How Organizational Communication Shaped the Hearst Ranch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Market Toppers Stock

• • LIVESTOCK MARKETS-COUNTRY PRICES CROP NEWS FOR FARMERS The JOURNAL gives the livestock g rower the most com prehensive a nd reliable information obtainable in the most interestmg and readable form. F r uit, grain and field crops, dairying, cattle sales, who lesale feed price•, An invaluable service to a n yone who raises livestock of any kind. vt>~etables, poultry and produce-all are covered in the J OUR N~L , together with news even ts affecting markets. You NEED the JOURNAL. VOL. 1, NO. 47 10 CENTS A COPY UNION STOCK YARDS, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 10 CENTS A COPY OCT. 25, 1923 LIVESTOCK PURCHASES HOGS ARE ACTIVE CALIFORNIA MARKET TOPPERS STOCK YAROS S[EN AT SHARP BREAK; AS GREAT FORWARD WEONESUAY TOP $8.75 STEP BY BANKER Strictly Good Idaho Bullocks Bulk Light 'Butchers This Week ! Friday Sell Readily •at $8.50 to $8.65; Stock J. Dabney Day Says Yards Will at $7.85 Pigs $6.00 to $7.00 Cause Los Angeles. to Become Live Stock Center BULK PLAIN STEERS .., FROM $6.00 TO $7.00 OVER A MILLION A MONTH FOR STOCK Cows Sharply Lower, Selling Mostly From $4.00 to $5.00; Many Huge Industries Attracted Calf Run Heavy Here by Those Behind Great Project REPRE SENTATIVE SALES BEE~· fi'l'l : rms Thurscluy, Odnhf•r 1 A .·o. ,\ ' . \\'t 1-'IH't' )fi l'tnh • • .• •••• 10 7:1 7 , 1111 I f'uhfn~nia • X7.1 7.00 17 Cuhfnruia .. 04 • 1020 7.00 5 1 l'tnh •••. •• !Jt 7 fi . :.!.t; 1 ~ l'tnh •• • . -

Sponsor 490801.Pdf

~" GUST 1949 • $8.00 a Year I Radio a udience: 1949-p. 21 RECEIVE rering farm commercial-p. 30 ~~~~ Chicago laundry story-po 24 How to sample a vacation-po 32 Even now before B. C. the G. we 're packingJ'em]in! Yes, even before Bing Crosby comes in with the spec For Fall booking with plenty of punch take note of tacular new CBS lineup in the Fall, WHAS listener the WHAS audience ratings before Bing ... add the ship figures are zooming ... outstripping all other Groaner ... then figure in the rest of the great CBS stations in the rich Kentuckiana market. Fall Lineup. It proves WHAS the gilt-edged, rock-solid buy of the '49 Kentuckiana Fall Season. 111 tlte last year WHAS was the ollly Kelltuckialla *Source: 47-48 and 48-49 Winter-Spring Reports_ station to increase its roster of top Hooperated pro grams momillg, aftemooll AND e'JIening!* ~ COFFEE CALL is an audience participation ~ show with prizes from participating sponsors. Credit this to the happy combination of CBS pro It has won 2 national awards: NRDGA National Radio gramming and WHAS shows. "Coffee Call" is a good Award ("the best woman's program") and CCNY Award example ... an aromatic blend of enthusiastic house of Merit ("most effective direct-selling program"). Talent; M,C, Jim Walton, organist Herbie Koch. Spon wives in the WHAS studio plus thousands of buy sors: Delmonico Foods, Louisville Provision Co., Van minded housewives in Kentuckiana homes. Allmen Foods. Come This fall, choice seats ( a vailabilities " to YOll) for the Creat WHAS-CBS Show will be hard to find. -

