Depression: This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print Your Symptom Diary

MEDICATION GUIDE FETZIMA® (fet-ZEE-muh) (levomilnacipran) extended-release capsules, for oral use What is the most important information I should know about FETZIMA? FETZIMA may cause serious side effects, including: • Increased risk of suicidal thoughts or actions in some children, adolescents, and young adults. FETZIMA and other antidepressant medicines may increase suicidal thoughts or actions in some children and young adults, especially within the first few months of treatment or when the dose is changed. FETZIMA is not for use in children. o Depression or other serious mental illnesses are the most important causes of suicidal thoughts or actions. Some people may have a higher risk of having suicidal thoughts or actions. These include people who have (or have a family history of) depression, bipolar illness (also called manic-depressive illness) or have a history of suicidal thoughts or actions. How can I watch for and try to prevent suicidal thoughts and actions? o Pay close attention to any changes, especially sudden changes in mood, behavior, thoughts, or feelings, or if you develop suicidal thoughts or actions. This is very important when an antidepressant medicine is started or when the dose is changed. o Call your healthcare provider right away to report new or sudden changes in mood, behavior, thoughts, or feelings. o Keep all follow-up visits with your healthcare provider as scheduled. Call your healthcare provider between visits as needed, especially if you have concerns about symptoms. Call your healthcare provider or -

Levomilnacipran (Fetzima®) Indication

Levomilnacipran (Fetzima®) Indication: Indicated for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD), FDA approved July 2013. Mechanism of action Levomilnacipran, the more active enantiomer of racemic milnacipran, is a selective SNRI with greater potency for inhibition of norepinephrine relative to serotonin reuptake Compared with duloxetine or venlafaxine, levomilnacipran has over 10-fold higher selectivity for norepinephrine relative to serotonin reuptake inhibition The exact mechanism of the antidepressant action of levomilnacipran is unknown Dosage and administration Initial: 20 mg once daily for 2 days and then increased to 40 mg once daily. The dosage can be increased by increments of 40 mg at intervals of two or more days Maintenance: 40-120 mg once daily with or without food. Fetzima should be swallowed whole (capsule should not be opened or crushed) Levomilnacipran and its metabolites are eliminated primarily by renal excretion o Renal impairment Dosing: Clcr 30-59 mL/minute: 80 mg once daily Clcr 15-29 mL/minute: 40 mg once daily End-stage renal disease (ESRD): Not recommended Discontinuing treatment: Gradually taper dose, if intolerable withdrawal symptoms occur, consider resuming the previous dose and/or decrease dose at a more gradual rate How supplied: Capsule ER 24 Hour Fetzima Titration: 20 & 40 mg (28 ea) Fetzima: 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg, 120 mg Warnings and Precautions Elevated Blood Pressure and Heart Rate: measure heart rate and blood pressure prior to initiating treatment and periodically throughout treatment Narrow-angle glaucoma: may cause mydriasis. Use caution in patients with controlled narrow- angle glaucoma Urinary hesitancy or retention: advise patient to report symptoms of urinary difficulty Discontinuation Syndrome Seizure disorders: Use caution with a previous seizure disorder (not systematically evaluated) Risk of Serotonin syndrome when taken alone or co-administered with other serotonergic agents (including triptans, tricyclics, fentanyl, lithium, tramadol, tryptophan, buspirone, and St. -

