Kayes and the Hassaniyya Speakers of Mali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

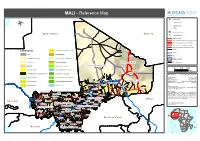

MALI - Reference Map

MALI - Reference Map !^ Capital of State !. Capital of region ® !( Capital of cercle ! Village o International airport M a u r ii t a n ii a A ll g e r ii a p Secondary airport Asphalted road Modern ground road, permanent practicability Vehicle track, permanent practicability Vehicle track, seasonal practicability Improved track, permanent practicability Tracks Landcover Open grassland with sparse shrubs Railway Cities Closed grassland Tesalit River (! Sandy desert and dunes Deciduous shrubland with sparse trees Region boundary Stony desert Deciduous woodland Region of Kidal State Boundary ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bare rock ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mosaic Forest / Savanna ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Region of Tombouctou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 100 200 Croplands (>50%) Swamp bushland and grassland !. Kidal Km Croplands with open woody vegetation Mosaic Forest / Croplands Map Doc Name: OCHA_RefMap_Draft_v9_111012 Irrigated croplands Submontane forest (900 -1500 m) Creation Date: 12 October 2011 Updated: -

The Question of 'Race' in the Pre-Colonial Southern Sahara

The Question of ‘Race’ in the Pre-colonial Southern Sahara BRUCE S. HALL One of the principle issues that divide people in the southern margins of the Sahara Desert is the issue of ‘race.’ Each of the countries that share this region, from Mauritania to Sudan, has experienced civil violence with racial overtones since achieving independence from colonial rule in the 1950s and 1960s. Today’s crisis in Western Sudan is only the latest example. However, very little academic attention has been paid to the issue of ‘race’ in the region, in large part because southern Saharan racial discourses do not correspond directly to the idea of ‘race’ in the West. For the outsider, local racial distinctions are often difficult to discern because somatic difference is not the only, and certainly not the most important, basis for racial identities. In this article, I focus on the development of pre-colonial ideas about ‘race’ in the Hodh, Azawad, and Niger Bend, which today are in Northern Mali and Western Mauritania. The article examines the evolving relationship between North and West Africans along this Sahelian borderland using the writings of Arab travellers, local chroniclers, as well as several specific documents that address the issue of the legitimacy of enslavement of different West African groups. Using primarily the Arabic writings of the Kunta, a politically ascendant Arab group in the area, the paper explores the extent to which discourses of ‘race’ served growing nomadic power. My argument is that during the nineteenth century, honorable lineages and genealogies came to play an increasingly important role as ideological buttresses to struggles for power amongst nomadic groups and in legitimising domination over sedentary communities. -

Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850

The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Benjamin, Jody A. 2016. The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493374 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 A dissertation presented by Jody A. Benjamin to The Department of African and African American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of African and African American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2016 © 2016 Jody A. Benjamin All rights reserved. Dissertation Adviser: Professor Emmanuel Akyeampong Jody A. Benjamin The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 Abstract This study re-examines historical change in western Africa during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through the lens of cotton textiles; that is by focusing on the production, exchange and consumption of cotton cloth, including the evolution of clothing practices, through which the region interacted with other parts of the world. It advances a recent scholarly emphasis to re-assert the centrality of African societies to the history of the early modern trade diasporas that shaped developments around the Atlantic Ocean. -

These Prevalence Du Vih Et Facteurs Associes Chez Les Professionnelles De Sexe Sur Le

Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la REPUBLIQUE DU MALI Un Peuple- Un But- Une Foi Recherche Scientifique UNIVERSITE DES SCIENCES, DES TECHNIQUES ET DES TECHNOLOGIES DE BAMAKO Faculté de Médecine et d’Odontostomatologie Année Universitaire : 2019-2020 N° : 21M….. THESE PREVALENCE DU VIH ET FACTEURS ASSOCIES CHEZ LES PROFESSIONNELLES DE SEXE SUR LE COMPLEXE MINIER LOULO/GOUNKOTO Présentée et soutenue publiquement le ……/……/2021 Devant le jury de la Faculté de Médecine et d’odontostomatologie par : Monsieur MOHAMED Ali Ag Souleymane Pour obtenir le grade de Docteur en Médecine (Diplôme d’état) Jury Président : Pr. Flabou BOUGOUDOGO Membres : Dr. Ibréhima Guindo Co-directreur : Dr. Abdoul A. SOW Directeur : Pr. Sounkalo DAO DEDICACES & REMERCIEMENTS PREVALENCE DU VIH ET FACTEURS ASSOCIES CHEZ LES PROFESSIONNELLES DE SEXE SUR LE COMPLEXE MINIER LOULO/GOUNKOTO DEDICACES ET REMERCIEMENTS A ALLAH Le Tout Puissant, Le Miséricordieux pour m’avoir donné la force et la santé de mener à bien ce travail. Au Prophète MOHAMAD (s a w) Grâce à qui je suis musulman et qui nous a exhorté vers le courage. A MON PERE Souleymane AG ALASSANE Autant de phrases et d’expressions aussi éloquentes soit elles ne sauraient exprimer ma gratitude et ma reconnaissance. Tu as su m’inculquer le sens de la responsabilité, de l’optimisme et de la confiance en soi face aux difficultés de la vie. Tes conseils ont toujours guidé mes pas vers la réussite. Ta patience sans fin, ta compréhension et ton encouragement sont pour moi le soutien indispensable que tu as toujours su m’apporter. -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

If Our Men Won't Fight, We Will"

“If our men won’t ourmen won’t “If This study is a gender based confl ict analysis of the armed con- fl ict in northern Mali. It consists of interviews with people in Mali, at both the national and local level. The overwhelming result is that its respondents are in unanimous agreement that the root fi causes of the violent confl ict in Mali are marginalization, discrimi- ght, wewill” nation and an absent government. A fact that has been exploited by the violent Islamists, through their provision of services such as health care and employment. Islamist groups have also gained support from local populations in situations of pervasive vio- lence, including sexual and gender-based violence, and they have offered to restore security in exchange for local support. Marginality serves as a place of resistance for many groups, also northern women since many of them have grievances that are linked to their limited access to public services and human rights. For these women, marginality is a site of resistance that moti- vates them to mobilise men to take up arms against an unwilling government. “If our men won’t fi ght, we will” A Gendered Analysis of the Armed Confl ict in Northern Mali Helené Lackenbauer, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Gabriella Ingerstad FOI-R--4121--SE ISSN1650-1942 November 2015 www.foi.se Helené Lackenbauer, Magdalena Tham Lindell and Gabriella Ingerstad "If our men won't fight, we will" A Gendered Analysis of the Armed Conflict in Northern Mali Bild/Cover: (Helené Lackenbauer) Titel ”If our men won’t fight, we will” Title “Om våra män inte vill strida gör vi det” Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--4121—SE Månad/Month November Utgivningsår/Year 2015 Antal sidor/Pages 77 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Utrikes- & Försvarsdepartementen Forskningsområde 8. -

Mli0006 Ref Region De Kayes A3 15092013

MALI - Région de Kayes: Carte de référence (Septembre 2013) Limite d'Etat Limite de Région MAURITANIE Gogui Sahel Limite de Cercle Diarrah Kremis Nioro Diaye Tougoune Yerere Kirane Coura Ranga Baniere Gory Kaniaga Limite de Commune Troungoumbe Koro GUIDIME Gavinane ! Karakoro Koussane NIORO Toya Guadiaba Diafounou Guedebine Diabigue .! Chef-lieu de Région Kadiel Diongaga ! Guetema Fanga Youri Marekhaffo YELIMANE Korera Kore ! Chef-lieu de Cercle Djelebou Konsiga Bema Diafounou Fassoudebe Soumpou Gory Simby CERCLES Sero Groumera Diamanou Sandare BAFOULABE Guidimakan Tafasirga Bangassi Marintoumania Tringa Dioumara Gory Koussata DIEMA Sony Gopela Lakamane Fegui Diangounte Goumera KAYES Somankidi Marena Camara DIEMA Kouniakary Diombougou ! Khouloum KENIEBA Kemene Dianguirde KOULIKORO Faleme KAYES Diakon Gomitradougou Tambo Same .!! Sansankide Colombine Dieoura Madiga Diomgoma Lambidou KITA Hawa Segala Sacko Dembaya Fatao NIORO Logo Sidibela Tomora Sefeto YELIMANE Diallan Nord Guemoukouraba Djougoun Cette carte a été réalisée selon le découpage Diamou Sadiola Kontela administratif du Mali à partir des données de la Dindenko Sefeto Direction Nationale des Collectivités Territoriales Ouest (DNCT) BAFOULABE Kourounnikoto CERCLE COMMUNE NOM CERCLE COMMUNE NOM ! BAFOULABE KITA BAFOULABE Bafoulabé BADIA Dafela Nom de la carte: Madina BAMAFELE Diokeli BENDOUGOUBA Bendougouba DIAKON Diakon BENKADI FOUNIA Founia Moriba MLI0006 REF REGION DE KAYES A3 15092013 DIALLAN Dialan BOUDOFO Boudofo Namala DIOKELI Diokeli BOUGARIBAYA Bougarybaya Date de création: -