President Bush Leaves SM with Millions

FRIDAY, AUGUST 13, 2004 Volume 3, Issue 235 FREE Santa Monica Daily Press A newspaper with issues DAILY LOTTERY FANTASY 5 President Bush leaves SM with millions 2 3 4 11 16 DAILY 3 He promises to compete for California’s vote in November Daytime: 5 3 0 Evening: 2 0 0 BY JOHN WOOD medical liability, encourage new DAILY DERBY Daily Press Staff Writer 1st: 06 Whirl Win business growth and fight terrorism. 2nd: 02 Lucky Star “There’s a lot of talk in 3rd: 03 Hot Shot SM AIRPORT — More than Washington, but this administra- RACE TIME: 1:41.48 500 people gathered in a hangar tion, like Arnold Schwarzenegger here Thursday evening for a in California, is getting things NEWS OF THE WEIRD Republican Party fundraiser that done,” said Bush, who concludes BY CHUCK SHEPARD officials said netted $3 million. his 12th visit to California as pres- Guests paid up to $25,000 apiece ident this morning, flying on to ■ In Dadeville, Ala., in 1999, Mr. Gabel to nosh on roast beef filet and Taylor, 38, who had just prevailed in an Portland, Ore., Seattle, Wash., and informal Bible-quoting contest, was shot grilled asparagus, and hear from Sioux City, Idaho, before return- to death by the angry loser. And in 1998, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, first ing to the capital. the Rev. John Wayne “Punkin” Brown Jr., lady Laura Bush and President 34, died of a rattlesnake bite while minis- Bush spent the bulk of his 30- tering at the Rock House Holiness Church George W. Bush. -

Wine Coast Country Fact Sheet

WINECOASTCOUNTRY FACT SHEET Overview: WineCoastCountry, the coastal region of San Luis Obispo County located midway between Los Angeles and San Francisco, is where the best of southern and northern California meet. Spanning 101 miles of prime Pacific coastline, this spectacular region consists of 10 diverse artisan towns and seaside villages rich in character and history: Ragged Point/San Simeon, Cambria, Cayucos-by-the-Sea, unincorporated Morro Bay, Los Osos/Baywood Park, Avila Beach & Valley, Edna Valley, Arroyo Grande Valley, Oceano, and Nipomo. From lush farmland to the sparkling Pacific Ocean, the area boasts vast stretches of white sandy beaches and picturesque rugged coastline, renowned wineries, the world famous Hearst Castle, bucolic farmland, wildlife, pristine forests, beautiful state parks, fields of wild flowers, and untouched natural beauty as far as the eye can see. Website: www.WineCoastCountry.com Blog: www.WineCoastCountry.com/blog Facebook: www.facebook.com/WineCoastCountry Twitter: www.twitter.com/WineCoastCountry. Location: Easily accessible from both the San Francisco Bay Area and Los Angeles, the northern most tip of WineCoastCountry begins in San Simeon at Ragged Point, 191 miles south of San Francisco, and the southern most tip is located in Nipomo, 165 miles northwest of Los Angeles. It is approximately a 3.5-4 hour drive south from San Francisco and north from Los Angeles. Getting There: WineCoastCountry is easily accessible from San Luis Obispo Regional Airport (8.57mi/13.8km). Direct flights are offered from San Francisco, Los Angeles and Phoenix. For more information, contact (805) 781-5205. WineCoastCountry can also be reached by ground or rail transportation from both San Francisco Airport (231.59mi/372.7); Santa Barbara Airport (86.19mi/138.7km); Los Angeles International Airport (177.39mi/138.7km), Burbank-Glendale-Pasadena Airport (170.36mi/274.17km); rail service is provided by Amtrak with numerous stations located throughout the region. -

Carmel Pine Cone, March 13, 2009 (Main News)

How fast could Student’s letter to They went all out you move without Obama stands out for new restaurant hip bones? from the crowd — INSIDE THIS WEEK BULK RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID CARMEL, CA Permit No. 149 Volume 95 No. 11 On the Internet: www.carmelpinecone.com March 13-19, 2009 Y OUR S OURCE F OR L OCAL N EWS, ARTS AND O PINION S INCE 1915 State parks policy: VIPs lobbied to Dogs allowed only where it’s paved help replace ■ Canines banned dog in the canyon, which was formerly designated as the Pfeiffer bridge in Hatton Canyon route for a highway. “They should have just put up a sign By KELLY NIX By CHRIS COUNTS that said that dogs have to be on leashes.” TIRED OF waiting around for the state to free up money A NEW ban on dogs in He called the posting of the so a vital bridge at Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park can be Hatton Canyon has upset sev- signs “a rotten thing to do” and installed, nearby resident Jack Ellwanger is petitioning local eral residents who have long suggested that he would now be politicians for help. walked their pets in the area. forced to walk his dog along In December, financing was frozen for about 5,600 infra- Meanwhile, a state park offi- Highway 1, which he considers structure projects around the state, including plans to install cial said the ban is only tempo- “dangerous when you’re walk- a new bridge at the entrance to the Big Sur park. -

