PKCS #11: Cryptographic Token Interface Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public-Key Cryptography

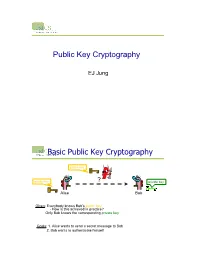

Public Key Cryptography EJ Jung Basic Public Key Cryptography public key public key ? private key Alice Bob Given: Everybody knows Bob’s public key - How is this achieved in practice? Only Bob knows the corresponding private key Goals: 1. Alice wants to send a secret message to Bob 2. Bob wants to authenticate himself Requirements for Public-Key Crypto ! Key generation: computationally easy to generate a pair (public key PK, private key SK) • Computationally infeasible to determine private key PK given only public key PK ! Encryption: given plaintext M and public key PK, easy to compute ciphertext C=EPK(M) ! Decryption: given ciphertext C=EPK(M) and private key SK, easy to compute plaintext M • Infeasible to compute M from C without SK • Decrypt(SK,Encrypt(PK,M))=M Requirements for Public-Key Cryptography 1. Computationally easy for a party B to generate a pair (public key KUb, private key KRb) 2. Easy for sender to generate ciphertext: C = EKUb (M ) 3. Easy for the receiver to decrypt ciphertect using private key: M = DKRb (C) = DKRb[EKUb (M )] Henric Johnson 4 Requirements for Public-Key Cryptography 4. Computationally infeasible to determine private key (KRb) knowing public key (KUb) 5. Computationally infeasible to recover message M, knowing KUb and ciphertext C 6. Either of the two keys can be used for encryption, with the other used for decryption: M = DKRb[EKUb (M )] = DKUb[EKRb (M )] Henric Johnson 5 Public-Key Cryptographic Algorithms ! RSA and Diffie-Hellman ! RSA - Ron Rives, Adi Shamir and Len Adleman at MIT, in 1977. • RSA -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

A Password-Based Key Derivation Algorithm Using the KBRP Method

American Journal of Applied Sciences 5 (7): 777-782, 2008 ISSN 1546-9239 © 2008 Science Publications A Password-Based Key Derivation Algorithm Using the KBRP Method 1Shakir M. Hussain and 2Hussein Al-Bahadili 1Faculty of CSIT, Applied Science University, P.O. Box 22, Amman 11931, Jordan 2Faculty of Information Systems and Technology, Arab Academy for Banking and Financial Sciences, P.O. Box 13190, Amman 11942, Jordan Abstract: This study presents a new efficient password-based strong key derivation algorithm using the key based random permutation the KBRP method. The algorithm consists of five steps, the first three steps are similar to those formed the KBRP method. The last two steps are added to derive a key and to ensure that the derived key has all the characteristics of a strong key. In order to demonstrate the efficiency of the algorithm, a number of keys are derived using various passwords of different content and length. The features of the derived keys show a good agreement with all characteristics of strong keys. In addition, they are compared with features of keys generated using the WLAN strong key generator v2.2 by Warewolf Labs. Key words: Key derivation, key generation, strong key, random permutation, Key Based Random Permutation (KBRP), key authentication, password authentication, key exchange INTRODUCTION • The key size must be long enough so that it can not Key derivation is the process of generating one or be easily broken more keys for cryptography and authentication, where a • The key should have the highest possible entropy key is a sequence of characters that controls the process (close to unity) [1,2] of a cryptographic or authentication algorithm . -

Key Derivation Functions and Their GPU Implementation

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY}w¡¢£¤¥¦§¨ OF I !"#$%&'()+,-./012345<yA|NFORMATICS Key derivation functions and their GPU implementation BACHELOR’S THESIS Ondrej Mosnáˇcek Brno, Spring 2015 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ cbna ii Declaration Hereby I declare, that this paper is my original authorial work, which I have worked out by my own. All sources, references and literature used or excerpted during elaboration of this work are properly cited and listed in complete reference to the due source. Ondrej Mosnáˇcek Advisor: Ing. Milan Brož iii Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor for his guidance and support, and also for his extensive contributions to the Cryptsetup open- source project. Next, I would like to thank my family for their support and pa- tience and also to my friends who were falling behind schedule just like me and thus helped me not to panic. Last but not least, access to computing and storage facilities owned by parties and projects contributing to the National Grid In- frastructure MetaCentrum, provided under the programme “Projects of Large Infrastructure for Research, Development, and Innovations” (LM2010005), is also greatly appreciated. v Abstract Key derivation functions are a key element of many cryptographic applications. Password-based key derivation functions are designed specifically to derive cryptographic keys from low-entropy sources (such as passwords or passphrases) and to counter brute-force and dictionary attacks. However, the most widely adopted standard for password-based key derivation, PBKDF2, as implemented in most applications, is highly susceptible to attacks using Graphics Process- ing Units (GPUs). -

