The Disappearance of the Neighborhood Assembly Movement in Buenos Aires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guia Del Participante

“STRENGTHENING THE TUBERCULOSIS LABORATORY NETWORK IN THE AMERICAS REGION” PROGRAM PARTICIPANT GUIDELINE The Andean Health Organization - Hipolito Unanue Agreement within the framework of the Program “Strengthening the Network of Tuberculosis Laboratories in the Region of the Americas”, gives you the warmest welcome to Buenos Aires - Argentina, wishing you a pleasant stay. Below, we provide information about the city and logistics of the meetings: III REGIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING OF TUBERCULOSIS LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNANCE WORKSHOP II FOLLOW-UP MEETING Countries of South America and Cuba Buenos Aires, Argentina September 4 and 5, 2019 VENUE Lounge Hidalgo of El Conquistador Hotel. Direction: Suipacha 948 (C1008AAT) – Buenos Aires – Argentina Phones: + (54-11) 4328-3012 Web: www.elconquistador.com.ar/ LODGING Single rooms have been reserved at The Conquistador Hotel Each room has a private bathroom, heating, WiFi, 32” LCD TV with cable system, clock radio, hairdryer. The room costs will be paid directly by the ORAS - CONHU / TB Program - FM. IMPORTANT: The participant must present when registering at the Hotel, their Passport duly sealed their entry to Argentina. TRANSPORTATION Participants are advised to use accredited taxis at the airport for their transfer to The Conquistador hotel, and vice versa. The ORAS / CONHU TB - FM Program will accredit in its per diems a fixed additional value for the concept of mobility (airport - hotel - airport). Guideline Participant Page 1 “STRENGTHENING THE TUBERCULOSIS LABORATORY NETWORK IN THE AMERICAS REGION” PROGRAM TICKETS AND PER DIEM The TB - FM Program will provide airfare and accommodation, which will be sent via email from our office. The per diem assigned for their participation are Ad Hoc and will be delivered on the first day of the meeting, along with a fixed cost for the airport - hotel - airport mobility. -

Listado De Farmacias

LISTADO DE FARMACIAS FARMACIA PROVINCIA LOCALIDAD DIRECCIÓN TELÉFONO GRAN FARMACIA GALLO AV. CORDOBA 3199 CAPITAL FEDERAL ALMAGRO 4961-4917/4962-5949 DEL MERCADO SPINETTO PICHINCHA 211 CAPITAL FEDERAL BALVANERA 4954-3517 FARMAR I AV. CALLAO 321 CAPITAL FEDERAL BALVANERA 4371-2421 / 4371-4015 RIVADAVIA 2463 AV. RIVADAVIA 2463 CAPITAL FEDERAL BALVANERA 4951-4479/4953-4504 SALUS AV. CORRIENTES 1880 CAPITAL FEDERAL BALVANERA 4371-5405 MANCINI AV. MONTES DE OCA 1229 CAPITAL FEDERAL BARRACAS 4301-1449/4302-5255/5207 DANESA AV. CABILDO 2171 CAPITAL FEDERAL BELGRANO 4787-3100 DANESA SUC. BELGRANO AV.CONGRESO 2486 CAPITAL FEDERAL BELGRANO 4787-3100 FARMAPLUS 24 JURAMENTO 2741 CAPITAL FEDERAL BELGRANO 4782-1679 FARMAPLUS 5 AV. CABILDO 1566 CAPITAL FEDERAL BELGRANO 4783-3941 TKL GALESA AV. CABILDO 1631 CAPITAL FEDERAL BELGRANO 4783-5210 NUEVA SOPER AV. BOEDO 783 CAPITAL FEDERAL BOEDO 4931-1675 SUIZA SAN JUAN AV. BOEDO 937 CAPITAL FEDERAL BOEDO 4931-1458 ACOYTE ACOYTE 435 CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4904-0114 FARMAPLUS 18 AV. RIVADAVIA 5014 CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4901-0970/2319/2281 FARMAPLUS 19 AV. JOSE MARIA MORENO CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4901-5016/2080 4904-0667 99 FARMAPLUS 7 AV. RIVADAVIA 4718 CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4902-9144/4902-8228 OPENFARMA CONTEMPO AV. RIVADAVIA 5444 CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4431-4493/4433-1325 TKL NUEVA GONZALEZ AV. RIVADAVIA 5415 CAPITAL FEDERAL CABALLITO 4902-3333 FARMAPLUS 25 25 DE MAYO 222 CAPITAL FEDERAL CENTRO 5275-7000/2094 FARMAPLUS 6 AV. DE MAYO 675 CAPITAL FEDERAL CENTRO 4342-5144/4342-5145 ORIEN SUC. DAFLO AV. DE MAYO 839 CAPITAL FEDERAL CENTRO 4342-5955/5992/5965 SOY ZEUS AV. -

