Gas Phase Detection and Rotational Spectroscopy of Ethynethiol, HCCSH Arxiv:1811.12798V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 30 Nov 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Patent Office Patented Jan

3,071,593 United States Patent Office Patented Jan. 1, 1963 2 3,071,593 O PREPARATION OF AELKENE SULFES Paul F. Warner, Philips, Tex., assignor to Philips Petroleum Company, a corporation of Delaware wherein each R is selected from the group consisting of No Drawing. Filed July 27, 1959, Ser. No. 829,518 5 hydrogen, alkyl, aryl, alkaryl, aralkyl and cycloalkyl 8 Claims. (C. 260-327) groups having 1 to 8 carbon atoms, the combined R groups having up to 12 carbon atoms. Examples of Suit This invention relates to a method of preparing alkene able compounds are ethylene oxide, propylene oxide, iso sulfides. Another aspect relates to a method of convert butylene oxide, a-amylene oxide, styrene oxide, isopropyl ing an alkene oxide to the corresponding sulfide at rela O ethylene oxide, methylethylethylene oxide, 3-phenyl-1, tively high yields without refrigeration. 2-propylene oxide, (3-methylphenyl) ethylene oxide, By the term "alkene sulfide' as used in this specifica cyclohexylethylene oxide, 1-phenyl-3,4-epoxyhexane, and tion and in the claims, I mean to include not only un the like. substituted alkene sulfides such as ethylene sulfide, propyl The salts of thiocyanic acid which I prefer to use are ene sulfide, isobutylene sulfide, and the like, but also 5 the salts of the alkali metals or ammonium. I especially hydrocarbon-substituted alkene sulfides such as styrene prefer ammonium thiocyanate, sodium thiocyanate, and oxide, and in general all compounds conforming to the potassium thiocyanate. These compounds can be reacted formula with ethylene oxide in a cycloparaffin diluent to produce 20 substantial yields of ethylene sulfide and with little or S no polymer formation. -

House Fly Attractants and Arrestante: Screening of Chemicals Possessing Cyanide, Thiocyanate, Or Isothiocyanate Radicals

House Fly Attractants and Arrestante: Screening of Chemicals Possessing Cyanide, Thiocyanate, or Isothiocyanate Radicals Agriculture Handbook No. 403 Agricultural Research Service UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Contents Page Methods 1 Results and discussion 3 Thiocyanic acid esters 8 Straight-chain nitriles 10 Propionitrile derivatives 10 Conclusions 24 Summary 25 Literature cited 26 This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife—if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides and pesticide containers. ¿/áepé4áaUÁí^a¡eé —' ■ -"" TMK LABIL Mention of a proprietary product in this publication does not constitute a guarantee or warranty by the U.S. Department of Agriculture over other products not mentioned. Washington, D.C. Issued July 1971 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 25 cents House Fly Attractants and Arrestants: Screening of Chemicals Possessing Cyanide, Thiocyanate, or Isothiocyanate Radicals BY M. S. MAYER, Entomology Research Division, Agricultural Research Service ^ Few chemicals possessing cyanide (-CN), thio- cyanate was slightly attractive to Musca domes- eyanate (-SCN), or isothiocyanate (~NCS) radi- tica, but it was considered to be one of the better cals have been tested as attractants for the house repellents for Phormia regina (Meigen). -

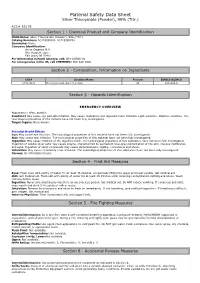

Material Safety Data Sheet

Material Safety Data Sheet Silver Thiocyanate (Powder), 99% (Titr.) ACC# 55179 Section 1 - Chemical Product and Company Identification MSDS Name: Silver Thiocyanate (Powder), 99% (Titr.) Catalog Numbers: AC419390000, AC419390250 Synonyms: None. Company Identification: Acros Organics N.V. One Reagent Lane Fair Lawn, NJ 07410 For information in North America, call: 800-ACROS-01 For emergencies in the US, call CHEMTREC: 800-424-9300 Section 2 - Composition, Information on Ingredients CAS# Chemical Name Percent EINECS/ELINCS 1701-93-5 Thiocyanic Acid, Silver(1+) Salt 99 216-934-9 Section 3 - Hazards Identification EMERGENCY OVERVIEW Appearance: white powder. Caution! May cause eye and skin irritation. May cause respiratory and digestive tract irritation. Light sensitive. Moisture sensitive. The toxicological properties of this material have not been fully investigated. Target Organs: None known. Potential Health Effects Eye: May cause eye irritation. The toxicological properties of this material have not been fully investigated. Skin: May cause skin irritation. The toxicological properties of this material have not been fully investigated. Ingestion: May cause irritation of the digestive tract. The toxicological properties of this substance have not been fully investigated. Ingestion of soluble silver salts may cause argyria, characterized by permanent blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, mucous membranes, and eyes. Ingestion of silver compounds may cause abdominal pain, rigidity, convulsions and shock. Inhalation: May cause respiratory tract irritation. The toxicological properties of this substance have not been fully investigated. Chronic: No information found. Section 4 - First Aid Measures Eyes: Flush eyes with plenty of water for at least 15 minutes, occasionally lifting the upper and lower eyelids. -

