Azores Islands)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Landscapes & Gardens of Madeira & the Azores 2023

Natural Landscapes & Gardens of Madeira & the Azores 2023 20 MAY – 7 JUN 2023 Code: 22313 Tour Leaders Sabrina Hahn, Dr Gerald Luckhurst Physical Ratings Explore the natural landscapes and gardens of Madeira and the Azores including São Miguel, Flores, Terceira, Pico and Faial islands. Overview Accompanied by Sabrina Hahn, horticulturalist, garden writer and ABC radio presenter, explore the natural flora and fauna of Madeira and Azores. In Madeira Sabrina will be joined by landscape architect, Gerald Luckhurst, who has designed and built many gardens on the island. He is an expert plantsman with an unrivalled knowledge of sub- tropical flora an author of the book The Gardens of Madeira. The program includes six moderate nature walks ranging in length from 1.3 to 7.7kms. Visit subtropical Madeira and five volcanic islands from the three geographical groups of the Azores: São Miguel (Eastern Group), Terceira, Faial & Pico (Central Group) & Flores (Western Group). Spend 6 nights based in Funchal, the capital of Madeira; overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, the city is framed by a dramatic backdrop of cloud-tipped mountains and features a wealth of historic monuments. Explore Madeira's abundance of colourful and exotic flora in its parks and gardens including the Quinta do Palheiro and Monte Palace Tropical Gardens; walk some of Madeira's scenic levada (man- made irrigation channels); and view the Laurisilva of Madeira, the largest surviving area of laurel forest containing a unique suite of flora and fauna including many endemic species. Meet Raimundo Quintal, Madeira's leading environmentalist and author of numerous books including the Levadas and Footpaths of Madeira; we visit the Santo da Serra Environmental Education Camp where to learn about the conservation and recovery of the native Laurisilva forest. -

The Best of the Azores

The Best of the Azores 11 October to 21 October, 2017 $2,799 Per Person…based on double occupancy. Includes taxes of approximately 160 USD. 9 Nights with breakfast daily in Terceira, Faial, and Sao Miguel. 16 Meals, including welcome and farewell dinner. Private Tours: Terceira Island Tour, Faial Island Tour, Pico Island Tour with ferry, Sete Cidades Tour, Furnas Tour (with Cozido) ,all private tours include transfers and English Speaking Guide. Airfare included from Boston to Terceira, return from Sao Miguel to Boston as well as internal flights within the Azores. Includes Round-Trip Transfer from New Bedford to Boston Logan Airport. 761 Bedford Street, Fall River, MA 02723 www.sagresvacations.com Ph#508-679-0053 Your Itinerary Includes Hotels Angra do Heroismo, Terceira Island o Angra Garden Hotel Check in 12OCT-14OCT o Double Room with breakfast daily Horta, Faial Island o Faial Resort Hotel Check in 14OCT-16OCT o Double room with breakfast daily Ponta Delgada, Sao Miguel Island o Royal Garden Hotel Check in 16OCT-21OCT Double Room with breakfast daily Private Transfers Airport Transfers Included o New Bedford to Boston Logan Airport transfers round-trip 11OCT-21 OCT o TER Airport to Angra Garden Hotel and vice-versa 12OCT-14OCT o Horta Airport to Faial Resort Hotel and vice-versa 14OCT-16OCT. o P. Delgada Airport to Royal Garden Hotel and vice-versa Terceira 16OCT-21OCT. All Transfers included on Private Tours Private Tours/Excursions Terceira o Full Day Terceira Tour with Lunch. Faial o Full Day Faial Tour with Lunch o Pico -

Vulnerability of Water Bodies to Diffuse Pollution in Small Islands: the Swiss Midland Lakes

COST Action 869, Working Group 4: Evaluation of projects in example areas: Vulnerability of water bodies to diffuse pollution in small islands: The Swiss Midland Lakes. June 24 - 26, 2009, Nottwil (CH) a hydrological perspective Action 869 M.I.P. de Lima (1,2) and J.L.M.P. de Lima (1,3) (1) Institute of Marine Research, (2) Forestry Dep., ESAC/Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra, Portugal ([email protected]), (3) Dep. Civil Engineering, Univ. of Coimbra, Portugal ([email protected]) FCTUC Introduction Study area Eutrophication of water bodies, The Archipelago of Azores is located in the North Atlantic Ocean. This archipelago is included in the Macaronesian region together with Madeira resulting from anthropogenic activities, (Portugal), Canary (Spain) and Cape Verde archipelagos. The Azores archipelago is formed by 9 small islands, with areas ranging from 17 to 747 km2. is one of the most serious problems of These islands are of volcanic origin and are characterized by very steep landscapes. In general, orography is responsible for significant climatic degradation of their physical, chemical variations among and within the islands. The Azores is strongly influenced by its oceanic location; it is characterized by high precipitation and high and biological quality. The complexity humidity. Precipitation shows a prominent east-west gradient with substantially higher annual rainfall in the westerly islands. The freshwater (surface and of the processes involved includes the aquifers) systems in the Macaronesian islands are unique due to their volcanic origin and oceanic setting, catchment morphology, storage processes, strong effect caused by climatic, and the presence of distinct freshwater communities. -