Authentication and Key Distribution in Computer Networks and Distributed Systems

13 Authentication and key distribution in computer networks and distributed systems Rolf Oppliger University of Berne Institute for Computer Science and Applied Mathematics {JAM) Neubruckstrasse 10, CH-3012 Bern Phone +41 31 631 89 51, Fax +41 31 631 39 65, [email protected] Abstract Authentication and key distribution systems are used in computer networks and dis tributed systems to provide security services at the application layer. There are several authentication and key distribution systems currently available, and this paper focuses on Kerberos (OSF DCE), NetSP, SPX, TESS and SESAME. The systems are outlined and reviewed with special regard to the security services they offer, the cryptographic techniques they use, their conformance to international standards, and their availability and exportability. Keywords Authentication, key distribution, Kerberos, NetSP, SPX, TESS, SESAME 1 INTRODUCTION Authentication and key distribution systems are used in computer networks and dis tributed systems to provide security services at the application layer. There are several authentication and key distribution systems currently available, and this paper focuses on Kerberos (OSF DCE), NetSP, SPX, TESS and SESAME. The systems are outlined and reviewed with special regard to the security services they offer, the cryptographic techniques they use, their conformance to international standards, and their availability and exportability. It is assumed that the reader of this paper is familiar with the funda mentals of cryptography, and the use of cryptographic techniques in computer networks and distributed systems (Oppliger, 1992 and Schneier, 1994). The following notation is used in this paper: • Capital letters are used to refer to principals (users, clients and servers). -

Harris Sierra II, Programmable Cryptographic

TYPE 1 PROGRAMMABLE ENCRYPTION Harris Sierra™ II Programmable Cryptographic ASIC KEY BENEFITS When embedded in radios and other voice and data communications equipment, > Legacy algorithm support the Harris Sierra II Programmable Cryptographic ASIC encrypts classified > Low power consumption information prior to transmission and storage. NSA-certified, it is the foundation > JTRS compliant for the Harris Sierra II family of products—which includes two package options for the ASIC and supporting software. > Compliant with NSA’s Crypto Modernization Program The Sierra II ASIC offers a broad range of functionality, with data rates greater than 300 Mbps, > Compact form factor legacy algorithm support, advanced programmability and low power consumption. Its software programmability provides a low-cost migration path for future upgrades to embedded communications equipment—without the logistics and cost burden normally associated with upgrading hardware. Plus, it’s totally compliant with all Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS) and Crypto Modernization Program requirements. The Sierra II ASIC’s small size, low power requirements, and high data rates make it an ideal choice for battery-powered applications, including military radios, wireless LANs, remote sensors, guided munitions, UAVs and any other devices that require a low-power, programmable solution for encryption. Specifications for: Harris SIERRA II™ Programmable Cryptographic ASIC GENERAL BATON/MEDLEY SAVILLE/PADSTONE KEESEE/CRAYON/WALBURN Type 1 – Cryptographic GOODSPEED Algorithms* ACCORDION FIREFLY/Enhanced FIREFLY JOSEKI Decrypt High Assurance AES DES, Triple DES Type 3 – Cryptographic AES Algorithms* Digital Signature Standard (DSS) Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA) Type 4 – Cryptographic CITADEL® Algorithms* SARK/PARK (KY-57, KYV-5 and KG-84A/C OTAR) DS-101 and DS-102 Key Fill Key Management SINCGARS Mode 2/3 Fill Benign Key/Benign Fill *Other algorithms can be added later. -