Levomilnacipran for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder

Out of the Pipeline Levomilnacipran for the treatment of major depressive disorder Matthew Macaluso, DO, Hala Kazanchi, MD, and Vikram Malhotra, MD An SNRI with n July 2013, the FDA approved levomil- Table 1 once-daily dosing, nacipran for the treatment of major de- Levomilnacipran: Fast facts levomilnacipran pressive disorder (MDD) in adults.1 It is I Brand name: Fetzima decreased core available in a once-daily, extended-release formulation (Table 1).1 The drug is the fifth Class: Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake symptoms of inhibitor serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibi- MDD and was well Indication: Treatment of major depressive tor (SNRI) to be sold in the United States disorder in adults tolerated in clinical and the fourth to receive FDA approval for FDA approval date: July 26, 2013 trials treating MDD. Availability date: Fourth quarter of 2013 Levomilnacipran is believed to be the Manufacturer: Forest Pharmaceuticals more active enantiomer of milnacipran, Dosage forms: Extended–release capsules in which has been available in Europe for 20 mg, 40 mg, 80 mg, and 120 mg strengths years and was approved by the FDA in Recommended dosage: 40 mg to 120 mg 2009 for treating fibromyalgia. Efficacy of capsule once daily with or without food levomilnacipran for treating patients with Source: Reference 1 MDD was established in three 8-week ran- domized controlled trials (RCTs).1 cial and occupational functioning in addi- Clinical implications tion to improvement in the core symptoms Levomilnacipran is indicated for treating of depression.5 -

Premium Non-Specialty Quantity Limit List January 2016

Premium Non-Specialty Quantity Limit List January 2016 Therapeutic Category Drug Name Dispensing Limit Anti-infectives Antibiotics DIFICID (fidaxomicin) 200 mg 2 tabs/day & 10 days/30 days SIVEXTRO (tedizolid) Solr 6 vials/30 days SIVEXTRO (tedizolid) Tabs 6 tabs/30 days ZYVOX (linezolid) 28 tabs/30 days ZYVOX (linezolid) Suspension 4 bottles (600 mL)/28 days Antifungals LAMISIL (terbinafine) 250 mg 84 days supply/180 days Antimalarial QUALAQUIN (quinine) QL varies* Antivirals, Herpetic FAMVIR (famciclovir) 125 mg 1 tab/day FAMVIR (famciclovir) 250 mg 2 tabs/day FAMVIR (famciclovir) 500 mg 21 tabs/30 days SITAVIG (acyclovir) 50 mg 2 tabs/30 days VALTREX (valacyclovir) 1000 mg 3 tabs/day VALTREX (valacyclovir) 500 mg 2 tabs/day Antivirals, Influenza RELENZA (zanamivir) QL is 40 inh per 365 days. TAMIFLU (oseltamivir) 30 mg 40 caps per 365 days TAMIFLU (oseltamivir) 45 mg, 75 mg 20 caps per 365 days TAMIFLU (oseltamivir) Suspension 360 mL/365 days Cardiology Anticoagulants ELIQUIS (apixiban) 2 tabs/day ELIQUIS (apixiban) 5 mg 3 tabs/day IPRIVASK (desirudin) 35 days supply/180 days PRADAXA (dabigatran) 2 caps/day SAVAYSA (edoxaban) 1 tab/day XARELTO (rivaroxaban) 10 mg 35 days supply/180 days XARELTO (rivaroxaban) 15 mg 2 tabs/day XARELTO (rivaroxaban) 20 mg 1 tab/day XARELTO (rivaroxaban) Starter Pack 2 starter packs/year Heart Failure CORLANOR (ivabradine) 2 tabs/day Central Nervous System ADHD Agents ADDERALL (amphetamine/dextroamphetamine) 3 tabs/day ADDERALL XR (amphetamine/dextroamphetamine mixed salts) 1 cap/day APTENSIO XR (methylphenidate) -

