Aspen Skiing Co. Vs Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Travel to Aspen Highlands by Bus to Catch the Maroon Bells Shuttle

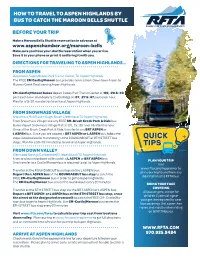

HOW TO TRAVEL TO ASPEN HIGHLANDS BY BUS TO CATCH THE MAROON BELLS SHUTTLE BEFORE YOUR TRIP Make a Maroon Bells Shuttle reservation in advance at www.aspenchamber.org/maroon-bells Make sure you have your shuttle reservation when you arrive. Save it to your phone or print it and bring it with you. DIRECTIONS FOR TRAVELING TO ASPEN HIGHLANDS... FROM ASPEN Downtown Aspen/Rubey Park Transit Center TO Aspen Highlands The FREE CM Castle/Maroon bus provides service from Downtown Aspen to Maroon Creek Road serving Aspen Highlands. CM-Castle/Maroon buses depart Rubey Park Transit Center at :00, :20 & :40 past each hour. And departs Castle Ridge at :07, :27 & :47 past each hour. Plan for a 15-20 minute trip to arrive at Aspen Highlands. FROM SNOWMASS VILLAGE Snowmass Mall/Base Village/ Brush Creek Road TO Aspen Highlands From Snowmass Village take any FREE SM-Brush Creek Park & Ride bus. Buses depart Snowmass Village Mall at :00, :15, :30 and :45 after the hour. Once at the Brush Creek Park & Ride, transfer to any BRT ASPEN or L ASPEN bus. Once you are aboard a BRT ASPEN or L ASPEN bus, follow the steps listed below for transferring at the ROUNDABOUT or 8TH STREET bus stops. Plan for a 30-40 minute trip to arrive at Aspen Highlands. FROM DOWN VALLEY Glenwood Springs/Carbondale/El Jebel/Basalt TO Aspen Highlands From any bus stop down valley catch a L ASPEN or BRT ASPEN bus. PLAN YOUR TRIP One transfer to a Castle/Maroon bus is required to get to Aspen Highlands. -

Colorado Ski Country Welcomes Improvements for the 2019-20 Winter Season

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Chris Linsmayer 303.866.9724 [email protected] Andy Stein 303-866-9712 [email protected] Colorado Ski Country Welcomes Improvements for the 2019-20 Winter Season Photos: TR – Purgatory Resort; TL – Powderhorn Mountain Resort BL – Steamboat Resort; BR – Purgatory Resort Click here for high res photos: http://bit.ly/WhatsNew2019-20 DENVER –September 4, 2019– Colorado Ski Country USA (CSCUSA) member ski areas have been busy this spring, summer and early fall working across the state on significant capital infrastructure improvements, new lodging options, dining experiences and more. In addition to improvements that seasoned skiers and riders will enjoy, CSCUSA members are also offering a wide variety of guest enhancements and learning options that brand-new skiers and riders or those returning the sport after some time away will be excited about this winter. Many will debut enhanced or remodeled rental shops including clothing rental options. Below is a summary of the many resort improvements at CSCUSA ski areas for the 2019-20 ski season. Opening and closing dates for the 2019-20 season are at the bottom of this release. Arapahoe Basin Ski Area After completing a 468-acre terrain expansion into the Beavers and the Steep Gullies last season, including the new four-person Beavers chairlift, A-Basin is continuing to upgrade its facilities. 2019-20 will be the first full season of Il Rifugo, the highest lift-served restaurant in North America at just over 12,500 feet serving charcuterie boards, wine, espresso and stunning views of the Continental Divide. A-Basin will also have newly remodeled bathrooms in the basement of the main lodge. -

Ski Resorts in the Western United States Ranked by Elevation (In Feet)