Embrace Buenos Aires

Embrace Buenos Aires The Hummingbird Trip - Private Concierge + Hospitality Consulting I Uriarte 1942 (1414) Buenos Aires, Argentina I +54911 3227 1111 I www.thehummingbirdtrip.com Embrace Buenos Aires David and Tonya’s Custom BA Itinerary Hi David and Tonya! Following please check out the itinerary crafted for you. I’ve design it centering the experience based on the professional photographers that you are and the kind of Art you are interested in. Your itinerary is thought to appreciate Buenos Aires through a lens, combining your passions, photography, art, food, with aesthetics that reflects our local identity, also considering David’s been here before and Tonya hasn’t.. Day 1 - December 29th Noon – Arrival in BA I will greet you at the Jorge Newbery Airport’s Private Terminal and a private transfer will drive you to the Four Seasons Hotel in Buenos Aires. Lunch Time - Osaka We’ll have a delighting lunch at Osaka, a Peruvian – Japanese Restaurant, one of the best ones in the city. 3pm - Graffiti Tour It is considered as Street Art, graffiti and all ways of art interventions taken place in the streets of a city. Nowadays it is contemplated as a way of Contemporary Art and it is becoming very popular in every city around the world. Buenos Aires streets are filled with colorful urban art from great local and international artists who find this city a heaven to work on. Around 3pm we’ll meet with our graffiti guide for a Private Tour to explore the neighborhoods of Colegiales, Palermo Hollywood and Soho, observing walls, visiting galleries and shops, getting to know the vibrant street art scene in Buenos Aires. -

Selected Investment Opportunities January 2018

SELECTED INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES JANUARY 2018 2. DISCLAIMER This booklet has been created by the Agencia Argentina de Inversiones y Comercio Internacional (“AAICI”) and is only intended to provide readers with basic information concerning issues of general interest and solely as a basis for preliminary discussions for the investment opportunities mentioned herein. Therefore, it does not constitute advice of any kind whatsoever. The figures contained in this presentation are for information purposes only and reflect prevailing economic, monetary, market, or other conditions as of January 2018. As consequence, this file and its contents shall not be deemed as an official or audited report or an invitation to invest or do business in Argentina nor shall it be taken as a basis for investment decisions. In preparing this document, project owners and their advisors have relied upon and assumed the accuracy and completeness of all available information. Therefore, neither the Agencia Argentina de Inversiones y Comercio Internacional nor the project owners or their advisors or any of their representa- tives shall incur any liability as to the accuracy, relevance or completeness of the information contained herein or in connection with the use of this file or the figures included therein. CONTENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INFRASTRUCTURE 10 POWER & RENEWABLE ENERGY 28 MINING 38 OIL & GAS 42 REAL ESTATE AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT 50 TELECOMMUNICATIONS & HIGH TECHNOLOGY 62 AGRIBUSINESS 68 .5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Agency has identified investment opportunities -

Los Diversos Mercados De Abastecimiento, Una Forma Diferente De Conocer La Ciudad De Buenos Aires ”