Ponta Delgada . 07-08 Junho'2013 Livro De Actas

PONTA DELGADA . 07-08 JUNHO’2013 LIVRO DE ACTAS Comissão Científica Doutor José Manuel Viegas de Oliveira Neto Azevedo Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Biologia da Universidade dos Açores (UAc) Preside às Jornadas Doutora Gilberta Margarida de Medeiros Pavão Nunes Rocha Professora Catedrática do Departamento de História, Filosofia e C. Sociais da UAc Doutor Nelson José de Oliveira Simões Professor Catedrático do Departamento de Biologia da UAc Doutor Paulo Alexandre Vieira Borges Professor Auxiliar com Agregação do Departamento de Ciências Agrárias da UAc Doutor Ricardo da Piedade Abreu Serrão Santos Investigador Principal do Departamento de Oceanografia e Pescas da UAc Doutor Pedro Miguel Valente Mendes Raposeiro Bolseiro Pós-Doutorado do Departamento de Biologia da UAc Comissão Organizadora Dr. Fábio Vieira Adjunto do Sr. Secretário Regional da Educação, Ciência e Cultura Dr. João Gregório Diretor de Serviços do Serviço de Ciência da Secretaria Regional da Educação, Ciência e Cultura Mestre Francisco Pinto Vogal do Conselho Administrativo do Fundo Regional para a Ciência Dr.ª Antónia Ribeiro Técnica superior do Serviço de Ciência da Secretaria Regional da Educação, Ciência e Cultura Nota: A aplicação das normas do Acordo Ortográfico foi deixada ao critério de cada autor. 2 Índice Resumo, conclusões e Recomendações............................................................................................................9 01. ciências sociais e Humanidades.................................................................................................................. -

Tese 9366 Dissertação Lorena Baptista Almeida.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO ESPÍRITO SANTO CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS E NATURAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BIOLOGIA VEGETAL LORENA BAPTISTA ALMEIDA VARIAÇÃO ESPACIAL LONGITUDINAL DA COMUNIDADE FITOPLANCTÔNICA, ESTADO TRÓFICO E VARIÁVEIS AMBIENTAIS DE DUAS LAGOAS COSTEIRAS DO MUNICÍPIO DA SERRA/ES: LAGOA JUARA E LAGOA JACUNÉM. VITÓRIA 2015 LORENA BAPTISTA ALMEIDA VARIAÇÃO ESPACIAL LONGITUDINAL DA COMUNIDADE FITOPLANCTÔNICA, ESTADO TRÓFICO E VARIÁVEIS AMBIENTAIS DE DUAS LAGOAS COSTEIRAS DO MUNICÍPIO DA SERRA/ES: LAGOA JUARA E LAGOA JACUNÉM. Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós Graduação em Biologia Vegetal da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Biologia Vegetal, na área de concentração Fisiologia Vegetal. Orientadora: Valéria de Oliveira Fernandes VITÓRIA 2015 2 LORENA BAPTISTA ALMEIDA VARIAÇÃO ESPACIAL LONGITUDINAL DA COMUNIDADE FITOPLANCTÔNICA, ESTADO TRÓFICO E VARIÁVEIS AMBIENTAIS DE DUAS LAGOAS COSTEIRAS DO MUNICÍPIO DA SERRA/ES: LAGOA JUARA E LAGOA JACUNÉM. Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós Graduação em Biologia Vegetal da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Biologia Vegetal, na área de concentração Fisiologia Vegetal. COMISSÃO EXAMINADORA Prof. Dra. Valéria de Oliveira Fernandes Programa de Pós Graduação em Biologia Vegetal/UFES Orientadora Prof. Dr. Camilo Dias Junior Programa de Pós Graduação em Biologia Vegetal/UFES Membro Interno Prof. Dra. Marina Satika Suzuki Programa de Pós Graduação em Ecologia e Recursos Naturais/UENF Membro Externo 3 À DEUS, por seu amor incondicional. À minha família; Mãe, Pai e Renan, que sempre me apoiaram em tudo. Ao Rikim, por me entender e me amar. 4 AGRADECIMENTOS Foram dois anos intensos, de muita pesquisa e muito aprendizado.. -