Ski Resorts in the Western United States Ranked by Elevation (in feet) Beginner(B) or Groomed Alternate Driving Time Driving Time Intermediate(I) Age Kids Top Cruising Base Lodging City Lodging (airport to (airport to Ski Resort Website State Location Lift Ticket Ski Free Elevation Rating** Elevation Elevation Lodging City Elevation Alternate Lodging City Closest Airport resort)*** Major airport resort)*** Arapahoe Basin http://www.arapahoebasin.com/ABasin/Default.aspx Colorado Dillon, CO 5- 13050 3 10780 9112 / 9035 Dillon/Silverthorne DEN-Denver 1:33 Loveland Ski Area http://www.skiloveland.com/ Colorado Georgetown, CO B 5- 13010 3 10800 9112 / 9035 Dillon/Silverthorne 5322 Denver DEN-Denver 1:19 Breckenridge http://www.breckenridge.com/ Colorado Breckenridge, CO 4- 12998 4 9600 9600 Breckenridge 9075 Frisco DEN-Denver 1:53 Telluride http://tellurideskiresort.com/TellSki/index.aspx Colorado Telluride, CO 12570 2 8725 8750 Telluride TEX-Telluride :14 MTJ-Montrose 1:29 Snowmass http://www.aspensnowmass.com/ Colorado Aspen, CO 12510 5 8104 9100 Snowmass Village 6171 Carbondale ASE-Aspen :18 DEN-Denver 3:43 Keystone http://www.keystoneresort.com/ Colorado Keystone, CO 4- 12408 4 9280 9173 Keystone Village 9075/9035/9112 Frisco/Silverthorne/Dillon EGE-Vail 1:18 DEN-Denver 1:42 Copper Mountain http://www.coppercolorado.com/winter/index.html Colorado Copper Mtn, CO 5- 12313 5 9712 9700 Copper Mountain 9075/9035/9112 Frisco/Silverthorne/Dillon EGE-Vail :49 DEN-Denver 1:39 Crested Butte http://www.skicb.com/cbmr/index.aspx Colorado Crested Butte, -

Aspen Snowmass 20-21 Chamber Letter

October 6, 2020 Dear Business Owner/Manager, As another ski season approaches, it is time to roll out our Chamber Pass Program for the 2020-21 season. As I am sure most of you have heard by now, we made some significant changes to our pass program this year. As you all know, this season will be like nothing we have seen before and it is going to take all of us working together to keep the season alive through April. The new Valley Weekday Pass offers great value for those with flexible schedules, and the Valley 7-Pack is the perfect option for the occasional skiers and riders. Combining those two products provides tremendous value and flexibility. The Chamber Premier Pass is also available, and for the second year, it includes a complimentary Ikon Base Pass. While our ticket offices remain open, we have introduced new technology to allow you to complete your Chamber Pass purchase without visiting a ticket office. Use this link to complete an online order form. Instructions for providing payment for online purchases are included on the order form. The attached guidelines should be helpful in planning your winter, but as always do not hesitate to go onto aspensnowmass.com for more information or to call us at 877-872- 7702. We appreciate your continued support of this discount program. WHAT’S HAPPENING AT ASPEN SNOWMASS New Big Burn Chairlift at Snowmass This summer, we replaced the Big Burn lift on Snowmass with a new six-passenger, high-speed chairlift as the old lift had reached its ‘operational lifetime. -

Aspen Skiing Company Operations Opening Plan Winter 2020/2021

Aspen Skiing Company Operations Opening Plan Winter 2020/2021 2020/2021 ASPEN SKIING COMPANY OPENING PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS COVID 19 State & County Guidelines Recommendations .................................................3 State Requirement Grid........................................................................................................4 Expected Operations ............................................................................................................6 Ability to Scale ....................................................................................................................6 Capacity ...............................................................................................................................7 Guest Communications Plan ................................................................................................8 LPHA collaboration .............................................................................................................8 Community Engagement .....................................................................................................9 Operations for On Mountain Divisions..............................................................................10 Mountain Operations o HVAC COVID19 Procedures ..........................................................10 o Product Sales & Services .................................................................12 o Parking & Shuttles ...........................................................................13 o Employee -

