Squash Bug (Hemiptera: Coreidae): Biology and Management in Cucurbitaceous Crops

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squash Bug, Anasa Tristis (Degeer)1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. EENY-077 Squash Bug, Anasa tristis (DeGeer)1 John L. Capinera2 Introduction Egg The squash bug, Anasa tristis, attacks cucurbits Eggs are deposited on the lower surface of (squash and relatives) throughout Central America, leaves, though occasionally they occur on the upper the United States, and southern Canada. Several surface or on leaf petioles. The elliptical egg is related species in the same genus coexist with squash somewhat flattened and bronze in color. The average bug over most of its range, feeding on the same plants egg length is about 1.5 mm and the width about 1.1 but causing much less injury. mm. Females deposit about 20 eggs in each egg cluster. Eggs may be tightly clustered (Figure 1) or Life Cycle spread a considerable distance apart, but an equidistant spacing arrangement is commonly The complete life cycle of squash bug commonly observed. Duration of the egg stage is about seven to requires six to eight weeks. Squash bugs have one nine days. generation per year in northern climates and two to three generations per year in warmer regions. In Nymph intermediate latitudes the early-emerging adults from the first generation produce a second generation There are five nymphal instars. The nymphal whereas the late-emerging adults go into diapause. stage requires about 33 days for complete Both sexes overwinter as adults. The preferred development. The nymph is about 2.5 mm in length overwintering site seems to be in cucurbit fields when it hatches, and light green in color. -

Organic Options for Striped Cucumber Beetle Management in Cucumbers Katie Brandt Grand Valley State University

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Masters Theses Graduate Research and Creative Practice 6-2012 Organic Options for Striped Cucumber Beetle Management in Cucumbers Katie Brandt Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Brandt, Katie, "Organic Options for Striped Cucumber Beetle Management in Cucumbers" (2012). Masters Theses. 29. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORGANIC OPTIONS FOR STRIPED CUCUMBER BEETLE MANAGEMENT IN CUCUMBERS Katie Brandt A thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of GRAND VALLEY STATE UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Biology June 2012 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to my advisors, who helped me plan this research and understand the interactions of beetles, plants and disease in this system. Jim Dunn helped immensely with the experimental design and prevented me from giving up when my replication block was destroyed in a flood. Mathieu Ngouajio generously shared his expertise with organic vegetables, field trials and striped cucumber beetles. Mel Northup lent the HOBO weather stations, visited the farm to instruct me to set them up and later transferred the data into an Excel spreadsheet. Sango Otieno and the students at the Statistical Consulting Center at GVSU were very helpful with data analysis. Numerous farmworkers and volunteers also helped in the labor-intensive process of gathering data for this research. -

Squash Bug, Anasa Tristis

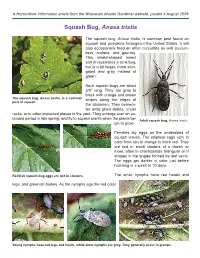

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 4 August 2008 Squash Bug, Anasa tristis The squash bug, Anasa tristis, is common pest found on squash and pumpkins throughout the United States. It will also occasionally feed on other curcurbits as well (cucum- bers, melons, and gourds). This shield-shaped insect sort of resembles a stink bug, but is a bit larger, more elon- gated and gray instead of green. Adult squash bugs are about 5/8” long. They are gray to black with orange and brown The squash bug, Anasa tristis, is a common stripes along the edges of pest of squash. the abdomen. They overwin- ter amid plant debris, under rocks, or in other protected places in the yard. They emerge over an ex- tended period in late spring, and fl y to squash plants when the plants be- Adult squash bug, Anasa tristis. gin to grow. Females lay eggs on the undersides of squash leaves. The elliptical eggs vary in color from tan to orange to brick red. They are laid in small clusters of a dozen or more, often in characteristic triangular or V shapes in the angles formed by leaf veins. The eggs get darker in color just before hatching in a week to 10 days. Reddish squash bug eggs are laid in clusters. The small nymphs have red heads and legs, and greenish bodies. As the nymphs age the red color Young nymphs have red legs and heads, while older nymphs are grey. They generally occur in groups. turns to black, and the older ones look like they are covered with a grainy gray powder. -

