 312) 461 4331 operate; our world-class assets; the way we do business; Facsimile (44 20) 7802 4111 Australia ADR Depositary, Transfer Agent and Registrar our financial strength and discipline; our project pipeline; Company Secretaries BHP Billiton Limited Registrar JPMorgan Chase Bank, NA Computershare Investor Services JPMorgan Service Center Karen J Wood (Group Company Secretary) Pty Limited PO Box 3408 and growth options. -

Introducing Competition Into Natural Monopoly Industries

Introducing Competition into Natural Monopoly Industries: An Evaluation of Mandated Access to Australian Freight Railroads By Mark Fagan, Senior Fellow* Taubman Center for State and Local Government WP-2008-01 1 I. Study Context Policy makers have long grappled with introducing competition into natural monopoly industries such as transportation, telecommunications and electricity in order to eliminate excess profits and assure efficient provision of service. Freight railroads presented a particular challenge because rather than earn monopoly rents, the industry in North America, Europe and Australia struggled to remain financially viable in the face of competition from other modes, especially trucks. For example, US rail share of freight transportation declined 33% between 1950 and 1975. During the 1970s, the rail industry’s return on equity was in the 3% range and return on sales was only 4%. Several major US railroads declared bankruptcy in the 1970s including the Penn Central, the Rock Island, and the Erie Lackawanna. The freight rail experience in Europe and Australia was similar although government subsidies and road freight regulation kept the railroads in business. Policy makers in the US were the first to tackle the problem of freight railroad viability. The solution adopted was total economic deregulation. The rationale for the change was that regulation was inhibiting the rail industry from responding to competitive pressures from the trucking industry. With the Staggers Act of 1980, US railroads were free to enter and exit markets, introduce new service offerings, enter into private contracts with shippers, set rates and abandon track. Over the next two decades, the railroads reduced costs, rationalized capacity and increased productivity. -

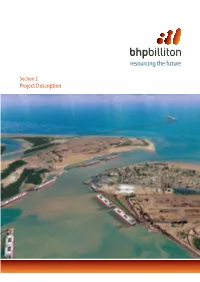

Section 2 Project Description

2. Project Description 2. Project Section 2 Project Description Section 2 | Project Description 2 Project Description Key marine structures include: ▸ an abutment (on Finucane Island), jetty and This chapter describes the offshore and onshore wharf; components of the proposed Outer Harbour ▸ mooring and associated mooring dolphins; Development in Port Hedland. It provides a brief ▸ associated transfer stations, ore conveyors description of construction methodology, operations and shiploaders; and decommissioning, and provides the basis for the environmental impact assessment, and ▸ berth pockets, basins and channels; and determination of the potential environmental and ▸ aids to navigation. social impacts. This project description is based on the engineering investigation and design completed to date and 2.1 The Project incorporates alternatives and options which are still The proposed Outer Harbour Development will being considered. Alternatives will be evaluated as involve the construction and operation of landside BHP Billiton Iron Ore continues with the detailed and marine infrastructure for the handling and export engineering and design process prior to construction. of iron ore from BHP Billiton’s Iron Ore operations. Alternatives that have been discounted are discussed This section describes the landside and marine in Section 3. components, as well as the supporting infrastructure BHP Billiton Iron Ore’s investment in the development and ore handling operations. An overview of the of the Outer Harbour proposal remains subject to project’s location and layout is shown in Figure 1.2. external factors which are outside of its control, The key characteristics of the project are outlined in such as market conditions. Investment decisions will Table 2.1. -

Goldsworthy Railway

Goldsworthy Railway Application for declaration of a service provided by the Goldsworthy Railway under section 44F(1) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 Final Recommendation 29 August 2008 Table of Contents Abbreviations and glossary of terms ............................................................................... 7 1 Council processes and final recommendation ............................................................. 13 Final recommendation ............................................................................................................ 15 2 The application .......................................................................................................... 16 The application and applicant................................................................................................. 16 The service sought to be declared .......................................................................................... 16 The facility ............................................................................................................................... 17 The service provider ............................................................................................................... 18 The decision maker ................................................................................................................. 18 Other Pilbara railway applications .......................................................................................... 19 Issues regarding the application ............................................................................................ -

Our Company Annual Report 2011 a Disciplined Approach a Proven Strategy We Are BHP Billiton, a Leading Global Resources Company