Thiocyanate Reagent Product Code R-1305K Recommended Use Use As Directed by Manufacturer for Purposes Directly Related to Water Testing

SAFETY DATA SHEET 1. Identification Product identifier Thiocyanate Reagent Product code R-1305K Recommended use Use as directed by manufacturer for purposes directly related to water testing. Recommended restrictions None known Manufacturer/Importer/Supplier/Distributor information Manufacturer Company name Anderson Chemical Company Address 325 South Davis Avenue Litchfield, MN 55355 United States Telephone (320) 693-2477 Monday─Friday, 8:00 a.m.–4:30 p.m. Website www.accomn.com E-mail [email protected] Emergency phone number (800) 424-9300 2. Hazard(s) identification Physical hazards This mixture does not meet the classification criteria according to OSHA HazCom 2012. Health hazards This mixture does not meet the classification criteria according to OSHA HazCom 2012. Environmental hazards Not currently regulated by OSHA. For additional information, refer to section 12 of the SDS. Label elements None required Signal word None required Hazard statement None required Precautionary statement Prevention None required Response None required Storage None required Disposal None required Hazard(s) not otherwise classified None Supplemental information None 3. Composition/information on ingredients Mixtures Chemical name Common name and synonyms CAS number % Deionized water Dihydrogen oxide 7732-18-5 95–99 Potassium thiocyanate Thiocyanic acid, potassium salt 333-20-0 0.1–5 4. First-aid measures Inhalation Move to fresh air. Give oxygen or artificial respiration if needed. Get medical attention immediately. Skin contact Immediately wash skin with soap and water. If symptoms persist or in all cases of concern, seek medical advice. Material name: Thiocyanate Reagent; R-1305K SDS U.S. Page 1 of 8 Eye contact Immediately flush eyes with plenty of water for at least 20 minutes. -

Ammonium Thiocyanate

AMMONIUM THIOCYANATE PRODUCT IDENTIFICATION CAS NO. 1762-95-4 EINECS NO. 217-175-6 FORMULA NH 4SCN MOL WT. 76.12 H.S. CODE 2838.00 TOXICITY Oral Rat LD50: 750 mg/kg SYNONYMS Thiocyanic acid, ammonium salt; Amthio; ammonium sulfocanide; ammonium sulphocyanide; ammonium rhodanide; ammonium sulphocyanate; Ammonium Rhodonide; Amthio; Ammonium sulfocyanate; DERIVATION CLASSIFICATION PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL PROPERTIES PHYSICAL STATE Colorless, deliquescent crystals MELTING POINT 150 C BOILING POINT SPECIFIC GRAVITY 1.31 SOLUBILITY IN WATER Soluble SOLVENT SOLUBILITY Soluble : acetone, alcohol, and ammonia pH 4.5-6.0 (5% sol) VAPOR DENSITY AUTOIGNITION NFPA RATINGS Health: 2 Flammability: 1 Reactivity: 1 REFRACTIVE INDEX FLASH POINT 190 C STABILITY Stable under ordinary conditions APPLICATIONS Cyanic acid (the isomer of fulminic acid) is an unstable (explosive), poisonous, volatile, clear liquid with the structure of H-O-C¡ÕN (the oxoacid formed from the pseudohalogen cyanide), which is readily converted to cyamelide and fulminic acid. There is another isomeric cyanic acid with the structure of H-N=C=O, called isocyanic acid. Cyanate group (and isocyanate group) can react with itself. Cyanuric acid (also called pyrolithic acid), white monoclinic crystal with the structure of [HOC(NCOH) 2N], is the trimer of cyanic acid. The trimer of isocyanic acid is called biuret. • Cyanic acid: H-N=C=O or H-O-C¡ÕN • Fulminic acid: (H-C=N-O) or H-C¡ÕN-O • Isocyanic acid: H-N=C=O • Cyanuric acid: HOC(NCOH) 2N • Biuret: (NH 2)CO) 2 NH Cyanic acid hydrolyses to ammonia and carbon dioxide in water. The salts and esters of cyanic acid are cyanates. -