Pristiq (Desvenlafaxine Succinate) – First-Time Generic

Pristiq® (desvenlafaxine succinate) – First-time generic • On March 1, 2017, Teva launched AB-rated generic versions of Pfizer’s Pristiq (desvenlafaxine succinate) 25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg extended-release tablets for the treatment of major depressive disorder. — Teva launched the 25 mg tablet with 180-day exclusivity. — In addition, Alembic/Breckenridge, Mylan, and West-Ward have launched AB-rated generic versions of Pristiq 50 mg and 100 mg extended-release tablets. — Greenstone’s launch plans for authorized generic versions of Pristiq 25 mg, 50 mg, and 100 mg tablets are pending. — Lupin and Sandoz received FDA approval of AB-rated generic versions of Pristiq 50 mg and 100 mg tablets on June 29, 2015. Lupin’s and Sandoz’s launch plans are pending. • Other serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder include desvenlafaxine fumarate, duloxetine, Fetzima™ (levomilnacipran), Khedezla™ (desvenlafaxine) , venlafaxine, and venlafaxine extended-release. • Pristiq and the other serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors carry a boxed warning for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. • According to IMS Health data, the U.S. sales of Pristiq were approximately $883 million for the 12 months ending on December 31, 2016. optumrx.com OptumRx® specializes in the delivery, clinical management and affordability of prescription medications and consumer health products. We are an Optum® company — a leading provider of integrated health services. Learn more at optum.com. All Optum® trademarks and logos are owned by Optum, Inc. All other brand or product names are trademarks or registered marks of their respective owners. This document contains information that is considered proprietary to OptumRx and should not be reproduced without the express written consent of OptumRx. -

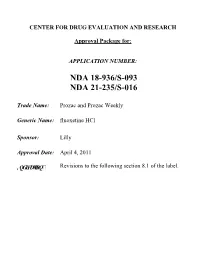

Prozac and Prozac Weekly (Fluoxetine Hcl)

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH Approval Package for: APPLICATION NUMBER: NDA 18-936/S-093 NDA 21-235/S-016 Trade Name: Prozac and Prozac Weekly Generic Name: fluoxetine HCl Sponsor: Lilly Approval Date: April 4, 2011 ,QGLFDWLRQ Revisions to the following section 8.1 of the label. CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: NDA 18-936/S-093 NDA 21-235/S-016 CONTENTS Reviews / Information Included in this NDA Review. Approval Letter X Other Action Letters X Labeling Summary Review X Officer/Employee List Office Director Memo Cross Discipline Team Leader Review Medical Review(s) X Chemistry Review(s) Pharmacology Review(s) Statistical Review(s) Clinical Pharmacology/Biopharmaceutics Review(s) Other Reviews X Proprietary Name Review(s) Administrative/Correspondence Document(s) X CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: NDA 18-936/S-093 NDA 21-235/S-016 APPROVAL LETTER DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Food and Drug Administration Silver Spring MD 20993 NDA 018936/S-091/S-093/S-095 NDA 021235/S-015/S-016/S-017 SUPPLEMENT APPROVAL Eli Lilly & Company Attention: Kevin C. Sheehan, MS, Pharm.D. Manager, Global Regulatory Affairs - US Lilly Corporate Center Indianapolis, IN 46285 Dear Dr. Sheehan: Please refer to your Supplemental New Drug Applications (sNDA) dated and received May 21, 2009 (018936/S-091 and 021235/S-015), November 6, 2009 (018936/S-093 and 021235/S-016), and April 14, 2010 (018936/S-095 and 021235/S-017), submitted under section 505(b) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) for Prozac (fluoxetine hydrochloride) 10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg capsules and Prozac Weekly (fluoxetine hydrochloride) 90 mg delayed-release capsules. -

Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014

Federal Bureau of Prisons Management of Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Practice Guidelines May 2014 Table of Contents 1. Purpose ............................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Natural History ................................................................................................................................. 2 Special Considerations ...................................................................................................................... 2 3. Screening ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Screening Questions .......................................................................................................................... 3 Further Screening Methods................................................................................................................ 4 4. Diagnosis ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Depression: Three Levels of Severity ............................................................................................... 4 Clinical Interview and Documentation of Risk Assessment............................................................... -