Aspen Skiing Co

At a time when other resorts were scaling back on major improvements, Aspen Skiing Aspen Skiing Co. Solutions for The RFID deployment is pervasive throughout ASC’s operations. People Access Access control is managed through the deployment of 43 SKIDATA Freemotion.Gate readers, 19 of which are Freemotion.Gate ‘Full’ Installation Date Autumn 2008 and to support high-traffic and volume locations. The RFID gates work Summer 2009 seamlessly with RFID media produced by the more than 200 Number of POS 225 RTP|ONE point-of-sale terminals. Through standard interfaces and Number of 114* (109 Coder SKIDATA Coders Unlimited 3S, 5 RTP|ONE Enterprise Architecture, scanning and sales across ASC’s Coding Units 1S) many lines of business are all managed in a single application. This POS Software RTP|ONE integration with RTP’s ticketing and POS software also enables ASC Access Software RTP|ONE to use the RFID media as a single form of ID and payment in its Access Gates 43 Freemotion (24 Freemotion.Gate retail and rental outlets, snowsports schools and other areas on ‘Open’/ 19 Freemotion. the mountain. Tying the media to a single customer record makes it Gate ‘Full’) easy for guests to make purchases throughout the group of resorts Readers* Data Carriers KeyCard Basic, without needing a credit card or cash. KeyCard Unlimited and TL 360 Special Features *Two phases. • Improves guest management and profitability through the support of multiple channels and improved security protection; reduces fraud • Provides cashless payment as RFID ticket and pass media are tied to a single customer record and can be used by guests throughout the resort for payments www.skidata.com. -

Aspen Winter Destination Guidethe St. Regis Aspen Resort

Welcome to our Mountainside Manor We are delighted that your winter travel plans include a stay at The St. Regis Aspen Resort. We will be more than happy to assist you with any activity or dinner reservations. If you plan on driving to Aspen, Independence Pass is closed for the Winter season. Please do not allow mapping software or guidance devices to lead you over this route from Denver. Arriving to The St. Regis Aspen Resort Aspen Pitkin County Airport (ASE) / Private 4 miles Eagle County egionalR Airport (EGE) 69 miles Grand Junction Regional Airport (GJT) 128 miles Denver International Airport (DEN) 222 miles The Ruby Park Transit Center (RFTA) 1 block Allow our St. Regis Airport Butler to provide guests with complimentary shuttle service to & from Aspen Pitkin County Airport and our resort. For a nominal fee, private aircraft and charters can also be met planeside. Round-trip service to/from alternative airports in Eagle, Grand Junction and Denver is also available at an additional cost. Other local transportation needs are happily coordinated by our concierge team. For guests arriving in their own vehicles, nightly valet parking is available for a nominal fee. 2 3 The St. Regis Aspen Resort | 315 East Dean Street, Aspen, Colorado 81611 | +1 970-920-3300 Winter Activities Skiing & Snowboarding Lift Tickets / Group Ski Lessons One lift ticket can be used at Aspen, Highlands, Buttermilk, and Snowmass Mountains. Advance reservations are not necessary but 7-day advance reservations can be purchased at a discount, when buying 2 or more days (holiday season not included). -

Skyhousoct2012.Pdf

I I a f ,ey/Alpine Meadows ft of heli-skiing. I midmountain at f:rhoe Resort, The Ritz- e Tahoe (ritzcarlton s 153guest roonls, uitesand The Ritz- I lhe ultraluxehotel I v packages,including juvenate You. Valid 1f.i l(r, it includesoven.right rrns,a 50-minute . lunch and an hour- rnessclass for two. llation Residencesat rn stel Iatio natnorths tar ta rr l-role-ownership .^ d\"{LLrI^.1: -^-,-. ru, 'rienitieswith, The :1.r..,' LakeTahoe. its l7 tirlly Furnishedtwo-, Lr-bedroomresidences ir r.acationrental or i.000 to $2.3 million). q l covetedaddress on -lcof I-ake T:rhoe, the :y Lake Tahoe Resort, no (laketahoe.hyatt.com) illion overhaulto irc 422 .st rooms and suites. SnowmassVillage, featuresroom upgrades;The Snowmass Kitchen MOUNTAINUPDATE restaur:rnt,witl-r seating for 233: and :reo a $300,000 facelift, Aspen Skiing Company's a first-classspa and fitnessfacilirr'. s lcgendary Olympic Thanksto like-clockworr< (aspensnowmass.com)$26 million The Little Nell (thelittlenell I reopenthis winter snowfalland morethan 300 investment in capital improvements .com), Aspen'sonly five-star,five- rscaletable-service days of sunshineper year, includes the new $7 million Tiehack diamond hotel offeringski-in/ski-out o the first Full season Coloradois home to some Express quad lift at Buttermilk. accessto Aspen Mountain, elevates rr Rocker@Squaw (a of the world's best-and Now the stand-infor the EagleHill winter stayswith the Ultimate Ski ,mfbrt-food-with-a- most reliable-skiing.Heavy and Upper Tiehack lifts, this high- Free package,featuring one full-dav Base Bar + K'Tchen dumps of pristinesnow at speedhoist also acts as a porthole to private lesson,pren-rium ski rentals, :ller apris-skiparty more than 20 ski resorts new gladed terrain for intermediate a pair oflift tickets per day (valid k oFOlvmpic House). -