Anasa Tristis) Can Be a Serious Insect Pest for Organic Summer Squash Growers

EFFECTS OF COVER CROPS AND ORGANIC INSECTICIDES ON SQUASH BUG (ANASA TRISTIS) POPULATIONS by LINDSAY NICHOLE DAVIES (Under the Direction of David Berle) ABSTRACT Squash bugs (Anasa tristis) can be a serious insect pest for organic summer squash growers. The purpose of this research was to evaluate two methods to control A. tristis populations. The first experiment involved planting cover crops adjacent to summer squash in an effort to attract natural enemies to keep A. tristis populations in check. Natural enemies were attracted to the plots, but did not significantly reduce A. tristis populations. This may have been due to other food sources in the plots, such as pollen, nectar, and aphids. Also, summer squash yields were negatively affected by the cover crop treatments. The second experiment involved evaluating the efficacy of organic insecticides on A. tristis adults and nymphs. Results of this study showed pyrethrin-based sprays are best for controlling A. tristis. INDEX WORDS: Summer squash, Diversified planting, Natural enemies, Pesticides, Organic agriculture, Sustainable agriculture, Biological control EFFECTS OF COVER CROPS AND ORGANIC INSECTICIDES ON SQUASH BUG (ANASA TRISTIS) POPULATIONS by LINDSAY NICHOLE DAVIES B.S., Indiana University, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Lindsay Nichole Davies All Rights Reserved EFFECTS OF COVER CROPS AND ORGANIC INSECTICIDES ON SQUASH BUG (ANASA TRISTIS) POPULATIONS by LINDSAY NICHOLE DAVIES Major Professor: David Berle Committee: Paul Guillebeau Elizabeth Little Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my friends, family, and fiancé. -

The Importance of Environmentally-Acquired Bacterial Symbionts for the Squash Bug (Anasa Tristis), a Significant Agricultural Pest

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.14.452367; this version posted July 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The importance of environmentally-acquired bacterial symbionts for the squash bug (Anasa tristis), a significant agricultural pest Tarik S. Acevedo1, Gregory P. Fricker1, Justine R. Garcia1,2, Tiffanie Alcaide1, Aileen Berasategui1, Kayla S. Stoy, Nicole M. Gerardo1* 1Department of Biology, Emory University, 1510 Clifton Road, Atlanta, GA, 30322, USA 2Department of Biology, New Mexico Highlands University, 1005 Diamond Ave, Las Vegas, NM, 87701, USA *Correspondence: Nicole Gerardo [email protected] Keywords: squash bugs, Cucurbit Yellow Vine Disease, Coreidae, symbiosis, Caballeronia bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.14.452367; this version posted July 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 InternationalCaballeronia license. -Squash Bug Symbiosis ABSTRACT Most insects maintain associations with microbes that shape their ecology and evolution. Such symbioses have important applied implications when the associated insects are pests or vectors of disease. The squash bug, Anasa tristis (Coreoidea: Coreidae), is a significant pest of human agriculture in its own right and also causes damage to crops due to its capacity to transmit a bacterial plant pathogen. -

Egg Viability and Larval Penetration in Trichopoda Pennipes Pilipes Mohammad Shahjahan2 and John W. Beardsley, Jr.3 Trichopoda P

Vol. XXII, No. 1, August, 1975 '33 Egg Viability and Larval Penetration in Trichopoda pennipes pilipes Fabricius (Diptera: Tachinidae)1 Mohammad Shahjahan2 and John W. Beardsley, Jr.3 Trichopoda pennipes pilipes Fabricius was introduced into Hawaii from Trinidad in 1962 to combat the southern green stink bug, Nezara viridula (Fabricius) (Davis and Krauss, 1963; Davis, 1964). In Hawaii, T. p. pilipes has been reared from the scutellerid Coleotichus blackburni White and the pentatomids Thyanta accera (McAtee) and Plautia stali Scott, in addition to N. viridula. During 1965 we began a study on the biology of T. p. pilipes in rela tion to its principal host in Hawaii, N. viridula. Laboratory experiments and observations were conducted to evaluate the effects of superparasiti- zation of N. viridula by the tachinid on both the host and parasite pop ulations. The results of some of this work were reported previously (Shahjahan, 1968). The present paper summarizes data which were ob tained on parasite egg viability and larval penetration of host integument. The methods used in rearing and handling both N. viridula and T. p. pilipes were described in the earlier paper (Shahjahan, 1968). Supernumerary Oviposition and Egg Viability Adults of the southern green stink bug often are heavily superpara- sitized by T. p. pilipes, both in the field and under laboratory conditions. As many as 237 T. p. pilipes eggs were counted on a single field-collected stink bug, and a high of 275 eggs were deposited on one bug in the lab oratory (Shahjahan, 1968). Eggs are placed predominantly on the venter of the thorax, but may be deposited on almost any part of the host, in cluding the appendages, wings, eyes, etc. -