Avis D'appel D'offres International

RÉPUBLIQUE DU MALI Un Peuple – Un But –Une Foi ----------------------- MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE ------------------------- SECRÉTARIAT GENERAL ------------------------- Agence d'Exécution des Travaux d'Infrastructures et d'Équipements Ruraux (AGETIER) Projet 1 du Programme de Renforcement de la Résilience a l’insécurité alimentaire et nutritionnelle au Sahel (P2RS) Travaux de construction de Micro Barrages, de surcreusement de Mares et d’aménagement de Bas-Fonds dans les cercles de Diéma et Nioro (Région de Kayes) ; Banamba, Kolokani et Nara (Région de Koulikoro) en cinq (05) lots AVIS D’APPEL D’OFFRES INTERNATIONAL Date : 06/03/2019 AOI N°: 04/ DG/AGETIER/ 2019 Micro barrages : Prêt FAD N° : 2100150032043 : 100% Mares : Protocole d’Accord de Don ° 2100155028523 : 100% Bas-fonds : - Prêt FAD N° 2100150032043 : 95% - Bénéficiaires : 5% N° d’identification Projet : P-Z1-AAZ-018 1. Le présent avis d’appel d’offres international (AAOI) suit l’avis général de passation des marchés du projet paru sur le site Développent Business et sur le portail de la Banque (www.afdb.org) le 15/10/2015, et dans l’Essor, quotidien national d’information du Mali N° 18037 du 22/10/2015. 2. Le Gouvernement de la République du Mali a reçu un financement de la Banque Africaine de Développement en divers monnaies, pour couvrir le coût du Projet 1 du Programme de Renforcement de la Résilience a l’insécurité alimentaire et nutritionnelle au Sahel (P2RS), et entend affecter une partie du produit de ce financement aux paiements relatifs aux marchés pour les Travaux de construction de Micro Barrages, de surcreusement de Mares et d’aménagement de Bas-Fonds dans les cercles de Diéma et Nioro (Région de Kayes) ; Banamba, Kolokani et Nara (Région de Koulikoro). -

Cercle De Kayes

Cercle de Kayes REPERTOIRE Des fonds clos du Cercle de Kayes (Document provisoire) 275 CARTONS- 30,25 METRES LINEAIRES Août 2010 LES ARCHIVES Les archives jouent un rôle important dans la vie administrative, économique, sociale et culturelle d’un pays. Le développement économique, social et culturel d’un pays dépend de la bonne organisation de ses archives. Les documents d’archives possèdent une valeur probatoire, sans eux, rien ne pourrait être affirmé avec certitude, car le témoignage humain est sujet à l’erreur et à l’oubli. Les documents d’archives doivent fonctionner comme le rouage essentiel de l’Administration, et fournissent des ressources indispensables à la recherche. Les archives représentent la mémoire d’un pays. La bonne organisation des archives est un des aspects de la bonne organisation administrative. Il faut que chacun ait conscience que chaque fois qu’on détruit ou laisse détruire des archives, c’est une possibilité de gouverner qui disparaît, c’est-à-dire une part du passé de notre nation. La vigilance est un devoir. 2 Série A – Actes officiels Carton A/1–A/2-A/3 : A/1 : - Projet de constitution (1958) - Loi (1959) - Loi n˚52-130 du 6 février 1952 relative à la formation des Assemblées locales - document endommagé (1952) - Loi électorale adoptée en première lecture le 24 avril 1951 par l’Assemblée nationale (1951) - Projet de loi relatif à la formation des Assemblées du Groupe et des Assemblées locales de l’AOF, l’AEF, Cameroun, Togo et Madagascar (1951) A/2 : - Ordonnance désignant un agent d’exécution. Ordonnance -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Assessment inMali Private HealthSector WORLD BANKWORKINGPAPERNO.212 THE WORLDBANK WORLD BANK WORKING PAPER NO. 212 Private Health Sector Assessment in Mali The Post-Bamako Initiative Reality Mathieu Lamiaux François Rouzaud Wendy Woods Investment Climate Advisory Services of the World Bank Group Copyright © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org 1 2 3 4 14 13 12 11 World Bank Working Papers are published to communicate the results of the Bank’s work to the devel- opment community with the least possible delay. The manuscript of this paper therefore has not been prepared in accordance with the procedures appropriate to formally-edited texts. Some sources cited in this paper may be informal documents that are not readily available. This volume is a product of the sta of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. The ndings, interpre- tations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily re ect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judg- ment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. -