2019 Building Permit Applications

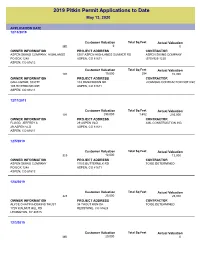

2019 Pitkin Permit Applications to Date May 13, 2020 APPLICATION DATE 12/13/2019 Customer Valuation Total Sq Feet Actual Valuation MS 0 0 OWNER INFORMATION PROJECT ADDRESS CONTRACTOR ASPEN SKIING COMPANY, HIGHLANDS 5307 ASPEN HIGHLANDS SUMMER RD ASPEN SKIING COMPANY PO BOX 1248 ASPEN, CO 81611 (970) 925-1220 ASPEN, CO 81612 Customer Valuation Total Sq Feet Actual Valuation 101 10,000 294 10,000 OWNER INFORMATION PROJECT ADDRESS CONTRACTOR GALLAGHER, SCOTT 103 RIVERDOWN DR LICENSED CONTRACTOR NOT REQUIRED 105 RIVERDOWN DR ASPEN, CO 81611 ASPEN, CO 81611 12/11/2019 Customer Valuation Total Sq Feet Actual Valuation 101 293,000 1,652 293,000 OWNER INFORMATION PROJECT ADDRESS CONTRACTOR FLOOD, JEFFREY A 29 ASPEN VLG AML CONSTRUCTION INC 29 ASPEN VLG ASPEN, CO 81611 ASPEN, CO 81611 12/5/2019 Customer Valuation Total Sq Feet Actual Valuation 329 12,000 12,000 OWNER INFORMATION PROJECT ADDRESS CONTRACTOR ASPEN SKIING COMPANY 115 E BUTTERMILK RD TO BE DETERMINED PO BOX 1248 ASPEN, CO 81611 ASPEN, CO 81612 12/4/2019 Customer Valuation Total Sq Feet Actual Valuation 328 25,000 25,000 OWNER INFORMATION PROJECT ADDRESS CONTRACTOR ALYCE CHAPIN HOSKINS TRUST 34 TROUT RUN DR TO BE DETERMINED 1725 WALNUT HILL RD REDSTONE, CO 81623 LEXINGTON, KY 40515 12/3/2019 Customer Valuation Total Sq Feet Actual Valuation MS 20,000 0 2019 Pitkin Permit Applications to Date May 13, 2020 APPLICATION DATE OWNER INFORMATION PROJECT ADDRESS CONTRACTOR ROARING FORK MEADOWS LLC 165 HOAGLUND RANCH RD ASPEN CONSTRUCTORS, INC 55 WAUGH DR #1111 BASALT, CO 81621 (970) 925-7608 -