GUIA SETE CIDADES CRESAÇOR – Azores for All

GUIA SETE CIDADES CRESAÇOR – Azores For All EDIÇÃO CRESAÇOR – Cooperativa Regional Economia Solidária CRL TEXTOS Dulce Pacheco, João Nunes, Maria Manuela Albergaria, Manuela Soeiro, Paulo Garcia REVISÃO DO TEXTO Manuela Soeiro, Michael Ross, Samanta Fontes FOTOGRAFIAS Azoresphotos (Associação Turismo dos Açores), CRESAÇOR, Direção Regional da Cultura, Eduardo Miranda, Nuno Fonseca, Paulo Garcia, SIARAM PROJETO GRÁFICO E PAGINAÇÃO CRESAÇOR – Criações Periféricas Elisabete Ross Índice 1 A Ilha de São Miguel 4 2 Contextualização Sócio-Histórica 6 3 Morfologia 12 4 Geologia 15 5 Flora e Fauna 19 6 Área de Paisagem Protegida 23 7 Trilhos 25 8 O que fazer – Atividades de Natureza 28 9 Código de Conduta 32 3 1 A Ilha de São Miguel São Miguel, a maior das nove da ilha, um processo que teve ilhas vulcânicas que constituem início na zona de Nordeste, o arquipélago dos Açores, tem há cerca de 4 milhões de anos. uma área de 745 km2, um com- A ilha ganhou a forma atual primento de 62 km e largura míni- com a união, nos últimos 50 ma de 8 km e máxima de 15 km. mil anos, do vulcão das Sete Tal como outras ilhas dos Cidades à restante ilha. Açores, a formação da ilha Em qualquer altura do ano de São Miguel deveu-se a diver- a ocorrência de nuvens e chuva sas fases e erupções vulcânicas, é frequente, o que permite a que foram aumentando a área manutenção de extensas áreas 4 1 A Ilha de São Miguel – Miradouro do Pico do Carvão verdes e contribui para a exube- A ilha de São Miguel conta com rância vegetal e valor paisagísti- 6 concelhos e 64 freguesias co das mesmas. -

Parthenogenetic /Schnura Hastata Revisited: Present Status and Notes on Population Ecology and Behaviour (Odonata: Coenagrionidae)

------------PhilipS. Corbet memorial issue----------- Parthenogenetic /schnura hastata revisited: present status and notes on population ecology and behaviour (Odonata: Coenagrionidae) 1 1 M. Olalla Lorenzo-Carballa , Christopher D. Beatty , Carlo UtzerP, 3 1 4 Virgilio Vieira & Adolfo Cordero-Rivera • 1Grupo de Ecoloxfa Evolutiva e da Conservaci6n, Universidade de Vigo, EUET Forestal, Campus Universitario, 36005 Pontevedra, Galiza, Spain. <olalla.lorenzo®uvigo.es>, <beattych®yahoo.com>, <adolfo.cordero®uvigo.es> 2Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e deii'Uomo, Viale deii'Universita 32, 00191 Roma, Italy. <carlo.utzeri®uniroma1.it> 3Departamento de Biologia e CIRN, Universidade dos Ac,;ores, Apartado 1422, 9501-801 Ponta Delgada, Ac,;ores, Portugal. <vvieira®uac.pt> 4Author for correspondence Key words: Odonata, dragonfly, lschnura hastata, parthenogenesis, population size, survivorship, fertility, underwater oviposition, water quality, Azores archipelago. ABSTRACT Populations of Ischnura hastata found in the Azores archipelago represent the only known example of parthenogenesis in the order Odonata. In this paper, we present results from fieldwork done on the islands of Sao Miguel, Pico, Santa Maria, and Graciosa, aimed at characterizing population ecology and habitat preferences of this species. Sampling of several ponds in the islands of Sao Miguel and Pico showed that I. hastata occurred in oligotrophic ponds, but was absent from all eutrophic ponds sampled, many of which have been impacted by cattle grazing and water ex traction by humans. This suggests that parthenogenetic populations are highly sen sitive to eutrophication, which may be different from suggested habitat preferences of sexual populations for this species. Mark-recapture studies showed I. hastata to occur in high densities in the studied populations. -