Trabajo Final de Práctica Profesional de la Licenciatura en Turismo “Los diversos Mercados de abastecimiento, una forma diferente de conocer la Ciudad de Buenos Aires ” Carrera: Licenciatura en Turismo Alumno: Brian Daglio Tutor: Prof: Fernando Navarro. 2020 1 INDICE INTRODUCCION. CAPITULO 1: EL OBJETO DE LA INVESTIGACIÓN. 1. Objetivos. 1.1 Objetivos Generales. 1.2 Objetivos Específicos. 2. Hipótesis de la Investigación. 3. Metodología de la Investigación. CAPITULO 2: EL TURISMO: DEFINICIONES, ESTRUCTURAS Y REGULACIONES. 2.1 Turismo Gastronómico 2.2 El Sistema Turístico 2.3 El Producto Turístico 2.4 Las Ciudades CAPITULO 3: TURISMO EN LA CIUDAD DE BUENOS AIRES. CAPITULO 4: LOS PRIMITIVOS Y AÚN CONSERVADOS MERCADOS DE ABASTECIMIENTO 4.1 El corazón de la ciudad 4.2 Hacia el norte de la catedral 4.3 De afuera hacia adentro 4.4 Hacia el sur 4.5 Radiografía urbana 4.6 Abastecimiento 4.7 Usos y costumbres 4.8 Colectividades 2 CAPITULO 5: PATIOS GASTRONÓMICOS, MERCADOS CONTEMPORANEOS, Y FERIA DE LAS COLECTIVIDADES. 5.1 Patios Gastronómicos 5.2 Mercados Contemporáneos 5.3 Próximos Mercados 5.4 Ferias de las Colectividades CAPITULO 6: PROPUESTA CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAFIAS ANEXOS 3 RESUMEN A lo largo de este trabajo estamos conociendo aspectos turísticos generales útiles para entender el desarrollo del turismo en CABA y la motivación de los visitantes. Como atractivo turístico de la ciudad, los mercados de productos son poco difundidos. Abordamos la historia, crecimiento y desarrollo hasta la actualidad de los Mercados de Productos. Durante sus comienzos se comercializaba en plazas y el traslado de productos ocurría en carretas y caballos. -

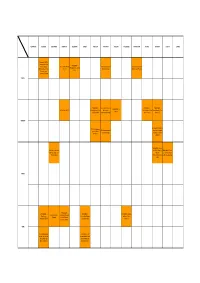

Calendario Version Pdf Separado

AGRONOMÍA ALMAGRO BALVANERA BARRACAS BELGRANO BOEDO CABALLITO CHACARITA COGHLAN COLEGIALES CONSTITUCIÓN FLORES FLORESTA LA BOCA LINIERS Semana del 7al 15 - Conmemoración de la Fecha Móvil - Semana Trágica. 8-Culto al Gauchito Gil 8- Culto al Gauchito Gil 8- Culto al Gauchito Gil Año Nuevo Chino (Barrio Marcha desde A.Troilo y (Villa 21) (Plaza Los Andes) (Bailanta Radio Estudio) Chino) Corrientes hasta Corrientes y Dorrego) ENERO Fecha Móvil - 5-Culto a Gardel- retorno Fecha Móvil - Fecha Móvil - 1- Día del barrio de 3- San Blas (Villa 21) Corso Autónomo (Plaza de los restos Corso Autónomo (Plaza Corso Autónomo (Plaza Coghlan 24 de Septiembre) (Cementerio Chacarita) de los Virreyes) Aramburu) FEBRERO 2- Nuestra Señora de la 15- Día del Barrio de 25- Conmemoración de Candelaria (Parroquia Caballito (Parque la muerte de Pappo Nuestra Señora de la Rivadavia) Candelaria) Fecha Móvil - Marcha 24- Marcha y acto 24 de al CCDyT “Olimpo” y Fecha Móvil - Marcha marzo (de Congreso a “Orletti”. en conmemoración de Plaza de Mayo) Conmemoración 24 de vecinos desaparecidos. marzo MARZO Fecha Móvil - Fecha Móvil - Fecha Móvil - Fecha Móvil - Verbena 1- Día del barrio de Vía Crucis (Parroquia Pesaj (Centro Feria de Abril (Rincón de Otoño (Centro Balvanera Nuestra Señora de Comunitario TZAVTA) Familiar Andaluz) Montañés) Caacupé - Villa 21) ABRIL 2- Aniversario de San 2- Aniversario de San Lorenzo (marcha desde Lorenzo (marcha desde Mexico 4000 hasta Mexico 4000 hasta Nuevo Gasómetro) Nuevo Gasómetro) PARQUE RESERVA MATADEROS MONSERRAT MONTE CASTRO NUEVA POMPEYA NUÑEZ PALERMO PARQUE CHACABUCO PARQUE PATRICIOS PATERNAL PUERTO MADERO RECOLETA RETIRO SAAVEDRA SAN CRISTÓBAL AVELLANEDA ECOLÓGICA Fecha Móvil (semana del 7 al 15) - Conmemoración 25 ° y Última Marcha de Semana Trágica 6- Día de Reyes 24- Feria de Alasitas la Resistencia (Plaza de (marcha desde Pepirí y (Zoológico y Shopping) (Parque Avellaneda) Mayo) A. -