A Brief Overview of Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy

A Brief Overview of Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy Joel V. Oberstar, M.D. Chief Executive Officer Disclosures • Some medications discussed are not approved by the FDA for use in the population discussed/described. • Some medications discussed are not approved by the FDA for use in the manner discussed/described. • Co-Owner: – PrairieCare and PrairieCare Medical Group – Catch LLC Disclaimer The contents of this handout are for informational purposes only and are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical or psychiatric condition. Never disregard professional/medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this handout. Material in this handout may be copyrighted by the author or by third parties; reasonable efforts have been made to give attribution where appropriate. Caveat Regarding the Role of Medication… Neuroscience Overview Mind Over Matter, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. Available at: http://teens.drugabuse.gov/mom/index.asp. http://medicineworld.org/images/news-blogs/brain-700997.jpg Neuroscience Overview Mind Over Matter, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. Available at: http://teens.drugabuse.gov/mom/index.asp. Neurotransmitter Receptor Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse Common Diagnoses and Associated Medications • Psychotic Disorders – Antipsychotics • Bipolar Disorders – Mood Stabilizers, Antipsychotics, & Antidepressants • Depressive Disorders – Antidepressants • Anxiety Disorders – Antidepressants & Anxiolytics • Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – Stimulants, Antidepressants, 2-Adrenergic Agents, & Strattera Classes of Medications • Anti-depressants • Stimulants and non-stimulant alternatives • Anti-psychotics (a.k.a. -

Q 2: How Long Should Treatment with Antidepressants Continue in Adults with Depressive Episode/Disorder?

Duration of antidepressant treatment Q 2: How long should treatment with antidepressants continue in adults with depressive episode/disorder? Background Short-term therapy with antidepressant medication is considered standard treatment for acute treatment of moderate to severe depressive episode/disorder. However, because of the long-term nature of depressive disorders, with many patients at substantial risk of later recurrence, there is a need to establish how long, in general, such patients should stay on antidepressants if they have responded to the treatment. Population/Intervention(s)/Comparison/Outcome(s) (PICO) Population: individuals with depressive episode/disorder Interventions: antidepressant medications: tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) and related, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) Comparison: placebo Outcomes: o treatment effectiveness in terms of reduction symptoms o treatment effectiveness in terms of improvement in functioning o acceptability profile List of the systematic reviews identified by the search process INCLUDED IN GRADE TABLES OR FOOTNOTES Deshauer D et al (2008). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for unipolar depression: a systematic review of classic long-term randomized controlled trials. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178:293-1301. 1 Duration of antidepressant treatment Geddes JR et al (2003). Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet, 361:653-61. Hansen R et al (2008). Meta-analysis of major depressive disorder relapse and recurrence with second-generation antidepressants. Psychiatric Services, 59:1121-30. Kaymaz N et al (2008). Evidence that patients with single versus recurrent depressive episodes are differentially sensitive to treatment discontinuation: a meta- analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69:1423-36. -

Drug Repurposing for the Management of Depression: Where Do We Stand Currently?

life Review Drug Repurposing for the Management of Depression: Where Do We Stand Currently? Hosna Mohammad Sadeghi 1,†, Ida Adeli 1,† , Taraneh Mousavi 1,2, Marzieh Daniali 1,2, Shekoufeh Nikfar 3,4,5 and Mohammad Abdollahi 1,2,* 1 Toxicology and Diseases Group (TDG), Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center (PSRC), The Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (TIPS), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran; [email protected] (H.M.S.); [email protected] (I.A.); [email protected] (T.M.); [email protected] (M.D.) 2 Department of Toxicology and Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran 3 Personalized Medicine Research Center, Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran; [email protected] 4 Pharmaceutical Sciences Research Center (PSRC) and the Pharmaceutical Management and Economics Research Center (PMERC), Evidence-Based Evaluation of Cost-Effectiveness and Clinical Outcomes Group, The Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (TIPS), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran 5 Department of Pharmacoeconomics and Pharmaceutical Administration, School of Pharmacy, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran 1417614411, Iran * Correspondence: [email protected] † Equally contributed as first authors. Citation: Mohammad Sadeghi, H.; Abstract: A slow rate of new drug discovery and higher costs of new drug development attracted Adeli, I.; Mousavi, T.; Daniali, M.; the attention of scientists and physicians for the repurposing and repositioning of old medications. Nikfar, S.; Abdollahi, M. Drug Experimental studies and off-label use of drugs have helped drive data for further studies of ap- Repurposing for the Management of proving these medications. -