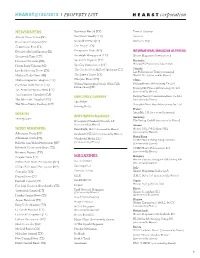

Hearst@125/2012 Property List

HEARST@125/2012 x PROPERTY LIST NEWSPAPERS Northeast Herald (TX) Town & Country Albany Times Union (NY) Northwest Weekly (TX) Veranda Beaumont Enterprise (TX) Norwalk Citizen (CT) Woman’s Day Connecticut Post (CT) Our People (TX) Edwardsville Intelligencer (IL) Pennysaver News (NY) INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE ACTIVITIES Greenwich Time (CT) Randolph Wingspread (TX) Hearst Magazines International Houston Chronicle (TX) Southside Reporter (TX) Australia Hearst/ACP (50% owned by Hearst) Huron Daily Tribune (MI) Spa City Moneysaver (NY) The Greater New Milford Spectrum (CT) Canada Laredo Morning Times (TX) Les Publications Transcontinental Midland Daily News (MI) The Zapata Times (TX) Hearst Inc. (49% owned by Hearst) Midland Reporter-Telegram (TX) Westport News (CT) China Beijing Hearst Advertising Co. Ltd. Plainview Daily Herald (TX) Wilton/Gansevoort/South Glens Falls Moneysaver (NY) Beijing MC Hearst Advertising Co. Ltd. San Antonio Express-News (TX) (49% owned by Hearst) San Francisco Chronicle (CA) DIRECTORIES COMPANY Beijing Trends Communications Co. Ltd. The Advocate, Stamford (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) LocalEdge The News-Times, Danbury (CT) Shanghai Next Idea Advertising Co., Ltd. Metrix4Media France WEBSITES Inter-Edi, S.A. (50% owned by Hearst) INVESTMENTS/ALLIANCES Seattlepi.com Germany Newspaper National Network, LP Elle Verlag GmbH (50% owned by Hearst) (5.75% owned by Hearst) Greece WEEKLY NEWSPAPERS NewsRight, LLC (7.2% owned by Hearst) Hearst DOL Publishing S.R.L. (50% owned by Hearst) Advertiser North (NY) quadrantONE, LLC (25% owned by Hearst) Advertiser South (NY) Hong Kong Wanderful Media, LLC SCMP Hearst Hong Kong Limited (12.5% owned by Hearst) Ballston Spa/Malta Pennysaver (NY) (30% owned by Hearst) Bulverde Community News (TX) SCMP Hearst Publications Ltd. -