Squash Bugs of South Dakota Burruss Mcdaniel South Dakota State University

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletins SDSU Agricultural Experiment Station 1989 Squash Bugs of South Dakota Burruss McDaniel South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_tb Part of the Entomology Commons, and the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation McDaniel, Burruss, "Squash Bugs of South Dakota" (1989). Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletins. 12. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_tb/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the SDSU Agricultural Experiment Station at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T B 92 quash Agricultural Experiment Station South Dakota State University U.S. Department of Agriculture T B 92 of South Dakota Burruss McDaniel Professor, Plant Science Department South Dakota State University COREi DAE (HEMIPTERA: HETEROPTERA) Agriopocorinae (this latter extrazimital) . Baranowski and Slater ( 1986), in their Coreidae of Florida, listed The family Coreidae is best known because of the 120 species dispersed among 18 genera, 9 tribes and 3 destructive habit of the squash bug, Anasa tristis, on subfamilies. squash, pumpkin, cucumber, and other members of the cucurbit family in the United States. The family, The material examined in this work is deposited in represented by various species, is found throughout the the SDSU H.C. -

REPRODUCTIVE BIONOMICS of the SQUASH BUG, Anasa ~ (HETEROPTERA: COREIDAE) AS AFFECTED by TEMPERATURE by All ABBAS ~L-OBAIDI Bach

REPRODUCTIVE BIONOMICS OF THE SQUASH BUG, Anasa ~ (HETEROPTERA: COREIDAE) AS AFFECTED BY TEMPERATURE By All ABBAS ~L-OBAIDI Bachelor of Science University of Baghdad Baghdad, Iraq 1977 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December, 1987 Th~~ \ 9'l1 At.Js-3.... c ~ P· Q.. REPRODUCTIVE BIONOMICS OF THE SQUASH BUG, Anasa ~ (HETEROPTERA: COREIOAE) AS AFFECTED BY TEMPERATURE Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii 1290861 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere thanks and appreciation to my adviser, Dr. W. Scott Fargo, for his continued guidance, motivation, friendship, and assistance in all aspects of this study. I would also like to thank Dr. S. Fox and D. J. Webster for serving on my advisory committee. Their advice and insightful review of the manuscript are greatly appreciated. I express my gratitude to Dr. David Weeks, Professor of Statistics, for his guidance, helpful suggestions, and assistance in statistical analyses. A very special thanks is extended for Mr. Edmond Bonjour. His friendly assistance in the field, laboratory, and with the analysis is appreciated. I am also greatful to many fellow graduate students for the help and friendship each provided. Greatful acknowledgement is given to my country, my father, sisters and brothers, for their financial support and love. Special love and thanks go to my youngest brother, Abdul-Rahman, who supported me with hope and friendship. My appreciation is expressed to my wife, Sammeiria, and our sons, Saief and Zaid, who have encouraged me and made many sacrifices throughout this study. -

Trade-Offs and Synergies in Management of Two Co-Occurring

Journal of Pest Science https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-021-01379-y ORIGINAL PAPER Trade‑ofs and synergies in management of two co‑occurring specialist squash pests Lauren J. Brzozowski1 · Donald C. Weber2 · Anna K. Wallingford3 · Michael Mazourek1 · Anurag A. Agrawal4,5 Received: 19 October 2020 / Revised: 24 March 2021 / Accepted: 16 April 2021 © The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2021 Abstract Co-occurring herbivorous pests may have shared or divergent responses to plant- and insect- derived cues, creating chal- lenges for efective pest management in agroecosystems. We examined how behaviors of two endemic specialist herbivores of Cucurbitaceae crops, squash bugs (Anasa tristis, Hemiptera: Coreidae) and striped cucumber beetles (Acalymma vittatum, Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) are afected by cues in the Cucurbita pepo agroecosystem. We evaluated plant resistance to squash bugs and beetles using cultivars that typify the two domesticated subspecies C. p. pepo (e.g., zucchini) and C. p. ovifera (e.g., straightneck summer squash), and tested how squash bugs respond to beetle aggregation and feeding. Across several feld experiments, we demonstrated that squash bugs prefer to oviposit on C. p. ovifera over C. p. pepo, while beetles had the opposing preference. Nonetheless, there was no link between preference and squash bug nymphal survival or develop- ment. While squash bugs and beetles diverge in preference, we found that squash bugs positively respond to beetle-derived cues. More squash bug oviposition was observed on plants with greater beetle damage and, using both actively feeding beetles and synthetic lures, we demonstrate that bugs eavesdrop on and respond to vittatalactone, the male-produced beetle aggregation pheromone. -