Matérias-Primas Naturais No Fabrico De Nanomateriais Mariana Santos

Matérias-Primas Naturais no Fabrico de Nanomateriais Mariana Santos Costa Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Engenharia Química Orientadores: Profª. Maria Clara Henriques Baptista Gonçalves Profª. Helena Cristina de Sousa Menezes Vasconcelos Júri Presidente: Prof. António Luís Vieira de Andrade Maçanita, IST-UL Orientador: Profª. Maria Clara Henriques Baptista Gonçalves, IST-UL Vogal: Profª. Isabel Maria de Figueiredo Ligeiro da Fonseca, FCT-UNL Novembro de 2017 A mente que se abre a uma nova ideia nunca mais volta ao seu tamanho original. Albert Einstein ii Agradecimentos Queria deixar os meus sinceros agradecimentos a todos aqueles que colaboraram e contribuíram para a realização da minha tese de Mestrado: À minha orientadora, Profª. Maria Clara Gonçalves, do IST, obrigada pela oportunidade de realizar este trabalho, por todo o apoio e incentivo e pelas sugestões dadas durante a tese. À minha coorientadora, Profª. Cristina Vasconcelos, obrigada pela ajuda e apoio prestados durante a minha visita à Universidade dos Açores. Obrigada, também, Paulo e Afonso. Agradeço por me terem feito sentir em casa e por fazerem com que a experiência nos Açores fosse fantástica! Um grande obrigado à Joana Matos, por todas as explicações ao longo do trabalho experimental e pela ajuda no laboratório! Obrigada também ao Prof. Vítor Gonçalves e ao Telmo Eleutério, da Universidade dos Açores, que me deram os conhecimentos e o incentivo necessários para o arranque do trabalho. A caracterização das amostras não seria possível sem a Engª. Isabel Nogueira, a Profª. Maria João Ferreira, o Prof. Auguste Fernandes, o Prof. António Maurício, o Profº. Manuel Francisco Pereira, a Profª. -

Plano Da Bacia Hidrográfica Da Lagoa Das Sete Cidades (Açores) Compatibilização Entre Sistema Produtivo E Ambiente1

Plano da Bacia Hidrográfica da Lagoa das Sete Cidades (Açores) Compatibilização entre sistema produtivo e ambiente1 João PORTEIRO2 Helena CALADO2 Secção de Geografia do Departamento de Biologia Universidade dos Açores Rua Mãe de Deus, Apartado 1422, 9501-801 PONTA DELGADA (PORTUGAL) Tel.: +351.296650479 Fax: +351.296650100 e-mail: [email protected] Margarida PEREIRA2 e-Geo – Centro de Estudos de Geografia e Planeamento Regional Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa Avenida de Berna, 26-C, 1069-061 LISBOA (PORTUGAL) Tel.: +351.217933519 Fax: +351.217977759 e-mail: ma.pereira @fcsh.unl.pt Resumo A eutrofização das lagoas dos Açores é um grave problema ambiental da região, indissociável do sistema produtivo ancorado na agro-pecuária com fins industriais (fileira do leite). As características físicas do território (climáticas, geomorfológicas e hidrológicas), aliadas às condições de desenvolvimento daquela actividade (ruptura com os métodos de produção tradicionais, alargamento das pastagens para parcelas sem aptidão, arroteamento da floresta endémica, incremento do encabeçamento e aplicação excessiva de fertilizantes inorgânicos) provocaram uma carga excessiva de nutrientes nos planos de água e os ecossistemas demonstraram incapacidade de regeneração. As medidas minimizadoras para debelar as consequências, desencadeadas pela Administração, não se revelaram promissoras. Em 1998, a Universidade dos Açores defende o Plano de Ordenamento da Bacia Hidrográfica das Setes Cidades como estratégia de actuação. -