Our Company Annual Report 2011 A disciplined approach A proven strategy We are BHP Billiton, a leading global resources company. Our purpose is to create long-term shareholder value through the discovery, acquisition, development and marketing of natural resources. BHP Billiton Limited. ABN 49 004 028 077. Registered in Australia. Registered office: 180 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia. BHP Billiton Plc. Registration number 3196209. Registered in England and Wales. Registered office: Neathouse Place, London SW1V 1BH, UK. Each of BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton Plc are members of the BHP Billiton Group, which is headquartered in Australia. Contents 1 Key information 3 4 Board of Directors and information Key 1 1.1 Our business 3 Group Management Committee 104 1.2 Chairman’s Review 4 4.1 Board of Directors 104 1.3 Chief Executive Offi cer’s Report 5 4.2 Group Management Committee 107 1.4 Selected key measures 6 5 Corporate Governance Statement 108 1.5 Risk factors 7 5.1 Governance at BHP Billiton 108 1.6 Forward looking statements 11 5.2 Shareholder engagement 109 2 Information on the Company 12 5.3 Board of Directors 109 2.1 BHP Billiton locations 12 5.4 Board of Directors – Review, Information on the Company 2 2.2 Business overview 14 re-election and renewal 115 2.2.1 History and development 14 5.5 Board Committees 117 2.2.2 Petroleum Customer Sector Group 14 5.6 Risk management 124 2.2.3 Aluminium Customer Sector Group 21 5.7 Management 125 2.2.4 Base Metals Customer Sector Group 23 5.8 Diversity at BHP Billiton -

BASIC DATA Goldsworthy Railway

PILBARA IRON ORE MINING CONTRIBUTORS TO THE RAILWAYS In the early 1960s the Commonwealth Government ended an embargo on The development of the original heavy haul railways and their subsequent the export of iron ore, stimulating mining development in the Pilbara region upgrading and expansion is a credit to the many engineers, scientists, and the start of a major export industry that has been of great economic technicians, tradesmen, labourers and others who contributed to the work. importance to Australia. These came from the mining companies, contractors, consultants, manufacturers, universities and government agencies involved. This was the first large scale industrial development in the region and has been the catalyst for the development of new towns and ports, leading to A significant role in the original construction was played by workers from large increases in population and local economic activity. Thursday Island and other Torres Strait islands who were highly skilled and productive tracklayers. In May 1968, workers on the Mt Newman railway project, many of whom were islanders, broke the world tracklaying HEAVY HAUL RAILWAYS record. In one day they laid, anchored and spiked 4.35 miles (about 7km) The heavy haul railways are an essential part of the development of iron First train to leave Tom Price, 1966 of track, breaking the previous US record of 2.88 miles (4.6km). ore production in the Pilbara. The four original railways connected four mines to ports at Port Hedland, Dampier and Cape Lambert. They were the first standard gauge, heavy haul railways in Australia, and the first ex- HAMERSLEY AND ROBE RIVER HEAVY HAUL RAILWAYS tensive privately owned and operated railways. -

Concise Annual Report 2008

Concise Annual Report 2008 For several years now, Asian economies have been driven by a fundamental shift in the rate of industrialisation and urbanisation of their massive populations. These economies have accounted for more global growth than has the United States. This growth will drive the course of the world economy for years to come. BHP Billiton produces and supplies world markets, including the developing Asian and other economies, with many of the natural resources they rely on to fuel their growth. These resources include iron ore, copper, nickel, alumina, manganese, coal, uranium, oil and gas. As the world’s leading natural resources company, we are central to the growth of the world’s developing economies. We really are resourcing the future. CONTENTS 1. Key Information 4. Board of Directors and Group Group Highlights 2008 2 Management Committee 26 Five-year Summary 2 5. Corporate Governance Statement 31 Chairman’s Review 4 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 6 6. Remuneration Report 44 2. Information on the Company 7. Directors’ Report 56 BHP Billiton Locations 8 8. Legal proceedings 68 Customer Sector Group Performance 10 9. Summary Financial Report 71 3. Operating and financial review and prospects 10. Glossary 85 Resourcing the Future 16 11. Shareholder Information 88 World-class Assets 18 Our People 20 Corporate Directory IBC Sharing Value 22 Growth 24 This Concise Annual Report is issued subject to the Important Notices appearing on the inside back cover of this Concise Annual Report. BHP Billiton is a Dual Listed Company comprising BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton Plc. The two entities continue to exist as separate companies but operate as a combined group known as BHP Billiton. -

What We Value Annual Report 2012 Our Charter

What we value Annual Report 2012 Our Charter We are BHP Billiton, a leading global resources company. Our purpose is to create long-term shareholder value through the discovery, acquisition, development and marketing of natural resources. Our strategy is to own and operate large, long-life, low-cost, expandable, upstream assets diversified by commodity, geography and market. Our Values Sustainability Putting health and safety first, being environmentally responsible and supporting our communities. Integrity Doing what is right and doing what we say we will do. Respect Embracing openness, trust, teamwork, diversity and relationships that are mutually beneficial. Performance Achieving superior business results by stretching our capabilities. Simplicity Focusing our efforts on the things that matter most. Accountability Defining and accepting responsibility and delivering on our commitments. We are successful when: Our people start each day with a sense of purpose and end the day with a sense of accomplishment. Our communities, customers and suppliers value their relationships with us. Our asset portfolio is world-class and sustainably developed. Our operational discipline and financial strength enables our future growth. Our shareholders receive a superior return on their investment. Marius Kloppers Chief Executive Officer September 2011 BHP Billiton Limited. ABN 49 004 028 077. Registered in Australia. Registered office: 180 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia. BHP Billiton Plc. Registration number 3196209. Registered in