Guide to the Julia Morgan Papers, 1835 – 1958

Guide to the Julia Morgan Papers, 1835 – 1958 http://www.lib.calpoly.edu/specialcollections/findingaids/ms010/ Julia Morgan Papers, 1835–1958 (bulk 1896–1945) Processed by Nancy Loe and Denise Fourie, 2006, revised October 2008; encoded by Byte Managers, 2007 Special Collections Robert E. Kennedy Library 1 Grand Avenue California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 Phone: 805/756-2305 Fax: 805/756-5770 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.calpoly.edu/specialcollections/ © 1985, 2007 Trustees of the California State University. All rights reserved. Table of Contents DESCRIPTIVE SUMMARY 5 TITLE: 5 COLLECTION NUMBER: 5 CREATOR: 5 ABSTRACT: 5 EXTENT: 5 LANGUAGES: 5 REPOSITORY: 5 ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION 6 PROVENANCE: 6 ACCESS: 6 RESTRICTIONS ON USE AND REPRODUCTION: 6 PREFERRED CITATION: 6 ABBREVIATIONS USED: 6 FUNDING: 6 INDEXING TERMS 7 SUBJECTS: 7 GENRES AND FORMS OF MATERIAL: 7 RELATED MATERIALS 8 MATERIALS CATALOGED SEPARATELY: 8 RELATED COLLECTIONS: 8 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE 10 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE 12 SERIES DESCRIPTIONS/CONTAINER LIST 14 SERIES 1. PERSONAL PAPERS, 1835–1958 14 A. BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION 14 B. FAMILY CORRESPONDENCE AND RECORDS 14 C. PERSONAL CORRESPONDENCE 15 D. DIARIES 16 E. EDUCATION/STUDENT WORK 16 F. FINANCIAL RECORDS AND INVESTMENTS 17 G. TRAVEL 18 H. PHOTOGRAPHS 18 - 2 - SERIES 2. PROFESSIONAL PAPERS, 1904–1957 21 A. AWARDS 21 B. ASSOCIATIONS AND COMMITTEES 21 C. CERTIFICATIONS 21 D. PROFESSIONAL CORRESPONDENCE 22 E. RESEARCH NOTES AND PHOTOGRAPHS 22 F. REFERENCE FILES AND PHOTOGRAPHS 23 SERIES 3. OFFICE RECORDS, 1904–1945 26 A. CARD FILES AND LISTS 26 B. CORRESPONDENCE–CLIENTS, COLLEAGUES AND STAFF 27 C. -

Corporate Registry Registrar's Periodical Template

Service Alberta ____________________ Corporate Registry ____________________ Registrar’s Periodical REGISTRAR’S PERIODICAL, APRIL 15, 2016 SERVICE ALBERTA Corporate Registrations, Incorporations, and Continuations (Business Corporations Act, Cemetery Companies Act, Companies Act, Cooperatives Act, Credit Union Act, Loan and Trust Corporations Act, Religious Societies’ Land Act, Rural Utilities Act, Societies Act, Partnership Act) 01 CONTRACTING INC. Named Alberta Corporation 1948252 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Incorporated 2016 MAR 11 Registered Address: 225 - Corporation Incorporated 2016 MAR 05 Registered 10TH AVENUE SW, HIGH RIVER ALBERTA, T1V Address: 4 AUBURN GLEN COMMON SE, 1A7. No: 2019564794. CALGARY ALBERTA, T3M 0N2. No: 2019482526. 0180 MIRROR AND SHINE CORP. Named Alberta 1948685 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Corporation Incorporated 2016 MAR 14 Registered Corporation Incorporated 2016 MAR 01 Registered Address: 7503 73 AVE, EDMONTON ALBERTA, T6C Address: UNIT F, 55 - 2 STREET, STRATHMORE 0B8. No: 2019567581. ALBERTA, T1P 1V6. No: 2019486857. 101115405 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other 1948831 ALBERTA INC. Numbered Alberta Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2016 MAR 07 Corporation Incorporated 2016 MAR 07 Registered Registered Address: RR4 SITE 3 COMP 54, STONY Address: 650 ARBOUR LAKE DRIVE NW, PLAIN ALBERTA, T7Z1X4. No: 2119551907. CALGARY ALBERTA, T3G 4T6. No: 2019488317. 101274708 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other 1949387 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2016 MAR 09 Corporation Incorporated 2016 MAR 11 Registered Registered Address: 3000, 700 - 9TH AVENUE SW, Address: 53 BEAVER STREET, WHITECOURT CALGARY ALBERTA, T2P3V4. No: 2119556732. ALBERTA, T7S 1G5. No: 2019493879. 101296182 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other 1949899 ALBERTA LTD. Numbered Alberta Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2016 MAR 07 Corporation Incorporated 2016 MAR 13 Registered Registered Address: 310, 1212 - 31 AVENUE NE, Address: 297 CHAPARRAL DRIVE SE, CALGARY CALGARY ALBERTA, T2E7S8. -

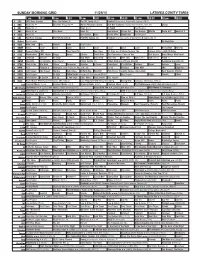

Sunday Morning Grid 11/29/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/29/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Jacksonville Jaguars. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å World/Adventure Sports Red Bull Signature Series From Pomona, Calif. (N) Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife World of X World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Washington Redskins. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program 12 Dog Days 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Deepak Chopra MD Easy Yoga Pain Fear Cure 21 Days to a Slimmer Younger You Jacques Pepin’s 80th Birthday 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids The Carpenters: Close to You Rick Steves Brain Maker With David 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bob Show Bob Show Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Psych Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio de Abu Dabi. -