Natural Landscapes & Gardens of Madeira & the Azores 2021

Natural Landscapes & Gardens of Madeira & the Azores 2021 29 MAY – 16 JUN 2021 Code: 22117 Tour Leaders John Patrick, Dr Gerald Luckhurst Physical Ratings Explore the natural landscapes and gardens of Madeira and the Azores including São Miguel, Flores, Terceira, Pico and Faial islands. Overview Led by John Patrick, horticulturalist, garden designer and former presenter on ABC TV’s Gardening Australia, explore the natural flora and fauna of Madeira and Azores. In Madeira John will be joined by landscape architect, Gerald Luckhurst, who has designed and built many gardens on the island. He is an expert plantsman with an unrivalled knowledge of sub-tropical flora an author of the book The Gardens of Madeira. The program includes six moderate nature walks ranging in length from 1.3 to 7.7kms. Visit subtropical Madeira and five volcanic islands from the three geographical groups of the Azores: São Miguel (Eastern Group), Terceira, Faial & Pico (Central Group) & Flores (Western Group). Spend 6 nights based in Funchal, the capital of Madeira; overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, the city is framed by a dramatic backdrop of cloud-tipped mountains and features a wealth of historic monuments. Explore Madeira's abundance of colourful and exotic flora in its parks and gardens including the Quinta do Palheiro and Monte Palace Tropical Gardens; walk some of Madeira's scenic levada (man- made irrigation channels); and view the Laurisilva of Madeira, the largest surviving area of laurel forest containing a unique suite of flora and fauna including many endemic species. Meet Raimundo Quintal, Madeira's leading environmentalist and author of numerous books including the Levadas and Footpaths of Madeira; we visit the Santo da Serra Environmental Education Camp where to learn about the conservation and recovery of the native Laurisilva forest. -

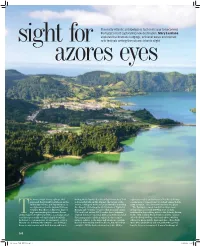

The Misty Atlantic Archipelago Is Fast on Its Way to Becoming Portugal's

The misty Atlantic archipelago is fast on its way to becoming Portugal’s most captivating new destination. Mary Lussiana explores the dramatic lodgings, artisanal wines and vibrant sight for arts festivals setting the volcanic islands alight azores eyes he Azores High. It was a phrase that In May, Delta launched a direct flight from New York night after night, and to have fuelled the delicious peppered the British broadsheets in the to Ponta Delgada on São Miguel, the largest of the renaissance of wines from Pico Island: mineral-rich, sultry days of June and July this year, as Azores, adding yet more access and further denuding salty, complex – the Azores themselves in a glass. an explanation for the unusually warm the duopoly (following the 2015 launch of flights by The Portuguese made landfall on this remote weather. But there’s a different kind of Ryanair and – briefly – easyJet) that national carrier archipelago, scattered 1,300km west of their high surrounding the Atlantic Ocean TAP and local airline SATA used to have. Intimate, mainland in the swirling mists of the Atlantic Ocean, Tarchipelago itself right now, with a sea change afoot original hotels are opening, with a sophisticated and in the 15th century. They christened it the Açores, across its spectacular volcanic islands. Festivals discerning market in their sights. It’s as yet in its after the birds circling ceaselessly above. History dedicated to contemporary art and music – plus a infancy, relative to the mass and adventure tourism relates far more quietly their mistake – those birds literary one debuting this autumn – are driving a that has historically dominated here, but still robust were kites (milhafres) and not goshawks (açores) – boom in arts tourism with both brains and heart. -

Dados Preliminares Sobre O Estado Trófico Da Lagoa Das Sete Cidades

DADOS PRELIMINARES SOBRE O ESTADO TRÓFICO DA LAGOA DAS SETE CIDADES Por J. MEDEIROS, G. FLORES e F. RIBEIRO Laboratório de Ecologia Aplicada Secção de Quúnica Univ. dos Açores, 9500 Ponta Delgada Urna vez que nos últimos tempos se têm notado vários índi- ces de eutrofização nas Lagoas de S. Miguel, foi iniciado um trabalho sob o ponto de vista químico com o fim de caracte- rizar as mesmas. Esse estudo foi começado na Lagoa das Sete Cidades havendo já alguns parâ~metrosdeterminados. Foi localizada a principal fonte de poluição das Lagoas -na vila das Sete Cidades - assim como, uma desoxigenação acentuada nestas Lagoas monomícticas no Verão e Outono. SUMMARY Signs of eutrophication have been noticed recently on the lakes of São Miguel, Azores. Our work started with the caracterization of the Sete Ci- dades lake, using severa1 chemical parameters. !@hemain J. MBDEIROS, G. FLORES e F. RIBBIRO source of pollution was determined to be located on the village of Sete Cidades. A drop in oxygen was noticed in these mono- rnictic lakes during Summer and Autumn. Todos os lagos estão sujeitos a um processo de envellieci- mento natural no qual a acumulação gradual de detritos e de matéria orgânica provoca a transformação do lago em pântano. Os lagos jovens (oligotróficos) apresentam baixas concen- trações em nutrientes, produtividades de vegetação aquática superior muito pequenas, águas claras, frias e oxigenadas até ao fundo (PESSON, 1976). Estes lagos adquirem, a partir das suas bacias de drenagem, lodo, minerais e outros nutrientes, tais como, fósforo e azoto. Este aumento em nutrientes origina um aumento na produtivi- dade biológica.