Buenos Aires – May 2013

BUENOS AIRES – MAY 2013 ENG 294 – Capital of Culture Day 1 – Arrival and Coffee We arrive in the morning and walk to the obelisk (r), then go for coffee and media lunas at Café Tortoni – always rated one of the 10 Most Beautiful Cafes in the World – and also manage to find the park where the characters in The Tunnel would often meet. Friday, May 17 May Friday, On Cover (l-r) – Kenny Gilliard, Ashleigh Huffman, Daniel Faulkenberry and Juliane Bullard stand in Plaza Francia with the National Museum of Fine Arts behind them. This was a short walk from the hotel and just across the street from the flea market. EL ATENEO GRAN SPLENDID Day 2 – Exploring the City of Books Day 2 – La Biela and El Ateneo This coffee shop across the green from Saturday, May 18 May Saturday, Recoleta Cemetery is one of the most famous in the city, frequented by celebrities, past and present. Previous page: (l-r) Ashleigh Huffman, Kenny Gilliard, Daniel Faulkenberry and Juliane Bullard walk across the bridge over Avenida Libertador, linking the Recoleta Cemetery area to the law school and the park holding the steel flower, Floralis Generica, which supposedly opens at dawn and closes at dusk – although no one’s actually seen it in action. La Biela – The “Tie Rod” This is a great spot for breakfast or just hanging out for a coffee. You can even sit and have your picture taken with authors Jorge Luis Borges and Bioy Casares. Note the cutout on the chair – it’s a tie rod, a reference to the café’s early days. -

Oasiscollections Exclusive PERKS

Welcome to Buenos Aires, one of the most interesting and exciting cities in Latin America. Oasis Collections was founded in BA in 2009 and thus holds a special place among all of our destinations. Our BA-based team is made up of a combination of locals and ex-pats from around the world, all of whom love this city and pride themselves on knowing it inside out. Our tastes run the gamut from the hip and edgy to the more traditional, and we’ve created a guide which offers a broad range of suggestions covering gastronomy, nightlife and culture, while narrowing the selection down to what we consider the best in the city. Whether this is your first time in town or not, we hope you’ll find this guide helpful in making the most of your stay, and welcome any feedback on our recommendations or spots that you love that didn’t make our list. Share your travel experience: #oasiscollections EXCLUsive PERKS During your stay, enjoy access to the following perks. Simply show your Oasis keychain to get involved (unless otherwise noted). EL MERCADO DEL VINO PARAJE AREVALO 20% OFF BOTTLES OF WINE COMPLIMENTARY AFTER-MEAL GIFT Gorriti 4966, Palermo Soho Arévalo 1502, Palermo Hollywood Cozy wine shop in Palermo Soho. Oddly enough, they A small and comfy restaurant in the heart of Palermo also sell wooden furniture and have a sleek bar where Hollywood, surrounded by Colonial-style houses and you can enjoy some the best wines in Argentina. a bustling flea market. With a calm and nostalgic How to Redeem: Present Oasis Mobile App or Oasis atmosphere, Paraje Arevalo delivers with a simple Keychain dinner course that comes with a starter, main course Tel: +54 4833-4343 and dessert. -