William Randolph Hearst Papers, 1874-1951 (Bulk 1927-1947)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6n39q43j Online items available Finding Aid to the William Randolph Hearst Papers, 1874-1951 (bulk 1927-1947) Processed by Elizabeth Stephens, Rebecca Kim, and Eric Crawley. The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the William BANC MSS 77/121 c 1 Randolph Hearst Papers, 1874-1951 (bulk 1927-1947) Finding Aid to the William Randolph Hearst Papers, 1874-1951 (bulk 1927-1947) Collection number: BANC MSS 77/121 c The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Finding Aid Author(s): Processed by Elizabeth Stephens, Rebecca Kim, and Eric Crawley. Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: William Randolph Hearst papers Date (inclusive): 1874-1951 Date (bulk): 1927-1947 Collection Number: BANC MSS 77/121 c Creator: Hearst, William Randolph, 1908-1993 Extent: Number of containers: 14 boxes, 46 cartons, 8 oversize folders, 9 oversize boxes Linear feet: 6621 digital objects (24 images) Repository: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: Consists of a portion of William Randolph Hearst's business and personal office files primarily for the years 1927-1929, 1937-1938, and 1944-1947. -

The California Morgans Of

u HISTORY LESSON u WILLIAMThe CaliforniaRANDOLPH Morgans HEARST of Did you know that the eccentric American publisher, art-collector and builder of the famous San Simeon castle, also bred Morgan horses for ranch work? By Brenda L. Tippin he story of the Hearst Morgans is one intertwined with some local lead mines in Missouri. His father had died when he the building of California, steeped in the history of the was about 22, leaving some $10,000 in debt, a huge amount for ancient vaqueros, yet overshadowed by a magnificent those times. George worked hard to care for his mother, sister, castle and a giant family corporation still in existence and a crippled brother who later died, and succeeded in paying off Ttoday. Although the short-lived program was not begun until these debts. With news of the California Gold Rush he made his William Randolph Hearst was in his late 60s, like everything else way to San Francisco after a difficult journey across country, and Hearst, the Morgan breeding was conducted on a grand scale. from there, began to try his fortunes in various mining camps, and Shaped by the fascinating story of the Hearst family and the early also buying and selling mining shares. Vaquero traditions, the Hearst Morgan has left a lasting influence His first real success came with the Ophir Mine of the on the Morgans of today, especially those of performance and Comstock Lode, the famous silver mines of Nevada. In 1853, Western working lines. George Hearst formed a partnership with James Ben Ali Haggin and Lloyd Tevis. -

John Francis Neylan Papers, Circa 1911-1960

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf0q2n97zs No online items Finding Aid to the John Francis Neylan Papers, circa 1911-1960 Finding Aid written by Bancroft Library staff; revised by Alison E. Bridger in 2006. The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2006 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the John Francis BANC MSS C-B 881 1 Neylan Papers, circa 1911-1960 Finding Aid to the John Francis Neylan Papers, circa 1911-1960 Collection Number: BANC MSS C-B 881 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Bancroft Library staff; revised by Alison E. Bridger in 2006. Date Completed: June 2006 © 2006 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: John Francis Neylan papers Date (inclusive): circa 1911-1960 Collection Number: BANC MSS C-B 881 Creators : Neylan, John Francis, 1885-1960 Extent: Number of containers: 202 boxes, 2 volumes, 12 cartons and 4 oversize foldersLinear feet: 96.4 Repository: The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Abstract: Contains correspondence, memoranda, reports, speeches, articles, clippings, scrapbooks and printed material relating to: his work as chairman of the California State Board of Control during Hiram Johnson's administration; as publisher of the San Francisco Call; Neylan's work on the Board of Regents for the University of California, including the Loyalty Oath Controversy, the Committee on Atomic Energy Commission Projects, and the Committee on Finance; his association and handling of the business affairs of William Randolph Hearst; his involvement in the Charlotte Anita Whitney case; his involvement in the Baugh and Abbott vs.