Public Key Cryptography Public Key Cryptography

Public Key Cryptography Public Key Cryptography • Symmetric Key: – Same key used for encryption and decrypiton – Same key used for message integrity and validation • Public-Key Cryptography – Use one key to encrypt or sign messages – Use another key to decrypt or validate messages • Keys – Public key known to the world and used to send you a message – Only your private key can decrypt the message Public Key Private Key Plaintext Ciphertext Plaintext Encryption Decryption ENTS 689i | Network Immunity | Fall 2008 Lecture 2 Public Key Cryptography • Motivations – In symmetric key cryptography, a key was needed between every pair of users wishing to securely communicate • O(n2) keys – Problem of establishing a key with remote person with whom you wish to communicate • Advantages to Public Key Cryptography – Key distribution much easier: everyone can known your public key as long as your private key remains secret – Fewer keys needed • O(n) keys • Disadvantages – Slow, often up to 1000x slower than symmetric-key cryptography ENTS 689i | Network Immunity | Fall 2008 Lecture 2 Cryptography and Complexity • Three classes of complexity: – P: solvable in polynomial time, O(nc) – NP: nondeterministic solutions in polynomial time, deterministic solutions in exponential time – EXP: exponential solutions, O(cn) • Cryptographic problems should be: increasing P – Encryption should be P difficult – Decryption should be P with key NP – Decryption should be NP for attacker EXP • Need problems where complexity of solution depends on knowledge of a key ENTS -

An Archeology of Cryptography: Rewriting Plaintext, Encryption, and Ciphertext

An Archeology of Cryptography: Rewriting Plaintext, Encryption, and Ciphertext By Isaac Quinn DuPont A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto © Copyright by Isaac Quinn DuPont 2017 ii An Archeology of Cryptography: Rewriting Plaintext, Encryption, and Ciphertext Isaac Quinn DuPont Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto 2017 Abstract Tis dissertation is an archeological study of cryptography. It questions the validity of thinking about cryptography in familiar, instrumentalist terms, and instead reveals the ways that cryptography can been understood as writing, media, and computation. In this dissertation, I ofer a critique of the prevailing views of cryptography by tracing a number of long overlooked themes in its history, including the development of artifcial languages, machine translation, media, code, notation, silence, and order. Using an archeological method, I detail historical conditions of possibility and the technical a priori of cryptography. Te conditions of possibility are explored in three parts, where I rhetorically rewrite the conventional terms of art, namely, plaintext, encryption, and ciphertext. I argue that plaintext has historically been understood as kind of inscription or form of writing, and has been associated with the development of artifcial languages, and used to analyze and investigate the natural world. I argue that the technical a priori of plaintext, encryption, and ciphertext is constitutive of the syntactic iii and semantic properties detailed in Nelson Goodman’s theory of notation, as described in his Languages of Art. I argue that encryption (and its reverse, decryption) are deterministic modes of transcription, which have historically been thought of as the medium between plaintext and ciphertext. -

Cryptool 2 in Teaching Cryptography

Journal of Computations & Modelling, vol.4, no.1, 2014, 349-358 ISSN: 1792-7625 (print), 1792-8850 (online) Scienpress Ltd, 2014 Cryptool 2 in Teaching Cryptography Major Konstantinos Loussios1 Abstract. Considering the value it had in the past, has continued to the present and will continue to have, perhaps to an even greater extent in the future concealing information during transmission or transport, leads automatically to attempt to discover the importance and the value of the means, methods and techniques used to implement the concealment. Cryptography is a branch of computer science attracts the attention with its great utility that has nowadays. Given therefore deemed necessary to standardize, analyze and present the encryption algorithms to learning and training on the operation with as efficiently and easily as possible. Having in mind that the theory must be accompanied by practice and examples that help to consolidate the syllabi material, we felt that the analytical presentation of an educational tool on learning algorithms of cryptography is a way of learning while embedding. The learning tool cryptool 2 is an implementation of all the above, and through this we will try to show, those essential functions, which help the user with visual and practical way, to see in detail all the properties and functional details of the algorithms contained, will present representative examples of functioning algorithms, we proceed to create digital signatures and will implement the cryptanalysis algorithms. The above is an object of study and teaching in the professional area of land, in the field of communications and transmissions-service systems. Knowing, however, that historically since the antiquity, first we Greeks, we use encryption in a simple form, for military purposes, but later down through the years and fighting wars around the world, the art encryption and decryption evolved and became object of all armies and weapons. -