Dinámica Del Mercado De Venta De Departamentos. Ciudad De Buenos Aires

Dinámica del mercado de venta de departamentos. Ciudad de Buenos Aires. 4to. trimestre de 2020 Informe de resultados 1538 Marzo de 2021 Resumen ejecutivo En el cuarto trimestre de 2020 se registró un descenso en el precio del m2 de departamentos en venta en los seis segmentos estudiados, con mayor fuerza en las unidades de 1 ambiente. La dinámica conjunta en el valor del m2 arrojó una retracción promedio del 6,8%, profundizando la baja iniciada en 2019 y consolidada para todos los segmentos desde el primer trimestre de 2020. El precio del m2 para los departamentos de 1 ambiente a estrenar fue de USD 2.905, valor que se redujo un 8,1% respecto del mismo período de 2019; mientras que las unidades usadas alcanzaron un precio del m2 de USD 2.714 con una caída del 8,5%, la más importante del trimestre. Los departamentos de 2 ambientes arrojaron un valor del m2 de USD 3.004 a estrenar y USD 2.593 los usados, ambos con descensos de precio (-7,2% en el primer caso y -5,7%, en el segundo). A su vez, el precio promedio del m2 de las unidades de 3 ambientes se ubicó en USD 3.071 para el conjunto a estrenar y USD 2.503 para el usado; en cuanto a la trayectoria interanual, las correspondientes variaciones se ubicaron en -6,3% y -5,3%, respectivamente. El contexto de descenso generalizado de precios se completa con una recuperación del stock de publicaciones respecto del trimestre anterior acercándose al volumen de departamentos disponibles en el último registro previo al inicio de la pandemia. -

Destination Report

Miami , Flori daBuenos Aires, Argentina Overview Introduction Buenos Aires, Argentina, is a wonderful combination of sleek skyscrapers and past grandeur, a collision of the ultrachic and tumbledown. Still, there has always been an undercurrent of melancholy in B.A. (as it is affectionately known by expats who call Buenos Aires home), which may help explain residents' devotion to that bittersweet expression of popular culture in Argentina, the tango. Still performed—albeit much less frequently now—in the streets and cafes, the tango has a romantic and nostalgic nature that is emblematic of Buenos Aires itself. Travel to Buenos Aires is popular, especially with stops in the neighborhoods of San Telmo, Palermo— and each of its colorful smaller divisions—and the array of plazas that help make up Buenos Aires tours. Highlights Sights—Inspect the art-nouveau and art-deco architecture along Avenida de Mayo; see the "glorious dead" in the Cementerio de la Recoleta and the gorgeously chic at bars and cafes in the same neighborhood; shop for antiques and see the tango dancers at Plaza Dorrego and the San Telmo Street Fair on Sunday; tour the old port district of La Boca and the colorful houses along its Caminito street; cheer at a soccer match between hometown rivals Boca Juniors and River Plate (for the very adventurous only). Museums—Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA: Coleccion Costantini); Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes; Museo Municipal de Arte Hispano-Americano Isaac Fernandez Blanco; Museo Historico Nacional; Museo de la Pasion Boquense (Boca football); one of two tango museums: Museo Casa Carlos Gardel or Museo Mundial del Tango. -