Download This Newsletter in Pdf Format

College of Agricultural, Consumer, and Environmental Sciences Illinois Fruit and Vegetable News Vol. 12, No. 9, June 22, 2006 a newsletter for commercial growers of fruit and vegetable crops "We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit." Aristotle Address any questions or comments regarding this newsletter to the individual authors listed after each article or to its editor, Rick Weinzierl, 217-333-6651, [email protected]. The Illinois Fruit and Vegetable News is available on the web at: http://www.ipm.uiuc.edu/ifvn/index.html . To receive email notification of new postings of this newsletter, call or write Rick Weinzierl at the number or email address above. For your calendar … September 8, 2006 -- Illinois Pumpkin Field Day will be held at the University of Illinois Vegetable Research Farm near Champaign, IL. In this issue ... Regional Updates (from Maurice Ogutu) Degree-day Accumulations Notes from Chris Doll (fruit crop phenology, Summer Orchard Day, peach yields, calcium applications) Fruit Production and Pest Management (fire blight and apple scab, codling moth phenology, rates for Assail and Rimon, historical observations) Vegetable Production and Pest Management (corn borer and earworm, western bean cutworm, squash vine borer and squash bug, phytophthora blight of cucurbits) University of Illinois Extension Specialists in Fruit & Vegetable Production & Pest Management Regional Updates In northern Illinois, the last two weeks have brought mostly sunny days with average day temperatures in the low 60s to low 90s and night temperatures in the upper 40s to low 70s. The highest temperature during this period was recorded on June 18, 2006 when day temperatures were in the 90s and night temperatures in the 70s. -

![1924] the BIOLOGY of TRICHOPODA PENNIPES FAB. (DIPTERA, Tachinidze)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2056/1924-the-biology-of-trichopoda-pennipes-fab-diptera-tachinidze-3292056.webp)

1924] the BIOLOGY of TRICHOPODA PENNIPES FAB. (DIPTERA, Tachinidze)

1924] The Biology of Trichopoda pennipes Fab. 7 THE BIOLOGY OF TRICHOPODA PENNIPES FAB. (DIPTERA, TACHINIDzE), A PARASITE OF THE COMMON SQUASH BUG.* BY HARLAN . WORTHLEY. Massachusetts Agricultural Experiment Station, Amherst, Mass. PART I. INTRODUCTION. The common squash bug, Anasa tristis de Geer, is an ever- present and often troublesome pest in Massachusetts, and has been a subject for investigation at the Massachusetts Agri- cultural Experiment Station for the past three years. While studying the life history and habits of this pest, the writer dis- covered abundant evidence of the presence and activity of the parasite Trichopoda pennipes. A review of the literature showed that comparatively little is known of the life history and habits of this beneficial fly. Much to the surprise of the writer, in view of his own observations, it was found that some authors have even intimated that little good is derived by mankind from the work of this supposedly beneficial species. Failure of the written records to substantiate observations of the writer furnished the initial stimulus to a study of the habits of the fly, the object of this study being to discover the exact relationship existing between parasite and host. A portion of the following account is the result of these studies. During the course of the work it was found necessary to confine adults of both sexes in the same cage to induce mating. Some difficulty was experienced at first in determining the sex *Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science at the Massachu- setts Agricultural College, and published with the consent of the Director of the Graduate School. -

Issued March 28, 2018

Hexapod Herald March 28, 2018 Retreat Entomology faculty gather to share ideas and experience the UGA Griffin campus Entomology faculty gathered in Griffin to ex- change ideas, update each other on program- matic themes and discuss issues and opportu- nities in teaching. Tours of facilities on the Griffin Campus includ- ed a visit to the Turfgrass Research and Exten- sion Complex, Plant Genetics Resources and Conservation unit, and the new FoodPic (Food Product, Innovation and Commercialization) Center building. Part of the event was held in the Research and Education Garden, a unique 60 acre facility ad- jacent to the campus. Results from interdisci- plinary research projects are often incorpo- rated into theme gardens within the Demon- stration Areas for visitors to view and experi- ence http://caes2.caes.uga.edu/campus/ griffin/garden/ Photos by Nancy Hinkle http://www.caes.uga.edu/departments/entomology.html From the desk of S. Kristine Braman … Our faculty retreat this month was held on the Griffin Campus. The two-day session included presentations by Gaelen Burke, Jason Schmidt, Brendan Hunt and Shimat Joseph. Updating each other on the accomplishments of these diverse research programs of some of our early-career scientists was a highlight of the meeting. We believe the grand challenges facing our world can be addressed in many ways by gaining a better understanding of insects and their complex roles in our environment. I hope you will take a minute to scan our 2017 publications in this issue which reflect the breadth and balance of our programs here at UGA Entomology. We welcome Dr.