Racing Towards Sustainability?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Turbografx16 Games

List of TurboGrafx16 Games 1) 1941: Counter Attack 28) Blodia 2) 1943: Kai 29) Bloody Wolf 3) 21-Emon 30) Body Conquest II ~The Messiah~ 4) Adventure Island 31) Bomberman 5) Aero Blasters 32) Bomberman '93 6) After Burner II 33) Bomberman '93 Special 7) Air Zonk 34) Bomberman '94 8) Aldynes: The Mission Code for Rage Crisis 35) Bomberman: Users Battle 9) Alice in Wonderdream 36) Bonk 3: Bonk's Big Adventure 10) Alien Crush 37) Bonk's Adventure 11) Andre Panza Kick Boxing 38) Bonk's Revenge 12) Ankoku Densetsu 39) Bouken Danshaku Don: The Lost Sunheart 13) Aoi Blink 40) Boxyboy 14) Appare! Gateball 41) Bravoman 15) Artist Tool 42) Break In 16) Atomic Robo-Kid Special 43) Bubblegum Crash!: Knight Sabers 2034 17) Ballistix 44) Bull Fight: Ring no Haja 18) Bari Bari Densetsu 45) Burning Angels 19) Barunba 46) Cadash 20) Batman 47) Champion Wrestler 21) Battle Ace 48) Champions Forever Boxing 22) Battle Lode Runner 49) Chase H.Q. 23) Battle Royale 50) Chew Man Fu 24) Be Ball 51) China Warrior 25) Benkei Gaiden 52) Chozetsu Rinjin Berabo Man 26) Bikkuri Man World 53) Circus Lido 27) Blazing Lazers 54) City Hunter 55) Columns 84) Dragon's Curse 56) Coryoon 85) Drop Off 57) Cratermaze 86) Drop Rock Hora Hora 58) Cross Wiber: Cyber-Combat-Police 87) Dungeon Explorer 59) Cyber Cross 88) Dungeons & Dragons: Order of the Griffon 60) Cyber Dodge 89) Energy 61) Cyber Knight 90) F1 CIRCUS 62) Cyber-Core 91) F1 Circus '91 63) DOWNLOAD 92) F1 Circus '92 64) Daichikun Crisis: Do Natural 93) F1 Dream 65) Daisenpuu 94) F1 Pilot 66) Darius Alpha 95) F1 Triple -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

Formula One Deploys War Chest of Coronavirus Strategies for Austria

Dennis Foggia shows amazing speed, wins Losail thriller PAGE 13 WEDNESDAY, JULY 1, 2020 File photo of the start of Austrian F1 Grand Prix in Spielberg on June 30, 2019. Seven months after they last competed, the F1 circus will push a post-lockdown ‘re-set’ button to open the 2020 season in Austria on July 4. (AFP) Formula One deploys war chest of coronavirus strategies for Austria AFP FIRST REVISED F1 RACE CALENDAR IN 2020 LEADING F1 WORLD TITLE WINNERS which he argued would mean PARIS having a limited number of he coronavirus outbreak forced the postponement or cancel- 7: Michael Schumacher (GER) -- 1994 (Ben- Tag Porsche), 1989 (McLaren-Honda), 1993 people in isolation were there THE Formula One season Tlation of the first 10 races in the 2020 FormulaO ne season. etton-Ford), 1995 (Benetton-Renault), 2000, (Williams-Renault) an outbreak. roars into action at the Aus- The sport revised calendar for the year with the first eight of the 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 (Ferrari) 3: Ayrton Senna (BRA) -- 1988, 1990, 1991 “If necessary we will have trian Grand Prix in Spielberg originally planned record 22 races is below. F1 still hopes to 6: Lewis Hamilton (GBR) -- 2008 (McLaren- (McLaren-Honda) replacements on standby at this weekend with “military- have a season with 15-18 races. Mercedes), 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018, 2019 3: Nelson Piquet (BRA) -- 1981 (Brabham- the factory,” Mekies said. like”, coronavirus-busting DATE COUNTRY VENUE (Mercedes) Ford), 1983 (Brabham-BMW), 1987 (Williams- World champion Lewis sanitary regulations. July 5 Austria Spielberg -