Agencias Turfito

AGENCIAS TURFITO Localidad Domicilio Altura AGRONOMIA AVENIDA SALVADOR MARIA DEL CARRIL 2928 AVENIDA TRIUNVIRATO 4038 AVENIDA TRIUNVIRATO 3748 ALMAGRO AVENIDA CORRIENTES 3667 CALLE GUARDIA VIEJA 3593 AVENIDA CORRIENTES 3891 AVENIDA CORRIENTES 4486 AVENIDA CORRIENTES 3499 CALLE GASCON 592 CALLE FRANCISCO ACUÑA DE FIGUEROA 411 CALLE QUITO 3602 AVENIDA CASTRO BARROS 8 CALLE QUINTINO BOCAYUVA 401 AVENIDA MEDRANO 570 BALVANERA AVENIDA JUJUY 42 CALLE DOCTOR LUIS PASTEUR 674 CALLE LAVALLE 2999 CALLE ADOLFO ALSINA 2696 CALLE HIPOLITO YRIGOYEN 1963 CALLE 24 DE NOVIEMBRE 116 CALLE MORENO 2494 CALLE JUNIN 386 CALLE RIOBAMBA 188 AVENIDA INDEPENDENCIA 2443 CALLE ALBERTI 113 CALLE DOCTOR JUAN JOSE PASO 391 AVENIDA CORRIENTES 1903 CALLE SÁNCHEZ DE LORIA 188 CALLE TENIENTE GRAL. JUAN DOMINGO PERON 2312 CALLE SARMIENTO 1887 AVENIDA CORDOBA 2502 CALLE HIPOLITO YRIGOYEN 1890 AVENIDA RIVADAVIA 1827 AVENIDA CORDOBA 2212 CALLE MORENO 1962 AVENIDA RIVADAVIA 2187 CALLE VENEZUELA 2793 CALLE COMBATE DE LOS POZOS 376 BARRACAS AVENIDA MONTES DE OCA 657 AVENIDA REGIMIENTO DE PATRICIOS 495 CALLE CALIFORNIA 1515 AVENIDA MONTES DE OCA 1399 AVENIDA MARTIN GARCIA 507 BELGRANO CALLE MONTAÑESES 2015 CALLE CIUDAD DE LA PAZ 2087 CALLE BLANCO ENCALADA 2360 CALLE 11 DE SEPTIEMBRE DE 1888 4652 CALLE MOLDES 1809 CALLE CONGRESO 1862 CALLE DOCTOR PEDRO IGNACIO RIVERA 2430 CALLE MOLDES 2873 CALLE VIRREY DEL PINO 2407 CALLE ESTEBAN ECHEVERRIA 3185 CALLE AMENABAR 2687 AVENIDA MONROE 2487 BOCA CALLE MINISTRO BRIN 501 CALLE PINZON 452 AVENIDA REGIMIENTO DE PATRICIOS 146 BOEDO AVENIDA -

Park Hyatt Buenos Aires

TOURS & ACTIVITIES BUENOS AIRES PALACIO DUHAU – PARK HYATT BUENOS AIRES HALF DAY ACTIVITIES CITY TOUR Discover the most attractive areas of Buenos Aires led by an expert, such as 9 de Julio Avenue, the Obelisk, Plaza de Mayo, San Telmo, La Boca and Recoleta. This tour will introduce you to a wide array of Buenos Aires neighborhoods and points of interest. WALKING TOUR AT RECOLETA Enjoy a pleasant break while you stroll at Recoleta, the DISTRICT most aristocratic and upper-class area in town. You will have time to relax, walk around, have a coffee at one of the most traditional cafés in the area and you will visit the Recoleta cemetery with an insight of our history. EVITA PERÓN TOUR Contemporary Argentina cannot be understood without acknowledging the peronista emergence and its consequences. The tour visits the sites that can somehow explain the political and cultural conflicts that were brought about by the emergence of Juan D. Perón at the political arena. The tour focuses on Eva Duarte, her political performance, her tragic death and the continuity of her myth to these days. Some of the key sceneries of her life are here visited as well as the place where her corpse was mummified and the museum opened to commemorate her legacy. This tour is not politically based and aims to recreate the life of Evita, a world-known character of our history. POPE FRANCIS TOUR This tour recreates the life of Pope Francis and all his work. You will be able to get to know who Jorge Mario Bergoglio is, by knowing the simplicity he lived in: his neighborhood, where he attended school and the churches where he was baptized and heard God’s call.