Levomilnacipran (Fetzima) for Major Depressive Disorder SAMIRA ZAMAN, MD, and MAURA R

STEPS New Drug Reviews Levomilnacipran (Fetzima) for Major Depressive Disorder SAMIRA ZAMAN, MD, and MAURA R. MCLAUGHLIN, MD, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, Virginia STEPS new drug reviews Levomilnacipran (Fetzima) is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) labeled cover Safety, Tolerability, for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults.1 Effectiveness, Price, and Simplicity. Each indepen- dent review is provided by authors who have no Drug Dosage Dose form Cost* financial association with Levomilnacipran 20 mg per day for two days, 20-, 40-, 80-, $286 for 30 capsules (prices the drug manufacturer. (Fetzima) then increases to 40 mg and 120-mg are identical for 20-,40-, This series is coordinated per day (maximum = 120 capsules 80-, and 120-mg capsules) by Allen F. Shaughnessy, mg per day) PharmD, MMedEd, Con- tributing Editor. *—Estimated retail price of one month’s treatment based on information obtained at http://www.goodrx.com (accessed August 19, 2015). A collection of STEPS pub- lished in AFP is available at http://www.aafp.org/ afp/steps. SAFETY when used concurrently with a cytochrome Levomilnacipran causes few serious adverse P450 3A4 inhibitor because levomilnaci- effects, although long-term safety has not pran is partially metabolized by the liver, been established.2 As with all antidepres- and medications that inhibit the cytochrome sants, levomilnacipran carries a warning P450 3A4 system, such as ketoconazole, may of increased risk of suicidal thoughts and cause it to accumulate.1 Patients with moder- behavior in patients 24 years or younger, and ate and severe renal impairment should be it has not been studied in patients younger limited to a dosage of 80 mg per day and 40 than 18 years.1 Levomilnacipran increases mg per day, respectively. -

Effects of Anti Depressants on Our Sleep

Effects of Anti Depressants on our sleep There still seems to be a lot of misunderstanding about all different kinds of Anti Depressants and what they do to our sleep. When to take them and especially the consequences for narcoleptics. Let’s start with naming them. 1. TCA - Tricyclic antidepressants Chemical compounds primarily used as antidepressant, first discovered in 1950. Have been largely replaced in clinical use in most parts of the world by newer antidepressants such as SSRI. Amitriptyline, Butriptyline, Clomipramine, Desipramine, Dosulepin, Doxepin, Imipramine, Iprindole, Lofepramine, Nortriptyline, Protriptyline, Trimipramine. 2. SSRI - Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor A class of drugs that are typically used as antidepressant in the treatment of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. Citalopram, Escitalopram, Fluoxetine, Fluvoxamine, Paroxetine, Sertraline. 3. SNRI – Serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors A class of antidepressant drugs used in the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) and other mood disorders. Sometimes also for anxiety disorders, OCD, ADHD, chronic neuropathic pain, and fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), and for the relief of menopausal symptoms. Venlafaxine (Effexor), Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq), Duloxetine (Cymbalta, Yentreve), Milnacipran (Dalcipran, Ixel, Savella), Levomilnacipran (Fetzima), Sibutramine (Meridia, Reductil) 4. SARI - Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor A class of drugs used mainly as antidepressants, but also as anxiolytics and hypnotics. Nefazodone (Serzone, Nefadar), Trazodone (Desyrel) 5. TeCA - Tetracyclic antidepressant A class of antidepressants introduced in the 1970s that are closely related to the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Most used is Mirtazapine Maprotiline (Deprilept, Ludiomil, Psymion), Mianserin (Bolvidon, Norval, Tolvon) Mirtazapine (Remeron, Avanza, Zispin) This material is provided for educational purposes only and is not intended for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.