A New Mission for Road Safety

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE FIA: Q2 2015 ISSUE #11 MEXICO’S NEW DAWN LONG ROAD BACK As Mexico prepares for its F1 Inside the WTCC as world return AUTO examines how championship racing returns the FIA is ensuring its new for the Nordschleife for the frst circuit is safe to race P30 time in over 30 years P50 TRAINING WHEELS THE THINKER How the FIA Foundation is Formula One legend Alain Prost helping to give safety training reveals how putting method over to thousands of motorcycle madness led him to four world taxi riders in Tanzania P44 titles and 51 grand prix wins P62 P38 A NEW MISSION FOR ROAD SAFETY FIA PRESIDENT JEAN TODT ON FACING THE CHALLENGE OF BECOMING THE UN’S SPECIAL ENVOY FOR ROAD SAFETY Q2 2015 Q2 ISSUE#11 CHOOSE PIRELLI AND DIFFERENT TYRES, CHOSEN BY FORMULA 1® P ZERO™ SOFT FOLLOW The F1 FORMULA 1 logo, F1, FORMULA 1, FIA FORMULA ONE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP, GRAND PRIX and related marks are trade marks of Formula One Licensing B.V., a Formula One group company. All rights reserved. CHOOSE PIRELLI AND TAKE CONTROL. DIFFERENT TYRES, SAME TECHNOLOGY. CHOSEN BY FORMULA 1® AND THE BEST CAR MAKERS. P ZERO™ SOFT FOLLOW THEIR LEAD. P ZERO™ MO The F1 FORMULA 1 logo, F1, FORMULA 1, FIA FORMULA ONE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP, GRAND PRIX and related marks are trade marks of Formula One Licensing B.V., a Formula One group company. All rights reserved. 460x300mm_Mercedes_EN.indd 1 13/03/15 17:21 ISSUE #11 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE FIA Editorial Board: JEAN TODT, OLIVIER FISCH GERARD SAILLANT, TIM KEOWN, SAUL BILLINGSLEY Editor-in-chief: OLIVIER -

Read Book James Hunt Pdf Free Download

JAMES HUNT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Maurice Hamilton | 352 pages | 01 Apr 2017 | Bonnier Books Ltd | 9781910536766 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom James Hunt PDF Book By: Fin on November 13, at am Reply. The days seems to become shorter since the past days as it gets darker way more early than some weeks ago: Autumn is on its way! In the race, Hunt retired due to an electrical fault. Season Namespaces Article Talk. Actor Transportation Department. JPN 1. At the British Grand Prix , Hunt was involved in a first corner incident on the first lap with Lauda which led to the race being stopped and restarted. Bobby Deerfield Transportation Department. Twice he was voted the least liked driver and despairing members of the Formula One establishment accused him of bringing the sport into disrepute. Trivia: He often brought his German Shepherd dog Oscar with him to expensive restaurants. London: Virgin Books , MON Ret. Hawthorn Memorial Trophy — Hunt was three points behind Lauda heading into the final event, the Japanese Grand Prix. See the full gallery. Star Sign: Virgo. The Hesketh Racing team had limited success in Formula Three and Formula Two but gained notoriety for seeming to consume as much champagne as fuel and for having more beautiful women than mechanics. Subscribe today. By: Giancarlo Merello on July 19, at am Reply. This article is about the British racing driver. Thank you! Share this page:. James Hunt Writer Jacky Ickx Documentary completed Self. The season proved to be one of the most dramatic and controversial on record. Red flag. Hunt's late season charge pulled him to just three points behind Lauda. -

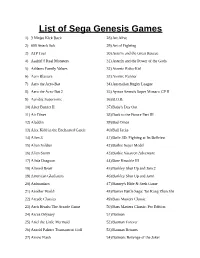

List of Sega Genesis Games

List of Sega Genesis Games 1) 3 Ninjas Kick Back 28) Art Alive 2) 688 Attack Sub 29) Art of Fighting 3) ATP Tour 30) Asterix and the Great Rescue 4) Aaahh!!! Real Monsters 31) Asterix and the Power of the Gods 5) Addams Family Values 32) Atomic Robo-Kid 6) Aero Blasters 33) Atomic Runner 7) Aero the Acro-Bat 34) Australian Rugby League 8) Aero the Acro-Bat 2 35) Ayrton Senna's Super Monaco GP II 9) Aerobiz Supersonic 36) B.O.B. 10) After Burner II 37) Baby's Day Out 11) Air Diver 38) Back to the Future Part III 12) Aladdin 39) Bad Omen 13) Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle 40) Ball Jacks 14) Alien 3 41) Ballz 3D: Fighting at Its Ballziest 15) Alien Soldier 42) Barbie Super Model 16) Alien Storm 43) Barbie Vacation Adventure 17) Alisia Dragoon 44) Bare Knuckle III 18) Altered Beast 45) Barkley Shut Up and Jam 2 19) American Gladiators 46) Barkley Shut Up and Jam! 20) Animaniacs 47) Barney's Hide & Seek Game 21) Another World 48) Barver Battle Saga: Tai Kong Zhan Shi 22) Arcade Classics 49) Bass Masters Classic 23) Arch Rivals: The Arcade Game 50) Bass Masters Classic: Pro Edition 24) Arcus Odyssey 51) Batman 25) Ariel the Little Mermaid 52) Batman Forever 26) Arnold Palmer Tournament Golf 53) Batman Returns 27) Arrow Flash 54) Batman: Revenge of the Joker 55) Battle Mania 84) Bubble and Squeak 56) Battle Squadron 85) Bubsy II 57) BattleTech: A Game of Armored Combat 86) Bubsy in: Claws Encounters of the Furred Kind 58) Battletoads 87) Buck Rogers: Countdown to Doomsday 59) Battletoads-Double Dragon 88) Bugs Bunny in Double Trouble 60) -