IBM News - Mali

OCTOBER5 OCTOBER 2016 2016 IBM News - Mali Immigration and Border Management Technical Cooperation National Police graduates at the IOM training course on border management, Sikasso, 2016 Ucita det publica venatua vic tere consident vit vidium es contere, nicaudam oc mis cultorTibus nonsequo HIGHLIGHTSmaximolo quis vid ut poriatibea doles dusciis serecusdaes etus dolorum iuscia et pre occulles ea cus repelic Working with the Malian Building border control posts Training the Police and other Government and UN partners and installing migration IBM agencies in border on developing the National management IT systems management and travel Border Policy and IBM Strategy (MIDAS) in Gogui and Sona document examination IBM in Mali Welcome to the Newsletter of the IBM programme at the IOM Mission in Mali. IBM stands for Immigration and Border Management technical assistance that IOM has been providing globally, including to the Member States in the Sahel region. IOM works closely with the Malian Government on IBM matters. Since 2012 Mali, a conflict-affected state facing stabilization challenges, is engaged in an ongoing political and technical dialogue with the international community tackling the root causes of instability. This Newsletter provides a glimpse of recent IOM IBM activities and border management developments in Mali. CONTACTS IBM Tel: +223 20 22 76 97 [email protected] 17, Route des Morillons, IOM Mission in Mali Fax:+223 20 22 76 98 CH-1211 Geneva 19, Magnambougou https://mali.iom.int/ Switzerland Badalabogou Est +41.22.717.9111 BPE 288, Bamako, Mali © 2016 | INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION OCTOBER 2016 5 NOVEMB Borders, Security and Development In Mali, as elsewhere in the Sahel region, governance challenges and need for stronger institutional capacity to manage security threats are high on the policy agenda. -

IMRAP, Interpeace. Self-Portrait of Mali on the Obstacles to Peace. March 2015

SELF-PORTRAIT OF MALI Malian Institute of Action Research for Peace Tel : +223 20 22 18 48 [email protected] www.imrap-mali.org SELF-PORTRAIT OF MALI on the Obstacles to Peace Regional Office for West Africa Tel : +225 22 42 33 41 [email protected] www.interpeace.org on the Obstacles to Peace United Nations In partnership with United Nations Thanks to the financial support of: ISBN 978 9966 1666 7 8 March 2015 As well as the institutional support of: March 2015 9 789966 166678 Self-Portrait of Mali on the Obstacles to Peace IMRAP 2 A Self-Portrait of Mali on the Obstacles to Peace Institute of Action Research for Peace (IMRAP) Badalabougou Est Av. de l’OUA, rue 27, porte 357 Tel : +223 20 22 18 48 Email : [email protected] Website : www.imrap-mali.org The contents of this report do not reflect the official opinion of the donors. The responsibility and the respective points of view lie exclusively with the persons consulted and the authors. Cover photo : A young adult expressing his point of view during a heterogeneous focus group in Gao town in June 2014. Back cover : From top to bottom: (i) Focus group in the Ségou region, in January 2014, (ii) Focus group of women at the Mberra refugee camp in Mauritania in September 2014, (iii) Individual interview in Sikasso region in March 2014. ISBN: 9 789 9661 6667 8 Copyright: © IMRAP and Interpeace 2015. All rights reserved. Published in March 2015 This document is a translation of the report L’Autoportrait du Mali sur les obstacles à la paix, originally written in French.