Cyanogera Bromide and Cyanogen. by AUGUSTUSEDWARD DIXON and JOHNTAYLOR

View Article Online / Journal Homepage / Table of Contents for this issue 974 DIXON AND TAYLOR: GI.- Cyanogera Bromide and Cyanogen. By AUGUSTUSEDWARD DIXON and JOHNTAYLOR. CYANOGENbromide, in cold aqueous solution, or in the presence of such dilute acids as do not of themselves chemically decompose it, shows no evidence of suffering ionic dissociation. The dilute aqueous solution has the same odour as the solid compound; even after long keeping it yields with silver nitrate no turbidity; it is neutral to litmus, and the pungent vapour fails to give the guaiacum and copper sulphate reaction for hydrogen cyanide ; moreover, the solution is a very feeble conductor of electricity. Although the mixture produced by treating cyanogen bromide with alkali hydroxide contains but alkali bromide and alkali cyanate, Chattaway and Wadmore are of opinion (T., 1902, 81, 199) that hypobromite must first be formed, and then reduced. That cyanate is not directly formed in the reaction with alkali hydroxide is proved from the following facts: (1) Alkali cyanate is not reduced to cyanide by hydriodic acid, ferrous sulphate and alkali, sulphurous acid, alkali sulphite, or even by treatment with aluminium and alkali hydroxide. Further, it has no action on carbamide, either alone or in presence of alkali, (2) If cyanogen bromide is treated with alkali iodide, followed -by alkali, the mixture contains cyanide, but no cyanate, and, when acidified, yields free iodine. (3) If it is treated with ferrous sulphate, and subsequently with alkali and ferric salt, the mixture on acidification gives Prussian- blue, but contains no cyanate. Published on 01 January 1913. -

CSAT Top-Screen Questions OMB PRA # 1670-0007 Expires: 5/31/2011

CSAT Top-Screen Questions January 2009 Version 2.8 CSAT Top-Screen Questions OMB PRA # 1670-0007 Expires: 5/31/2011 Change Log .........................................................................................................3 CVI Authorizing Statements...............................................................................4 General ................................................................................................................6 Facility Description.................................................................................................................... 7 Facility Regulatory Mandates ................................................................................................... 7 EPA RMP Facility Identifier....................................................................................................... 9 Refinery Capacity....................................................................................................................... 9 Refinery Market Share ............................................................................................................. 10 Airport Fuels Supplier ............................................................................................................. 11 Military Installation Supplier................................................................................................... 11 Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Capacity................................................................................... 12 Liquefied Natural Gas Exclusion -

United States Patent Office 2,395,455

Patented Feb. 26, 1946 2,395,455 UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE 2,395,455 . DHYDRONoRPoLYCYCLOPENTADIENYL SOBOCYANATES Herman A. Bruson, Philadelphia, Pa., assignor to The Resinous Products & Chemical Company, Philadelphia, Pa., a corporation of Delaware No Drawing. Application January 13, 1945, Seria No. 57239 9 Claims (CL 260-454) This invention relates to addition-rearrange endomethylene group and possess two double. ment products of nascent thiocyanic acid (HSCN) bonds, only one of which, however, responds to and polycyclopentadienes having two double the reaction with thiocyanic acid even when in bonds and one to four endomethylene cycles per excess. Individual, relatively pure, polycyclo molecule. It further relates to a method for the 5 pentadienes may be used or mixtures of these preparation of these new products. hydrocarbons. In accordance with the disclosure of the pres The reaction of polycyclopentadienes and nas ent application, which is a continuation-in-part cent thiocyanic acid takes place particularly rap of application Serial No. 476,646, filed February idly in the presence of water-at temperatures 20, 1943, thiocyanic acid is reacted in the pres 0 of about 60° C. to about 110° C., although some ence of water with polycyclopentadienes having what lower and higher temperatures may be used. the formula: In the preferred temperature range little, if any, polymerization of thiocyanic acid occurs. This acid is generated in situ from a thiocyanate salt 5 and a strong, non-Oxidizing acid which is strong er than thiocyanic acid. The reaction between polycyclopentadiene and thiocyanic acid is carried out by mixing a salt of thiocyanic acid, water, and polycyclopentadi so ene, heating the mixture to a reacting tempera ture, preferably 60° C. -