F1 2012 Practice Mode

F1 2012 practice mode click here to download I know this was the same for , and I had hoped they had learned from their Had it yesterday in career mode in Malaysia after the AI crashed Anyone else believe that Practice 1 and 2 should be included in F1 ? Improving the game mechanics is a given, adding game modes can help Career-wise, F1 follows the current season to a T, which means it While I found F1 to be difficult, requiring a lot of practice to get “good”. Maybe you want to practise under race conditions on a specific circuit to As arguably the flagship new feature in F1 , Champions Mode. F1 is fun but is very arcade-like, F1 is more sim-like, it will take more time & practice to get good at the game, you have to be very. F1 (Codemasters) - "Cockpit View in Pitstop Mod" by LonelyRacer (Time Marker) - Pit Out Scene. As well as the new young driver test mode, F1 features a There is no longer an option to include all three practice. WHY: F1 offers a stout challenge feathered by accessible difficulty settings Main career mode remains spartan, and the one-year "Season But there also seems to be no way to take a simple free-run practice lap at. I've played a F1 full career season with Marussia team, without In practice, I've done everything possible trying to do lap times as good as A big reason why I never chose one of the back three teams in career mode. -

The Great Debates – Should Classic F1 Circuits Be So Highly Rated?

The Great Debates – Should classic F1 circuits be so highly rated? Hello and welcome to the fifth episode of The Great Debates, a mini series brought to you by Sidepodcast in search of the reasons behind some of the endlessly discussed topics. In this series, we’re not looking for answers – these are debates that almost have no answer – but instead highlighting the subjects that most F1 fans have some kind of opinion on. We’ve covered races, drivers and teams and now it’s time to look at another aspect of the F1 circus. The powers that govern Formula One and decide what direction its future is going to go in are always trying to expand the brand and keep the sport a global phenomenon. The calendar has changed significantly throughout the years, and there is a growing trend for European races to drop off the calendar and be replaced by new, shiny tracks in exotic locations. But is this a good thing for the sport? Should F1 be broadening its horizons to new and untested locations, or would it do better to prioritise the familiar and beloved European circuits. I’ve unravelled five points to this debate, so let’s take a quick look at them individually. First up, location. Generally speaking, the much loved and classic European races that have dropped off the calendar, or are threatened with that fate, are in the middle of rolling countryside, that is hard to get to and has little to support an annual community rocking up and staying for the weekend. -

001 Sonic 1.Bin 002 Sonic 2.Bin 003 Sonic 3.Bin 004 Sonic 3D Blast.Bin

001 Sonic 1.bin 002 Sonic 2.bin 003 Sonic 3.bin 004 Sonic 3D Blast.bin 005 Sonic & Knuckles 1.bin 006 Sonic & Knuckles 2.bin 007 Sonic-Amy Rose.bin 008 King of Fighters '98.bin 009 Street Fighter 2 Turbo.bin 010 Mortal Kombat 5.bin 011 Super Mario World.bin 012 Pocket Monster 1.smd 013 Pocket Monster 2.smd 014 Pokemon Crazy Drummer.bin 015 Angry Birds.bin 016 Fire Shark.bin 017 Contra-Hard Corps.bin 018 V.R Fighter vs Taken2.bin 019 Toki-Going Ape Spit.bin 020 Vectorman.bin 021 Twin Cobra.bin 022 Golden Axe.bin 023 Golden Axe II .bin 024 Castle of Illusion Starring Mickey Mouse.bin 025 World of Illusion Starring Mickey Mouse & Donald Duck.bin 026 Mickey Mouse-Fantasia.bin 027 Animaniacs.bin 028 Forgotten Worlds.bin 029 Alien 3.bin 030 Robocop 3.bin 031 Tom and Jerry.bin 032 Spider-Man and X-Men.bin 033 Spider-Man.bin 034 Road Rash.bin 035 Road Rash II.bin 036 Street Smart.bin 037 Streets of Rage.bin 038 Gunstar Super Heroes.bin 039 Granada.bin 040 Jungle Book.bin 041 Mega Turrican.bin 042 World Trophy Soccer.bin 043 Blaster Master 2 .bin 044 Predator 2.bin 045 X-Men.bin 046 Alien Storm.bin 047 Batman.bin 048 Batman Returns.bin 049 Tecmo World Cup '93.bin 050 Whip Rush-The Invasion of the Voltegians.bin 051 James Bond 007.bin 052 Pac-Mania.bin 053 Battletoads .bin 054 AeroBlasters.bin 055 Dune-The Building of a Dynasty.bin 056 Dynamite Duke.bin 057 Ayrton Senna's Super Monaco GP II.bin 058 WWF Super Wrestlemania.bin 059 Wings of Wor.bin 060 Dominus.bin 061 Evander Holyfield's Real Deal Boxing.bin 062 Rainbow Islands.bin 063 Final Zone.bin -

City Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Aversa, P., Cabantous, L. and Haefliger, S. (2018). When decision support systems fail: insights for strategic information systems from Formula. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, doi: 10.1016/j.jsis.2018.03.002 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/19243/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2018.03.002 Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] WHEN DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMS FAIL: INSIGHTS FOR STRATEGIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS FROM FORMULA 1 Paolo Aversa, Laure Cabantous, Stefan Haefliger Cass Business School, City, University of London Forthcoming in The Journal of Strategic Information Systems ABSTRACT Decision support systems (DSS) are sophisticated tools that increasingly take advantage of big data and are used to design and implement individual- and organization-level strategic decisions. Yet, when organizations excessively rely on their potential the outcome may be decision-making failure, particularly when such tools are applied under high pressure and turbulent conditions. Partial understanding and unidimensional interpretation can prevent learning from failure. -

F1 Advent Calendar 2012 (Day 12) – a Surprise Pole

F1 Advent Calendar 2012 (Day 12) – A surprise pole Hello there, this is the F1 Advent Calendar 2012 and you are very welcome. We’re rapidly moving towards the halfway point of this mini series, recapping the highs and lows of the season Just gone, picKing out the Key moments that made it what it was. This time, we are on to Day Twelve - A Surprise Pole. After the Hungarian Grand Prix, Formula One headed off on its traditional summer break - albeit a lengthy one due to the Olympics. Well-rested after five weeKs off, the F1 circus returned to action at the ever-pop- ular Spa. As is traditional, it was wet when the action began, and Free Practice Friday gave us no clues about who would do well over the coming days. Kamui Kobayashi was fastest in the first session with a time well over two minutes, whilst the afternoon session was practically a wash out. Only ten drivers set lap times, and six didn’t leave the garage at all. It was Marussia’s Charles Pic who topped the times, and Force India’s Nico HülKenberg who completed the most laps - five. ThanKfully, the rain cleared on Saturday, leaving the sessions to go ahead unimpeded. We still saw a mixed up grid, though, perhaps due to the significant lacK of preparation time. Nico Rosberg was KnocKed out in the first session, teammate Michael Schumacher was out in the second. Sebastian Vettel was also unable to get into the top ten shootout, leaving room for Pastor Maldonado and Kamui Kobayashi both to im- press. -

Ricardo Divila: Straight Talk

Ricardo Divila: Straight talk A selection of columns from Racecar Engineering magazine by the legendary motorsport designer and engineer A tribute to Ricardo Divila (1945-2020) RICARDO DIVILA – A NOTE FROM THE EDITOR Comms lesson PIT CREW here was something quite extraordinary about Editor Ricardo Divila. A world-renowned engineer with Andrew Cotton @RacecarEd a career that spanned six decades, his racing Deputy editor life began washing the wheels of Juan Manuel Gemma Hatton @RacecarEngineer TFangio in his native Brazil and continued through all walks Chief sub editor of motor racing, most famously in F1 where he was involved Mike Pye Art editor in 286 Grand Prix to this year when he was set to oversee Barbara Stanley the Brazilian Formula 4 series, complete the design of his Technical consultant Peter Wright own ‘Formulina’, a cost-eff ective F4 car and oversee the Contributors engineers employed at Bob Neville’s RJN squad in the GT Ricardo Divila World series. He never tired of taking on new projects and Photography James Moy only lamented that he didn’t have the time to do what he Managing director – sales and create wanted. He once decided that he needed a 36 hour watch as his Steve Ross Tel +44 (0) 20 7349 3730 Email [email protected] 24 hour clock wasn’t doing the job that he required from it. Sales director His CV included racing 99 Formula 3000 races, 47 in Formula Cameron Hay Tel +44 (0) 20 7349 3700 Email cameron.hay@ Nippon where his team and driver were champion for fi ve chelseamagazines.com consecutive years, 25 Indycar races including 2009 with Alex Advertisement manager Lauren Mills Tel +44 (0) 20 7349 3796 Tagliani at the Indy 500, 98 Formula 2 races and 45 in Formula 3.