Hardcopy by Case Name

CASELOAD INDEX 10-Jun-20 CASE NAME PARCEL ID # CASE NUMBER BOCC ACTION PZ ACTION PLAT RECORDED (BK PG) BOA80-34 BOA13-08 BOA13-07 BOA13-05 273707106002 P046-18 (Auster) Hummingbird Lode 1041 Hazar 273704200020 P001-95 021-1995 # (McCloskey) Hunter Creek Ranch Speci 273705300001 P67A-87 87-116 NR 0876 Snowmass Creek LLC GMQS Co 246734100004 P136-07 023-2008 #548222 #068-2 001-2008 #547951 n/a 0876 Snowmass Creek LLC Subdivision 246734100004 P102-09 077-2009 #564656 041-20 B94 P4-5 #541143 10 Maroon Drive LLC Activity Envelop 273503401001 P063-16 B116 P87-88 #634436 1033 Willoughby Way, LLC 1041 Haza 273501402006 P041-05 B72 P18 #507294 1099 Willoughby Way Partners LLC Ac 273501402002 P097-18 B125 P78 #657692 10th Mountain Hut Lenado Parking Lot 264127200028 P023-01 113-2001 #456384 12 Hours of Snowmass BBQ Temporary 246734401001 SP025-08 12 Hours of Snowmass BBQ Temporary 264323401001 SP023-09 1266 OCR LLC Activity Envelope and 264334300002 P094-18 need?? 1266 OCR LLC Front Yard Setback and 264334300002 BOA011-18 n/a 1266 OCR LLC Major Road Setback Va 264334300002 BOA013-17 n/a 1347 Red Mountain Road LLC Activity 273706304006 P081-12 1347 Red Mtn Rd. LLC (Israel) Minor 273706304006 P074-05 B74 P87 #513651 1355 Medicine Bow Road LLC Reinstat 264321305002 P057-10 Page 1 of 340 CASE NAME PARCEL ID # CASE NUMBER BOCC ACTION PZ ACTION PLAT RECORDED (BK PG) 13th Annual Bash for the Buddies 2012 264335404002 SP016-12 144 Magnifico LLC 1041 Hazard Revie 273501403018 P123-05 B74 P98 #514376 148 Placer Lane LLC Minor Amendmen 273707275002 P078-13 -

Aspen Mountain Ski Resorts by Lisa Marie Mercer, Demand Media

Aspen Mountain Ski Resorts by Lisa Marie Mercer, Demand Media The story of Aspen is a story of two dreams fulfilled. Friedl Pfeifer was a ski instructor who wanted to build a ski area in Aspen. Walter Paepcke was an industrialist who saw the town's potential as a mecca for cultural and intellectual pursuits. The men joined forces, and Aspen became a world class ski resort and center for the arts and culture. Aspen is actually a family of four resorts, which are accessed with one lift ticket. They function as a true family, sharing similar traits while displaying distinct differences in character and ambiance. Aspen Mountain The town of Aspen's commitment to opulence and elegance began in 1892, when the Macy department store magnate Jerome Wheeler built the luxurious Hotel Jerome and the extravagant Wheeler Opera House. The hotel continues to provide upscale accommodations, and the opera house is a thriving entertainment venue. Aspen Mountain is known for its steep terrain and lack of suitable beginner runs; but even if your skills are not up to par, the town itself is worth a visit. If you are over age 50 and want to conquer your fear of moguls, consider enrolling in one of Aspen's three or four-day "Bumps for Boomers" clinics. As of 2010, the three- day clinic costs $747, and a four-day clinic costs $996. Aspen/Snowmass P.O. Box 1248 Aspen, CO 81612 800-308-6935 aspensnowmass.com Snowmass Ski Resort Snowmass, thanks to its 25,000- square-foot Treehouse Kids' Adventure Center, is Aspen's most family-friendly resort. -

Pitkin County at a Glance

Pitkin County is on the Move. Please note these new locations during our 2-year construction project... 123 Emma Road | Suite 106 | Basalt, CO 81621 | www.pitkincounty.com PITKIN COUNTY AT A GLANCE GEOGRAPHY Covering 975 square miles, Pitkin County is located in the heart of the White River National Forest, surrounded by the spectacular peaks of the central Rocky Mountains. Pitkin County includes the communities of Aspen, Snowmass, Woody Creek, Old Snowmass, Meredith, Thomasville, Redstone and portions of the town of Basalt. DEMOGRAPHICS The total population of Pitkin County is 17,845 - an increase of 17% since 2000. The median age of residents is 43.4. The County is experiencing rapid increases in the population over the age of 65 with the number of persons over the age of 65 in 2045 expected to nearly double. The median household income of Pitkin County residents is $71,196, but the average wage per job is just $49,460 — 14% lower than the State average. Even though the County has been very prosperous over the past 40 years, there are still significant community sustainability concerns including the affordability of housing, healthcare, transportation and an aging workforce. ECONOMY Best known for its four world-class ski resorts — Aspen Mountain, Aspen Highlands, Buttermilk and Snowmass, tourism is the mainstay of the local economy with arts, cultural and recreational events providing a year-round attraction. TRANSPORTATION Highway 82 is the only major roadway in Pitkin County leading into and out of Aspen via I 70 at Glenwood Springs to the north and over 12,000 foot Independence Pass to the south.