Thiocyanatocobaltous Acid and Its Alkali Salts

ThiocyanatocobaltOKs Acid 15? THIOCYANATOCOBALTOUS ACID AND ITS ALKALI SALTS. F. J. Allen and A. R. Middleton, Purdue University. When an aqueous solution of K2Co(SCN)4, to which sufficient KSCN has been added to make the solution 0.8-1.0 normal in thiocyanate, is shaken with sufficient 1:4 ethyl alcohol-ether to form a separate layer, only traces of a blue compound pass into the ether layer. If the solution be now acidified with mineral acid, practically all the blue compound passes into the ether layer. As the blue color has been shown by Rosen- heim and Cohn' to be due to a bivalent complex negative ion, Co(SCN)4 " it appears probable that in the acid solution the free acid, H2Co(SCN)4, may be formed which is readily soluble in ether while its potassium salt is nearly insoluble. Two similar acids, H2Hg(SCN)," and HAu (SCN)4 .2H20,:j have been isolated in solid, crystalline form. Pre- liminary attempts to isolate the acid in solid form, by evaporation of the ether solution in an evacuated desiccator, showed that large amounts of HSCN were evolved as the solution concentrated. A mixture was deposited consisting of long slender needles of deep blue color which showed a strong acid reaction when moistened with water and short needles of a bluish green color. No method of separating the two suf- ficiently for analysis has been found up to this time. In order to obtain some information as to the nature of the ether-soluble blue compound, experiments were made to determine the partition of acid, thiocyanate and cobalt between the aqueous and ether layers at 25° C. -

-

New York City Department of Environmental Protection Community Right-To-Know: List of Hazardous Substances

New York City Department of Environmental Protection Community Right-to-Know: List of Hazardous Substances Updated: 12/2015 Definitions SARA = The federal Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (enacted in 1986). Title III of SARA, known as the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Act, sets requirements for hazardous chemicals, improves the public’s access to information on chemical hazards in their community, and establishes reporting responsibilities for facilities that store, use, and/or release hazardous chemicals. RQ = Reportable Quantity. An amount entered in this column indicates the substance may be reportable under §304 of SARA Title III. Amount is in pounds, a "K" represents 1,000 pounds. An asterisk following the Reporting Quantity (i.e. 5000*) will indicate that reporting of releases is not required if the diameter of the pieces of the solid metal released is equal to or exceeds 100 micrometers (0.004 inches). TPQ = Threshold Planning Quantity. An amount entered in this column reads in pounds and indicates the substance is an Extremely Hazardous Substance (EHS), and may require reporting under sections 302, 304 & 312 of SARA Title III. A TPQ with a slash (/) indicates a "split" TPQ. The number to the left of the slash is the substance's TPQ only if the substance is present in the form of a fine powder (particle size less than 100 microns), molten or in solution, or reacts with water (NFPA rating = 2, 3 or 4). The TPQ is 10,000 lb if the substance is present in other forms. A star (*) in the 313 column= The substance is reportable under §313 of SARA Title III. -

6 NYCRR Part

6 NYCRR PART 597 HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES IDENTIFICATION, RELEASE PROHIBITION, AND RELEASE REPORTING (Statutory authority: Environmental Conservation Law sections 1-0101, 3-0301, 3-0303, 17-0301, 17-0303, 17-0501, 17-1743, 37-0101 through 37-0107, and 40-0101 through 40-0121) TABLE OF CONTENTS 597.1 General. ....................................................................................................................2 597.2 Criteria for identifying a hazardous substance or acutely hazardous substance. .....5 597.3 List of hazardous substances. ...................................................................................6 597.4 Spills and Releases of hazardous substances. ..........................................................6 Table 1 Hazardous Substances – Sorted by Name ................................................................9 Table 2 Hazardous Substances – Sorted by CAS Number .................................................49 6 NYCRR Part 597 – Oct. 11, 2015 Page 1 of 88 597.1 597.1 General. (a) Purpose. The purpose of this Part is to: (1) set forth criteria for identifying a hazardous substance or acutely hazardous substance; (2) set forth a list of hazardous substances; (3) identify reportable quantities for the spill or release of hazardous substances; (4) prohibit the unauthorized release of hazardous substances; and (5) establish requirements for reporting of releases of hazardous substances. (b) Definitions. The following definitions apply to this Part: (1) Authorized means the possession of a valid license, permit, or certificate issued by an agency of the state of New York or the federal government, or an order issued by the Department or United States Environmental Protection Agency under applicable statutes, rules or regulations regarding the possession or release of hazardous substances or otherwise engaging in conduct which is exempt under applicable statutes, rules or regulations from the requirements of possessing such a license, permit, certificate or order.