The Double Ratchet Algorithm

The Double Ratchet Algorithm Trevor Perrin (editor) Moxie Marlinspike Revision 1, 2016-11-20 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Overview 3 2.1. KDF chains . 3 2.2. Symmetric-key ratchet . 5 2.3. Diffie-Hellman ratchet . 6 2.4. Double Ratchet . 13 2.6. Out-of-order messages . 17 3. Double Ratchet 18 3.1. External functions . 18 3.2. State variables . 19 3.3. Initialization . 19 3.4. Encrypting messages . 20 3.5. Decrypting messages . 20 4. Double Ratchet with header encryption 22 4.1. Overview . 22 4.2. External functions . 26 4.3. State variables . 26 4.4. Initialization . 26 4.5. Encrypting messages . 27 4.6. Decrypting messages . 28 5. Implementation considerations 29 5.1. Integration with X3DH . 29 5.2. Recommended cryptographic algorithms . 30 6. Security considerations 31 6.1. Secure deletion . 31 6.2. Recovery from compromise . 31 6.3. Cryptanalysis and ratchet public keys . 31 1 6.4. Deletion of skipped message keys . 32 6.5. Deferring new ratchet key generation . 32 6.6. Truncating authentication tags . 32 6.7. Implementation fingerprinting . 32 7. IPR 33 8. Acknowledgements 33 9. References 33 2 1. Introduction The Double Ratchet algorithm is used by two parties to exchange encrypted messages based on a shared secret key. Typically the parties will use some key agreement protocol (such as X3DH [1]) to agree on the shared secret key. Following this, the parties will use the Double Ratchet to send and receive encrypted messages. The parties derive new keys for every Double Ratchet message so that earlier keys cannot be calculated from later ones. -

On the Security of the PKCS#1 V1.5 Signature Scheme

On the Security of the PKCS#1 v1.5 Signature Scheme Tibor Jager1 Saqib A. Kakvi1 Alexander May2 September 10, 2018 1Department of Computer Science, Universitat¨ Paderborn ftibor.jager,[email protected] 2Hortz Gortz¨ Institute, Ruhr Universitat¨ Bochum [email protected] Abstract The RSA PKCS#1 v1.5 signature algorithm is the most widely used digital signature scheme in practice. Its two main strengths are its extreme simplicity, which makes it very easy to implement, and that verification of signatures is significantly faster than for DSA or ECDSA. Despite the huge practical importance of RSA PKCS#1 v1.5 signatures, providing formal evidence for their security based on plausible cryptographic hardness assumptions has turned out to be very difficult. Therefore the most recent version of PKCS#1 (RFC 8017) even recommends a replacement the more complex and less efficient scheme RSA-PSS, as it is provably secure and therefore considered more robust. The main obstacle is that RSA PKCS#1 v1.5 signatures use a deterministic padding scheme, which makes standard proof techniques not applicable. We introduce a new technique that enables the first security proof for RSA-PKCS#1 v1.5 signatures. We prove full existential unforgeability against adaptive chosen-message attacks (EUF-CMA) under the standard RSA assumption. Furthermore, we give a tight proof under the Phi-Hiding assumption. These proofs are in the random oracle model and the parameters deviate slightly from the standard use, because we require a larger output length of the hash function. However, we also show how RSA-PKCS#1 v1.5 signatures can be instantiated in practice such that our security proofs apply. -

TRANSPORT LAYER SECURITY (TLS) Lokesh Phani Bodavula

TRANSPORT LAYER SECURITY (TLS) Lokesh Phani Bodavula October 2015 Abstract 1 Introduction The security of Electronic commerce is completely in the hands of Cryptogra- phy. Most of the transactions through e-commerce sites, auction sites, on-line banking, stock trading and many more are exchanged over the network. SSL or TLS are the additional layers that are required in order to obtain authen- tication, privacy and integrity for all kinds of communication going through network. This paper focuses on the additional layer (TLS) which is responsi- ble for the whole communication. Transport Layer Security is a protocol that is responsible for offering privacy between the communicating applications and their users on Internet. TLS is inserted between the application layer and the network layer-where the session layer is in the OSI model TLS, however, requires a reliable transport channel-typically TCP. 2 History Instead of the end-to-end argument and the S-HTTP proposal the developers at Netscape Communications introduced an interesting secured connection concept of low-layer and high-layer security. For achieving this type of security there em- ployed a new intermediate layer between the transport layer and the application layer which is called as Secure Sockets Layer (SSL). SSL is the starting stage for the evolution of different transport layer security protocols. Technically SSL protocol is assigned to the transport layer because of its functionality is deeply inter-winded with the one of a transport layer protocol like TCP. Coming to history of Transport layer protocols as soon as the National Center for Super- computing Application (NCSA) released the first popular Web browser called Mosaic 1.0 in 1993, Netscape Communications started working on SSL protocol.